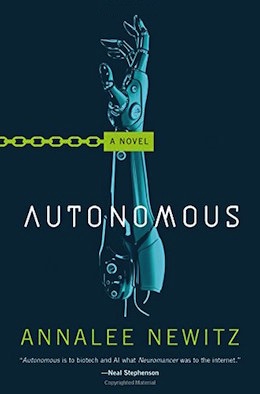

Autonomous is a stand-alone novel set in a near-future world rearranged into economic zones, controlled at large by property law and a dystopic evolution of late-stage capitalism. The points of view alternate between two sides of a skirmish over a patent drug that has catastrophic side-effects: one of our protagonists is a pirate who funds humanitarian drug releases with “fun” drug sales and another is an indentured bot who works for the IPC to crush piracy. As their missions collide, other people are caught up in the blast radius.

While many sf readers are familiar with Newitz, either in her capacity as editor of io9 or as a writer of compelling nonfiction and short stories, this is her first foray into the world of novels and it’s a powerful debut. Wrapped up in a quick, action-oriented plot are a set of sometimes-unresolved and provocative arguments about property law, autonomy, and ownership. Issues of gender and sexuality are also a through-line, considering one of our main characters is a bot whose approach to gender is by necessity quite different than that of their human counterparts.

Jack, a successful humanitarian drug pirate, makes for an engaging perspective on the whole mess of the world in Autonomous. She’s old enough, and has experienced enough, to be world-worn without giving up her version of idealism. At baseline, she’s attempting to do the right thing and discovering herself still in the process—first as a public intellectual revolutionary, then as a disgraced scientist, then as a smuggler and pirate. Conversely, we have Paladin, a bot who has just barely come online and who is indentured to the IPC for at minimum ten years of military service to earn out the contract generated by their creation. When Jack’s pirated productivity drug begins causing rashes of addiction and death, IPC notices—as does the rest of the underground.

So, while Jack is trying to create a solution to the problem and pin the unethical drug on its corporate creators, the IPC sends Eliasz and Paladin to hunt her down. Eliasz, a soldier of sorts for patent enforcement, first perceives Paladin to be male, though Paladin does not have a gender; this causes him distress, as he’s attracted to the bot but resistant to his own repressed sexuality. When he finds out that Paladin’s human network, a brain donated from a dead soldier, is female he asks if it’s all right to call her “she.” After she agrees, they embark on a romantic and sexual relationship that is complicated by the fact that Paladin has loyalty and attachment programs running in the background at all times.

Paladin, in a sense, cannot consent—and the novel explores this in a complex way, while also dealing with her agreement to go by a pronoun and gender she does not feel to maintain a relationship with a human she is engaged by. There’s a ringing discomfort to this that is, strangely, familiar: for several nonbinary readers, I suspect it will strike a familiar chord of conceding one’s own comfort for the comfort of a partner in terms of pronouns or perception, even if they don’t quite fit one’s own self. Paladin does not have a gender; nonetheless, Paladin goes by both he and she throughout the novel, and refers to herself using female pronouns once Eliasz begins to.

And Eliasz, himself a victim of an upbringing in the indenture system and concurrent repressive punishment for sexuality, is desperate to believe that he is in love with a woman. However conflicted and problematic he is, he also is willing to ask consent as much as he can and to then buy and release Paladin’s contract so she can be free to make her own choices about their relationship. At this point, too, Paladin’s brain has been damaged, leaving her unable to recognize human facial expressions—so, she has also become a disabled veteran, in the context of their world.

These background relationships, as well as the relationships between Jack, Threezed, and Med, among others, are all fascinating and frequently queer. Gender seems mostly irrelevant to the majority of the humans in the novel. Eliasz is the only one who struggles with his attraction. The rest have much more to do with power, consent, and privilege, which also renders them consistently engaging.

Spoilers follow.

Perhaps the most compelling and unexpected thing for me about Autonomous is that it does not offer large-scale resolution to a single one of the social conflicts our protagonists come up against. The indenture system for humans and bots remains brutal and underexamined, oligarchy rules unabated, and even the corporation that willfully created Zacuity gets off without much of a scratch. The conflicts that cost lives and pull apart whole communities are, ultimately, limited to those individuals and communities—and it’s clear that something indescribably bigger will be necessary to change the world in a meaningful way, if it’s possible at all.

The result is a Pyrrhic victory. Medea Cohen, the autonomous bot, is able to publish the cure for Zacuity-addiction to undo the damage done by Jack’s uncontrolled release—and perhaps to make people think twice about using it. However, the corporation is undamaged and able to force the removal of the paper accusing them of producing an addictive drug on purpose. Jack survives and is able to pick her projects up again; Threezed enrolls in college and gets his first non-indentured job; Eliasz and Paladin quit the IPC and travel to Mars, where their human-bot relationship will not be as much of a liability.

Krish dies, though—and so do hundreds of other people, all told, several at the hands of the IPC agents Eliasz and Paladin. Newitz’s argument, ultimately, rests in Autonomous‘s savage and realistic representation of a global capitalism that has, through a series of social maneuvers, consolidated all things as tradeable property, including humans and bots. No one is able to escape participation. The system of indenture is a logical evolution of the current system of wage-labor, taken to its extreme; so, to, are the controlled drug patents that lead to extreme acts of piracy and counter-enforcement.

Therein lies the real horror of Autonomous: it doesn’t feel particularly dystopic, because it’s too close to home. The introduction of artificial intelligences and the resultant commoditization of autonomy across humans and bots, as well as the luxury of functional medical access and wild wealth stratification, are all natural if intensified versions of experiences familiar in contemporary life. Newitz, in looking through this lens and making it relatable and familiar, has done the real work of sf: she has given us a “what if” that forces an examination of our current moment, our current priorities, and our current dangers.

It’s got big ideas, this book, and it refuses to offer the wish-fulfillment of simple large-scale solutions. Autonomous doesn’t shy from the towering realities of power, privilege, and social dysfunction. The reader must swallow both the individual success of the surviving protagonists and the failure of global change—and that’s fascinating as a thematic stance that forces the reader to occupy a more “average” role as opposed to the role of a savior-figure. It isn’t necessarily nihilistic, but it is rather grim. I appreciated that careful balance.

As a whole, Autonomous is a fantastic debut. The plot is fast and sharp; the characters are complex and flawed and often horrible; the conflicts are full of ethical grey areas and self-justification. The blurbs from Neal Stephenson and William Gibson feel especially prescient, as this is certainly a book that knows its predecessors in cyberpunk and branches off from them with intention and skill. The true stand-out difference is in Newitz’s refusal to offer a clean, simple fix to a set of messy global conflicts, instead giving us individuals, their choices, and a crushing sense of the vastness of the problems late-capitalism nurtures. Narrative closure is achieved, as is personal closure—but political closure remains out of reach, a fight still in progress with an uncertain conclusion.

Autonomous is available now from Tor Books.

Read an excerpt from the novel here.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. They have two books out, Beyond Binary: Genderqueer and Sexually Fluid Speculative Fiction and We Wuz Pushed: On Joanna Russ and Radical Truth-telling, and in the past have edited for publications like Strange Horizons Magazine. Other work has been featured in magazines such as Stone Telling, Clarkesworld, Apex, and Ideomancer.