Rowenna Miller’s fantasy debut, Torn, starts with great promise. Unfortunately, it doesn’t quite live up to its promises: like many fantasies that flirt with revolution, it ultimately fails to actually critique the system of aristocracy, ascribing the flaws in a system of inherited power down to one or two bad apples and general well-meaning ignorance among the aristocrats rather than the violence inherent in a system that exploits the labour of the many for the benefit of the few.

I hold fantasy that flirts with overturning the status quo to higher rhetorical and ideological standards than fantasy that doesn’t question the established hierarchies of power within its world. It sets itself up to swing at the mark of political systems and political change, which means that when it fails to connect, it’s pretty obvious. When it comes to systems—and rhetorics—of power, the question of who ought to be in charge and how change can—or should—come is deeply fraught and powerfully emotive. And significant: the rhetoric of our fictions informs our understanding of how power operates in our daily lives.

And yeah, I expected Torn to offer a more radical view of revolution.

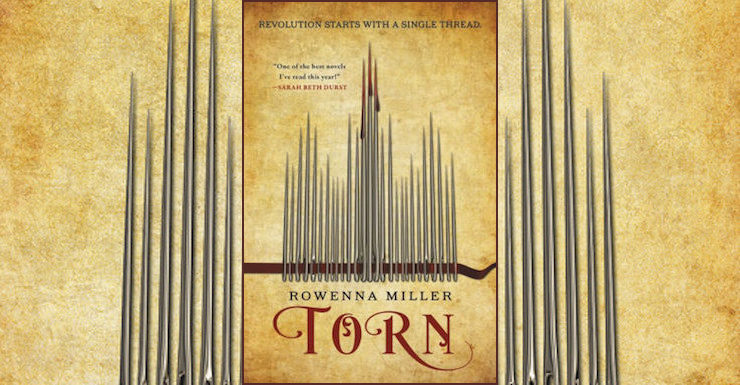

Buy the Book

Torn (The Unraveled Kingdom)

Sophie Balstrade is a dressmaker and a mostly assimilated second-generation immigrant in Galitha. Her parents were Pellian, and she learned from her mother how to cast charms into the clothes she makes, a skill that’s given her a leg up on getting clients and opening her own shop. Her charms give her clients discreet benefits in terms of protection and good fortune, and in return, she’s managed to make herself a business that employs two other people, as well as providing the income that supports her and her labourer brother Kristos. She dreams of more security, of having commissions from nobility and being recognised for the artistry of her dressmaking, not just for the usefulness of her charms. When she receives a commission from Lady Viola Snowmont, she begins to think she might succeed in her ambitions—especially as Lady Viola invites her to attend her salon, where Sophie finds herself received as an artist and a peer with Lady Viola’s eclectic collection of aristocrats and thinkers.

But meanwhile, labour unrest is growing in the city. Sophie’s brother Kristos is a leader in the Laborers’ League, a stifled intellectual shut out from work that he’d find meaningful under the restrictive aristocratic system that strongly limits opportunities for ordinary people. His calls for reforms make Sophie uneasy: she fears for his safety and for her own, and for the costs of a potential crackdown if the Labour League protests escalate into violence—which they seem to be doing. Sophie has conflicted feelings about the system that lets her succeed, albeit precariously, but she doesn’t want to tear it down. The collateral damage would be, in her view, too high.

This sense of conflicted loyalty is compounded when a member of the royal blood—Theodor, a duke and a prince—starts to essentially court her. When Kristos disappears and the leadership of the Laborers’ League threatens Sophie with his death unless she makes a curse for the royal family, a curse that will be used in a coup attempt, her loyalties are brought into much more direct conflict. Sophie’s income depends on the nobility, and more than that, she likes them as people. But with her brother’s life at stake, she has to chose where her highest loyalty lies.

Miller gives Sophie a compelling voice, with an eye for detail and a deep interest in women’s clothing—Miller, it’s clear, knows her stuff when it comes to sewing, hemming, and the logistics of historical styles—and it’s easy to like her and find her interesting. Most of the other characters are well-rounded, deftly sketched individuals, but the more sympathetic ones, and the ones who treat Sophie with respect for both her views and her talents—the ones willing to compromise and learn—are all shown to be members of the aristocratic elite. I can believe in the beneficence of a Lady Viola Snowmont, but that queen and princess and a full array of nobility behave with such respect towards a woman of the lower classes stretches my disbelief.

Torn has tight pacing, a strong narrative through-line, and an explosive climax. I found it very satisfying as a reading experience, at least while I was reading it. But in retrospect, Torn‘s dialogue between revolution and establishment founders on a bourgeois distrust for the working class’s judgment and grievances. It ends up reinforcing its aristocratic status quo, and holding out hope for an enlightened nobility to offer reform to the people. Whether or not that’s Miller’s intention, it makes for an unfortunate conclusion to a promising debut: forgive me if I prefer my fantasy’s political messages to be a little less wait for change to come from above. Especially in this day and age.

As a politically engaged (and over-educated) member of the labouring classes myself, though, I own my biases. This is an interesting novel, a compelling and entertaining read. But it’s also a novel engaged in—in conversation with—political dialectic about change and systems of power, and on that count, it doesn’t examine nearly enough of its assumptions.

But I look forward to seeing what Miller does with the sequel.

Torn is available from Orbit.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, is out now from Aqueduct Press. Find her at her blog, where she’s been known to talk about even more books thanks to her Patreon supporters. Or find her at her Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council and the Abortion Rights Campaign.