In 1996, I was a history graduate student on the fast-track to burning out. When I looked across my professional horizon, I saw only frustration and defeat. I had been on the path to becoming a professor for a while and had one remaining hurdle—my dissertation. But my research in Italy had foundered upon the rocks of the Byzantine system that predated online searches. It was the good old days of hands-on archival work—dusty books in dimly lit recesses of moldering libraries. My research bordered on archeology as I shifted and sorted through papers, looking for the clue that might lead me to documents crucial to my dissertation.

After months of searching, I had, with the help of a librarian at the National Library in Florence, finally unearthed the documents I needed about Anna Maria Mozzoni, an Italian suffragist and feminist. They were in Turin. But the archive was closed until the first week in September. They would open four days after I was scheduled to return home. I had neither the funding nor the personal resources to prolong my trip. I left Italy without ever seeing the documents I had spent months looking for. Without them I would have to rewrite my entire thesis.

Back in California, I was at loose ends. The academic year would not start for another month, and I was stuck. For long hours, I sat at my desk, staring at the books and papers I had accumulated, wondering if I could write my dissertation without those documents in Italy, slowly coming to terms with the fact that I would need to come up with a new topic. I shifted from my desk to the couch and sat with my failure, unwilling to admit I no longer had the drive to continue. My housemate, concerned about me, returned one evening from her job at the local bookstore and handed me a book.

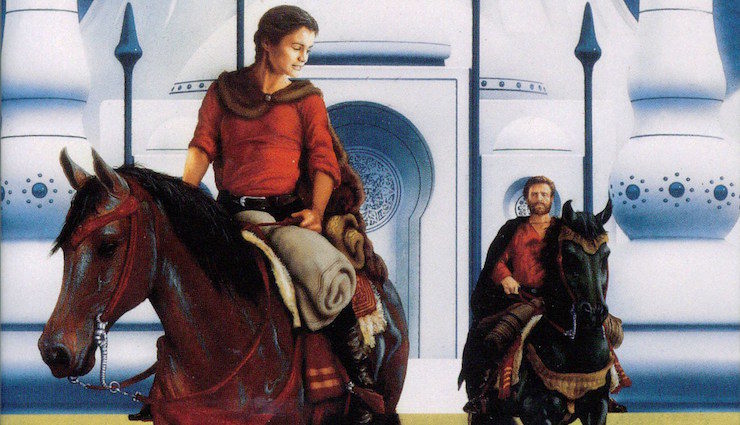

“Read this,” she said. Her tone and expression made it clear she would brook no argument. The book was Kate Elliott’s Jaran.

Buy the Book

Jaran (The Jaran, Book 1)

Eager to avoid reality, I gratefully lost myself in an alien-dominated galaxy, where the book’s main character, Tess Soerensen, stows away on a shuttle bound for the planet Rhui. Tess is trying to escape from not only romantic disillusionment, but also her responsibilities as heir to her brother, the rebel leader of the conquered humans. On Rhui, Tess joins with the planet’s native nomadic people, immersing herself in their culture and rituals, as she tries to balance duty and personal power.

With its anthropological underpinnings, a hint of Regency-era romance, and adult coming of age conflicts, Jaran spoke to me. In Elliott’s gracefully arcing saga, I saw reflections of myself. Tess had just finished her graduate studies in linguistics. I was a graduate student. The feminist studies classes of my first years were echoed in the matriarchy of the Jaran nomads. And the polyamory of the native Jaran dovetailed with the free love movements of the utopian socialists and early 20th century anarchists I had researched. But it was in Tess’s struggle to balance her duty to her brother and her desire for autonomy that I saw myself most directly.

The truth was, I liked studying history, but I didn’t love it. I thought it would be my profession, but it wasn’t my passion. My passion was surfing—an avocation that would never be a profession. Over the next several months, as I finished Elliott’s Jaran series, I struggled with my parents’ expectations, my responsibilities to my dissertation advisor, and my longing to do what would make me happy. I taught my classes. I made gestures toward the dissertation to stave off its inevitable failure. All the while I dreamed of waves.

In January of 1997, shortly before my 30th birthday, I turned in my paperwork to officially withdraw from my graduate program. My parents expressed profound disappointment in me. They worried about how I would support myself. They bullied me to change my mind. But I was resolute.

I spent the next several years working odd jobs, often more than one, to support myself. And I surfed. Every day. I spent long hours in the ocean, looking at the horizon, waiting for waves. I felt at once alive and at peace. In the long days of summer, when the waves gently peeled around the rocky point, I would often stay out past sunset, repeating the surfer’s mantra, “Just one more.” When I could no longer distinguish wave from shadow, I would pad up the crumbling concrete stairs, water dripping from my board, salt drying on face, and my feet tender because even in summer the ocean in Northern California is chilly. I would strip out of my wetsuit, curb-side, under the glow of a streetlight and the even fainter glimmer of stars. The measure of my day was not in the number of waves I caught but in the fullness of my heart.

When winter came, the water turned cold and menacing. I would sometimes spend an hour trying desperately to paddle out through waves intent on crushing me and pushing me down into the dark churning depths. All for a few precious moments of screaming down the face of a wave with the white water chasing me onto the shore. On land, breathless and shaking from adrenaline and effort, I would momentarily question the sanity of risking so much, but I never regretted my decision to leave graduate school. Each day, upon my surfboard, I quite literally looked upon a horizon far wider and more fulfilling than anything I had ever imagined or experienced in my academic work.

I did not leave graduate school because I read Jaran. The relationship is neither causative nor that simplistic. Rather, I read Jaran as I contemplated for the first time my own needs, separate from family and society. The book stands out in my mind as a turning point in my decision to prioritize pursuit of a passion over the pursuit of a profession. This choice, my choice, led to some of the happiest years of my life and it has emboldened me to commit to one of my riskiest undertakings so far—becoming a writer.

I still look to the horizon. Now more often from the shore than from my surfboard. The broad expanse of blue ocean holds me transfixed. I note the direction of the swell, and I count the intervals between the waves. I also envision the stories I need to tell, the characters I want to explore, and the hope of a profession I am passionate about.

Tina LeCount Myers is a writer, artist, independent historian, and surfer. Born in Mexico to expat-bohemian parents, she grew up on Southern California tennis courts with a prophecy hanging over her head; her parents hoped she’d one day be an author. The Song of All is her debut novel.

Tina LeCount Myers is a writer, artist, independent historian, and surfer. Born in Mexico to expat-bohemian parents, she grew up on Southern California tennis courts with a prophecy hanging over her head; her parents hoped she’d one day be an author. The Song of All is her debut novel.