I recently found myself combing through some boxes of old books and papers and came across a fascinating personal artifact. On the surface it’s a pretty unremarkable object, just a crumbling spiral-bound notebook covered in childish graffiti. But inside is over a decade of my life—a handwritten list of every book I read between 4th grade and college graduation. Looking through it was a bit like spelunking into the past, a unique look at the strata of different life stages, delineated by changes in handwriting and shifting interests like so many compressed layers of rock.

Paging through the tattered old list, I was seized by a sort of anthropological interest. If different parts of the list reflect phases of my life, what would happen if I took a deep dive into one of these distinct stages and revisited some of those stories? One place in particular caught my interest: from about the age of 12-15 there is a sort of genre bottleneck where my tastes suddenly narrowed from an indiscriminate mix of anything and everything to a very distinctive preference for fantasy and (to a lesser extent at the time) science fiction. There were dozens of titles to choose from, so I picked a handful of stories that conjured up particularly strong feelings, like sense memories that come back clearly even when my actual recollection of the stories is hazy (or nonexistent).

I’m a nostalgic person by nature and I don’t generally shy away from re-reading stories I’ve enjoyed. This little experiment felt different, however, since it goes back further into the past than I’ve ever really attempted before. Everything is more vivid, more important, more oh-my-god-I’m-going-to-literally-die when you’re a teenager, so while I was immediately all-in for revisiting these stories, I couldn’t help but be a little nervous about somehow ruining their lingering effect. Will they still hold up? What will they say about me as a reader, then and now? Did they really shape my tastes as much as I think they did, or was it just chance?

The eight titles I finally settled on actually tell four stories. Two of the books, Firegold and Letters from Atlantis, are standalone stories, while the Dalemark Quartet and what I will call the Trickster Duology are larger stories split into multiple volumes. As I was reading, I noticed that each story falls into a general type, so that is the approach I’ve taken in looking at them here. None of them are considered iconic genre classics and some of them are even out of print. With so many titles to revisit all at once, I can’t delve as deeply into each one as I might like to, but hopefully enough ground can be covered that maybe a few of these stories will get a second life with new readers, or spark a similar experiment for those as nostalgically-inclined as I am. (I’ve also adhered to a mostly surface-level summary of the stories to avoid major spoilers.)

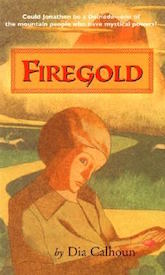

The Coming-of-Age Story: Firegold by Dia Calhoun

Starting with Firegold feels a bit like beginning at the end. Published in 1999, it is the most recent of the books, but it seems right to look back on my angsty early teenage years with a novel brimming with that same turmoil and confusion.

Starting with Firegold feels a bit like beginning at the end. Published in 1999, it is the most recent of the books, but it seems right to look back on my angsty early teenage years with a novel brimming with that same turmoil and confusion.

Firegold is the story of Jonathon Brae, a boy caught between two different worlds. Born with blue eyes, he doesn’t fit in with the brown-eyed farmers of his home in the Valley and, thanks to local superstition, lives in constant fear of going insane. When he turns 14 (the same age I was when I read the story—what perfect synchronicity!), the truth finally starts to emerge and he leaves home to figure out if he belongs with the blue-eyed “barbarians,” the Dalriada, who live in the mountains, or in the Valley and the life he has always known. The story is light on fantasy elements; it uses some limited magic to emphasize symbolic changes and the overwhelming feelings of growing up, transforming the intense emotions of adolescence into a literal life-or-death struggle. Which really helps the angst go down smooth.

Looking back, I can see why the book left a strong impression on my mind, even if I didn’t immediately recognize the parallels to my own life at the time. Beyond the standard quest for identity that defines the coming-of-age story is the idea of being split between two very different ways of living in the world. The Valley people are hard-nosed, conservative, and agrarian, while the Dalriada are nomadic warriors with a strong spiritual tradition (pretty obviously influenced by Native American cultures). My parents’ shotgun marriage ended before I was old enough to talk and I grew up awkwardly split between two very different families—religious conservative but tight-knit on one side, unreliable liberal agnostics on the other—and I never figured out how to fit completely into either. Jonathon, in his search for identity and a place in the world, manages to do something only fantasy stories really seem to allow: by means both magical and mundane, he finds the symbolic bridge between the two worlds (something I’ve never quite managed to do). The real world makes you choose sides and I can’t help but appreciate a story that let me believe, for a little while, that maybe I could do the same.

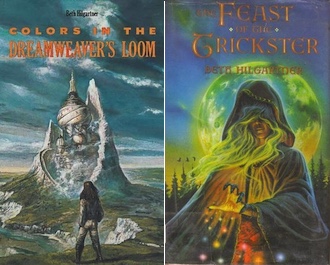

The Misfit Heroes: The Trickster Duology (Colors in the Dreamweaver’s Loom and The Feast of the Trickster by Beth Hilgartner)

Like Firegold, the Trickster Duology (not an official title but easy shorthand here) is a story rooted in adolescent experience. Beginning with Colors in the Dreamweaver’s Loom, Alexandra Scarsdale, who goes by “Zan,” is dealing with the death of her distant father when she is inexplicably transported to an unnamed, preindustrial world of magic and meddling gods. As she is sucked into the complicated politics of this mysterious new place, she reluctantly undertakes a quest, discovers a latent talent, and builds a group of friends and allies that are all outsiders or rejects in one way or another. As with most stories featuring ragtag heroes on a journey, the very characteristics that set them apart and make them different are the same qualities that make them perfect for the roles they need to play. It’s a fairly standard premise on the surface, made interesting by the care the author, Beth Hilgartner, takes with the characters and her instincts for avoiding absolute clichés. Colors ends on a surprisingly dark cliffhanger that sets the stage for a very different sequel.

Like Firegold, the Trickster Duology (not an official title but easy shorthand here) is a story rooted in adolescent experience. Beginning with Colors in the Dreamweaver’s Loom, Alexandra Scarsdale, who goes by “Zan,” is dealing with the death of her distant father when she is inexplicably transported to an unnamed, preindustrial world of magic and meddling gods. As she is sucked into the complicated politics of this mysterious new place, she reluctantly undertakes a quest, discovers a latent talent, and builds a group of friends and allies that are all outsiders or rejects in one way or another. As with most stories featuring ragtag heroes on a journey, the very characteristics that set them apart and make them different are the same qualities that make them perfect for the roles they need to play. It’s a fairly standard premise on the surface, made interesting by the care the author, Beth Hilgartner, takes with the characters and her instincts for avoiding absolute clichés. Colors ends on a surprisingly dark cliffhanger that sets the stage for a very different sequel.

Picking up where Colors left off, The Feast of the Trickster takes a sharp turn and brings Zan’s magical, mismatched companions into the world of modern (1990s) New England. The narrative lacks a single uniting thread like that of the first book, but the stakes of the story are much higher, which complicates things when the tone takes a sharp left turn early on. It is a less conventional story than Colors, more Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure than a Tolkien fellowship in a lot of ways, but still manages to make some interesting observations about growing up and figuring out where you belong. And it does bring closure to Zan’s story in a fairly satisfying way.

These are the only books chosen for this personal project that are currently out of print, and while I think they deserve a chance to find new readers, I can also see how the abrupt shift in tone between the two novels might leave some readers confused. The Trickster books were published in the late 80s and early 90s, at a time when YA was still an unofficial and very loosely-defined label, used mostly by librarians; bridging the gap between children’s stories and more adult fare is tricky work. Sometimes Hilgartner stumbles a bit in Feast of the Trickster, but overall these stories are not just a great adventure, but a look back at young adult writing as it was separating itself into its own unique form, not quite kid lit but not quite fully adult fiction.

As for my own personal connection with Hilgartner’s books, I think being a weirdo—and finding other weirdos to be weird with—is perhaps the single best way to survive growing up. Like Zan, I woke up in a very different world when I was pulled out of a tiny religious school and placed in a public high school for the first time. Finding my own band of misfits and weirdos was how I survived, and how most of us make it through the darker days of adolescence.

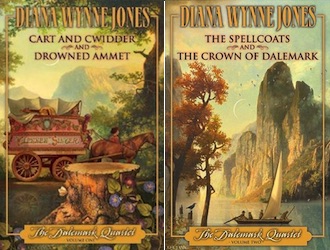

The Epic Fantasy: The Dalemark Quartet by Diana Wynne Jones

The Dalemark books represent some of the earlier, generally less famous work of Diana Wynne Jones, the author probably best known for Howl’s Moving Castle and The Chronicles of Chrestomanci. An epic story told in four parts—Cart and Cwidder, Drowned Ammet, The Spellcoats, and The Crown of Dalemark—the plot revolves around politics and prophecy in the titular Dalemark: a magical, somewhat medieval-ish country that is pretty standard as far as fantasy worlds go. Wynne Jones subverts some common fantasy conventions (and our expectations) by focusing less on the sword-and-sorcery aspect of the story, while also avoiding the episodic pitfalls of multi-volume fantasy by creating fantastic characters and plots that seem mostly unconnected from book to book until they are woven together (quite brilliantly) in the final volume. In comparison to the Trickster novels, the Dalemark stories feels less like books struggling to figure out where they belong and more like YA as we recognize it now—sure of its audience and of the reader’s ability to grasp complex ideas, without transforming the young characters into miniature (and unbelievable) adults.

The Dalemark books represent some of the earlier, generally less famous work of Diana Wynne Jones, the author probably best known for Howl’s Moving Castle and The Chronicles of Chrestomanci. An epic story told in four parts—Cart and Cwidder, Drowned Ammet, The Spellcoats, and The Crown of Dalemark—the plot revolves around politics and prophecy in the titular Dalemark: a magical, somewhat medieval-ish country that is pretty standard as far as fantasy worlds go. Wynne Jones subverts some common fantasy conventions (and our expectations) by focusing less on the sword-and-sorcery aspect of the story, while also avoiding the episodic pitfalls of multi-volume fantasy by creating fantastic characters and plots that seem mostly unconnected from book to book until they are woven together (quite brilliantly) in the final volume. In comparison to the Trickster novels, the Dalemark stories feels less like books struggling to figure out where they belong and more like YA as we recognize it now—sure of its audience and of the reader’s ability to grasp complex ideas, without transforming the young characters into miniature (and unbelievable) adults.

My fond memories of Dalemark are less about navel-gazing and seeing myself in the stories and more about how they taught me how to love a certain kind of storytelling. Compared to later beloved series like A Song of Ice and Fire or the Deverry books by Katharine Kerr, the Dalemark stories are rather simplistic (though they are still incredibly fun to read). But at the time I first read them—somewhere around the age of 13 or so—they were mind-blowing. I had never experienced a story told in quite this way, where each book can essentially stand alone as a story, and yet when read all together (and in the right order, which is crucial since they are not entirely chronological) they suddenly reveal a much larger and more ambitious focus in the final installment, The Crown of Dalemark. Thankfully, this series is still in print and may introduce a host of other young readers to the joys of big, ambitious stories with just the right amount of comforting fantasy tropes and clever, subtle subversions. I also may or may not have developed my first fictional crush on the character of Mitt…

The Speculative Journey: Letters from Atlantis by Robert Silverberg

Letters from Atlantis is, solely by chance, the lone science fiction story on this list, though in some ways it’s a science fantasy as much as it is a speculative story. It’s also the only story that didn’t really hold up for me. As the title suggests, the story is told through letters; the plot revolves around the conceit that in the near-future, historians have the ability to project their consciousness through time to reside in the minds of historical figure, thereby exploring the past first hand. One such historian travels back to the distant past to uncover the “truth” about the lost civilization of Atlantis (hence science fantasy) and uncover the events that led to its collapse. As with most time travel stories, the historian starts meddling in the past, which leads to complex repercussions.

Letters from Atlantis is, solely by chance, the lone science fiction story on this list, though in some ways it’s a science fantasy as much as it is a speculative story. It’s also the only story that didn’t really hold up for me. As the title suggests, the story is told through letters; the plot revolves around the conceit that in the near-future, historians have the ability to project their consciousness through time to reside in the minds of historical figure, thereby exploring the past first hand. One such historian travels back to the distant past to uncover the “truth” about the lost civilization of Atlantis (hence science fantasy) and uncover the events that led to its collapse. As with most time travel stories, the historian starts meddling in the past, which leads to complex repercussions.

Coming back to this story as an adult, I find that I don’t have a particularly deep personal connection with Letters, though I remember being deeply fascinated by it when I was younger. Revisiting it has, however, taught me something about what I now expect a good story to do—or in this case, not do. For one thing, I expect the writer to take the reader’s credulity seriously, and the idea that an individual hiding in someone else’s mind would write physical letters is laughable. There is also the issue of consent—at twelve or thirteen, it never occurred to me that the concept of literally hiding in someone else’s mind is, frankly, kind of horrifying, from an ethical standpoint. What could possibly justify that kind of intrusion into what should be the inviolable space of the human mind? According to this story, curiosity and intellectual discovery trump the right to privacy. I hope that this means the possibilities of the intriguing premise blinded Silverberg to the creepy implications of this storytelling mechanic, rather than the possibility that he knew it was gross and/or problematic and went with it anyway. I also wonder if this is less a failure of vision than the inability of an author to take a young adult audience seriously. Either way, I can’t salvage it.

If anything, revisiting this story tells me something about how I think about my own autonomy now, versus when I was younger and beholden to adults who didn’t believe kids needed any private spaces for their thoughts and feelings. The premise of Letters from Atlantis has a lot to offer, if only the execution had been better. Robert Silverberg is a titan of science fiction but writing for a young adult audience takes more than a hook and an interesting setting. Ending the survey on this negative note might seem a bit counterintuitive, yet of all the books I reread for this piece, my reaction to this one seems to reveal the most about who I am now, and the reader I’ve become over time, rather than projecting back the thoughts and reactions of the person I once was.

Results

Overall, I’d say this foray into the past has yielded some interesting results. I’ve been trapped in a bit of a reading rut for a while now, and looking back on these stories has in many ways reinvigorated the joy I find in fiction. On a more experimental level, revisiting these stories certainly revealed some patterns that I had never noticed before, and showed me how books have always been my most effective tool for understanding the world. Perhaps most interesting is realizing how fantasy can provide the ideal setting to deal with issues that can feel all too real. My shift from being an indiscriminate sponge of a reader to a self-identified SFF nerd as I grew up is not a new story—genre fiction has long been the refuge of the lost and confused and I was (and still am) quite a bit of both.

If I replaced these stories with half a dozen others from the same period, would my conclusions be different? I think so. The stories that we remember in an emotional, bone-deep way are always far more than clever plots and worldbuilding. The ones that stick with us as feelings, resonating even after the narrative details have faded, hold a special place in a reader’s life, shaping future experiences in a way that can only be fully appreciated when we look backwards.

Amber Troska is a freelance writer and editor. When she isn’t reading, you can find her re-watching Stranger Things again.