Mute, Duncan Jones’ long-awaited follow-up to Moon, hit Netflix last month, after a lengthy incubation period. It’s part of Netflix’s current trend of producing and/or acquiring somewhat esoteric genre movies, a trend which began with Bright and continued with The Cloverfield Paradox and Annihilation, up through imminent releases like The Titan. Often these releases are intended for overseas audiences, sometimes global, but the process is ongoing and has so far given us a wide slate of films that have varied from frequently great (Annihilation) to ones that seem to be setting up a far better sequel (Bright).

Mute is something of the middle child in all this, and its reviews have reflected that. Slammed for being an unusual combination of cyberpunk and film noir, as well as for a script that touches on everything from Amish woodwork to the aftermath of Moon, it’s a choppy piece of work, to be sure, but there’s some real worth to it. If nothing else, Paul Rudd and Justin Theroux’s characters and their transition from Cyberpunk Hawkeye and Trapper John into something infinitely darker is compelling stuff, if you’ve got the stomach for it.

But if there’s one criticism of Mute that seems pretty universal, it’s that the film tries to do too much. Cowboy Bill and Duck’s story, Leo’s story, the collision between respectable Berlin and Blade Runner 2049 Berlin, Amish beliefs, toxic masculinity, and the curious requirements of underworld doctors all get mashed together into a story that somehow still finds time for a discussion of sexual perversion, parenthood, and grief, not to mention a truly egregious instance of fridging. It’s an ambitious, often beautiful, sometimes collapsing mess. Given how spare and pared down Moon was, maybe that’s not entirely surprising that Jones has gone in the opposite direction with this “spiritual sequel.” Set in the same universe, Mute expands it in some subtle, fun ways. And whether you love it or hate it (or haven’t around to watching it yet), Mute also gives us a perfect opportunity to revisit Jones’ very first feature film and shine a light on everything that made Moon work.

(Spoilers ahead for Moon.)

Before we go into any further detail, though, we need to address the voiceover artist in the room. It is impossible not to view 2009’s Moon differently now that we’re on the other side of the revelations about Kevin Spacey. His performance here providing the voice of GERTY is invisible, but it’s also omnipresent. There’s even a reading of the film that suggests GERTY deliberately activates the second Sam and that the whole movie has, as its inciting incident, the off-screen ethical awakening of an Artificial Intelligence.

While interesting, especially when considering GERTY’s actions in the third act, whether or not you subscribe to this theory ultimately doesn’t matter. What does is that Spacey’s presence in the film, now, places a particular onus on the viewer. Some will be able to look past the man and focus on the art. Some won’t. This essay works off the assumption that its readers will be in the former camp; it also ascribes no value judgment to either choice. The point of art is that we interact with it on our own terms. Make whatever choice works best for you.

It’s also worth noting, as a sidebar, that Sam Rockwell’s presence in Moon may carry with it the residue of recent controversy for some viewers, albeit for vastly different reasons. Rockwell’s turn in Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri as a racist cop won him an Oscar. As is often the case with Academy recognition, the award can be seen as acknowledging an actor’s cumulative body of work as much as a specific performance, and Rockwell has certainly put in some great work over the years (a fact that fans of Moon can attest to). In the case of Three Billboards, however, the redemption narrative surrounding his character has been a bone of contention, an issue which might drive some potential viewers of that film to the same choice: to watch or not to watch. Either choice is valid. Everyone’s choice will be different.

Returning to Jones’ work, it can be said that Moon, along with films like Pitch Black, Another Earth, and Midnight Special, is one of those movies that approaches the platonic ideal of mid- to low-budget mainstream cinematic SF, at least for me. Where Pitch Black features two star-making performances (only one of which took, unfortunately), Another Earth helped establish Brit Marling as the queen of obtuse SF cinema, and Midnight Special is a glorious, unprecedented explosion of Forteana, Moon is something far closer to classic science fiction. And not the dusty, ivory-tower ideal that never survives contact with daylight or historical context, either; rather, Moon is a story about it means to be human, shot through with an infusion of cyberpunk that somehow manages to avoid all that sub-genre’s often dated and/or pompous trappings. (A trick which it’s successor, Mute, is not quite as successful in pulling off.)

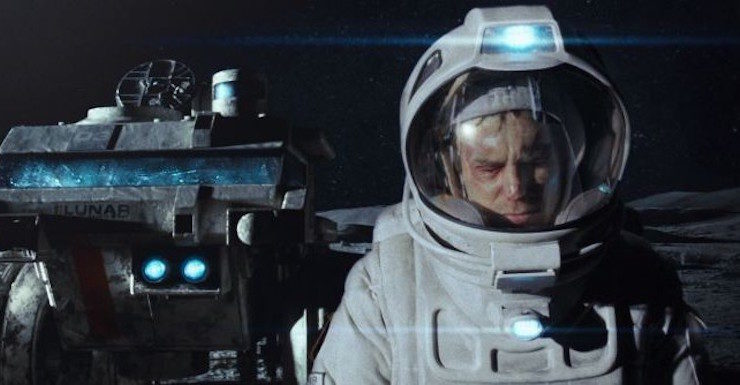

Rockwell stars as Sam Bell, an astronaut monitoring colossal, automated helium harvesters on the far side of the Moon. Sam is at the end of his multi-year tour and struggling to deal with a communications blackout, cutting him off from Earth. When an accident brings him face to face with someone impossible, Sam discovers the truth about who and what he is.

Jones’ direction is careful to the point of minimalism, and continually places his two leading men (or perhaps one leading man, squared?) front and centre. There’s an air of calm and disheveled serenity to Sam’s lunar burrow that makes you feel instantly at home—this is a place where someone lives and works. Untidy, meticulous, human. The simple fact that GERTY, his robotic assistant, has a mug stand tells you vast amounts about the aesthetic Jones aims for and achieves. This is space as workplace, not exotic, romantic final frontier.

The true genius of the film, however, lies in the way Jones hides everything we need to know in plain sight. Just like Sam, searching for the secret chambers of the base, we slowly find ourselves studying every element of his home. How long have those plants been there, to have grown that much? How could Sam have completed so much work on the model village? Why are the comms down? Our gradual unease with the world grows alongside Sam’s own, and Jones never lets up on that. It’s especially notable in moments like Matt Berry and Benedict Wong’s cameo as a pair of not-quite-plausible-enough corporate suits, and the counterpoint between Sam’s “rescue” party’s avuncular greeting, and the looming shadow of their guns on the wall.

That carefully neutral mooncrete canvas is what Jones gives his leading man to work with, and Sam Rockwell manages to fill every inch of it. Rockwell is one of those actors whose prolific back catalogue is surprising when considered in light of how relatively little recognition he’s received, prior to this year. From his epochal turn in Galaxy Quest to his magnificent central performances in Matchstick Men, Welcome to Collinwood, and Seven Psychopaths, Rockwell is mercurial, charismatic, commanding and holding your attention in a deeply weird way. I can’t speak to his work in Three Billboards because I haven’t seen it, but I am curious to see what an actor like Rockwell does with a role and a script that’s divided people so intensely.

Here, he plays Sam Bell as a slowly unfolding, or perhaps collapsing, puzzle. Our glimpse of the amiable space cowherd of the opening sequence slowly becomes a study of accelerated ageing. The newly discovered version of Sam is almost a parody when compared with the previous one: the new model strutting around the base in an immaculate flight suit and aviator glasses, macho where Sam 1 is relaxed, angry where Sam 1 is resigned.

Neither Sam is perfect. Neither man is entirely broken. Together, they form a unique partnership that enables us to look at a life from both ends. The younger Sam, it’s heavily implied, is career-driven, possibly alcoholic, possibly abusive. The film strongly suggests that he took the lunar job because his family didn’t want him around. The older Sam has lost that relentless, clenched focus and aggression. It’s been replaced by a serenity that slowly turns into grief. He knows what’s happening to him long before it’s made overt and we see him work through the stages of the emotional process, especially anger and acceptance, without ever fully articulating what he’s going through. We see the same man not just at two different times in his life, but two different lives in his time, given a chance to confront himself and for both versions to make their peace with one another. Their final conversation, and the way they react to the discovery that neither are the original Sam, is one of the most heartrending, gentle moments in the entire movie, and it’s extraordinary to see Rockwell playing this scene so incredibly well against himself. Just as, years later, we’d also see him do briefly in Mute.

Moon is, in the end, many kinds of story. It’s a discussion of mortality, a brutal takedown of corporate culture, an examination of what is expected of men even when they can’t or won’t do it, and a deflation of the romantic trappings of the astronaut-as-mighty-space explorer myth. It’s a tragedy, an examination of whether the child really is father to the man (or the clone), and a crime story unfolding like a slow-motion punch. It’s blue-collar science fiction with a red, beating heart, and a cyberpunk story that swaps out spectacle and posturing for uncomfortable, raw, vital emotion. It is, above all else, an extraordinary achievement. Mute may not have reached this level of sublimely successful artistry, but when viewed together, these films both have gifts to offer. The first is a look into a complex, untidy, and disturbingly plausible future. The second is a look at a major talent, growing into his abilities, and I remain excited and immensely curious to find out where Jones’ talents will take us next.

Alasdair Stuart is a freelancer writer, RPG writer and podcaster. He owns Escape Artists, who publish the short fiction podcasts Escape Pod, Pseudopod, Podcastle, Cast of Wonders, and the magazine Mothership Zeta. He blogs enthusiastically about pop culture, cooking and exercise at Alasdairstuart.com, and tweets @AlasdairStuart.