Binti has returned to her home planet, believing that the violence of the Meduse has been left behind. Unfortunately, although her people are peaceful on the whole, the same cannot be said for the Khoush, who fan the flames of their ancient rivalry with the Meduse.

Far from her village when the conflicts start, Binti hurries home, but anger and resentment has already claimed the lives of many close to her.

Once again it is up to Binti, and her intriguing new friend Mwinyi, to intervene—though the elders of her people do not entirely trust her motives–and try to prevent a war that could wipe out her people, once and for all.

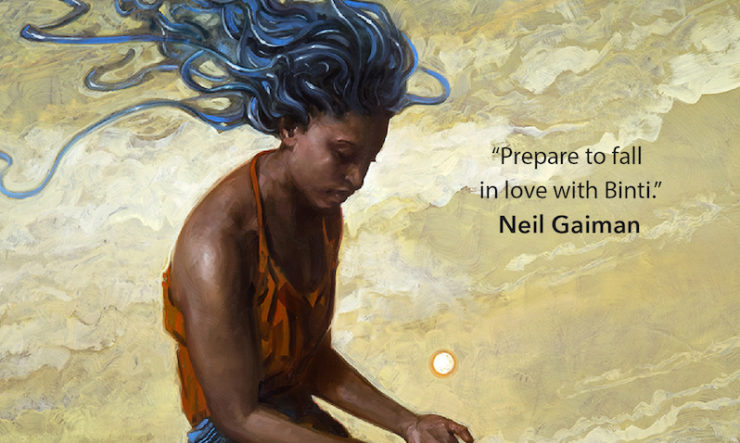

Don’t miss this essential concluding volume in Nnedi Okorafor’s Binti trilogy: Binti: The Night Masquerade, available January 16th from Tor.com Publishing.

Chapter 1

Aliens

It started with a nightmare . . .

“We still cannot get out,” my terrified father told me. His eyes were stunned and twitchy. He was underground. We were in the cellar of the Root, the family home. Everyone was. Covered in dust, coughing from the smoke. But only my father was looking at me. I could hear my little sister Peraa nearby asking in a terrified voice between coughs, “What’s wrong with Papa? Why’s he doing that with his hands?”

Buy the Book

Binti: The Night Masquerade

My perspective pulled back and now I was just looking at it happening. My family was trapped in there. My father, two of my uncles, one of my aunts, three of my sisters, two of my brothers. I saw several of my neighbors in there too. Why was everyone in there in the first place? All huddled in the center of the room, grasping each other, wrapping themselves with their veils trying to hide, crying, tears running through otjize, praying, trying to call for help with their astrolabes. Bunches of water grass, piles of yams, sacks of pumpkin seeds, dried dates, containers of spices sat in corners. Smoke was coming through the fibrous ceiling and walls of the cellar. The old security drone that had stopped working before I was born still sat in the corner covered with its woven mat.

“Where is Mama?” I asked. Then more demandingly, I said, “Where is MAMA?! I don’t see her, Papa.”

“But the walls will protect us,” my father said.

I felt the pressure of his strong hands as he grasped me. They didn’t feel arthritic at all. “The Root is the root,” he said. “We will be okay. Stay where you are.” He brought his face close to mine, then the words appeared before my eyes. Red as blood. “Because they are looking for you.”

“Where is Mama?” I asked again, this time waving my hands in my nightmare, as I clumsily used the zinariya, the activated alien technology in my DNA.

But I was suddenly in the dark, alone with my words, as they floated before me like red desert spirits. Where is Mama? Instead, the sound of hundreds of Meduse thrumming filled my head and the vibration traveled deep into my flesh. Laughter. Angry laughter. I sensed anticipation, too. “Binti, we will make them pay,” a voice rumbled in Meduse. But it wasn’t Okwu. Where was Okwu? . . .

I awoke to the universe. Out here in the desert, the night sky was so bright with stars. It was almost as clear as the sky when I’d been on the Third Fish traveling to and from Earth. I stared up, hearing, seeing, and balanced equations whispered around me like smoke. I’d been treeing in my sleep. It was that bad. I hadn’t even done this while in the Third Fish after the Meduse killed everyone but me. I was having so much trouble adjusting to the zinariya. That wasn’t a just dream about my family, it was also a message sent using the zinariya from my father. I couldn’t awaken fully before receiving it and so my mind protected me from the stress of it by treeing.

Mwinyi and I had left the village on camelback hours ago and then we’d stopped to rest. I’d lain in the tent Mwinyi set up, while he’d gone off for a walk. I was so exhausted, scared for my family, and overwhelmed. Everything around me felt off. Trying to get some sleep had not been a good idea.

“Home,” I whispered, rubbing my face. “Need to get . . .” I stared at the sky. “What is that?”

One of the stars was falling toward me. The zinariya, again. “Please stop,” I said. “Enough.” But it didn’t stop. No. It kept coming. It had more to tell me, whether I was ready or not. Its golden light expanded as it descended and I was so mesmerized by its smooth approach that I didn’t tree. When it was mere yards above, it exploded into showers of brilliance. It fell on me like the golden legs of a giant spider and then the zinairya made me remember things that had never happened to me.

I remembered when . . .

Kande was washing the dishes. She was exhausted and she had more studying to do, but her younger twin brothers had wanted a late night snack of roasted corn and groundnuts and they’d left their stupid dishes. How they’d managed to eat something so heavy this late at night was beyond her, but she knew her parents wouldn’t complain. This was why at the ages of six they were so plump. Her parents never complained about her brothers. Still, if Kande left the dishes for the morning, the ants would come. It was a humid night, so she knew other things would come too. She shuddered; Kande detested any type of beetle.

She finished the dishes and looked at the empty sink for a moment. She dried her hands and picked up her mobile phone. It was already eleven o’clock. If she focused, she could get a good hour of studying in and still manage five hours of sleep. In her final year in high school, she was ranked number six in her class. She wasn’t sure if this was good enough to be accepted into the University of Ibadan, but she certainly planned to find out.

She put her phone in her skirt pocket and switched off the light. Then she stepped into the hallway and listened for a moment. Her parents were watching TV in their room and the light in her brothers’ room was off. Good. She turned and tiptoed to the front of the house, quietly unlocked the door, and sneaked outside. It was a cool night and she could see the open desert just beyond the last few homes in the village.

Kande leaned against the side of the house as she brought out a pack of cigarettes from her skirt pocket. She shook one out, placed it between her lips, and brought out a match. Striking the match with her thumbnail, she used it to light her cigarette. She inhaled the smoke and when she exhaled it, she felt as if all her problems floated away with it—the ugly face of the man her parents said she was now betrothed to, the money she needed to buy her uniform for her school dance group, whether Tanko still loved her now that he knew she was betrothed.

She took another pull from her cigarette and smiled as she exhaled. Her father would be furious and beat her if he knew she had such a filthy habit. Her mother would wail and say no man would want her if she didn’t start behaving, that she was too old for rebellion. Kande was looking toward the desert as she thought about all this and when she first saw them, she was sure that her brain was trying to distract her from her own dark thoughts.

They were a house away before she even moved. And by then, she was sure they’d seen her. Tall, like human palm trees and not human at all. And even in the moonlight, she saw that they were gold. Pure shiny gold. Not human at all. But with legs. Arms. Bodies. Long and thin like trees. Walking slowly toward her in the night. There wasn’t another soul silly enough to be outside at this time of night. Just her.

Kande didn’t know it, but everything depended on those moments after she saw them. What she did. The destiny of her people was in her hands. She stared up at the aliens who saw themselves as one thing but accepted the name of “Zinariya,” (which meant “gold,”) that human beings gave them and . . .

. . . I fell out of the tree. Mwinyi was shaking me. Gusts of sand and dust slapped at my skin when I turned to him and I coughed hard.

“Binti! Come on! Pull yourself out of it!”

At first, I saw all things around me as the sums of equations, numbers splitting and unfurling, falling away, rotating, all in harmony. My eyes focused on his tall lanky frame, his caftan and pants that were blue like Okwu flapped in the sandy wind. Grains of sand blew about pretending chaos, but each arced a trajectory that coincided with those around it. I shook my head, trying to come back to myself. My mouth had been hanging open and I spit out sand.

I twitched as a rage flew into me like an explosion. My family! I thought, frantic. My family! Before I could shout this at Mwinyi . . . I saw Okwu hovering behind him. My eyes widened and my mouth hung open again. Then Okwu was gone. Instead, behind Mwinyi were small skinny red-furred dogs; they ran about flinging their heads this way and that way. I felt one touch my face with its cool black nose, sniffing. It yipped, the sound close to my ear. The dogs were running all around us, at least as far as I could see, which was only a few feet. Our camel Rakumi was roaring with distress. I was seeing words now as Mwinyi desperately tried to reach me using the zinariya.

The floating green words said, “Sandstorm. Dog pack. Relax. Grab Rakumi’s saddle, Binti.”

I am not a follower, but there are times when all you can do is follow. And so yet again, I submitted. This time it was to Mwinyi, a boy I had only known for a few days, of a people I’d viewed as barbarians all my life and now knew were not, my father’s people, my people.

I was breaking and breaking and into that moment I followed Mwinyi. He led us out of that sandstorm.

The sun broke through.

The air cleared of dust.

The storm was behind us.

I sighed, relieved. Then the weight of the sudden quiet made my legs buckle and I sunk to the ground at the hooves of our camel Rakumi. I pressed my cheek to the sand and was surprised by its warmth. There I lay, staring at the retreating sandstorm. It looked like a large brown beast who’d decided to leave, when really it just happened to travel the other way. Churning, roiling, and swirling back the way we’d come. Toward the Enyi Zinariya village. Away from my dying, maybe even dead, family.

I weakly raised my hands and moved them slowly, typing in the air. The various names of my father. Moaoogo Dambu Kaipka Okechukwu. I tried to send it. But they wouldn’t go. I rolled my head to the side in the sand, feeling the grains ground into my otjize-rolled okuoko, blue tentacles layered with sweet-smelling red clay and now sand. I tried to call Okwu. I tried to reach him. To touch him with my mind as I had days ago, now. Again, nothing.

Then I started weeping, as the world around me began to do that expanding thing that it had been doing since we’d left the Ariya’s cavern over a day ago. As if everything were growing bigger and bigger and bigger, though it was still the same. Mwinyi said it was just my body settling with the zinariya technology that Ariya had unlocked within me, but what did that matter? It didn’t make it any better. The sensation was so jarring that I constantly felt the Earth would decide to fling me into space at any moment.

I shut my eyes and it was as if I’d fallen again. Into my other nightmare. The nightmare from a year ago. Now I was back on the Third Fish, sitting at the dining hall table. I could taste the sweet milky dessert in my mouth. My edan was in my hand, the strange gold ball back inside the stellated cube–shaped metal shell; it was whole again. And I was gazing at Heru, the beautiful boy who’d noticed that I’d braided my otjize-rolled locks into a tessellating triangle pattern that reflected my heritage. His granite black hair was falling over one of his eyes as he laughed. He glanced at me, and I smiled. And then his chest burst open and his warm blood spattered on my face and I fled within myself, quivering, silently screaming, breaking. Everyone was dead.

The dining hall grew red, even the air took on a red tint. There was Okwu, behind Heru. I could smell blood, as I tasted the sweet milky dessert in my mouth. Everyone was dead. I had to survive. I slowly got up, clutching the edan in my hand, and when I turned, it wasn’t a Meduse I faced but my cowering family inside the bowels of the Root. In the large room, below, where all the foodstuffs and supplies were stored.

The smell of blood turned to one of smoke. I’d moved from one nightmare to another. My eye first fell on my oldest sister shrieking in a corner as her long, long hair went up in flames. I was coughing and then looking frantically around as I waited to smell the burning of my own flesh because flames were consuming the entire room. Now my family was all around me, my father, siblings, several of my cousins, aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, shrieking, stumbling, thrashing, lying still as they burned. Everyone was burning or already dead.

I whimpered, my flesh feeling too hot. Let me die too, I thought, waiting, hoping, for the burning to intensify. My family. Instead, the fire consuming my family stopped biting me and shrunk away. It calmed. It didn’t stink of burning flesh now. The fire smelled woodsy and the center of it looked like a pile of glowing rubies. Everything undulated and when it resettled, things looked more real, no red tint, so solid and clear that I could touch the dry ground beneath me, warm my hand at the fire before me.

I distantly felt my okuoko writhing with anger. I reached up, grasping them, trying to calm their wriggling. All this was confusing me. I was just coming out of flashbacks of the deaths of my friends and family and now the zinariya was forcing history on me again . . .

The old man was named Takeagoodposition. He stood before five other old men, holding a slender pipe to his lips. The smoke smelled sweet and thick and when it blended with the smoke from the fire, it smelled awful.

“The child is a dolt,” Takeagoodposition said. “Kande is one of those girls who would follow a lion to her death if it flashed a pretty grin.”

The men in the group all laughed and nodded.

“No, we won’t put the community in the hands of a girl; how would we look?”

“But they came to her first,” a tall man said, his long legs crossed before him. “And let’s be honest, if those things had come to any of us, what would we have done? Fled? Fainted? Tried to shoot them? But she somehow learned to speak with them, gained their trust. ”

“Look what it cost her,” the only woman in the group said. “She is like a girl possessed, seeing things that are not there.”

“My grandson said it was like they put alien Internet in her brain,” another elder said.

There was more soft laughter.

Takeagoodposition frowned deeply. “None of that matters now,” he snapped. “The Koran says to be kind and open to strangers. Let us welcome them. The girl will introduce us and we will take over.”

“Have you seen them?” another of the men asked. “They’re beautiful, especially in the sun.”

“And probably worth millions if we divide them into coinage,” someone remarked.

Laughter.

“These Zinariya, they are aliens,” Takeagoodposition said. “We’ll be cautious.”

It was as if I were sitting with the men and woman. Listening to them talk about the Zinariya. Some movement behind a cluster of dry bushes caught my eye and I was sure I saw someone slowly back away and then run off.

“Kande,” a woman’s voice said. It seemed to come from all around me. “She did well, for a child who liked to smoke.”

I frowned, wanting to stop all this nonsense and scream, “What does smoking have to do with aliens?!” But then I saw something bouncing around within the circle of people. A giant red ball. It disappeared in the swirls of dust and then bounced back on the ground. It rolled up to me and flattened, shaped like a red candylike button embedded in the sand.

I stared at it.

“Press it.” The words appeared in front of me in neat and careful green and then faded like smoke. Mwinyi was speaking to me through the zinariya.

I smashed the button with my fist, vaguely feeling the button’s hardness. I heard a soft satisfying click. Everything went quiet. Nothing but the sound of the soft wind rolling across the desert. I rested my forehead on the sand, weeping again.

“Can you get up,” Mwinyi asked, kneeling beside me. “Has it stopped?”

I raised my head and looked up at him. His bushy red-brown hair was coated with sand and the long lock that grew in the back of his head was dragging on the ground beside my knee, collecting more sand. The world behind him, the blue sky, the sun, started expanding again. But not as badly as before, nor was I seeing the death of everything I loved. But I knew of it.

I opened my mouth and screamed, “Everyone’s dead!” I rolled to the side, grinding the other side of my head into the sand. My face to the sand, feeling its heat on my skin and blowing out sand, I wailed, “MY FAMILY!!!! I DIE! EVERYTHING IS DEAD! WHY AM I ALIVE?! OOOOOOH!” I sobbed and sobbed, curling in on myself, shutting my eyes. I felt him press a hand to my shoulder.

“Binti,” he said. “Your family—”

“DON’T! LEAVE ME ALONE!”

I heard him angrily suck his teeth. Then he must have walked away.

I don’t know how long he left me there, but when he pulled me to a sitting position, I was too defeated to fight him. I slumped there, the hot sun beating down on my shoulders.

He sat across from me, looking annoyed.

“I don’t have a home anymore,” I said. I felt my okuoko writhe on my head.

“Ah, there’s the Meduse in you,” he said.

“I am Himba,” I snapped.

“Binti, they might be alive,” Mwinyi said. “Your grandmother back in my village communicated with your father in Osemba.”

I stared at him, shuddering as I tried to hold back the flash of rage that flew through me. I couldn’t and it burst forth like Meduse gas. “I saw them trapped . . . I SAW THEM!” I shouted. “I smelled them b-b-burning!”

“Binti,” he said. “Remember, you’ve just been unlocked! And you have that Meduse blood. I’ve heard you whimpering in your sleep about what happened last year on that ship. And we’re out here in this desert, exhausted and far from your home. You’re all mixed up. Some of what you see is communication, some is probably the zinariya showing you stuff it wants you to know, but some is delusion, nightmare.”

I raised a hand for him to be quiet and rested my chin to my chest; I was so exhausted now. Tears spilled from my eyes. Everything I’d seen was so real. “I don’t know anything,” I softly said.

I felt Mwinyi looking at me. “Your father said the Khoush came after Okwu,” he said. “They don’t know what happened.”

“Who is ‘they’?” I asked.

“Your grandmother and father. As I’m sure you know, your Okwu is a small army in itself. Your family took shelter in the Root when the fighting began.”

“So they are in the cellar,” I muttered. “That part is true.”

“Yes.”

I had to process the idea that my father had spoken with my grandmother through the zinariya. “When?” I asked. “When did he talk to her?”

“Just after you were unlocked.”

“Just after I sensed Okwu was in trouble,” I said. “So he could be—”

“I don’t know, Binti. We don’t know. Sometimes when the zinariya communicates, it disregards time. We’re going to find out.”

“You could have told me hours ago.”

Mwinyi paused, his lips pursed. “They told me not to. They didn’t think the news would help you.”

When I said nothing to this, he said, “If you want to get home to help, we can’t waste time like this.”

I glared at him.

“Don’t give me that look,” he said. “Aim your Meduse rage that way.” He pointed ahead of us. “Last night, I thought I was free to do whatever I wanted. Instead, I’m here, taking you to what can’t be a place of peace. And I do care about your family; I’m doing my best.”

I ran my hand down my face, wiping away tears, sweat, snot. I paused, realizing I’d probably also just wiped a lot of my otjize from my face too. I sighed, flaring my nostrils. Everything was so wrong. “You don’t have to take me anyw—”

“I do and I will,” he said. “You want to know what I think?” He looked at me for a moment, clearly trying to decide if it were better to keep his words to himself.

“Go on,” I urged him. “I want to hear this.”

“You try too hard to be everything, please everyone. Himba, Meduse, Enyi Zinariya, Khoush ambassador. You can’t. You’re a harmonizer. We bring peace because we are stable, simple, clear. What have you brought since you came back to Earth, Binti?”

I stared nakedly at him, the hot breeze blowing on my wet face felt cool. My okuoko had stopped writhing. I felt deflated. “I need my family,” I said hoarsely.

He nodded. “I know.”

I grabbed the sides of my orange-red wrapper as I looked straight ahead, toward where we were to go. Right before my eyes, the world seemed to expand, while staying the same, as if reality were breathing. It was a most disconcerting sight. I let myself lightly tree, as I took in several deep breaths. “Everything is . . . still looks as if it’s growing,” I said. I looked directly at him for the first time. “I . . . I know that sounds crazy, but that’s really what I’m seeing.”

Mwinyi frowned at me, twirling his long matted lock with his left hand, two of the small brown wild dogs sitting on either side of him like soldiers. Then he said, “I can get you home, but I don’t . . . I don’t know how to help you, Binti. I never needed to be ‘activated’; I don’t even know what you’re going through.”

I clutched the front of my orange-red top and whimpered, thinking of my family back in Osemba. After traveling all day, then through the night, we’d traveled much of the next day. When the sun was at its highest, we’d settled down in our tent for some rest. We’d finally fallen asleep when the sandstorm hit. “I know you think I’m too much but—”

“That’s not what I said.”

I cut my eyes at him. “You did. Don’t worry, it’s not the first time something like this has happened to me,” I said, shutting my eyes for a moment. When I opened them, I felt a little better. “Let’s keep going. We can travel through the night again.”

When I tried to get up, he quickly stood and said, “No. Rest.”

“I’m okay,” I said. “Just give me a minute and we can go as soon as—”

“Binti, we stop. You have to rest. The zinariya is—”

“But if they’re in the cellar . . .” I started shaking again. I wrung my hands, my heart beating fast.

“Whatever is happening there, we can’t stop it,” he said.

I tried to get up and he put a hand firmly on my shoulder. I wanted to fight him, but the feeling of vertigo was back and I could only roll to my side in the dirt, shuddering with misplaced outrage, my okuoko writhing, again.

“We’re making fast time, but we’re still a day away,” he said. “Binti . . . Calm down. Breathe.”

“Even with the wild animals out here? The slower we go, the more we risk—”

“Wild animals don’t scare me,” Mwinyi flatly said, looking me so deeply in the eyes that everything around me dropped away. My okuoko slowly settled on my shoulders and down my back. The Meduse rage, which I was still learning to control, left me like cool air flees the morning sun. There is nothing like gazing into the eyes of a harmonizer when you are also a harmonizer.

We stayed and without further exchanging words, we set up camp. I was glad when he walked off into the desert for an hour to see if he could find anything fresh to eat, the small pack of dogs following him like curious children. I needed the quiet. I needed to be alone with . . . it.

“It’s not something to learn,” he said, over his shoulder. “It’s part of you now. Intuit it.”

And that I understood. I sat on the woven raffia mat in the open tent. I had been studying my edan for over a year—a mysterious object I’d found in a mysterious place in the desert, whose purpose I did not know, and whose functions I had first learned of by accident. An object that had saved my life, been the focus of my major at Oomza Uni, and was now in about thirty tiny triangular metal pieces and a gold ball in my satchel. Yes, I understood intuiting things.

I brought up my hands and used the vague virtual device that rose before me to type out Mwinyi’s name and the word “Hello” in Otjihimba. Then I envisioned Mwinyi, who was most likely on the other side of the sand dune he’d disappeared over. Before I saw him in my mind, I felt his nearness, his alertness. He was monitoring me, even from where he was; I wasn’t just guessing this, I knew it for a fact. His response appeared before me in green letters that were a different style from mine, neat but relaxed and in Otjihimba, “Are you alright?”

“Yes,” I responded.

Then, yet again, I tried to reach my father. “Papa,” I wrote. I tried to push the red letters as I held my father’s image in my mind. It was as if the words were fixed onto a wall, I couldn’t send or even move them. I waved my hands and the words disappeared. I tried another five times before giving up, growing increasingly more agitated, the letters looking sloppier and sloppier. I wiped tears from my cheeks and then before my mind started going dark again, I tried reaching out to Okwu. Five times. Again, nothing.

I rubbed my eyes and when I looked at the backs of my hands, for the first time in hours, I realized that they were nearly free of otjize. I gasped, touching my face, looking at my arms, my legs. The sand from the storm had stripped most of it away. Mwinyi had said nothing about this, or maybe he hadn’t noticed. I felt like shrieking as I fumbled with my satchel. I had about half a jar left. When I’d arrived on Earth, I’d assumed I would have time to make more.

I gazed at the jar. The red paste wasn’t as rich as the one I could make from the clay I dug up around the Root. It was otjize different from any otjize made by a Himba girl or woman. Mine was from a different planet. I held it to my nose and sniffed its rich scent and saw the tall trees of the forest where I collected the clay, the piglike creature who foraged in the bushes. I saw the faces of Professor Okpala, the large pitcher plants that grew beside the station, my classmates, like Haifa and Wan. However, I also saw the Root. And the faces of my family, the dusty roads of Osemba and its tranquil lake.

Rubbing it onto my face, I looked out at the desert. Dry, expansive, free. I inhaled deeply, to control my breathing. No more tears that would wash away the otjize I’d just put on my face. And I did what I’d unconsciously done with my edan on the Third Fish, but this time instead of speaking to my edan, I spoke to the zinariya. And it answered. It was gentle and kind, but I didn’t have the unaffected fresh mind of a baby. I was seventeen years old, the second youngest child in my family who’d been tapped to be my community’s next harmonizer. I’d instead chosen to leave Earth and go to Oomza Uni and nearly died for my choice. I’d lived and then learned, so much. To engage with the zinariya was to overwhelm all my senses. In the distance, I saw a yawning black tunnel swallowing the soft light of the setting sun.

I don’t know what happened.

Mwinyi returned an hour later carrying two dead rabbits. He found me lying on the mat, saliva dribbling from the side of my mouth. I’d watched him approach through dry gummy eyes. As I gasped his name and weakly typed it on the virtual device now hovering on my lap, I saw the red word appear before me. His name floated above him, slowly descending onto his head, where it settled and oozed onto him like melted candle wax. I groaned and when I did, I saw the phonetic spelling of the sound creep from my mouth onto the sand like a caterpillar. It was as if the zinariya itself was mocking me.

It was all too much and when I tried treeing to make it better, my world filled with so many numbers that I felt as if I’d kicked a hornet’s nest. I couldn’t see around me and some of the numbers grew more aggressive the angrier I got, zooming around and darting at me.

“How am I supposed to get up tomorrow?” I whispered. “So I can . . . my family.” I started weeping, though I knew it would wash off even more of my otjize. I turned away from Mwinyi, repulsed by the thought of him seeing me so naked. One of the wild dogs trotted up to me and sniffed my okuoko. I heard Mwinyi put the two large rabbits he’d caught down and I assumed the soft yipping I heard was him telling the dogs not to touch the rabbits.

“Can you see?” he asked.

“No,” I said.

He clucked his tongue with annoyance. “Get up, Binti.”

“I can’t.” I started crying harder. Then I thought about my otjize and my crying turned to sobs. I felt another of the dogs sit on me and I heard Mwinyi walk away. Then I must have fallen asleep because when I woke, I smelled cooking meat. My stomach rumbled and slowly I sat up. The dog who’d sat on me had also apparently fallen asleep and now it lazily stepped off my legs.

I looked around. My world was stable. No expanding, no numbers, no words bouncing, crawling, oozing about with every sound I made. No tunnel in the distance. No feeling like the Earth would hurl me from its flesh into space. I sat back with relief. It was a dark night, the sky overcast with thick clouds. Our camel Rakumi was resting nearby, her saddle on the ground beside her. Mwinyi sat before the fire he’d built, eating. In the darkness, the fire was a welcome beacon. I stood up and then hesitated.

“I’m not Himba,” he said, without looking away from the fire. “Your otjize looks like adornment to me. You don’t look naked. Come and eat. We’re not staying here long.”

Regardless, as I crept up to him, I burned so hot with embarrassment that I could only approach walking sideways. I sat right beside him. This way, he’d have to make more of an effort to look at me. When I looked up, I noticed the dogs lying on top of one another on the other side of the fire, a pile of small bones beside them.

“Aren’t they wild dogs?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said.

“So why are they still here?”

He shrugged. “The fire’s warm and they like me.” He turned to me. Surprised by his sudden look, my eyes grew wide and I crossed my arms over my chest and instinctively tried to pull my head into my top. It was such a silly thing to do that he grinned and laughed. I found myself smiling back at him. He had a nice smile.

He turned back to the fire and said, “And I gave them one of the rabbits I caught.”

I laughed, again.

“We made an arrangement,” he continued. “I feed them and they stay and stand guard for a few hours while you and I get more sleep.”

“They told you this?”

He nodded. “Wild dogs are free and playful, once you convince them not to attack you,” Mwinyi said. “I suspect we have until their bellies have settled and our fire dies down. I don’t think there are many other dangerous animals out tonight. But Binti, something’s clearly happening in your homeland . . . and maybe not just in your homeland.”

And what if it’s because of me? I thought. Maybe he was thinking it too because he was quiet and pensive and for several minutes neither of us spoke.

I changed the subject. “My best friend Dele . . . well, he used to be my best friend,” I said, gazing into the fire. “Now, I don’t think he’s a friend at all.”

“Sorry to hear that,” Mwinyi said.

“It’s okay,” I said. “I think I lost all my friends when I left, really.” We were silent for a moment. I continued, “Dele was always interested in the old Himba ways. He knew everything. He was always reminding me that the Himba see fire as holy. A medium to communicate with the Seven. What was the name . . . okuoko, holy fire. Yes, that was it.” I sighed, the warmth of the fire toasting my legs and face. “During Moon Fest, I’d sit beside Dele with the other girls and boys. While everyone else sang, I wanted to dance in front of the fire because I always thought the Seven preferred dance and numbers to singing. After I was tapped to be master harmonizer, Dele said I would be disgracing myself if I danced.” I frowned. When I’d last spoken to him, he’d been apprenticed to train as the next Himba chief; he’d looked and spoken to me as if I were a lost child.

“To us Enyi Zinariya, fire is holy too,” Mwinyi said.

Something large and green zipped past my ear, zoomed a circle over the fire, and then plunged into it. There was a small burst of sparks and a soft paff!

“What was that?” I said, jumping up.

“Sit,” Mwinyi said. “And watch.”

I didn’t sit. But I watched.

A second later what looked like an orange, yellow, red spark the size of a tomato flew from the flames, shooting straight up into the black night sky. Then it silently went out.

“I thought you’d spent time in the desert before,” he said.

“Only during the day.”

“Ah, that explains why you’ve never seen an Icarus,” he said. “They’re large green grasshoppers who like to fly into fires. Then they fly out of the flames and to dance with their new wings of fire and fall to the ground wingless. The wings grow back in a few days. Then they do it again. The zinariya says that some woman genetically engineered them as pets long ago.”

I looked around for the wingless grasshopper. When I saw the creature, I ran to it. I picked it up and held it to my face. It smelled like smoke. “Ridiculous,” I whispered as it jumped from my hand to the sand and hopped wingless into the darkness.

“Can . . . can you harmonize with them? Ask them why they do it?” I asked, coming back to the fire.

“Never bothered. I doubt they know why they do it, really. It’s how they were programmed by science, I guess.”

“Well, maybe,” I said. “But I’m sure they rationalize it somehow.”

“True. I’ll ask one someday.”

I sat down at my spot and as I did, he moved his hands before him and then asked, “How are you feeling?”

“Who wants to know?” I asked.

“Your grandmother.”

“Why doesn’t she ask me?”

He cocked his head and laughed. Then moved his hands again. Moments later, my world began to expand and I shrieked. The words came at me like a cluster of beasts zooming from the depths of the desert. I thought they were going to smash into me, so I raised my hands to protect myself. Bright like sunshine the words read, “ARE YOU ALRIGHT?”

“Okay,” I whispered, still hiding behind my raised hands. “Tell her I am okay.”

The words receded, but my world did not stop expanding. I touched the ground, grasping sand with my fists and digging my feet into the cool sand. I felt better.

“Ariya says don’t try to use the zinariya except with me,” Mwinyi said. “Give it about a week. You have to ease into it or it’ll make you really ill. Focus on what’s ahead more than what’s behind, for now.”

I nodded, rubbing my temples.

“Do you want to hear how I learned I was a harmonizer?” he asked, after a moment.

I nodded, digging my fingers and toes deeper into the sand. Anything to take my mind from the terrible feeling of leaving the Earth.

“When I was about eight years old—”

I gasped. “I was eight when I found my edan!” I said. “Is that when you—”

“Binti, I’m telling you the story of it. Just listen.”

“Sorry,” I said, wishing everything would stop undulating.

“So, when I was eight, I walked out into the desert,” he said. “My family was used to me doing this. I never went far and I only went during the day, in the mornings. I would walk until I could not see or hear the village.”

I smiled and nodded, the thought taking my mind off my rippling world a bit. I, too, had loved to walk into the desert when I was growing up. Even though I was never supposed to. And doing so changed my life.

“This day, I was out there, listening to the breeze, watching a bird in the sky. I unrolled my mat and sat down on a patch of hardpan. It was a cloudy day, so the sun wasn’t harsh. They came from the other side of a sand dune behind me, or maybe I’d have seen them. I hadn’t heard them at all! They were that quiet. Or maybe it was something else.”

“What? What were ‘they’?” I asked. “Another tribe?”

He nodded. “But not of people, of elephants.”

My mouth fell open. “I’ve never seen one, but I hear they hate human beings! The Khoush say they kill herdsmen and maul small villages on the outskirts of—”

“And they always kill every human being they come across, right?” he asked, laughing.

I pressed my lips together, frowning, and unsurely said, “Yes?”

“Because I’m actually a spirit,” he said.

I shivered at his words, thinking, Is he?

Mwinyi groaned. “Haven’t you learned anything from all this? What’d you think I was a few days ago? What did you think of all Enyi Zinariya?” I didn’t respond, so he did. “You thought we were savages. You were raised to believe that, even though your own father was one of us. You know why. And now I’m sitting here telling you how I learned I was a harmonizer and you’re so stuck on lies that you’d rather sit here wondering if I’m a spirit than question what you’ve been taught.”

I sighed, tiredly, rubbing my temples.

Mwinyi turned to me, looked me up and down, sucked his teeth, and continued, keeping his eyes on me as he spoke. Probably enjoying my discomfort with his gaze. “They rushed up to me,” he said. “The biggest one, a female who was leading the pack. She charged at me. When you see elephants coming at you as you sit in the middle of the desert . . . you submit. I was only eight years old and even I knew that. But as she came, I heard her charge, ‘Kill it! Kill it!’ I looked up and I answered her. ‘Why?!’ I shouted. She stopped so abruptly that the others ran into her. It was an incredible sight. Elephants were tumbling before me like boulders rolling down a sand dune. I will never forget the sight of it.

“When they all recovered, she spoke to me, again, ‘Who are you? How are you able to speak to us?’ And I told her. And I told her that I was alone and I was a child and I would never harm an elephant. The others quickly lost interest in me, but that one stayed. She and I spoke that day about tribe and communication. And for many years, we met there when the moon was full, as we agreed. A few times we met when I needed her advice, like when my mother was ill and when I quarreled with my brothers who were bigger and older than me.”

“What of your sisters?”

“I don’t have any,” he said. “I’m the youngest of six, all boys.”

“Oh,” I said. “That’s strange.”

“What’s stranger is that I’m the only one who doesn’t look like he could crush stone with his bare hands,” he said, smiling ruefully. “Even Kam, who’s a year older than me, just won the village wrestling championship.”

I laughed at Mwinyi’s outrage.

“Anyway, during these times, when it wasn’t a full moon, I was able to call Arewhana, that was her name, from far away. She taught me how to do it. It was something she said I could do with larger, more aware animals like elephants, rhinos, and even whales if I ever ventured to the ocean.

“Arewhana taught me so much. She was the one who told me I was a harmonizer. And she was the one who taught me how to be a harmonizer. Elephants are great violent beasts, but only because human beings have treated them in a way that made using violence the only way for elephants to survive. There are many elephant tribes in these lands and beyond.”

An elephant had taught him to harmonize and instead of using it to guide current and mathematics, she’d taught him to speak to all people. The type of harmonizer one was depended on one’s teacher’s worldview; I rolled this realization around in my mind as I just stared at him.

Mwinyi’s bushy red hair was still full of dust and sand and he didn’t seem to mind this, but his dark brown skin was clean and oiled. I’d actually seen him rubbing oil into his skin earlier. I knew the scent. It was from a plant that grew wild in the shade of palm trees and some women used it to flavor desserts because it tasted and smelled so flowery. He carried some in a tiny glass vial he kept in his pocket. A few drops of it went a long way. The oil protected his skin from the desert sun in a way quite similar to otjize, and it brought out its natural glow. I wondered if this plant smell had also set the elephants at ease.

I chewed on this thought, while gazing at Mwinyi. My world had stabilized again.

As I settled on the mat in the tent, I could hear Mwinyi moving about outside while he softly yipped and panted. I watched as the wild dogs got up; soon our tent was surrounded by the group of about eight dogs. None of them slept now; instead they sat up and watched out into the night like sentries.

Mwinyi came into the tent and lay beside me. “Better sleep now,” he said. “I think we have about three hours of safety at most. Then they’ll leave and if there are hyenas or bigger angrier dogs out there, those can sneak up on us.”

He didn’t have to tell me twice. Sleep stole me away less than a minute later.

Excerpted from Binti: The Night Masquerade, copyright © Nnedi Okorafor, 2018