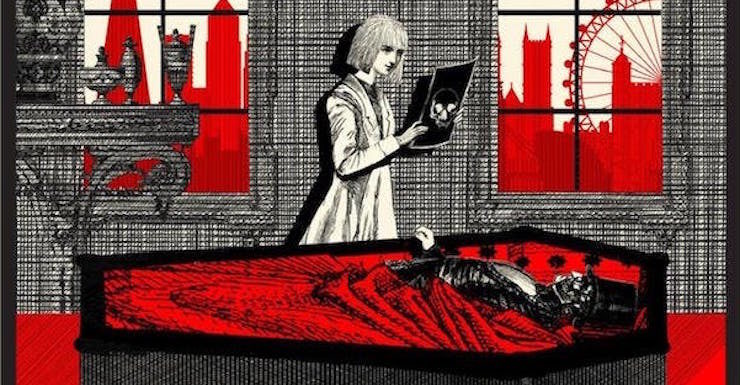

For this week’s column, Vivian Shaw—author of Strange Practice (Orbit, 2017)—has generously agreed to answer some questions. It’s not everyday you get an urban fantasy whose protagonist is a doctor for monsters, so I have been a little bit intrigued to learn more.

LB: Let’s start with a basic question. Strange Practice’s main character is a doctor who operates a clinic specialising in “monsters”—from mummies and vampires to ghouls and banshees. What’s the appeal of having a physician for an urban fantasy protagonist?

VS: Partly it’s because I love writing clinical medicine. I wanted to be a doctor way back in the Cretaceous but never had the math for it, and I read medical textbooks for fun, so getting to come up with a whole new set of physiologies and the consequent diseases is an endless source of pleasure. Storywise—it’s competence porn. Watching a doctor do what they’re good at is exciting the way watching a lawyer argue or a pianist play is exciting to me, and I love being able to put that kind of easy I-got-this expertise into my books. It’s deeply satisfying to write about people doing things I can’t actually do myself.

Buy the Book

Strange Practice (A Dr. Greta Helsing Novel)

Having the main character be a physician also allows her to learn all sorts of information she might never otherwise have encountered; the scientist in her is fascinated with problem-solving, the pragmatist interested in how to fix the situation, the clinical observer in gathering data and filling up the memory-banks for later reference. And because I am the kind of person who makes organizational charts for their fictitious infernal civil service (color-coded by division and branch!) I’ve always been more interested in the monsters than the heroes who hunt them. It was much more fun to have my protagonist attempt to fix undead blood-sucking fiends than to run around after them with a stake and garlic and snappy one-liners.

In a lot of ways the book is about found family, but it’s also about what it means to be a person, even if that person happens to be technically not a human. Through the lens of Greta’s perceptions and worldview, because her job is to care for people whatever shape they might be, we get a different viewpoint on the nature of good and evil.

LB: It seems that vampires are peculiarly prone to melancholia! I note that the vampires Greta encounters have made an appearance or two in literature before, although they are not as well known as say, Dracula or Carmilla. What was most fun about reimagining these characters for Strange Practice?

VS: Getting to borrow characters from classic vampire lit is one of the most enjoyable parts of this series. Originally, the book that would become Strange Practice had as its big idea “let’s see how many characters from classic horror literature I can get into one story,” and in that version both Dracula and Carmilla had significant screen time; I ended up cutting them for the story’s sake, but they do still exist in this universe—they might make it into the series one way or another. For all of the borrowed characters, the question is the same: who are they, what do they want, how are they described in the source material and how much of that is a function of the historical context—or how much of it can slide directly into the modern day without much adjustment. I think anyone who’s going to do this sort of thing first has to actually like the characters they’re using, or at least understand them fairly well, in order to keep the character recognizable in a new setting. I’m good at it because I have a hell of a lot of experience writing fanfic: that’s what fic is, taking a character or setting that already exists, examining them in and out of context, determining what it is about that character or setting that you find particularly fascinating or compelling, and then writing them—and writing about them—in a new way.

For Ruthven, who doesn’t have a first name in Polidori’s The Vampyre—and who in my version is endlessly salty about both the libelous content of the story and Polidori’s taxonomy, he’s a vampire with an I not a Y—what I had to go on was that the original character as first described is attractive, aristocratic, fascinating, mysterious, popular with the ladies, and a jerk. This is fairly standard central-casting vampire stuff; what I found of particular interest is the fact that he’s apparently a member of society, attending parties and going to and fro about the world, walking up and down in it, traveling abroad with a priggish young companion, with none of the nocturnal sleeps-in-a-coffin limitations. Polidori’s Ruthven demonstrates the peculiarity of being resurrected by moonlight, which is less common, but coincidentally shows up in Varney as well. For my version of Ruthven I kept the member-of-society and cut the moonlight; I wanted that to be a trait associated with Varney’s specific and rarer subtype of sanguivore.

Sir Francis Varney has more backstory, because his authors were paid by the word, or possibly the pound. Varney the Vampyre, or The Feast of Blood (the spelling varies between editions, as far as I can make out, and I went with vampyre-with-a-Y for taxonomical reasons) is a penny-dreadful by the euphonious duo of James Malcolm Rymer and Thomas Peckett (or Preskett) Prest, published in serial form between 1845 and 1847. It’s one of the first examples of vampire angst in the canon: unlike Ruthven (1819) and the much later Carmilla (1871-72) and Dracula (1897), none of whom seem particularly mournful about their lot as hideous monsters who prey on the living and can never hope for the grace of heaven, Varney rarely shuts up about it. He is described as constitutionally melancholy, and physically unprepossessing—again, unlike the other big names in classic vampire lit, who tend to be either sexy or impressive or both—and as having eyes the color of polished tin. The only beautiful thing about Varney is his “mellifluous” voice. Where Ruthven is socially adept and extremely good at manipulating people, Varney is both old-fashioned and awkward, and also casually murderous from time to time.

I had an enormous amount of fun working out what these characters might be like in the modern day—and in particular I enjoyed lampshading the classic-horror-lit angle: they know about the books in which they feature, ostensibly their own origin stories, and generally disagree with them. Unofficial and un-approved biographies get so much wrong.

LB: Apart from the vampires, there’s a number of other people with… mythological? backgrounds in Strange Practice, to say nothing of the strange cult that’s killing people. Do you have a favourite? And will we be seeing more different kinds of “monster” in future books?

VS: Absolutely the mummies. They’re Greta’s favorite and mine as well, because of the very specific logistical challenge of reconstructive surgery and preserved-viscera teletherapy. How do you rebuild someone who’s been missing significant parts of themselves for three thousand years? How do you treat someone for tuberculosis when their lungs are not inside them but over there in a very nice alabaster jar? How do you balance the metaphysical and physical aspects of individuals who exist in the physical world because of metaphysics? The third book is set in a high-end mummy spa and resort in the south of France, where Greta will be spending a few months as interim medical director, and I cannot wait to get stuck in to some of the details I’ll be writing about. Doing the research for that one is going to be entertaining.

I had a lot of fun with the ghouls as well—ritual cannibalism and tribal structure and having to live a completely secret life in the interstices of the modern world—but the mummies are the creatures I love best.

LB: In Strange Practice we heard about Greta’s (not very numerous) co-workers at her clinic and colleagues in the field of unusual medicine, although we didn’t see very much of them. Since Greta will be working as a medical director at a spa in book three, I take it we may see more of said colleagues in coming books? Can you tell us a little about that?

VS: The field of supernatural medicine is necessarily somewhat secretive, which means that the majority of practitioners are themselves in some way supernatural; Greta, as a bog-standard human, is something of an outlier. The conference she attends in Paris in book two is booked and scheduled under a false title—pretending to be a meeting about some incredibly boring and esoteric subspecialty of ordinary medicine—and the mummy spa itself, Oasis Natrun, is on the books as a very private and exclusive health resort that does not anywhere mention in its legal paperwork the fact that it caters to the undead. It’s all very hush-hush.

The director for whom Greta is stepping in is Egyptian mummy specialist Dr. Ed Kamal, also a human: they’re the kind of friends who see each other every four or five years, but exchange cards at holidays. They got to know one another when Greta was beginning to get really interested in restorative and reconstructive techniques, back when her father was still alive and running the Harley Street clinic, and it’s kind of a dream come true for her not just to visit Oasis Natrun but actually get to work there. I love coming up with in-world details like the articles she’s written or is reading, the titles of papers given at conferences, that kind of thing.

LB: So what’s Greta’s favourite paper (or article) that she’s given? Is it different to your favourite one of hers? (I’m assuming you have favourites here.)

VS: Greta’s introduction to Principles & Practice of Internal Medicine in Class B Revenant, Lunar Bimorphic, and Sanguivorous Species (Fourth Edition) and a case study: Occult toxicity of human blood: two examples of poisoning in sanguivores (Type I).

[editorial note: Vivian Shaw provided me with texts of these articles, and I can confirm that they’re fascinating. Here below are the respective first paragraphs of each:]

- “This volume is intended to serve as a handbook for the supernatural physician who is already conversant with the main physiological specifications and peculiarities of the three most-commonly-encountered species; for a basic introduction to supernatural physiology, see Winters and Bray’s Anatomy and Physiology of the Hemophagous Species (note that previous to the Gottingen Supernatural Medicine Symposium of 1980 the term ‘hemophagous’ was used, but ‘sanguivorous’ is the accepted modern terminology); Liu’s Lunar Bimorphic Physiology, second edition; and Papanicolau’s The Mummy: An Overview.”

- “Poisoning in the sanguivorous species largely limits itself to allium-related compounds. Unlike the were-creatures, there is no acute reaction to silver and silver alloys (see Brenner, 1978, foran example of secondary argyria in the classic draculine vampire), and the variety of recreational substances likely to be present in human blood offer only transient effects. Symptoms of acute poisoning in the sanguivore, in the absence of known contact with allium, are therefore to be taken seriously. I hereby describe two cases of poisoning in which the cause of the symptoms was not initially evident.”

LB: I’ve spent most of my time asking you about Strange Practice and Greta Helsing. But I have a feeling that you won’t stick to one genre, or one subgenre in your career. When you take a little break from Greta and co., what do you see yourself writing?

VS: There’s several things I’m looking forward to working on, actually. I’ve been playing about with short stories (my first-ever will be coming out next year from Uncanny, hard sci-fi horror, and I have another one about practical necromancy and air-crash investigation out on submission right now), and there’s a popular history of the space program I want to write; there’s a romance/space opera cowritten with my wife, which we’ll eventually have time for sometime in our lives; and the most exciting for me is the prospect of getting a chance to write the space-station medical procedural/political thriller novel that’s been kicking around in the back of my head for years now.

LB: We’ve talked quite a bit about your work, but to wrap up, let me ask you what about what you read (or write) for fun? What have you read (or written: I know you have a prolific fanfic career) that you’d recommend to the readers of the Sleeps With Monsters column, and why?

VS: The thing about writing books is that while you are in the middle of doing it you have very limited time in which to read them, and for me when I don’t have much time or available brainspace I always go back to re-read things I know I already love, rather than putting forth the intellectual and emotional effort to get into something completely new to me. I have several authors whose works I practically know by heart by now and still enjoy re-reading them every single time: Pratchett, King, Barbara Mertz in her various incarnations are all brain candy for me, and so are my mummy research books. The familiarity with the text is like putting on a pair of gloves that fits perfectly, or settling at a table in your favorite cafe: a return to a known other.

What I write for fun these days is generally love stories about villains getting to be capable, which is sort of the same thing as sensible monsters. The Star Wars fic series all that you love will be carried away (apologies to King for borrowing the title) is probably the best thing I’ve ever done, and it’s not finished yet; for less villainous but more post-apocalyptic adventure (in a world which has moved on) there’s the Mad Max fic Under the Curve, also unfinished; and some of my most satisfying work has been set in the MCU—the completed Captain America stories Waiting for the Winter and the much shorter i’ve been hurt, and we’ve been had and living just like you, living just like me are different ways of approaching the concept of finding oneself again after a very long time out in the cold. That much is a running theme in both my original and transformative work, the idea of characters all at once finding and being found, wanting and being wanted, and the vast enormity of the worlds that open up when two people come together and make something new.

There’s a line in Joan Vinge’s The Snow Queen which says it much better than I can: thou makest me valued feel, when I wind-drift am; when I lost have been, for so long—and a line from Anais Mitchell’s exquisite musical Hadestown that echoes it: I’ve been alone so long/I didn’t even know that I was lonely/Out in the cold so long/I didn’t even know that I was cold … all I’ve ever known is how to hold my own, but now I want to hold you too. In the end I think that’s what a lot of us write about, because it’s such a shared and fundamental human experience.

LB: Thank you.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, is out now from Aqueduct Press. Find her at her blog, where she’s been known to talk about even more books thanks to her Patreon supporters. Or find her at her Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council and the Abortion Rights Campaign.