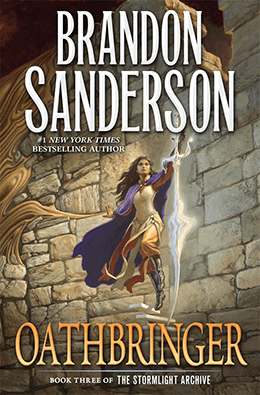

Start reading Oathbringer, the new volume of Brandon Sanderson’s Stormlight Archive epic, right now. For free!

Tor.com is serializing the much-awaited third volume in the Stormlight Archive series every Tuesday until the novel’s November 14, 2017 release date.

Every installment is collected here in the Oathbringer index.

Need a refresher on the Stormlight Archive before beginning Oathbringer? Here’s a summary of what happened in Book 1: The Way of Kings and Book 2: Words of Radiance.

Spoiler warning: Comments will contain spoilers for previous Stormlight books, other works that take place in Sanderson’s cosmere (Elantris, Mistborn, Warbreaker, etc.), and the available chapters of Oathbringer, along with speculation regarding the chapters yet to come.

Chapter 22

The Darkness Within

I am no philosopher, to intrigue you with piercing questions.

—From Oathbringer, preface

Mraize. His face was crisscrossed by scars, one of which deformed his upper lip. Instead of his usual fashionable clothing, today he wore a Sadeas uniform, with a breastplate and a simple skullcap helm. He looked exactly like the other soldiers they’d passed, save for that face.

And the chicken on his shoulder.

A chicken. It was one of the stranger varieties, pure green and sleek, with a wicked beak. It looked much more like a predator than the bumbling things she’d seen sold in cages at markets.

But seriously. Who walked around with a pet chicken? They were for eating, right?

Adolin noted the chicken and raised an eyebrow, but Mraize didn’t give any sign that he knew Shallan. He slouched like the other soldiers, holding a halberd and glaring at Adolin.

Ialai hadn’t set out chairs for them. She sat with her hands in her lap, sleeved safehand beneath her freehand, lit by lamps on pedestals at either side of the room. She looked particularly vengeful by that unnatural flickering light.

“Did you know,” Ialai said, “that after whitespines make a kill, they will eat, then hide near the carcass?”

“It’s one of the dangers in hunting them, Brightness,” Adolin said. “You assume that you’re on the beast’s trail, but it might be lurking nearby.”

“I used to wonder at this behavior until I realized the kill will attract scavengers, and the whitespine is not picky. The ones that come to feast on its leavings become another meal themselves.”

The implication of the conversation seemed clear to Shallan. Why have you returned to the scene of the kill, Kholin?

“We want you to know, Brightness,” Adolin said, “that we take the murder of a highprince very seriously. We are doing everything we can to prevent this from happening again.”

Oh, Adolin…

“Of course you are,” Ialai said. “The other highprinces are now too afraid to stand up to you.”

Yes, he’d walked right into that one. But Shallan didn’t take over; this was Adolin’s task, and he’d invited her for support, not to speak for him. Honestly, she wouldn’t be doing much better. She’d just be making diff rent mistakes.

“Can you tell us of anyone who might have had the opportunity and motive for killing your husband?” Adolin said. “Other than my father, Brightness.”

“So even you admit that—”

“It’s strange,” Adolin snapped. “My mother always said she thought you were clever. She admired you, and wished she had your wit. Yet here, I see no proof of that. Honestly, do you really think that my father would withstand Sadeas’s insults for years—weather his betrayal on the Plains, suffer that dueling fiasco—only to assassinate him now? Once Sadeas was proven wrong about the Voidbringers, and my father’s position is secure? We both know my father wasn’t behind your husband’s death. To claim otherwise is simple idiocy.”

Shallan started. She hadn’t expected that from Adolin’s lips. Strikingly, it seemed to her to be the precise thing he’d needed to say. Cut away the courtly language. Deliver the straight and earnest truth.

Ialai leaned forward, inspecting Adolin and chewing on his words. If there was one thing Adolin could convey, it was authenticity.

“Fetch him a chair,” Ialai said to Mraize.

“Yes, Brightness,” he said, his voice thick with a rural accent that bordered on Herdazian.

Ialai then looked to Shallan. “And you. Make yourself useful. There are teas warming in the side room.”

Shallan sniffed at the treatment. She was no longer some inconsequential ward, to be ordered about. However, Mraize lurched off in the same direction she’d been told to go, so Shallan bore the indignity and stalked after him.

The next room was much smaller, cut out of the same stone as the others, but with a muted pattern of strata. Oranges and reds that blended together so evenly you could almost pretend the wall was all one hue. Ialai’s people had been using it for storage, as evidenced by the chairs in one corner. Shallan ignored the warm jugs of tea heating on fabrials on the counter and stepped close to Mraize.

“What are you doing here?” she hissed at him.

His chicken chirped softly, as if in agitation.

“I’m keeping an eye on that one,” he said, nodding toward the other room. Here, his voice became refined, losing the rural edge. “We have interest in her.”

“So she’s not one of you?” Shallan asked. “She’s not a… Ghostblood?”

“No,” he said, eyes narrowing. “She and her husband were too wild a variable for us to invite. Their motives are their own; I don’t think they align to those of anyone else, human or listener.”

“The fact that they’re crem didn’t enter into it, I suppose.”

“Morality is an axis that doesn’t interest us,” Mraize said calmly. “Only loyalty and power are relevant, for morality is as ephemeral as the changing weather. It depends upon the angle from which you view it. You will see, as you work with us, that I am right.”

“I’m not one of you,” Shallan hissed.

“For one so insistent,” Mraize said, picking up a chair, “you were certainly free in using our symbol last night.”

Shallan froze, then blushed furiously. So he knew about that? “I…”

“Your hunt is worthy,” Mraize said. “And you are allowed to rely upon our authority to achieve your goals. That is a benefit of your membership, so long as you do not abuse it.”

“And my brothers? Where are they? You promised to deliver them to me.”

“Patience, little knife. It has been but a few weeks since we rescued them. You will see my word fulfilled in that matter. Regardless, I have a task for you.”

“A task?” Shallan snapped, causing the chicken to chirp at her again. “Mraize, I’m not going to do some task for you people. You killed Jasnah.”

“An enemy combatant,” Mraize said. “Oh, don’t look at me like that. You know full well what that woman was capable of, and what she got herself into by attacking us. Do you blame your wonderfully moral Blackthorn for what he did in war? The countless people he slaughtered?”

“Don’t deflect your evils by pointing out the faults of others,” Shallan said. “I’m not going to further your cause. I don’t care how much you demand that I Soulcast for you, I’m not going to do it.”

“So quick to insist, yet you acknowledge your debt. One Soulcaster lost, destroyed. But we forgive these things, for missions undertaken. And before you object again, know that the task we require of you is one you’re already undertaking. Surely you have sensed the darkness in this place. The… wrongness.”

Shallan looked about the small room, flickering with shadows from a few candles on the counter.

“Your task,” Mraize said, “is to secure this location. Urithiru must remain strong if we are to properly use the advent of the Voidbringers.”

“Use them?”

“Yes,” Mraize said. “This is a power we will control, but we must not let either side gain dominance yet. Secure Urithiru. Hunt the source of the darkness you feel, and expunge it. This is your task. And for it I will give payment in information.” He leaned closer to her and spoke a single word. “Helaran.”

He lifted the chair and walked out, adopting a more bumbling gait, stumbling and almost dropping the chair. Shallan stood there, stunned. Helaran. Her eldest brother had died in Alethkar—where he’d been for mysterious reasons.

Storms, what did Mraize know? She glared after him, outraged. How dare he tease with that name!

Don’t focus on Helaran right now. Those were dangerous thoughts, and she could not become Veil now. Shallan poured herself and Adolin cups of tea, then grabbed a chair under her arm and awkwardly navigated back out. She sat down beside Adolin, then handed him a cup. She took a sip and smiled at Ialai, who glared at her, then directed Mraize to fetch a cup.

“I think,” Ialai said to Adolin, “that if you honestly wish to solve this crime, you won’t be looking at my husband’s former enemies. Nobody had the opportunity or motives that you would find in your warcamp.”

Adolin sighed. “We established that—”

“I’m not saying Dalinar did this,” Ialai said. She seemed calm, but she gripped the sides of her chair with white-knuckled hands. And her eyes… makeup could not hide the redness. She’d been crying. She was truly upset.

Unless it was an act. I could fake crying, Shallan thought, if I knew that someone was coming to see me, and if I believed the act would strengthen my position.

“Then what are you saying?” Adolin asked.

“History is rife with examples of soldiers assuming orders when there were none,” Ialai said. “I agree that Dalinar would never knife an old friend in dark quarters. His soldiers may not be so inhibited. You want to know who did this, Adolin Kholin? Look among your own ranks. I would wager the princedom that somewhere in the Kholin army is a man who thought to do his highprince a service.”

“And the other murders?” Shallan said.

“I do not know the mind of this person,” Ialai said. “Maybe they have a taste for it now? In any case, I think we can agree this meeting serves no further purpose.” She stood up. “Good day, Adolin Kholin. I hope you will share what you discover with me, so that my own investigator can be better informed.”

“I suppose,” Adolin said, standing. “Who is leading your investigation? I’ll send him reports.”

“His name is Meridas Amaram. I believe you know him.”

Shallan gaped. “Amaram? Highmarshal Amaram?”

“Of course,” Ialai said. “He is among my husband’s most acclaimed generals.”

Amaram. He’d killed her brother. She glanced at Mraize, who kept his expression neutral. Storms, what did he know? She still didn’t understand where Helaran had gotten his Shardblade. What had led him to clash with Amaram in the first place?

“Amaram is here?” Adolin asked. “When?”

“He arrived with the last caravan and scavenging crew that you brought through the Oathgate. He didn’t make himself known to the tower, but to me alone. We have been seeing to his needs, as he was caught out in a storm with his attendants. He assures me he will return to duty soon, and will make finding my husband’s murderer a priority.”

“I see,” Adolin said.

He looked to Shallan, and she nodded, still stunned. Together they collected her soldiers from right inside the door, and left into the hallway beyond.

“Amaram,” Adolin hissed. “Bridgeboy isn’t going to be happy about this. They have a vendetta, those two.”

Not just Kaladin.

“Father originally appointed Amaram to refound the Knights Radiant,” Adolin continued. “If Ialai has taken him in after he was so soundly discredited… The mere act of it calls Father a liar, doesn’t it? Shallan?”

She shook herself and took a deep breath. Helaran was long dead. She would worry about getting answers from Mraize later.

“It depends on how she spins things,” she said softly, walking beside Adolin. “But yes, she implies that Dalinar is at the least overly judgmental in his treatment of Amaram. She’s reinforcing her side as an alternative to your father’s rule.”

Adolin sighed. “I’d have thought that without Sadeas, maybe it would get easier.”

“Politics is involved, Adolin—so by definition it can’t be easy.” She took his arm, wrapping hers around it as they passed another group of hostile guards.

“I’m terrible at this,” Adolin said softly. “I got so annoyed in there, I almost punched her. You watch, Shallan. I’ll ruin this.”

“Will you? Because I think you’re right about there being multiple killers.”

“What? Really?”

She nodded. “I heard some things while I was out last night.”

“When you weren’t staggering around drunk, you mean.”

“I’ll have you know I’m a very graceful drunk, Adolin Kholin. Let’s go…” She trailed off as a pair of scribes ran past in the hallway, heading toward Ialai’s rooms at a shocking speed. Guards marched after them.

Adolin caught one by the arm, nearly provoking a fight as the man cursed at the blue uniform. The fellow, fortunately, recognized Adolin’s face and held himself back, hand moving off the axe in a sling to his side.

“Brightlord,” the man said, reluctant.

“What is this?” Adolin said. He nodded down the hall. “Why is everyone suddenly talking at that guard post farther along?”

“News from the coast,” the guard finally said. “Stormwall spotted in New Natanan. The highstorms. They’ve returned.”

Chapter 23

Storming Strange

I am no poet, to delight you with clever allusions.

—From Oathbringer, preface

I don’t got any meat to sell,” the old lighteyes said as he led Kaladin into the storm bunker. “But your brightlord and his men can weather in here, and for cheap.” He waved his cane toward the large hollow building. It reminded Kaladin of the barracks on the Shattered Plains—long and narrow, with one small end pointed eastward.

“We’ll need it to ourselves,” Kaladin said. “My brightlord values his privacy.”

The elderly man glanced at Kaladin, taking in the blue uniform. Now that the Weeping had passed, it looked better. He wouldn’t wear it to an officer’s review, but he’d spent some good time scrubbing out the stains and polishing the buttons.

Kholin uniform in Vamah lands. It could imply a host of things. Hopefully one of them was not “This Kholin offi er has joined a bunch of runaway parshmen.”

“I can give you the whole bunker,” the merchant said. “Was supposed to be renting it to some caravans out of Revolar, but they didn’t show.”

“What happened?”

“Don’t know,” he said. “But it’s storming strange, I’d say. Three caravans, with different masters and goods, all gone silent. Not even a runner to give me word. Glad I took ten percent up front.”

Revolar. It was Vamah’s seat, the largest city between here and Kholinar.

“We’ll take the bunker,” Kaladin said, handing over some dun spheres. “And whatever food you can spare.”

“Not much, by an army’s scale. Maybe a sack of longroots or two. Some lavis. Was expectin’ one of those caravans to resupply me.” He shook his head, expression distant. “Strange times, Corporal. That wrong-way storm. You reckon it will keep coming back?”

Kaladin nodded. The Everstorm had hit again the day before, its second occurrence—not counting the initial one that had only come in the far east. Kaladin and the parshmen had weathered this one, upon warning from the unseen spren, in an abandoned mine.

“Strange times,” the old man said again. “Well, if you do need meat, there’s been a nest of wild hogs rooting about in the ravine to the south of here. This is Highlord Cadilar’s land though, so um.… Well, you just understand that.” If Kaladin’s fictional “brightlord” was traveling on the king’s orders, they could hunt the lands. If not, killing another highlord’s hogs would be poaching.

The old man spoke like a backwater farmer, light yellow eyes notwithstanding, but he’d obviously made something of himself running a waystop. A lonely life, but the money was probably quite good.

“Let’s see what food I can find you here,” the old man said. “Follow along. Now, you’re sure a storm is coming?”

“I have charts promising it.”

“Well, bless the Almighty and Heralds for that, I suppose. Will catch some people surprised, but it will be nice to be able to work my spanreed again.”

Kaladin followed the man to a stone rootshed on the leeward edge of his home, and haggled—briefly—for three sacks of vegetables. “One other thing,” Kaladin added. “You can’t watch the army arrive.”

“What? Corporal, it’s my duty to see your people settled in—”

“My brightlord is a very private person. It’s important nobody know of our passing. Very important.” He laid his hand on his belt knife.

The lighteyed man just sniffed. “I can be trusted to hold my tongue, soldier. And don’t threaten me. I’m sixth dahn.” He raised his chin, but when he hobbled back into his house, he shut the door tight and pulled closed the stormshutters.

Kaladin transferred the three sacks into the bunker, then hiked out to where he’d left the parshmen. He kept glancing about for Syl, but of course he saw nothing. The Voidspren was following him, hidden, likely to make sure he didn’t do anything underhanded.

They made it back right before the storm.

Khen, Sah, and the others had wanted to wait until dark—unwilling to trust that the old lighteyes wouldn’t spy on them. But the wind had started blowing, and they’d finally believed Kaladin that a storm was imminent.

Kaladin stood by the bunker’s doorway, anxious as the parshmen piled in. They’d picked up other groups in the last few days, led by unseen Voidspren that he was told darted away once their charges were delivered. Their numbers were now verging on a hundred, including the children and elderly. Nobody would tell Kaladin their end goal, only that the spren had a destination in mind.

Khen was last through the door; the large, muscled parshwoman lingered, as if she wanted to watch the storm. Finally she took their spheres— most of which they’d stolen from him—and locked the sack into the iron-banded lantern on the wall outside. She waved Kaladin through the door, then followed, barring it closed.

“You did well, human,” she said to Kaladin. “I’ll speak for you when we reach the gathering.”

“Thanks,” Kaladin said. Outside, the stormwall hit the bunker, making the stones shake and the very ground rattle.

The parshmen settled down to wait. Hesh dug into the sacks and inspected the vegetables with a critical eye. She’d worked the kitchens of a manor.

Kaladin settled with his back to the wall, feeling the storm rage outside. Strange, how he could hate the mild Weeping so much, yet feel a thrill when he heard thunder beyond these stones. That storm had tried its best to kill him on several occasions. He felt a kinship to it—but still a wariness. It was a sergeant who was too brutal in training his recruits.

The storm would renew the gems outside, which included not only spheres, but the larger gemstones he’d been carrying. Once renewed, he— well, the parshmen—would have a wealth of Stormlight.

He needed to make a decision. How long could he delay flying back to the Shattered Plains? Even if he had to stop at a larger city to trade his dun spheres for infused ones, he could probably make it in under a day.

He couldn’t dally forever. What were they doing at Urithiru? What was the word from the rest of the world? The questions hounded him. Once, he had been happy to worry only about his own squad. After that, he’d been willing to look after a battalion. Since when had the state of the entire world become his concern?

I need to steal back my spanreed at the very least, and send a message to Brightness Navani.

Something flickered at the edge of his vision. Syl had come back? He glanced toward her, a question on his lips, and barely stopped the words as he realized his error.

The spren beside him was glowing yellow, not blue-white. The tiny woman stood on a translucent pillar of golden stone that had risen from the ground to put her even with Kaladin’s gaze. It, like the spren herself, was the yellow-white color of the center of a flame.

She wore a flowing dress that covered her legs entirely. Hands behind her back, she inspected him. Her face was shaped oddly—narrow, but with large, childlike eyes. Like someone from Shinovar.

Kaladin jumped, which caused the little spren to smile.

Pretend you don’t know anything about spren like her, Kaladin thought. “Um. Uh… I can see you.”

“Because I want you to,” she said. “You are an odd one.”

“Why… why do you want me to see you?”

“So we can talk.” She started to stroll around him, and at each step, a spike of yellow stone shot up from the ground and met her bare foot. “Why are you still here, human?”

“Your parshmen took me captive.”

“Your mother teach you to lie like that?” she asked, sounding amused. “They’re less than a month old. Congratulations on fooling them.” She stopped and smiled at him. “I’m a tad older than a month.”

“The world is changing,” Kaladin said. “The country is in upheaval. I guess I want to see where this goes.”

She contemplated him. Fortunately, he had a good excuse for the bead of sweat that trickled down the side of his face. Facing a strangely intelligent, glowing yellow spren would unnerve anyone, not just a man with too many things to hide.

“Would you fight for us, deserter?” she asked.

“Would I be allowed?”

“My kind aren’t nearly as inclined toward discrimination as yours. If you can carry a spear and take orders, then I certainly wouldn’t turn you away.” She folded her arms, smiling in a strangely knowing way. “The final decision won’t be mine. I am but a messenger.”

“Where can I find out for certain?”

“At our destination.”

“Which is…”

“Close enough,” the spren said. “Why? You have pressing appointments elsewhere? Off for a beard trim perhaps, or a lunch date with your grandmother?”

Kaladin rubbed at his face. He’d almost been able to forget about the hairs that prickled at the sides of his mouth.

“Tell me,” the spren asked, “how did you know that there would be a highstorm tonight?”

“Felt it,” Kaladin said, “in my bones.”

“Humans cannot feel storms, regardless of the body part in question.”

He shrugged. “Seemed like the right time for one, with the Weeping having stopped and all.”

She didn’t nod or give any visible sign of what she thought of that comment. She merely held her knowing smile, then faded from his view.

Chapter 24

Men of Blood and Sorrow

I have no doubt that you are smarter than I am. I can only relate what happened, what I have done, and then let you draw conclusions.

—From Oathbringer, preface

Dalinar remembered.

Her name had been Evi. She’d been tall and willowy, with pale yellow hair—not true golden, like the hair of the Iriali, but striking in its own right.

She’d been quiet. Shy, both she and her brother, for all that they’d been willing to flee their homeland in an act of courage. They’d brought Shardplate, and…

That was all that had emerged over the last few days. The rest was still a blur. He could recall meeting Evi, courting her—awkwardly, since both knew it was an arrangement of political necessity—and eventually entering into a causal betrothal.

He didn’t remember love, but he did remember attraction.

The memories brought questions, like cremlings emerging from their hollows after the rain. He ignored them, standing straight-backed with a line of guards on the field in front of Urithiru, suffering a bitter wind from the west. This wide plateau held some dumps of wood, as part of this space would probably end up becoming a lumberyard.

Behind him, the end of a rope blew in the wind, smacking a pile of wood again and again. A pair of windspren danced past, in the shapes of little people.

Why am I remembering Evi now? Dalinar wondered. And why have I recovered only my first memories of our time together?

He had always remembered the difficult years following Evi’s death, which had culminated in his being drunk and useless on the night Szeth, the Assassin in White, had killed his brother. He assumed that he’d gone to the Nightwatcher to be rid of the pain at losing her, and the spren had taken his other memories as payment. He didn’t know for certain, but that seemed right.

Bargains with the Nightwatcher were supposed to be permanent. Damning, even. So what was happening to him?

Dalinar glanced at his bracer clocks, strapped to his forearm. Five minutes late. Storms. He’d been wearing the thing barely a few days, and already he was counting minutes like a scribe.

The second of the two watch faces—which would count down to the next highstorm—still hadn’t been engaged. A single highstorm had come, blessedly, carrying Stormlight to renew spheres. It seemed like so long since they’d had enough of that.

However, it would take until the next highstorm for the scribes to make guesses at the current pattern. Even then they could be wrong, as the Weeping had lasted far longer than it should have. Centuries—millennia— of careful records might now be obsolete.

Once, that alone would have been a catastrophe. It threatened to ruin planting seasons and cause famines, to upend travel and shipping, disrupting trade. Unfortunately, in the face of the Everstorm and the Voidbringers, it was barely third on the list of cataclysms.

The cold wind blew at him again. Before them, the grand plateau of Urithiru was ringed by ten large platforms, each raised about ten feet high, with steps up beside a ramp for carts. At the center of each one was a small building containing the device that—

With a bright flash, an expanding wave of Stormlight spread outward from the center of the second platform from the left. When the Light faded, Dalinar led his troop of honor guards up the wide steps to the top. They crossed to the building at the center, where a small group of people had stepped out and were now gawking at Urithiru, surrounded by awespren.

Dalinar smiled. The sight of a tower as wide as a city and as tall as a small mountain… well, there wasn’t anything else like it in the world.

At the head of the newcomers was a man in burnt orange robes. Aged, with a kindly, clean-shaven face, he stood with his head tipped back and jaw lowered as he regarded the city. Near him stood a woman with silvery hair pulled up in a bun. Adrotagia, the head Kharbranthian scribe.

Some thought she was the true power behind the throne; others guessed it was that other scribe, the one they had left running Kharbranth in its king’s absence. Whoever it was, they kept Taravangian as a figurehead— and Dalinar was happy to work through him to get to Jah Keved and Kharbranth. This man had been a friend to Gavilar; that was good enough for Dalinar. And he was more than glad to have at least one other monarch at Urithiru.

Taravangian smiled at Dalinar, then licked his lips. He seemed to have forgotten what he wanted to say, and had to glance at the woman beside him for support. She whispered, and he spoke loudly after the reminder.

“Blackthorn,” Taravangian said. “It is an honor to meet you again. It has been too long.”

“Your Majesty,” Dalinar said. “Thank you so much for responding to my call.” Dalinar had met Taravangian several times, years ago. He remembered a man of quiet, keen intelligence.

That was gone now. Taravangian had always been humble, and had kept to himself, so most didn’t know he’d been intelligent once—before his strange illness five years ago, which Navani was fairly certain covered an apoplexy that had permanently wounded his mental capacities.

Adrotagia touched Taravangian’s arm and nodded toward someone standing with the Kharbranthian guards: a middle-aged lighteyed woman wearing a skirt and blouse, after a Southern style, with the top buttons of the blouse undone. Her hair was short in a boyish cut, and she wore gloves on both hands.

The strange woman stretched her right hand over her head, and a Shardblade appeared in it. She rested it with the flat side against her shoulder.

“Ah yes,” Taravangian said. “Introductions! Blackthorn, this is the newest Knight Radiant. Malata of Jah Keved.”

King Taravangian gawked like a child as they rode the lift toward the top of the tower. He leaned over the side far enough that his large Thaylen bodyguard rested a careful hand on the king’s shoulder, just in case.

“So many levels,” Taravangian said. “And this balcony. Tell me, Brightlord. What makes it move?”

His sincerity was so unexpected. Dalinar had been around Alethi politicians so much that he found honesty an obscure thing, like a language he no longer spoke.

“My engineers are still studying the lifts,” Dalinar said. “It has to do with conjoined fabrials, they believe, with gears to modulate speed.”

Taravangian blinked. “Oh. I meant… is this Stormlight? Or is someone pulling somewhere? We had parshmen do ours, back in Kharbranth.”

“Stormlight,” Dalinar said. “We had to replace the gemstones with infused ones to make it work.”

“Ah.” He shook his head, grinning.

In Alethkar, this man would never have been able to hold a throne after the apoplexy struck him. An unscrupulous family would have removed him by assassination. In other families, someone would have challenged him for his throne. He’d have been forced to fight or abdicate.

Or… well, someone might have muscled him out of power, and acted like king in all but name. Dalinar sighed softly, but kept a firm grip on his guilt.

Taravangian wasn’t Alethi. In Kharbranth—which didn’t wage war—a mild, congenial figurehead made more sense. The city was supposed to be unassuming, unthreatening. It was a twist of luck that Taravangian had also been crowned king of Jah Keved, once one of the most powerful kingdoms on Roshar, following its civil war.

He would normally have had trouble keeping that throne, but perhaps Dalinar might lend him some support—or at least authority—through association. Dalinar certainly intended to do everything he could.

“Your Majesty,” Dalinar said, stepping closer to Taravangian. “How well guarded is Vedenar? I have a great number of troops with too much idle time. I could easily spare a battalion or two to help secure the city. We can’t afford to lose the Oathgate to the enemy.”

Taravangian glanced at Adrotagia.

She answered for him. “The city is secure, Brightlord. You needn’t fear. The parshmen made one push for the city, but there are still many Veden troops available. We fended the enemy off, and they withdrew eastward.”

Toward Alethkar, Dalinar thought.

Taravangian again looked out into the wide central column, lit from the sheer glass window to the east. “Ah, how I wish this day hadn’t come.”

“You sound as if you anticipated it, Your Majesty,” Dalinar said.

Taravangian laughed softly. “Don’t you? Anticipate sorrow, I mean? Sadness… loss…”

“I try not to hasten my expectations in either direction,” Dalinar said. “The soldier’s way. Deal with today’s problems, then sleep and deal with tomorrow’s problems tomorrow.”

Taravangian nodded. “I remember, as a child, listening to an ardent pray to the Almighty on my behalf as glyphwards burned nearby. I remember thinking… surely the sorrows can’t be past us. Surely the evils didn’t actually end. If they had, wouldn’t we be back in the Tranquiline Halls even now?” He looked toward Dalinar, and surprisingly there were tears in his pale grey eyes. “I do not think you and I are destined for such a glorious place. Men of blood and sorrow don’t get an ending like that, Dalinar Kholin.”

Dalinar found himself without a reply. Adrotagia gripped Taravangian on the forearm with a comforting gesture, and the old king turned away, hiding his emotional outburst. What had happened in Vedenar must have troubled him deeply—the death of the previous king, the field of slaughter.

They rode the rest of the way in silence, and Dalinar took the chance to study Taravangian’s Surgebinder. She’d been the one to unlock—then activate—the Veden Oathgate on the other side, which she’d managed after some careful instructions from Navani. Now the woman, Malata, leaned idly against the side of the balcony. She hadn’t spoken much during their tour of the first three levels, and when she looked at Dalinar, she always seemed to have a hint of a smile on her lips.

She carried a wealth of spheres in her skirt pocket; the light shone through the fabric. Perhaps that was why she smiled. He himself felt relieved to have Light at his fingertips again—and not only because it meant the Alethi Soulcasters could get back to work, using their emeralds to transform rock to grain to feed the hungry people of the tower.

Navani met them at the top level, immaculate in an ornate silver and black havah, her hair in a bun and stabbed through with hairspikes meant to resemble Shardblades. She greeted Taravangian warmly, then clasped hands with Adrotagia. After a greeting, Navani stepped back and let Teshav guide Taravangian and his little retinue into what they were calling the Initiation Room.

Navani herself drew Dalinar to the side. “Well?” she whispered.

“He’s as sincere as ever,” Dalinar said softly. “But…”

“Dense?” she asked.

“Dear, I’m dense. This man has become an idiot.”

“You’re not dense, Dalinar,” she said. “You’re rugged. Practical.”

“I’ve no illusions as to the thickness of my skull, gemheart. It’s done right by me on more than one occasion—better a thick head than a broken one. But I don’t know that Taravangian in his current state will be of much use.”

“Bah,” Navani said. “We’ve more than enough clever people around us, Dalinar. Taravangian was always a friend to Alethkar during your brother’s reign, and a little illness shouldn’t change our treatment of him.”

“You’re right, of course.…” He trailed off “There’s an earnestness to him, Navani. And a melancholy I hadn’t remembered. Was that always there?”

“Yes, actually.” She checked her own arm clock, like his own, though with a few more gemstones attached. Some kind of new fabrial she was tinkering with.

“Any news from Captain Kaladin?”

She shook her head. It had been days since his last check-in, but he’d likely run out of infused rubies. Now that the highstorms had returned, they’d expected something.

In the room, Teshav gestured to the various pillars, each representing an order of Knight Radiant. Dalinar and Navani waited in the doorway, separated from the rest.

“What of the Surgebinder?” Navani whispered.

“A Releaser. Dustbringer, though they don’t like the term. She claims her spren told her that.” He rubbed his chin. “I don’t like how she smiles.”

“If she’s truly a Radiant,” Navani said, “can she be anything but trustworthy? Would the spren pick someone who would act against the best interests of the orders?”

Another question he didn’t know the answer to. He’d need to see if he could determine whether her Shardblade was only that, or if it might be another Honorblade in disguise.

The touring group moved down a set of steps toward the meeting chamber, which took up most of the penultimate level and sloped down to the level below. Dalinar and Navani trailed after them.

Navani, he thought. On my arm. It still gave him a heady, surreal feeling. Dreamlike, as if this were one of his visions. He could vividly remember desiring her. Thinking about her, captivated by the way she talked, the things she knew, the look of her hands as she sketched—or, storms, as she did something as simple as raising a spoon to her lips. He remembered staring at her.

He remembered a specific day on a battlefield, when he had almost let his jealousy of his brother lead him too far—and was surprised to feel Evi slipping into that memory. Her presence colored the old, crusty memory of those war days with his brother.

“My memories continue to return,” he said softly as they paused at the door into the conference room. “I can only assume that eventually it will all come back.”

“That shouldn’t be happening.”

“I thought the same. But really, who can say? The Old Magic is said to be inscrutable.”

“No,” Navani said, folding her arms, getting a stern expression on her face—as if angry with a stubborn child. “In each case I’ve looked into, the boon and curse both lasted until death.”

“Each case?” Dalinar said. “How many did you find?”

“About three hundred at this point,” Navani said. “It’s been difficult to get any time from the researchers at the Palanaeum; everyone the world over is demanding research into the Voidbringers. Fortunately, His Majesty’s impending visit here earned me special consideration, and I had some credit. They say it’s best to patronize the place in person—at least Jasnah always said…”

She took a breath, steadying herself before continuing. “In any case, Dalinar, the research is definitive. We haven’t been able to find a single case where the effects of the Old Magic wore off—and it’s not like people haven’t tried over the centuries. Lore about people dealing with their curses, and seeking any cure for them, is practically its own genre. As my researcher said, ‘Old Magic curses aren’t like a hangover, Brightness.’ ”

She looked up at Dalinar, and must have seen the emotion in his face, for she cocked her head. “What?” she asked.

“I’ve never had anyone to share this burden with,” he said softly. “Thank you.”

“I didn’t find anything.”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“Could you at least confirm with the Stormfather again that his bond with you is absolutely, for sure not what’s causing the memories to come back?”

“I’ll see.”

The Stormfather rumbled. Why would she want me to say more? I have spoken, and spren do not change like men. This is not my doing. It is not the bond.

“He says it’s not him,” Dalinar said. “He’s… annoyed at you for asking again.”

She kept her arms crossed. This was something she shared with her daughter, a characteristic frustration with problems she couldn’t solve. As if she were disappointed in the facts for not arranging themselves more helpfully.

“Maybe,” she said, “something was different about the deal you made. If you can recount your visit to me sometime—with as much detail as you can remember—I’ll compare it to other accounts.”

He shook his head. “There wasn’t much. The Valley had a lot of plants. And… I remember… I asked to have my pain taken away, and she took memories too. I think?” He shrugged, then noticed Navani pursing her lips, her stare sharpening. “I’m sorry. I—”

“It’s not you,” Navani said. “It’s the Nightwatcher. Giving you a deal when you were probably too distraught to think straight, then erasing your memory of the details?”

“She’s a spren. I don’t think we can expect her to play by—or even understand—our rules.” He wished he could give her more, but even if he could dredge up something, this wasn’t the time. They should be paying attention to their guests.

Teshav had finished pointing out the strange glass panes on the inner walls that seemed like windows, only clouded. She moved on to the pairs of discs on the floor and ceiling that looked something like the top and bottom of a pillar that had been removed—a feature of a number of rooms they’d explored.

Once that was done, Taravangian and Adrotagia returned to the top of the room, near the windows. The new Radiant, Malata, lounged in a seat near the wall-mounted sigil of the Dustbringers, staring at it.

Dalinar and Navani climbed the steps to stand by Taravangian. “Breathtaking, isn’t it?” Dalinar asked. “An even better view than from the lift.”

“Overwhelming,” Taravangian said. “So much space. We think… we think that we are the most important things on Roshar. Yet so much of Roshar is empty of us.”

Dalinar cocked his head. Yes… perhaps some of the old Taravangian lingered in there somewhere.

“Is this where you’ll have us meet?” Adrotagia asked, nodding toward the room. “When you’ve gathered all the monarchs, will this be our council chamber?”

“No,” Dalinar said. “This seems too much like a lecture hall. I don’t want the monarchs to feel as if they’re being preached to.”

“And… when will they come?” Taravangian asked, hopeful. “I am looking forward to meeting the others. The king of Azir… didn’t you tell me there was a new one, Adrotagia? I know Queen Fen—she’s very nice. Will we be inviting the Shin? So mysterious. Do they even have a king? Don’t they live in tribes or something? Like Marati barbarians?”

Adrotagia tapped his arm fondly, but looked to Dalinar, obviously curious about the other monarchs.

Dalinar cleared his throat, but Navani spoke.

“So far, Your Majesty,” she said, “you are the only one who has heeded our warning call.”

Silence followed.

“Thaylenah?” Adrotagia asked hopefully.

“We’ve exchanged communications on five separate occasions,” Navani said. “In each one, the queen has dodged our requests. Azir has been even more stubborn.”

“Iri dismissed us almost outright,” Dalinar said with a sigh. “Neither Marabethia nor Rira would respond to the initial request. There’s no real government in the Reshi Isles or some of the middle states. Babatharnam’s Most Ancient has been coy, and most of the Makabaki states imply that they’re waiting for Azir to make a decision. The Shin sent only a quick reply to congratulate us, whatever that means.”

“Hateful people,” Taravangian said. “Murdering so many worthy monarchs!”

“Um, yes,” Dalinar said, uncomfortable at the king’s sudden change in attitude. “Our primary focus has been on places with Oathgates, for strategic reasons. Azir, Thaylen City, and Iri seem most essential. However, we’ve made overtures to everyone who will listen, Oathgate or no. New Natanan is being coy so far, and the Herdazians think I’m trying to trick them. The Tukari scribes keep claiming they will bring my words to their god-king.”

Navani cleared her throat. “We actually got a reply from him, just a bit ago. Teshav’s ward was monitoring the spanreeds. It’s not exactly encouraging.”

“I’d like to hear it anyway.”

She nodded, and went to collect it from Teshav. Adrotagia gave him a questioning glance, but he didn’t dismiss the two of them. He wanted them to feel they were part of an alliance, and perhaps they would have insights that would prove helpful.

Navani returned with a single sheet of paper. Dalinar couldn’t read the script on it, but the lines seemed sweeping and grand—imperious.

“ ‘A warning,’” Navani read, “ ‘from Tezim the Great, last and first man, Herald of Heralds and bearer of the Oathpact. His grandness, immortality, and power be praised. Lift up your heads and hear, men of the east, of your God’s proclamation.

“ ‘None are Radiant but him. His fury is ignited by your pitiful claims, and your unlawful capture of his holy city is an act of rebellion, depravity, and wickedness. Open your gates, men of the east, to his righteous soldiers and deliver unto him your spoils.

“ ‘Renounce your foolish claims and swear yourselves to him. The judgment of the final storm has come to destroy all men, and only his path will lead to deliverance. He deigns to send you this single mandate, and will not speak it again. Even this is far above what your carnal natures deserve.’ ”

She lowered the paper.

“Wow,” Adrotagia said. “Well, at least it’s clear.”

Taravangian scratched at his head, brow furrowed, as if he didn’t agree with that statement at all.

“I guess,” Dalinar said, “we can cross the Tukari off our list of possible allies.”

“I’d rather have the Emuli anyway,” Navani said. “Their soldiers might be less capable, but they’re also… well, not crazy.”

“So… we are alone?” Taravangian said, looking from Dalinar to Adrotagia, uncertain.

“We are alone, Your Majesty,” Dalinar said. “The end of the world has come, and still nobody will listen.”

Taravangian nodded to himself. “Where do we attack first? Herdaz? My aides say it is the traditional first step for an Alethi aggression, but they also point out that if you could somehow take Thaylenah, you’d completely control the Straits and even the Depths.”

Dalinar listened to the words with dismay. It was the obvious assumption. So clear that even simpleminded Taravangian saw it. What else to make of Alethkar proposing a union? Alethkar, the great conquerors? Led by the Blackthorn, the man who had united his own kingdom by the sword?

It was the suspicion that had tainted every conversation with the other monarchs. Storms, he thought. Taravangian didn’t come because he believed in my grand alliance. He assumed that if he didn’t, I wouldn’t send my armies to Herdaz or Thaylenah—I’d send them to Jah Keved. To him.

“We’re not going to attack anyone,” Dalinar said. “Our focus is on the Voidbringers, the true enemy. We will win the other kingdoms with diplomacy.”

Taravangian frowned. “But—”

Adrotagia, however, touched him on the arm and quieted him. “Of course, Brightlord,” she said to Dalinar. “We understand.”

She thought he was lying.

And are you?

What would he do if nobody listened? How would he save Roshar without the Oathgates? Without resources?

If our plan to reclaim Kholinar works, he thought, wouldn’t it make sense to take the other gates the same way? Nobody would be able to fight both us and the Voidbringers. We could seize their capitals and force them—for their own good— to join our unified war effort.

He’d been willing to conquer Alethkar for its own good. He’d been willing to seize the kingship in all but name, again for the good of his people.

How far would he go for the good of all Roshar? How far would he go to prepare them for the coming of that enemy? A champion with nine shadows.

I will unite instead of divide.

He found himself standing at that window beside Taravangian, staring out over the mountains, his memories of Evi carrying with them a fresh and dangerous perspective.

Oathbringer: The Stormlight Archive Book 3 copyright © 2017 Dragonsteel Entertainment, LLC