“You’re using me,” I said.

“That might be true, but I also love you.”

One is the Lady of the Waking Waters, an immortal mermaid. The other is a thief, who steals lives until a wish can be fulfilled, and a life-changing choice must be made.

I only led the worst of men down to the Waking Waters and death, down to my love in the pool below the falls. I only led the foul men with filth on their tongues, the rich men who contrived to rule other men. I only led the men with hatred in their hearts and iron in their hands. I spurred them on with tales of hidden silver or the sight of my girlish thigh, down out from the mountain town of Scilla, down to the hills and the pines and the ruttish perfume of wildflowers.

All so that the Lady of the Waters might love me.

Well, that and so I could rob their corpses.

The morning sun sat low in the western sky, and the streets were empty near the edge of town. The man with me that day was handsome. He was twenty-five years my senior, with three teeth of silver, a gold-hilted sword and dagger, and a string of badges he’d won by gambling his life for the King’s glory in a foreign land. A town like Scilla saw men like him only once a year, only for the night market.

He’d found me walking with a basket of flowers. I caught his eye and smiled him over and yet he seemed to think he was the one propositioning me.

For a moment, I considered laying with him anyways, without taking part in his death, maybe just taking a few of his things while he slept. For all his pomp and arrogance, I liked the shape of his jaw and the fervor in his eyes.

We walked arm in arm away from the market, the daisies under my arm.

“And you swear you’re not a working girl?”

There was no good answer to a question like that. The answer was no: I don’t exchange labor for coin, I murder and rob. Of course I couldn’t tell him that, nor could I in good conscience distance myself from those among my friends who work more honestly.

I giggled instead. Men seem to like when I giggle at them. I don’t understand how they don’t see through it.

He jangled his full purse, laughing his horrid laugh. “Too many people think only about coin.” As if it would be strange for those of us without to be concerned about acquiring what we need to feed ourselves, clothe ourselves, house ourselves. “It’s weakness, pure and simple, and what people don’t understand is that weakness is our enemy. We must kill the weakest parts of ourselves as surely as we put down our weakest foes before they gather strength.”

He must have done terrible things to win awards like those pinned to his chest. If I focused on that, I could excuse the terrible things I planned to do.

“I know a better place than your room at the inn,” I said.

“If you’re not a working girl, there’s no shame to be seen with you.”

“I know a place, a better place, where the wind runs cool off the water. Where I can rinse, where you can rinse, where we’d taste our best for one another while only the deer of the forest look on.”

“You’ve done this before,” he said. He was hungry at my words, at the thought of watching me bathe.

I had. Twice before. He would be my third.

“So have you,” I said.

“What do I call you?” he asked.

“Laria.”

“A harlot’s name.”

“Fitting, then,” I said, starting out for the edge of town with him in my wake. I didn’t ask his name, because I didn’t care to know it and because no one would ever call him it or anything else again.

He followed me along the long road that wound down from Scilla. I promised him it wasn’t far, and I wasn’t lying. We skirted off from the road into the pines and followed the sound of the water. We went downhill and downhill, to the tall and tranquil Waking Waters falls, then downhill to the pool at their base.

There are more impressive waterfalls in this world, but the Waking Waters has a beauty of the sort that has no need to be spectacular. On midsummer evenings, like that one, the sun sets behind the top of the falls and makes it glow while the shadows turn darker everywhere else.

My quarry’s eyes flit across the woods around us, as though suddenly aware I might be leading him to ambush, but he was looking in the wrong place.

“After you,” he said, gesturing at the water. He didn’t trust me. He was a terrible man, but not an entirely stupid one.

I slipped off my shift with a smile, first at the man and then at the world around me. Wind carried a bit of mist and the scents of summer off of the water, and I strode toward and into the pool.

With each step, the water lapped at my skin. With each step, the water washed away the filth of poverty and the filth of the town and the filth of work–honest work, illicit work, it’s all work.

He watched me, of course. I would have watched me too. I was beautiful.

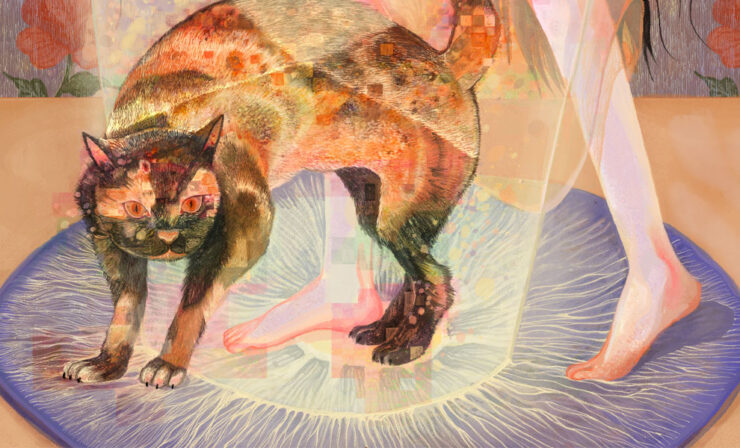

The Lady found me when I was waist-deep, running her human hand along my thigh. I dove. She swam alongside me, pressing her body to mine, with her bare breasts and her fish-tail.

We kissed, there, underwater, and I ran my tongue along her sharp fish teeth until just a drop of blood found its way into her mouth. I liked to tease her. I liked when she was hungry.

We emerged. The man on the bank, now stripped down to muscle, watched with wide, incredulous eyes.

“The Lady of the Waking Waters,” I said, by way of introduction.

I needn’t say more. I’d never needed say more.

She’s never told me a more proper name. I call her the Lady because I must call her something. For her own purposes, she has no need of a name.

A mermaid has her own magic, stronger than that of any creature born with legs, and even though she smiled and her teeth were white, thin razors, her eyes were bright and hazel. Her hair changed color as the sun, the wind, and the mist played off of it. Her skin was a perfect medium-brown. She could enchant any man alive.

He walked into the water, willingly, and I stepped out onto land.

He didn’t scream, because she removed most of his throat in the first bite. The rust-red, blood-red water slipped away over the rocks to feed the forest.

It’s always beautiful to watch someone perform their life’s work. The man we’d murdered, perhaps he’d been beautiful at war. He might have been beautiful on top of me, inside me. But the Lady, she was beautiful as she stripped flesh from bone.

Only the worst of men. I had honor as a thief, so damned if I wouldn’t have honor as a murderer.

I went to his belt, found his purse, and took those coins he’d rattled. The sun was hot on me as I worked my way through his clothes, unraveling the gold wire woven into his hems, unraveling the gold wire he’d wrapped around the hilt of his dagger to announce his wealth. I’d have to find someone to melt down the medals.

At last, I turned my attention from my work and back to the pool. The Lady was sunbathing on the rocks on the far side, and the water ran clear once more. She smiled, and I strode back into the water, back out to the Lady, my lover.

I put my mouth on hers, and she was gentle with me, kinder than anyone with two legs had ever been. When a mermaid’s lips are against your skin, time slows. The white noise of the waterfall became a low and quiet roar and I saw every sweet drop of water as it cascaded down the mountainside.

She pleased me with her hands and mouth while my feet dangled in the cold pool, and she had me breathing fast and easy, fast and hard, fast and easy, fast and hard, while the world crawled by around me.

For a moment, with the last of the sun on me, I had coin enough, and I had love enough.

“Can I just stay here with you?” I asked. The moon had risen, a crescent scythe in the field of stars. I hadn’t told her of my plans. In truth, I was afraid she’d dissuade me.

She was in the water to her neck, and I laid on my side on a rock with my face near hers. The roar of the waterfall cut out the sounds of the night, yet I could hear my heart hammering in my chest.

“Of course not,” she said. “I live in the water, and it would be the death of you by drowning to join me.”

“I don’t care if it kills me,” I said, weeping.

“I do,” she said. “I want you to still bring me men every few years when your hair has gone white and your skin hangs loose on your frame.”

“You only want to see me every few years,” I said.

“We’re not the same,” she told me. “It’s not possible for us to lead the same life.”

“What if it was possible, though? What if I changed? What if I found magic enough?”

“I love you as you are, Laria,” the Lady said. She brushed the wet hair, plastered to my face, away from my eyes. “I love the way things are between us.” She was sad, and smiling.

“You’re using me,” I said.

“That might be true, but I also love you.”

The world was blurry, through the haze of my tears. She kissed my cheeks, awkwardly, like a boy just learning what romance tastes like. Time slowed again, and I realized no matter how fast she’d killed that man with her teeth, he’d had all the time in the world to experience death.

I envied him, a short moment, for losing his life to the Lady’s teeth. Why are death and love and sex and change all tied up together in our heads?

But as her fingers ran down my neck, I grew calm. I was as happy as I ever was. She climbed out of the water, her tail transformed to legs. I laid on my bare back, and she straddled my hips, and we let time run slow once more.

The night was full-dark, with clouds obscuring the moon, when I made it back to Scilla. The sun had gone to rest, but the town had not. Vendors from all over the island were setting up under eaves and on the cobbles. Fifty weeks a year, my home was a dry husk of a town. Two, it drew the finest wares and wanderers in the country.

There was good work to be had at the night market. All kinds of work, legal and not. But with the weight of gold in my purse, I had no need. I wasn’t there for work. I was there for the witch.

A heavily-scarred cheesemonger cut into a wheel of something pungent and rich, and my stomach informed me I hadn’t eaten since the sun was at its peak.

“He’s sleeping off wine, that’s what I figure,” I heard. Next to the cheesemonger, two men-at-arms sat on a bench eating fried lamb, their polearms resting in the nooks of their arms. They spoke in the way of men who aren’t used to manners, of men who don’t care who hears them.

“The King’s Fifty are not the sort to abandon their posts,” the other man said, his voice full of gravel.

I’d killed one of the King’s Fifty. Pride and terror fought for control of my emotions.

“He’s probably fucking or drunk or just fucking drunk,” the first man laughed. “He’ll get here.”

I hurried away into the crowd, lest they somehow see the heft of my purse and the medals within. I had to be careful. There likely wasn’t a moneychanger disreputable enough to trust with my gold, not even the wire. As rumors raced through the market–a knight has been slain–my caution escalated to fear, and the physical sensation coursed through my body.

If I couldn’t trust a moneychanger, then better to trust the witch.

I found her tent set between a child selling counterfeit treasure maps and a cooper as old as the moon. Such was the night market.

Henrietta the Haggard, people call her, though it said Henrietta the Honored on the tapestry hanging on the side of her tent. I couldn’t read it, but once I saw a gentry-girl read it aloud to her father. I used to think it was funny, how Henrietta the Haggard had the wrong name written on her tent. Now it’s not so funny. I know what it’s like to need to advertise to the world what you are, so that people don’t just assume you are what they think you are.

“I have the coin to pay you,” I told Henrietta.

The thick canvas walls blocked the light from the street, and only the red ember glow from a dying brazier lit either of us at all. Thick incense, of a scent too exotic to place, tickled my nose.

Weary lines were etched into the witch’s dry skin, and she looked as old as the town, as old as the kingdom. Henrietta had as much magic as anyone on the island; she could look however she wanted. She chose to look decrepit. I liked that about her.

“You wish to become a creature of the lakes and rivers and the sea?” she asked.

I nodded.

Henrietta frowned. “Better to just let me read your palm and go.”

I pulled the coins and the coiled gold wire out from my purse and placed them on the counter. They gleamed, even in the scarce light of the embers.

“A spell like that would leave me drained a fortnight, at least. I’d lose all my other work. That’s quite a wealth of gold you have, child, and it could buy most anything in the market. It cannot buy Henrietta for a fortnight.”

I nodded. I’d expected that. I went back into my bag and pulled out the medals.

Her eyes grew wild, with surprise, greed, or suspicion.

“Tell me more specifically,” she said. “What do you desire to become?”

“A mermaid.”

“I can give you the tail of a fish and gills on your throat. I can point your teeth and give you a gullet built for blood. I will not work the dark magic required to make you immortal. I can’t grant you magic of your own, and you won’t be able to shift your tail to legs to move on land. You will be a creature of the water, and of the water only.”

I’d figured that was likely.

“Tell me, child,” Henrietta said, “have you been talking to the Lady of the Waking Waters?”

I thought no one knew of her but me. If Henrietta recognized the medals, she would know what happened to the soldier. She’d know my culpability in his death, sure, I’d counted on that–but she’d know the Lady’s involvement as well.

“Breathe, child,” Henrietta said. “Your eyes are wide and wild with guilt and it won’t do to be seen that way. I’m in the business of revealing the truth of the future and the past, but I’m not in the business of informing on my customers.”

She stood up–an imposing figure, like a stooped giantess–and went to close the flap of her tent. No light, no sound, came in through that canvas. The incense seemed thicker, the air hazier.

“Why?” she asked.

“Does it matter?”

“Yes.”

It took me a moment to collect my thoughts. “Because I’m in love,” I said.

“Is that a reason to give up your life on land and your body?”

“What life?” I asked. “Selling flowers for copper? Risking everything, constantly, to steal gold? This is the third town I’ve lived in in five years.”

“How will you run from your troubles, without legs?”

“I’ll have the whole of the ocean!”

“All right,” Henrietta said. “Stand up then, let’s have a look at you.”

I stood.

“You’re a boy under all of that?” she asked. There was no judgment in her voice. Ever since I’d taken a woman’s name and worn women’s clothes, people quickly sorted themselves into three categories: those who wanted to fuck me, those who were repulsed by me, and those who simply didn’t care. Henrietta didn’t care.

“More or less,” I said. It was hard to think of myself as a boy at all.

“Won’t matter soon enough,” she said. “Soon enough you’ll be a fish. Come on then, let’s get down to the water. I know a cove that should work.”

“Right now?” I asked.

“You sounded like you were sure before.”

“Shouldn’t we wait until tomorrow? So I can, I don’t know, get my affairs in order?”

“I thought there was nothing for you on land?”

Nothing suddenly felt like an exaggeration. There was Nettle and Fitch, the two girls I shared a room with in the loft over the stables. Would they be able to make copper enough for the landlord without me? And Fitch, the way she looked at me. I was in love with the Lady, that was as certain as the sun, but I liked the way Fitch looked at me too.

“I’ll meet you down there,” I said. “Give me, I don’t know, an hour.”

“I will cast the spell as the first light of dawn breaks over the water.”

I started to collect my gold from the table.

“Leave that here,” Henrietta said.

“What?”

“Leave that here so I know you’re serious, so I know this isn’t a prank, a waste of Henrietta the Honored’s time. I will destroy some not-inexpensive things in preparation for this working, and I won’t be cheated.”

“Where’s the cove?” I asked.

“Where the Waking Water feeds into the ocean. Don’t be late, child. A spell works on its schedule, not yours. If I prepare the spell, it will be cast at dawn regardless of what any of us desire.”

I nodded, and stood. The incense had me dizzy, and I stumbled out of the tent, back into the noise of crowded humanity.

At least a dozen men-at-arms crowded together near the front gate, strapping on coat-of-plates and brigandine. Each of the men towered over me, and the heads of halberds and pikes towered over them in turn. I shied back. Menace was in the air, and my head was still fogged with the incense and magic from Henrietta’s tent.

“Saw him leave with a girl,” one man, a hostler in town for the market, said.

I flipped up my hood, hiding my feminine hair, and took a half step back into the gathered and gathering crowd.

“You tell me when they left, how tall this girl was, and I’ll track Holann down sure as your mother’s milk.” The man who said that was a gray-haired old ranger, stocky and short with a glint of malice in his remaining eye.

Holann. The man I killed had been named Holann. Didn’t matter.

“What,” another soldier asked, “so we can catch him with another whore in the woods? Just let him sleep it off, we’ll see him in the morning.”

“You ever known him to abandon his post?” the ranger asked.

They argued for a while after that. The crowd lost interest and dispersed, and I found the shadow of a glassblower’s stall to hide in.

They were going to find the Lady.

They would follow my tracks down the hills and through the trees and to the water, and they would find the Lady, and all the magic she could bring to bear wouldn’t be enough to stop a company of the King’s own men. Not if she didn’t know they were coming.

Henrietta could wait. My transformation could wait. I ran.

If I’d had time, I could have misled the tracker. I’m not sure how. I could have thought of something. There wasn’t time.

I walked out of the town gate, through the crowd of arrivals, with my hood still obscuring my face. I made it to the tree line, stepped through, and went back to running.

There was no direct path, just a series of gullies and deer trails, and darkness obscured the forest. I didn’t get lost. I’d gone that way a hundred times. I skinned my knee, deep, on the rocks when I slipped near the end, but I scarcely registered the pain. My love was in danger.

I stumbled out of the trees and waded into the pool at the base of the falls. I would have shouted her name, had she a name, had I not been afraid of calling attention to our location.

The night had grown cold, and the water sapped at my strength if not my resolve. I plunged through the falls and into the alcove behind. Phosphorescent moss cast faint light that glistened on wet stone.

I saw her sleeping on the shelf, with legs. It was so easy to imagine she slept with legs because she wanted to sleep next to me. It was so easy to imagine that land was her first home, that water was simply another realm she could travel within.

It wasn’t fair, that she could walk and swim and I had to choose forever between one or the other. It wasn’t fair that I should be the one who would sacrifice for us to be together, when it would be so much easier for her.

She was beautiful. In the usual ways, yes, but she was also beautiful in the ways that anyone might become, when you get to know the secret language of their body and their lives. She’d been alive so long, seen so much, developed so much beauty. The longer I might know her, the more of her hidden beauty I might unearth.

“My Lady,” I whispered. I couldn’t hear my own words over the roar of the water.

“My Lady!” I shouted.

She woke, twitching, thrashing like a fish, and for a moment she wasn’t human. She was never human.

“You’re back,” she said, as she came to her senses. “So soon.”

“They’re coming,” I said.

“Prey?”

“Too many,” I said. “Men-at-arms. Friends of the man you…we…killed.”

She nodded.

A crueler person–maybe any human–would have blamed me.

“Have you come to die for me? With me?” she asked. There was no fear in her voice, nor even grim determination. She asked it like she might ask my thoughts on the weather. No, she asked it like she asked before she kissed me, before she touched me. She was asking for my consent.

For a moment, I wanted to die alongside her as fiercely as I wanted to kiss her. My life had been brief, to be sure, but many lives are, and length alone is no grounds on which to judge.

“I’ve come to warn you,” I said, as the urge passed, “and I’ve no intention of dying. We have to make for the ocean.”

“I chose this pool a hundred years ago, as a yearling. It is my home,” she said.

“You’ll find another.”

“Is that what you do? Go from place to place, rootless?”

“Every time they come after me,” I agreed.

“I can’t live like you. I wouldn’t survive, any more than you’d survive drowning.”

“I want a home,” I said. “I want you to be home. I don’t care where it is, as long as you’re there.”

“I can’t live like you.”

Tears fought their way down my cheeks and I was glad for the cold spray of the falls that disguised them.

“Can you do it this once?” I asked. “Leave your home?”

“No,” she said. “It would be nicer to stay here, don’t you think? Nicer to enjoy one another, then fight and die?” She kissed me then, and I had endless time to consider it.

She might have kissed me longer than I thought, because when my mouth broke from hers, I heard a distant crashing that likely couldn’t be anything but an armored man sliding down a slope.

I took her by the hand. I had no weapons but a knife, and no training in combat. If I stayed, it would be purely symbolic. There was no reason not to run, not to save myself. Still, I didn’t let go.

“I see them!” someone shouted. “There, in the pool!”

“Just a couple of girls!” another man’s voice called back. He kept speaking, too, after that, but I couldn’t make out the words.

I couldn’t see them. They were hidden by the trees.

I tried to lead the Lady away, but she resisted.

“We can’t fight them all,” I said.

“Yes we can,” she said. “We might not be able to stop them all, but we can certainly fight them.”

Then they came out of the woods as fog began to rise, and they were terrible. The white-painted armor of the King lent them a ghostly look, made worse by the rising fog and the starlight. Their pikes were death, their swords were death, and contrary to every song ever sung, death is the opposite of love.

I wanted love.

My body was numb with adrenaline and cold water, and I was up to my waist in the pool. I got my knife into my hand.

They approached with their pikes and shouted their words that insisted on surrender but I don’t know that I heard them or anything at all.

A spear reached for me, and the Lady took it by the haft and pulled its wielder off balance, and another spear sliced her shoulder while she did and her dark blood ran into the water. More spears were coming.

Something broke in her as her skin split apart. “You’re right,” she said. “I’ll make for the ocean.”

We dove under, swam until the pool grew too shallow, then ran along the creek.

As I vaulted a fallen log, I rested my left hand on the trunk of a nearby tree for balance. A crossbow bolt shot through my palm, pinning me.

The Lady broke the shaft of the quarrel and I pulled free my hand. Another bolt cut through my cape.

Every obstacle we crossed increased our lead, because a thief and a fey can move faster through the woods than those who are armed and armored. Soon they gave up on shooting at us entirely. Soon after, we couldn’t hear them.

“They know we’re following the creek,” I said. “If we break from it, we can lose them in the fog.”

“If I can’t be in my pool, I need to be in the ocean. You can hide in the fog. I can make my way alone.”

“No,” I whispered, and kept going, my wounded hand wrapped in my cloak.

We reached the top of another waterfall, one that sent the creek cascading down to the beach. I looked down into the dark gray nothing of the morning. Somewhere down there was the ocean, and presumably Henrietta on the beach nearby. It wasn’t too late for the spell.

It would be a hell of a climb to get down there, however.

The Lady turned to me, looked me in the eyes. She was searching, trying to understand me.

“There’s a witch,” I said, as I held her by the waist, “meeting me at the beach. She said she can transform me.”

“Into a creature of the sea?” the Lady asked.

“Yeah.”

“Is that what you want?”

“I want to be with you,” I said. “However I can.”

“Then do it,” she said. Her eyes were still searching my face. “Be with me.”

Was there no passion in her voice because I didn’t know how to listen for it? Was there no passion in her voice because there was none in her heart? Or was there passion, deep passion, and my terror kept me from hearing it?

Without another word, the Lady knelt down and climbed over the edge of the cliff. I’d have to climb down after, with my left hand useless.

Nothing to do but to do it. I knelt down, looking for a ledge.

A crossbow bolt found my leg and I pitched forward, down into the fog, down into the gray.

The ocean has its own kind of cold, a rough and salty cold that will kill you as sure as the snowmelt cold of mountain rivers. I hit that cold and it cracked me into consciousness, but my leg wouldn’t respond to my commands and my hand was warm with blood.

There was no surface in sight.

I’d tried. No one could say I hadn’t tried.

Most people would say I’d gotten what I deserved, and maybe they’d be talking about me being a thief and murderer but more than a few would say it because I was a monster and I’d always been a monster.

Nettle and Fitch would miss me, and Fitch might miss me for more than my share of the rent. But mourning isn’t always just a hardship, it’s part of the beauty of life. My death might lend them beauty.

I’d also saved my love.

Who, to be honest, I shouldn’t have loved.

Water made its way into my lungs. Cold water shouldn’t feel like fire. It did.

She loved me, in her way. I loved her, in mine. We could have had that love slowly. I could have not become obsessed. I could have fed her men and those men’s coins could have fed me.

Instead, I was drowning.

I closed my eyes because I couldn’t see anything anyway, and there was that fire in my chest. Better to sleep than to burn.

I slept.

I woke on shore with her mouth on mine and the fire was out of my chest, in every way, all at once. I wasn’t drowning anymore. That was her magic. I wasn’t obsessed anymore. That was mine.

Behind her, a stooped giantess of a witch held aloft a raw crystal the size of a boulder. The mist seemed to shrink away from it and her, leaving us in a bubble of clarity in an obscured world.

“Good morning, child,” Henrietta said, with an uncharacteristic giggle in her voice. “I’m glad you could make it.”

“Laria,” the Lady said. Even then, even as I stood on the precipice of death, her face was without emotion.

“I’m fine,” I said, because I wasn’t dead and I probably wasn’t even dying, and by that standard, everything was fine. I struggled to my knees. Gentle waves lapped against me, and the sand was cool beneath me.

“The spell is cast,” Henrietta said. “The dawn will break in a moment, and the first ray will strike this crystal and all you must do is stand in its light if you choose. The Sea Mother will take you for her own.”

“Wait,” I said.

“I cannot.”

“Stand down!” a man’s voice shouted, louder than the waves, echoing against the cliffside.

He approached, a silhouette with a crossbow drawn. The Lady ran at him. He shot once, missed.

He stepped out of the mist and into the circle, dropping his crossbow and drawing a short sword. It was the tracker. He must have come ahead of the rest of the men, being the only one capable of climbing down the cliff.

“Stand down!” he shouted again.

The Lady lunged for his sword hand, but he was too fast. He swung at her and missed.

They danced, both too experienced to easily defeat the other. Since he had friends coming, however, time was on his side.

He cut the Lady, shallow across the other shoulder as she’d been cut before, and her blood ran red. I could see the color this time. It was almost dawn.

“I killed him!” I said, standing, shouting. “I killed that man whose name I don’t care to know; I stole every copper he’s ever taken from a corpse in war.”

It worked. The man turned his attention to me. I limped closer, until I was just outside the range of his blade.

“I am going to live my life on land so that I can kill a thousand like him, starting with you.”

“You won’t kill me, baedling,” the tracker said. “You’ll hang by sundown.”

Dawn broke, the crystal caught the first ray, and it shot toward me. I dove at the tracker. He swung, reflexively, but missed. My body slammed into his legs. He fell over me into the light, into the spell.

Incoherent red rage consumed his body and he blistered and he screamed. His legs fused and grew scales, his neck split open into bloody gills, and he screamed. His teeth fell into the sand and fangs grew in their stead, and he screamed.

The lady took the sword from his hand, held it to his throat.

“Should we gut him?” she asked.

“Help him into the water,” I answered. “Let the Sea Mother take him.”

The Lady and I rolled him across the wet sand and into the waves. He stopped screaming. Soon he was gone, cursed to the depths.

“What now?” the Lady asked.

I had to leave town. The rest of the men would be after me. Maybe Nettle and Fitch would come with me, maybe not. I’d make it work. I had before, I would again.

“We’ll go our ways,” I said. Dawn brought clarity the way it’s supposed to. “I’ll grow old, and I’ll bring you men once every few years.”

“That will be enough for you?”

“It will.”

Copyright © 2018 by Margaret Killjoy

Art copyright © 2018 by Alyssa Winans

Buy the Book

Into the Gray