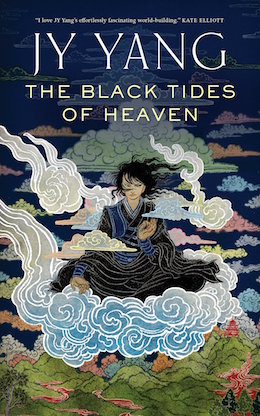

The Black Tides of Heaven is the first of a pair of simultaneous-release novellas by JY Yang, marking the start of their Tensorate series. Mokoya and Akeha are twins, the youngest children of the ruthless Protector of the Kingdom. Their mother is engaged in a complex power struggle with the Grand Monastery and as a result both children are raised there as charges—until Mokoya begins receiving prophetic visions and the children are recalled to the palaces. Akeha, however, is the “spare” child of the pair according to their mother.

The novella is constructed from a series of vignettes that take place over the course of thirty-five years. The Black Tides of Heaven shifts sole focus to Akeha at the middle point when the twins’ lives do, ultimately, separate; the paired novella, The Red Threads of Fortune, will pick up with Mokoya after the events of this book.

Politics are both the center of this novella and the ongoing but unremarkable background, simultaneously. The construction—vignettes spread from “year one” to “year thirty-five”—doesn’t allow for in depth examination of the cultural or political milieu. The reader is immersed as the characters are without explanation or exposition. This creates a paradoxical and pleasurable sense of unshakeable grounding in the setting while avoiding the typical structure of a second-world fantasy novel that would give the reader extensive experience within it.

In effect, Yang treats the world of their novella as real and already-known to the reader. In doing so they trust us to fill in the blanks via observation, logic, and a puzzle-game of implications. There’s a certain craft skill required to make that work, and it’s undeniably present here. I never had a moment of confusion or disorientation because there is a perfect mix of detail and narrative movement to keep the reader comfortable without spoon-feeding them context.

The non-traditional narrative structure works using the same techniques. As we jump from year to year, alighting in different periods of Akeha’s life, we come to understand various things about the Protectorate. Some of these are cultural facts, such as gender being explicitly chosen and confirmed with surgery for most citizens, though some may occupy middle space or approach their physical bodies differently than others. Other facts are political: the Monastery and the government are both juggernauts often at odds; advanced magic and technological progress too are in conflict; the twins’ mother is a despotic but also successful ruler.

There is a plot that accretes through the various chunks of narrative the novella contains. We follow Akeha through his life as events shape him to be a sympathetic revolutionary against his mother, though in the end he does not overthrow her. It’s a personal arc rather than a political arc, but as in reality, the personal and political are deeply intertwined. Without the complex and often violent politics of his nation, Akeha wouldn’t be driven to conflict with his mother—even though he attempted to extricate himself and avoid any involvement. His one rule, when he meets Yongcheow, is that he doesn’t do work that involves the Tensorate; for Yongcheow, though, he changes those rules.

The narrative arc is compelling precisely for the obvious track it avoids. In another book, this might be a tale of revolution against one’s cruel parent/ruler. In The Black Tides of Heaven, the reader instead peers into brief snatches of time: a relationship breaking here, a relationship growing there, a conflict, a failure, a desire to avoid further conflict. The effect is fast-paced and immersive, organic. Yang sprinkles tidbits of worldbuilding and interpersonal conflict throughout that snag the reader’s attention.

For example: it seems the Machinists have managed to create, using a combination of magic and technology, something like a nuclear weapon. That isn’t expounded upon further, past Akeha’s realization that there’s something poisonous and terrible about the after effects of the weapon he tests, but the reader understands the implications. The balance of external story on the page and internal work left for the reader makes for an experience I won’t soon forget, though it’s difficult to describe in terms of “what really happens.”

The treatment of gender and sexuality, too, deserves a nod. The casual use of neutral pronouns for all unconfirmed characters—after all, their genders haven’t been chosen—is well done. So, too, is the acknowledgement that even in a society with gender as a choice, sometimes there are complications. Yongcheow lives as a man, but physically is implied to have not undergone surgery to match, as he must still bind his chest. The twins each confirm different genders: Mokoya chooses to be a woman while Akeha chooses to be a man. It’s also worth noting that Akeha chooses maleness not because it’s right but because it’s closer to right, an interesting detail that Yongcheow’s choice to not be confirmed also sheds some light on.

Also, both Akeha and Mokoya are attracted to men—sometimes, the same man. None of these details require explanation or exposition, though. Yang gives them to us and lets us work through it ourselves, which also creates a sense of natural ease with the characters’ views of gender and attraction. Much like the political setting, the cultural setting is presented as organic and obvious, which creates an even, balanced tone throughout.

The Tensorate series is off to a strong start with The Black Tides of Heaven. The narrative structure and the prose are both top-notch and fresh, the characters are uniquely individual, and the conflicts have a strong grounding in a complex world that we’re just beginning to see the shape of. JY Yang has impressed me, here, and I’m looking forward to more—which we’ll receive immediately, as the twin novella The Red Threads of Fourtune has been released at the same time.

The Black Tides of Heaven and The Red Threads of Fortune are available from Tor.com Publishing.

Read excerpts from Black Tides and Red Threads here.

Check out a review of The Red Threads of Fortune here.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. They have two books out, Beyond Binary: Genderqueer and Sexually Fluid Speculative Fiction and We Wuz Pushed: On Joanna Russ and Radical Truth-telling, and in the past have edited for publications like Strange Horizons Magazine. Other work has been featured in magazines such as Stone Telling, Clarkesworld, Apex, and Ideomancer.