Can dreams come true? They can if you win the lottery, which promises to provide what your heart desires. For a humble shopkeeper in Yiwu, it’s a living, selling lottery tickets. Until a winning ticket opens up mysteries he’d never imagined.

1.

In all his time working for the lottery, Eshamuddin had only ever sold three winning tickets but, as a consequence, he had seen three miraculous things.

The first purchaser, years before, was one of his first ever customers. She was a young, dark-haired girl with a look of intense concentration on her face as she handed over the cash money, and she retained one coin—a Martian shekel with the Golda Meir simulacrum’s head on– to scratch the card, which she did with a slow seesawing motion, gently blowing the cheap dust of silver foil as she searched for her luck.

Then her face changed. Not open disappointment, or stoic acceptance, of the sort that people always wore, nor the greedy desperation that meant they would ask for another ticket, and then another, until their money ran out.

But neither was it amazement, or shock, or any reaction of the sort he’d have expected were someone to get lucky. For someone to win.

It was more like she had found something that she had always half-suspected was there. That she was merely, at last, able to confirm a thing she’d always, instinctively, known.

And then she smiled.

And then she turned into a black-headed ibis and flew away into the sky.

2.

The second one was a couple of years later and it was a much more ordinary affair. The winner this time was a middle-aged man from Guangzhou, with a comb-over and bottle-top glasses and a nice smile; he had the sort of face that smiled easily, and sometimes ruefully, at the world’s foibles. It was the third card he’d bought and he was chatting to Esham all this while, a running commentary about the day’s weather (it was humid), the cost per unit of elastic hair bands (he had recently found a new manufacturer who could make them a point cheaper, saving him thousands), and his daughter’s new boyfriend (a no-good know-it-all, but what were you going to do? Kids today and all that). Then the silver foil all came off and the man’s face slackened and his lips stopped moving and he rocked in place as though he’d been struck, and Esham said, “Sir? Sir? Are you all right?” and the man just nodded, over and over, and finally gave him a goofy grin.

“Look,” he said. “Would you look at that.”

A car appeared ’round the corner and came to a stop beside Esham’s lottery stall. It was a long black limousine, with darkened windows. The doors opened and two men in dark suits and dark sunglasses stepped out. They both had short cropped hair and were very trim and fit. One held the door of the limousine open. The other said, “Congratulations, sir. Please, come with us.”

“But where are we going?” the man said.

“It’s only a short ride to the airport, sir.”

“The airport?”

“To get to the Singapore beanstalk, sir. It isn’t a long flight, sir.”

“Singapore? I have never been to Singapore.”

“It will only be a short stop, sir. A pod on the beanstalk is already reserved for you. Here, sir. Your ticket.”

“My ticket?”

“For your onward journey.”

The man stared at the ticket. He looked, almost pleadingly, at Eshamuddin.

“So it’s really true?” he said. “I won? I won the lottery?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I’ve always wanted to see Mars,” the man said. “Olympus Mons and Tong Yun City and the Valles Marineris kibbutzim…”

“Whatever your true heart’s desire, sir,” the man said. It was the same legend that was etched—in now dusty letters—above Esham’s lottery stall. The same legend that was on every lottery stall, anywhere. That was on every ticket.

Whatever your true heart’s desire.

“But my daughter, my job, I can’t just… elastic hair bands,” he said, desperately.

The car waited. Esham waited. The two men in their short cropped hair and smart black suits and ties waited. The man mopped his brow. “I suppose…” he said.

“Sir?”

He meekly let them lead him to the car. He folded into the cool interior and the doors shut and the two men disappeared inside and the car started up and drove away and the man was gone.

To Mars, Esham supposed.

“Mars!” said Mrs Li. She pushed her way to the booth and leered at Esham. “Who in their right mind would want to go to Mars, boy?” She shoved a handful of coins across the counter. “Give me a ticket.”

Esham took the money and gave her a ticket. You could count on Mrs Li to buy a few at a time. He wondered what her true heart’s desire was.

“That’s none of your damn business, boy!” Mrs Li said.

She scratched the card with maniacal glee.

3.

The third time he witnessed a miracle it wasn’t anything like that.

It was a foreigner, a trader on a purchasing trip to Yiwu from one of the coastal African states. He was with a couple of colleagues, and he bore an amused smile as he paid for the ticket. It was just something to do, a local custom, something to pass the time, he seemed to suggest. He scratched the card and looked at it with that same tolerant smile, and he began to say, in bad Mandarin, “What does this mean–” when it happened.

It was like a curtain swished behind the man. The man half-turned, looked, and there was an expression on his face that Esham couldn’t read. The man reached out one hand and touched the curtain. He prodded it with his fingers. He took a half step, and then another. There was nothing there, and yet there was. He half-turned back and smiled at Esham. Then he stepped through into the whatever-it-was and just… disappeared.

His two colleagues did a lot of shouting and Esham did a lot of hand waving and shouting back and finally some of the market police came along and they did a little shouting too and then, after a while, everyone left.

Esham stayed, of course. But business was slow and after another hour he closed the stall for the day. It had been a strange one. He wondered where the man went, and what he saw, and whether he was happy there.

He ate a bowl of crossing-the-bridge noodles at a Yunnanese stall, then had sweetened mint tea at a Lebanese café near the Zone 7 mosque, and then he walked slowly back. Two blind musicians played the guqin outside Pig Sty Alley, and the air was perfumed with wisteria. The smell was manufactured in the factories of Zone 10, at a very reasonable per unit cost, and consequently sold all across the world.

That night, Esham drew the walls of his stall-home down and sat inside. He tuned in to the latest episode of his favourite soap, Chains of Assembly, which broadcast across the hub network of the Conversation in near space, all the way from Mars. In the air before him, The Beautiful Maharani argued with Johnny Novum inside her domed palace, as ice meteorites fell onto the red sands far in the distance. Esham ate shaved ice with lychee syrup. It had been a strange day, he thought.

4.

Esham was born in Yiwu but he wasn’t Chinese. Many native-born residents of Yiwu weren’t. His father had been a small-goods trader from the Ecclesiastical Confederacy of Iran, and his mother was an interpreter for a mining company based in the Belt, which purchased mass-market goods for the asteroid longhouses. A space Dayak, she often complained of discomfort in Earth’s gravity, not because she was not used to it but because, unlike on the longhouses, there was simply no escaping it, even for a time. In the Up and Out, she’d told the young Esham, one could simply kick off into a free-fall zone, where you could fly: where you could be free.

He didn’t know what his mother’s true heart’s desire would have been. He remembered them both as loving parents—which is not to say they did not sometimes shout at him, in frustration, or that they did not fight, which they did—but when he thought of them, what he remembered first was love. His father was away a lot, a train man, as they called them, forever riding the rails along the Silk Road, from Yiwu to Tehran. He’d come back bearing gifts for Esham’s mother—saffron and dried apricots, tiny pickled cucumbers, rose water and golpar—and for Esham he’d bring back little hand-made curios, wood and wire intertwined with wildtech components, toys that existed in both the virtual and the real.

They died in a simple transport capsule accident on a visit to the underwater cities of Hainan. The new cities were the jewels of the South China Sea, glittering biospheres abundant in offshore aquaculture, home to millions of people who lived and breathed under water. It was just a stupid accident, the sort that never even made the news. He was still only a boy when it happened. After that the state took him in. For a long time he’d had the dream of buying lottery tickets until he’d found a winning one and then the lottery would bring his parents back to life. Even though he knew it was just a dream. Even the lottery could not bring back the dead.

The lottery really began as just another roadside tradition, around the time they rebuilt Yiwu from scratch into the lotus flower shape it had now. Each petal a zone, each zone a market to rival all other markets. There was nothing, it was said, that you couldn’t buy in Yiwu. But mostly it was the small stuff, the domestic stuff, still, then and now: key rings and bath mats, mugs and toothbrushes, artificial flowers, ladies’ handbags, raincoats and mascaras, pens and watches, clocks and toys and festive decorations… the factories in the outer zones beyond the city never slept, the market traders in their petal-sections of the market-city only ever slept in shifts, and the trains never stopped coming and going with the giant containers on their backs.

The first lottery was on the same scale. It really was just a community sort of thing. People coming together to make your life a little easier, a little better. When people would get together and buy tickets and each would win something they needed—help with repairs on their house, or delivery assistance for groceries, or someone to bring you food while you were sick, if you didn’t have family to care for you.

At least, that was the story.

On how the lottery really came to be, there were as many stories as there were fish in the fish market or toys in the toy market or pens in the pen stalls or fake snow in the Christmas pavilion. They said the lottery used Shenzhen ghost market tech and was overseen by the Others, those mysterious digital intelligences that first evolved in Jerusalem’s Breeding Grounds and now lived in impenetrable Cores guarded over by the mercenaries of Clan Ayodhya. Others said it was run by the Kunming Toads under Boss Gui, whose labs in the Golden Triangle churned out verboten technology and traded in illicit info-weapons and employed Strigoi assassins for all that they were banned on Earth. Others still said it was wild hagiratech from Jettisoned, that farthest outpost of humanity on the moon called Charon, from where the sun appeared as little more than a baleful raven’s eye in the sky, and that the lottery was run from off-world, and you know what people in the Up and Out were like.

Esham didn’t know. He didn’t even think to ask. The lottery just was, and it gave a few people every year something impossible and precious: their true heart’s desire. And it gave him, Esham, a job.

5.

Every morning he sat up in his cot and brushed his teeth in the sink and washed his face and his armpits and he drank a cup of tea. Then he unfolded the walls of the lottery booth and prepared to welcome the day. If the previous day’s take was good, he might walk to a nearby stall for a bowl of congee. If the take was not good, he would usually forego breakfast. His accommodation was free and his needs were few, and only the rich, as the old proverb goes, have time to dream. But that’s what the lottery was for, he thought. For the poor to have dreams.

From time to time he would move the lottery stall around the city. There were many lottery stalls but they all travelled if they needed to. Currently he was stationed in Zone 7, where the automata market was. Every late afternoon he’d shut the booth for an hour or so and take a stroll. The petal of Zone 7 rose high into the air above the central pistil. From up here you could look all over the city, to the zone-petals and their markets heaving with humanity and goods, and to the mountains that ranged Yiwu, and to the outer zones where the workers lived in the vast container shanties and grew their hydroponics food in green growtainers, and then beyond to the ring of factories. The petals were designed to catch wind and sun and rain, to reuse everything, to draw power from the elements. If the previous day’s take was good he might buy himself a modest lunch of some sort: Vietnamese banh mi or pho, or an Egyptian falafel or a bowl of noodles. If the take was good he might go to the public baths to wash. While the city operated on a range of digital currencies in the Conversation, the lottery only ever accepted coins. Why that was he didn’t know. They did not mind the type of currency, so each day Esham would sort out the day’s take by type and place of origin: Martian shekels and rubles alongside Belt-issued ringgit, local yuan, Micronesian dollars, lunar vatu… the list went on and on. Each evening he would pack the coins and place them in the appropriate bin provided, and each morning they would be gone.

Esham had his regulars. Mrs Li, who owned a factory that made snow globes, visited him every day. Mr Mansur, who came each year to Yiwu to buy lights, so many lights that he shipped to his distant home, would visit avidly when he was in town. He could always be relied upon to buy the extra ticket, and his face always bore a hopeful, yet simultaneously sad, look. He was a quiet, courteous man. There were others. They came and went like the tides.

In the afternoon a troupe of Martian Re-Born walked past, red-skinned, four-armed, laughing, wearing lanyards with laminated cards on their chests. They were of an Up and Out order which believed in an ancient Martian civilization ruled over by an Emperor of Time, and they modified their bodies to match their imagined perspective of that long vanished warrior race. They stopped, curious, at his stall and each bought one ticket, and they paid with coins that bore the profile of a P’rin, those imaginary reptilian birds that the Re-Born believed were the time-travelling messengers of their Emperor. None of them won.

A street cleaning machine crept past along the road, humming cheerfully to itself. Trams whooshed overhead on their graceful spirals, moving between the zones. The air smelled of hot leather, shoe polish, fried garlic, knockoff Chanel No. 5 perfume, uncollected garbage, frangipani and the recycled air blown out of a thousand air conditioners. It was then that he saw her, emerging from the market doors out into the hot street beyond.

The woman was no taller than Esham, but she moved with a quiet purpose that he envied: a sense of completeness, a comfort in one’s own skin he had never possessed. Esham was the sort of person who skulked through life, careful to avoid any potential for trouble. He had few friends and fewer vices and he never played the lottery.

The woman crossed the road and came to his stall and stopped. The laminated card attached to her lanyard said her name was Ms Qiu.

“Hello,” she said. The smile she offered him would have broken his heart had he opened his heart to it.

“Hello,” he said.

She had just an ordinary face, the sort you would easily lose in a crowd. Her hair was cut in a fashionable style that was nevertheless a year or so behind whatever the current trend was in Shanghai that spring. Her hand rested on the counter, lightly. Her fingers tapped on the surface. He looked away from her.

“May I have a card?” she said.

“Of course.”

She smiled when he gave it to her. She scratched it with an old 50-mongo coin. She looked at it, almost puzzled, then shrugged and left it on the counter.

“Thank you,” she said.

“You’re welcome.”

He watched her walk away.

6.

This became a daily routine. He came to await the moment when Ms Qiu appeared out of the market entrance. He’d watch her cross the road. He’d always wait. She’d say, “Hello.” He’d say, “Hello.” She’d ask for a card, and he would pass one to her, and she’d pay him with whatever coins she happened to carry that day—rubles, dinars, one time with a gold sovereign. Then she’d frown, shrug, give him a final smile or say, “Goodbye,” quietly, and walk away.

Sometimes, on his break, he would search for her in the market. He’d pass the rows of artificial cockatoos and peacocks, and the little singing birds in their cages with their bright glass eyes, and the enclosure of the animatronics tigers and the dodo arcade, but only once he thought he saw her, at a distance, speaking to a man in a navy-blue suit, but he could not be sure and, when he came closer, she was gone, if it had been her at all.

He took to eating his lunch at a Melanesian stall serving sup blong buluk wetem raes, simple, filling fare, and cheaply priced, a place popular with many of the Pacific traders. It was across the aisle from a stall that sold genuine synthetic bears’ gall bladder, and the girl who worked at that stall would often take her lunch around the same time.

“Don’t you remember me?” she said. “Isa, from the home.”

“Isa,” Esham said. “Of course. Of course.”

“I’ve seen you around,” she said. “So you went with the lottery.”

“I did. You?”

“Well, you can see.”

“Artificial gall bladders.”

“I have my own place now,” she said. “It’s in container town but I’m there alone, no one else.”

He knew what she meant. Growing up the way they did they were never alone, there were always others, nights filled with snores and farts and someone crying or talking in their sleep.

“Me, too,” he said. “It isn’t much but…”

She smiled.

“I know.”

She sat down across from him, with her tray. “You ever think of going away?” she said. “Mars, or the moon, or Beijing?”

He thought about it.

“No,” he said.

She nodded. “Me neither.”

She spooned beef stew over the rice and ate, wasting nothing, and he did the same.

7.

The way it happened wasn’t supposed to happen. There was something wrong, in hindsight, with the whole day, some intimation of disaster one could trace in the slight rise in air pressure or in the swoosh of the trams overhead, or in the clinking of coinage. Mrs Li came and bought three tickets, and left with a huff. Mr Mansur came by and bought one, and stopped to chat for a little while before he, too, left. A couple of monks went past and did not buy tickets. A bulk buyer from the Martian Soviet came and got a ticket and then a trader from Harbin.

It was just an ordinary day, the way Esham liked it. Order and routine, a knowing of what was expected. At the usual time, Ms Qiu emerged from the market doors. She crossed the road. She came to the stand and smiled at him and said, “Hello,” and asked for a ticket.

He sold her one. She scratched the silver foil with a 10-baht coin.

She looked at the card, almost puzzled, then shrugged and left it on the counter.

“No luck?” Esham said.

She pushed the ticket towards him. He glanced down, barely registering the impossible at first: the three identical symbols of a beckoning gold cat that meant it was a winning ticket.

He glanced up at Ms Qiu.

Nothing happened.

“Thank you,” Ms Qiu said.

She gave him a last, almost bemused smile, then turned and walked away.

Still nothing happened.

He stared at the good luck cats.

Nothing.

Ms Qiu crossed the road and walked away the way she always did, until she turned a corner and was out of sight.

Still nothing happened.

They said when old Mr Chow won, it had rained fish all that day, all over the city.

They said that when Mrs Kim won, statues came to life and danced for a full five minutes to a K-pop song before they suddenly and abruptly became stone again.

They said when Mr Huang won, a dragon flew over the city, and summer flowers bloomed, and when young Miss Yuen won, she vanished and reappeared in digital form as a speaking part character on Chains of Assembly, where she had a brief but intense romance with Johnny Novum before falling afoul of Count Victor’s machinations against the Beautiful Maharani, after which she was not seen again on the programme.

Esham stared after Ms Qiu, but nothing happened. He held the winning ticket, stared at it. Something was wrong, he thought. It wasn’t supposed to happen like this.

Rain clouds gathered over the flower-city of Yiwu.

He stared up at the sky, but they were just ordinary rain clouds.

8.

“Area Controller Dee will be with you shortly. Please wait.”

Lottery sub-level 15 was a mix of physical reality and the virtual. Disembodied daemons moved through the air whispering machine language instructions while forklifts drifted across the factory space moving heavy bags of coinage, and in the far end the printing presses thumped and hummed, churning out sheets and sheets of promised miracles which were then chopped neatly by other machines and sorted for delivery to the various stalls. In many ways it could have been the quintessential Yiwu market floor, small scale manufacturing, large scale distribution, only here they didn’t sell bath mats or doorknobs, they sold miracles.

He wondered what they did with all the coins.

“Only, how long will it be?” he said. “This is very important.”

“Please wait. Area Controller Dee will be with you shortly.”

Esham touched the bruise on his cheek.

There had been trouble the night before.

He’d been careless, a customer came past shortly after and they saw he held a winning ticket. He’d tried to explain but he didn’t know how.

Word spread.

The rumour went around that there was a winning ticket up for grabs. Even though everyone knew the lottery didn’t work that way.

They came to gawk at his lottery stand, only a few at first, then more, until it was more like a mob that surrounded him. Night fell and the air had a wild, festive feel to it, but mixed with a sense of unpredictability. People lit torches and drank beer and baiju. Fights broke out. People kept shouting questions at him. He couldn’t leave. Then a group of young men set on him. They demanded to see the ticket. He tried to shut the booth but they started pushing it, rocking it from side to side. Esham tried to slip out and someone pushed him, and he fell. The mood turned ugly. He looked up and saw their faces, lit and hungry. He curled up into a ball. He’d been kicked before, the key was to try and minimise the damage.

They started landing blows. Fists, feet. Then someone shouted, “Leave him alone!”

It was Isa, from the market. She came in, fearless, and stood over him and faced down the bullies.

“Go away,” she told them.

Which, remarkably, they did.

She helped him to his feet.

“Are you all right?”

He tried to smile, though it hurt.

“Here,” she said. “You’re bleeding.” She sat him down on a bench and cleaned the cut in his face. His ribs hurt from the kicking. The city shone overhead in a million lights.

“Thanks, Isa.”

“We’ve got to look after each other,” she said. “Or who else will?”

He nodded. He felt very tired.

They sat together on the warm bench under the petal zones of the city, side by side, in companionable silence.

9.

“I must speak to the Area Controller,” Esham said. It had taken him hours to find the lottery regional office. It really was just a door, tucked in the back of Zone 2, and he’d had to pass through miles of near-identical corridors, through stalls which sold miniature models of folding Beijings, fish from Lijiang and flowers from Shazui, Perky Pat dolls bound for Mars and replica guns from Isher, anti-spiritual pollution spray in aluminum cans, Samsara wheels that played a song as they were spun and little self-assembly spacecraft models from General Products—a sea of kipple, an endless, rolling expanse, heap upon heap of old stuff someone, somewhere, simply couldn’t let go of.

He went past it. He found the door. It was just a door.

“I must speak to the Area Controller,” he said.

The door seemed to hesitate.

“This is most irregular,” it said.

“The situation is most irregular!” Esham said, with more force than he meant to.

“I’m sorry,” he said.

“Don’t mention it,” said the door.

“Can I come through?”

The door hesitated.

“We’re very busy right now,” it said.

“This is important!”

“I am sure,” the door said, in a maddeningly reasonable voice, “that is seems very important to you.” It sighed. “I wasn’t always a door, you know,” it said. “I used to be a poet.” It reflected for a while. “Still. I like being a door. Sometimes you’re open. Sometimes you’re closed. There’s very little in between. I find that comforting. Don’t you?”

“Me?”

“Well, you’re not a door,” the door said. “So I suppose you wouldn’t understand.”

It seemed to reflect again.

“Oh, well,” it said at last. “But don’t say I didn’t warn you.”

The door irised open.

Esham stepped through.

10.

The corridor felt like an access tube strung over some enormous height. The accordion walls contracted and expanded and the whole passage seemed to move as though buffeted by unseen wind. He stumbled along it, holding on to the walls to stay upright. Lights flashed overhead. A mechanical voice kept counting, “Eight billion point two four five, eight billion point two four seven, eight billion point two five one,” incomprehensively. Esham came to the end of the corridor. He stepped through…

For a moment he had the sense of galactic space all around him. He saw a planet adorned with rings, and fireflies in formation all around it, and the sun far against the endless dark, a lone yellow star. Then it vanished and the voice stopped the count and a new voice said, “Welcome to Lottery sub-level 15, vendor human type Eshamuddin. Area Controller Dee will be with you shortly.”

He looked around him, at this ordinary floor. It could have been any market level in Yiwu. Though he was suddenly certain he was nowhere near Yiwu. Not even on Earth, maybe. There were windows in the far walls. He could see a night sky, but not much else. Height, though. He was high up, in a skyscraper, somewhere foreign. He was almost sure. He began to walk to the windows. If only he could see…

“Sir? Come with me, please.”

11.

Area Controller Dee was a short, fat man in a chequered shirt with one button too many undone and thinning black hair that stuck to his forehead. He mopped his face and pushed the basket of food on his desk towards Esham.

“Prawns?”

Grease shone on his fingers. Esham shook his head.

“No. Thank you.”

“Suit yourself.”

Dee ate fast. When he finished he let out a satisfied burp and wiped his fingers clean on a dirty napkin.

“So,” he said. “What is all this about?”

“Sir,” Esham said. “Do you mind if I ask where we are?”

“The lottery building,” Area Controller Dee said.

“But where, I mean what–”

“The lottery is the lottery,” Area Controller Dee said. “Yes?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Now, could you get to the point? I don’t have all day.”

“It’s about this ticket, sir. It’s a winning ticket, sir.”

“A winning ticket? Let me see.”

Dee took the scratch card from him. He looked at it and pursed his lips. His eyes glazed, for a moment, as he accessed his node.

“Ah, yes,” he said. “Defunct.”

“Defunct, sir?”

“It was an error,” Dee said. “Don’t worry about it.”

“So it didn’t work? But Ms Qiu–”

“Ms Qiu?” Dee said.

“The woman who purchased it, sir.”

“Not human,” Dee said.

“Not human, sir?”

“Automaton. Replica. Animatroni– well, you know.” He waved his hand. “Ex-display.”

“Ex-display?”

“Do you just repeat everything anyone ever says to you?” Dee said.

“Yes, sir. I mean, no, sir. Sir, what do we do here? What is the lottery for?”

Area Controller Dee unwrapped a lollypop and stuck it in his mouth. He sucked on it noisily then took it out with a pop.

“The lottery’s the lottery,” he said, with an air of satisfied finality.

12.

Arrows led him back the way he’d come across the floor. Far in the distance he saw an old mechanical slat board that kept clacking, with figures that kept changing for Mars, Lunar Port, Titan, Ganymede, Io, Calisto, Jettisoned, Ceres, Vesta, Calypso, Hyperion, Nix and Hydra. And Earth, of course. The same mechanical voice returned, “eight billion point two six eight, eight billion point two seven one,” droning on. Esham came to a door. He opened it, and stepped out onto a street in Yiwu.

It was late afternoon. The sun was low against the mountains. The petals of the market zones rose in the sky, casting shadows over the surface streets. He was in a quiet residential neighbourhood not far from Zone 7. As he stood there, he saw Ms Qiu cross the street. She walked in that same assured, unhurried pace. She didn’t see him. She came to a small house with a well-tended front garden and a little white fence. Two children came running out to greet her, and Esham thought he saw the outline of a man waiting at the door. Ms Qiu went in with the children.

Esham came a little closer. He peeked through the windows, which were open to let in the breeze. He saw them sit down at the dinner table, the children talking animatedly, Ms Qiu smiling quietly. The man said something and she laughed.

Esham left them to have their privacy. He walked back to his stall, and saw that Isa was there, waiting for him.

“I thought I’d take you out to dinner,” she said.

“I’d like that,” Esham said.

“What shall we have?” she said. She laughed. “Whatever is your true heart’s desire.”

So they shared crossing-the-bridge noodles at the Yunnanese stall, and then they had sweetened mint tea at the Lebanese café.

And then, together, they went home.

Text copyright © 2018 by Lavie Tidhar

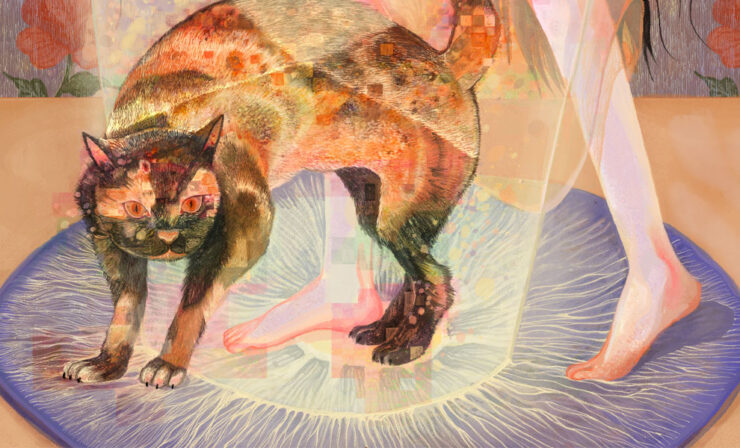

Art copyright © 2018 by Feifei Ruan

Buy the Book

Yiwu