I don’t want to make you jealous or anything, but at least once a year I get to teach Beowulf.

I know, I know. You probably skimmed it once in some first-year literature survey class and you didn’t like it and … friends, you’re missing out. Beowulf is amazing. There’s a damn good reason that J.R.R. Tolkien was fascinated with it his whole life.

(True story: I spent days in the Tolkien Archives poring over his handwritten translations of the poem, annotations, and lecture notes. The recent Beowulf volume put out by the Tolkien Estate does not do the professor’s work justice.)

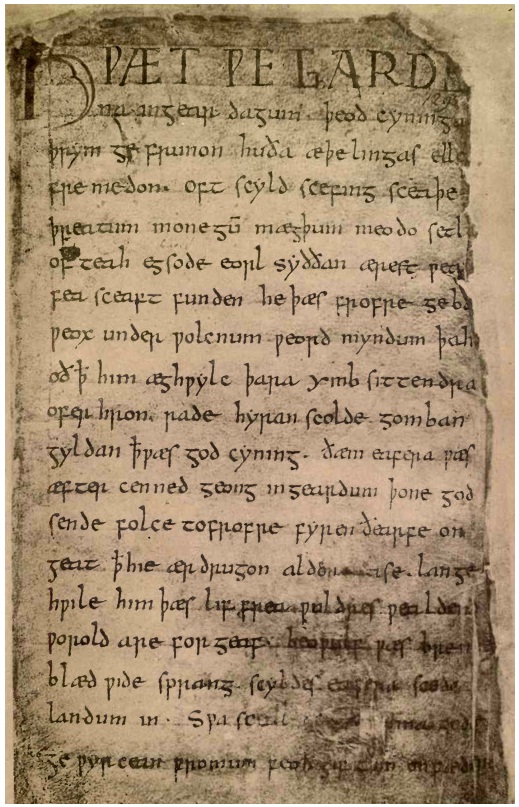

The thing is, though, that most people don’t really get how deeply and powerfully resonant Beowulf remains—over a thousand years since monks wrote our sole surviving copy of it. Unless you had a great teacher who could bring the culture alive—political and social nuances intact with the astonishing power of its verses—it’s likely that you viewed this great English epic as more of a class speed bump more than an extraordinary masterpiece.

Alas, I wish I could say that Hollywood has stepped up to fill in the gaps. Some of my colleagues might hate-mail me for this, but there are some great works of literature that are actively helped by having terrific film adaptations: the immediacy of visual presentation, along with its unpacking of action and character development, can at times serve as a bridge for people to access the text. I’m thinking at the moment of Ang Lee’s 1996 adaptation of Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility (starring Emma Thompson and Kate Winslet) or Oliver Parker’s 1995 adaptation of William Shakespeare’s Othello (starring Laurence Fishburne and Kenneth Branagh)—movies that are equal to the task of representing the magnificent words from which they were fashioned.

For Beowulf, no such film exists. What do we have instead? Well, below I’m going to give you a list of my top five Beowulf movies (sorry, TV, I’m looking at the big-screen here).

First, though, a Beowulf primer:

Act 1. A monster named Grendel nightly terrorizes the hall of Hrothgar, king of the Danes. Beowulf, a young hero from the land of the Geats (in modern-day Sweden), comes to Daneland and rips off Grendel’s arm. The people party.

Act 2. Grendel’s Mother crashes the party, and Beowulf goes into the mere after her. When he finds her he kills her, too. The people party.

Act 3. Fifty years later, Beowulf has risen to become king of the Geats back home, and a dragon in Geatland is awoken from its slumber when a thief steals a cup from its horde (cough, The Hobbit). Beowulf fights the dragon alone at first, then with the help of a single loyal companion defeats the beast. Alas, Beowulf has been wounded; he dies, his body is burned upon a pyre. The people mourn.

Or, to put it another way, here’s the gist from Maurice Sagoff’s Shrinklit:

Monster Grendel’s tastes are plainish.

Breakfast? Just a couple Danish.King of Danes is frantic, very.

Wait! Here comes the Malmö ferryBringing Beowulf, his neighbor,

Mighty swinger with a saber!Hrothgar’s warriors hail the Swede,

Knocking back a lot of mead;Then, when night engulfs the Hall

And the Monster makes his call,Beowulf, with body-slam

Wrenches off his arm, Shazam!Monster’s mother finds him slain,

Grabs and eats another Dane!Down her lair our hero jumps,

Gives old Grendel’s dam her lumps.Later on, as king of Geats

He performed prodigious featsTill he met a foe too tough

(Non-Beodegradable stuff)And that scaly-armored dragon

Scooped him up and fixed his wagon.Sorrow-stricken, half the nation

Flocked to Beowulf’s cremation;Round his pyre, with drums a-muffle

Did a Nordic soft-shoe shuffle.

I’m skipping whole rafts or nuance and intricacy, but this is good enough to get us started.

So, on to the film versions:

5. Beowulf (1999; dir. Graham Baker)

One of the things that screenwriters seem desperate to do is explain Grendel. This was true before John Gardner’s novel Grendel hit the shelves in 1971, and it’s only gotten worse since. Why does Grendel attack Hrothgar’s hall?

The poem, of course, makes no answer. Grendel is the wilderness, the terror of the black night, the lurking danger of what’s just beyond the reach of civilization’s light. It needs no explanation because it cannot be explained. The original audience understood this, but Hollywood folks seem altogether wary of trusting that modern audiences will. (Not just Hollywood, I should say, since Grendel was a huge turning point for what my friend John Sutton has called Beowulfiana; for more on this, check out the article we wrote together on the subject.)

Anyway, in this post-apocalyptic retelling of Beowulf, starring Christopher Lambert as the leading man, we are given a rather inventive backstory for Grendel: he is the unwanted son of Hrothgar, who slept with Grendel’s Mother, who happens to be an ancient demoness whose lands Hrothgar subsequently took from her. Oh, and Hrothgar’s wife committed suicide when she found out about the affair, which totally removes the insightful political dynamics centered on Queen Wealhtheow in the poem.

Also, Beowulf gets a love interest in the form of Hrothgar’s daughter who is remarkably good-looking despite living in a post-apocalyptic hellscape … which the director emphasizes with several unsubtle cleavage shots.

Classy it is not.

Also, the movie completely omits the entire third act of the poem with the dragon. I’d be more mad about this if it wasn’t common to most of the adaptations.

4. Beowulf (2007; dir. Robert Zemeckis)

This should have been so good. The script was written by Roger Avary (Trainspotting) and Neil Gaiman (the man, the myth, the legend), the director is great, and the cast is terrific. Why doesn’t it work? Part of it is the motion-capture CGI that Zemeckis was working with (here and in Polar Express): it makes a character that is simultaneously too real and too fake, making it a go-to example for defining the “uncanny valley.”

The movie also takes huge liberties with the text. As with our previous entry, the filmmakers couldn’t go without providing some kind of explanation for why Grendel does what he does. In this case, it turns out that Grendel’s Mother is a gilded naked Angelina Jolie who is some kind of semi-draconian shapeshifter that lives in a cave. Hrothgar has sex with her (what’s up with this?) and promised to make their son his heir. Alas, Grendel turned out sorta troll-like. When Hrothgar held back on his promise, as a result, the terror began.

And that’s just the start of the textual violence. When Beowulf goes to fight Grendel’s Mother, he doesn’t kill her; instead, repeating history, he, too, has sex with Golden Angie. Yeah, it’s true that in the poem Beowulf brings no “proof” of the killing back with him, but it’s quite a stretch indeed to suggest they had sex and thus Beowulf became the dad of the dragon that plagues Hrothgar’s Kingdom fifty years later when Beowulf takes the throne. Yes, to make this work they had to collapse all the geography and thus nuke the political dynamic of the poem. Ugh.

Unfortunately, this seems to be the go-to movie for students who inexplicably don’t want to read the poem—probably because it has, as noted, a gilded naked Angelina Jolie. It’s only classroom usefulness, though, is as a good answer to students who question whether the sword can really be a phallic symbol.

(Also, you can be sure that I write test questions to deliberately trip-up students who watched this poem-in-a-blender.)

3. Outlander (2008; dir. Howard McCain)

Another science fiction version, billed on the poster as “Beowulf Meets Predator”! This one stars James Caviezel as a space-farer named Kainan who crashlands his alien spaceship in a Norwegian Lake in the Iron Age. His ship, it turns out, was boarded by a creature called the Moorwen, which is the last of a species that space-faring humans tried to wipe out when they were colonizing another planet. The Moorwen caused Kainan’s ship to crash—conveniently waiting to do so after it reaches Earth, which is a past “seed” colony, too, we’re told.

Escaping from the wreckage, Kainan runs into a Viking named Wulfgar (this is the name of the coastal watchman that Beowulf first encounters in the poem), who in turn takes Kainan to Rothgar, a stand-in for the poem’s King Hrothgar—played by the always wonderful John Hurt. Kainan tells them the Moorwen is a dragon, which allows the film to combine that pesky third act of the poem into the first two acts. This collapsing of the poem is furthered when the Moorwen has offspring partway through the movie: Grendel’s Mother is the Moorwen, Grendel its child, and the dragon essentially both.

To top it all off, the movie wraps a kind of quasi-Arthurian spin on the whole thing, as Kainan needs to forge an Excalibur-ish sword out of spaceship scrap metal in order to defeat the Moorwen. It’s sorta insane.

I can’t say that this is a particularly good film—shocker with that synopsis, amiright?—but this bizarre take on Beowulf is so crazy that I find it oddly endearing.

2. Beowulf & Grendel (2005; dir. Sturla Gunnarsson)

If you’re looking for a Beowulf film that feels accurate to the tone and plot of the original poem—though it omits the dragon episode—this is the best bet. It takes some significant detours from the poem by giving Grendel a backstory, Beowulf a love interest, and adding in a subplot about Christian missionaries converting the pagan world … but it nevertheless gets things more right than wrong.

Grendel’s backstory? He and his father are some of the last of a massive race of blond cromagnon-y folks that the Danes believe to be trolls. Hrothgar and his men hunt them down, and a hiding child Grendel watches his father slain by them. Years later he grows to a massive size and begins exacting his revenge.

Gerard Butler makes for an excellent Beowulf, and the first we see of the character is him trudging ashore after his swimming match with Breca—a lovely side-story in the poem that pretty much tells you everything you need to know about Beowulf’s character. He comes across the sea to help Hrothgar, just as in the poem, and he ends up becoming the lover of a local witch named Selma who has been raped by Grendel (though she isn’t sure that Grendel, who is shown as simple-minded, knows what he’s done). Beowulf fights Grendel and kills him, then fights a sea-creature that turns out to be Grendel’s Mother.

Aside from keeping a bit closer to the poem, one of the great strengths of this film is that it was shot in Iceland. The scenery is stark but beautiful, and it feels remarkably true to the cultural memory behind Beowulf.

1. The 13th Warrior (1999; dir. John McTiernan)

I’ve already written one article proclaiming my high regard for this film, and there’s no question that it’s my favorite Beowulf adaptation. We get all three acts of the poem here—Grendel, Mother, and dragon—through the eyes of the very real Arab traveler, Ibn Fadlan (played by Antonio Banderas), who didn’t do much of what’s depicted after the first few minutes of the film. Based on Eaters of the Dead, a novel by Michael Crichton, 13th Warrior does a great job of building a historically plausible look at something that might explain the development of the Beowulf legend.

Well, plausible except that the timeline is broken, the armor ranges from the 5th to the 18th centuries, the herd at the end is untenable, and … ah, shoot, it’s a damn good movie despite all that!

So there you go. Five adaptations of one of the greatest epics in English literature … each of them in some way flawed. The moral of the story, I believe, is that Hollywood needs to do another to try to get Beowulf right.

My agent is waiting by the phone, producers. Let’s do this.

Michael Livingston is a Professor of Medieval Culture at The Citadel who has written extensively both on medieval history and on modern medievalism. His historical fantasy trilogy set in Ancient Rome, The Shards of Heaven, The Gates of Hell, and the newly released The Realms of God, is available from Tor Books.

Michael Livingston is a Professor of Medieval Culture at The Citadel who has written extensively both on medieval history and on modern medievalism. His historical fantasy trilogy set in Ancient Rome, The Shards of Heaven, The Gates of Hell, and the newly released The Realms of God, is available from Tor Books.