I think it’s fair to assert that the trope of the damsel in distress has been falling away in contemporary fantasy for some time, but I’d like to shine a light on one who helped break that literary mold even in the 1970s: Lúthien Tinúviel. This famous Elfmaiden, who stars in the iconic love story of J.R.R. Tolkien’s legendarium, didn’t need to be rescued like a video game princess. She broke out of bondage, rescued her own questing boyfriend, and personally took on the big boss at the end of all levels. It’s like… imagine if in the original game, you play as Zelda, and you get to bust her out of Ganon’s prison, find all the Triforce pieces with Link, then fight your way through Death Mountain together.

Let’s be clear. There are innumerable wonderful heroines in the genre, and the list grows every day. I am merely positing that Lúthien, conceptually, is one of the best. This badass heroine rises up from the fairy tale beauty and Eldar privilege of her birthright to get her hands dirty and solve problems like a big girl. She and her mortal betrothed, Beren, are equals even when others around them—immortal and ostensibly wise beings—choose not to see it. They are a two-person army of determination and doom. (To be fair, they do have the help of a magical dog/fifth wheel in their adventures—more on him later.) They are true to one another in the face of every opposition: Lúthien’s own dad, various grudge-bearing Elves, a legion of vile monsters, and a constant barrage of dire prophecies.

You surely know of Éowyn, a real stand-out gal in a big book featuring a hell of a lot of fellas. She’s a woman who does what, truly, no man can: kick the Witch-King’s ass—not just because of a loophole in prophecy but because she has the guts to challenge him. And of course you know of Galadriel, who is both wise and powerful, but in the final days of the Third Age she is more soothsaying and advisory than enemy slaying. And you probably know of Arwen, who is more of a behind-the-scenes mover and the chief source of moral support for Aragorn. We can scoff at Arwen’s assumed demureness—and Tolkien’s decision to keep her largely out of sight—but Strider wouldn’t have become King Elessar without her. Yet these three ladies are why Lúthien is—to me—of vital importance in the bigger picture, as she is the forerunner of all women who get shit done in Middle-earth. These three, and many more, are the echoes of her badassery.

Would some of us rather J.R.R. have added plenty more female characters of varying complexity and power to his stories? Of course we would. The truth is, there are more influential women than you’d think to be found in the pages of 1977’s The Silmarillion. It’s just that Lúthien serves up something special, with a side order of blood, poison, and enchantment.

If you haven’t actually checked out Chapter 19 of The Silmarillion, “Of Beren and Lúthien,” I hope to convince you to do so. Reading the preceding chapters would provide helpful context on the state of Middle-earth at the time (in the First Age), but it’s still something of a standalone tale. I find myself rereading it more than any other just for a fix. The adventure and wonderment of The Lord of the Rings is phenomenal, but it’s understated and drawn-out compared to how much punch Tolkien packs into this one particular story. Elves, Men, and romance aside, it’s also chock full of mighty spells, magic weapons, werewolves, vampires, magic dogs, sing-offs, dying words, and the infamous Morgoth himself (aka Sauron’s original master).

One thing to appreciate about this tale is the fact that both its hero and its heroine share equal billing. Neither is the main character and neither upstages the other; they tag-team their way to Morgoth’s own throne room in the depths of what amounts to Hell in this world. To be fair, it does take some time to get to the point of gender symmetry, but that’s part of the journey. Despite the folkloric narrative style of The Silmarillion, there is some measure of chauvinism to be found among its characters. Even the Elves, the first Children of Ilúvatar (God in all but name), do not name women often among their heroes. Yet there are, at least, as many Ladies of the Valar (archangels) as there are Lords, and in Middle-earth’s power couples, it’s usually the female who is the greater: witness Galadriel to Celeborn or, in this story, Melian to Thingol.

Although Beren loves Lúthien above all things and is an honorable Man, even he overlooks her potential at first and tries to shelter her from harm… until she refuses to back down. Three times it takes to cut through his pride and intense desire to protect her. Then he relents as any man should when he sees he is not always the wiser nor the stronger.

But let’s back up. Just who is this lady and why is her story so worth knowing? Tolkien, who popularized many of the fantasy elements we now call tropes today, turned the fairy tale princess conceit on its head with Lúthien, even as he showcased his love and reinvention of pre-existing folktales and mythologies. I want her, and him, to get more credit for this.

Most readers first encounter the tale of Beren and Lúthien in its shortest form as told by Aragorn in Chapter 11 of The Fellowship of the Ring, “A Knife in the Dark” when he and the hobbits are gathered around a fire at Weathertop. They’d been asking him about elder times since he seemed to know a lot about the past. Samwise specifically expressed an interest in hearing more about Elves—who, it’s worth noting, are in their time of fading from Middle-earth during the War of the Ring.

‘I will tell you the tale of Tinúviel,’ said Strider, ‘in brief—for it is a long tale of which the end is not known; and there are none now, except Elrond, that remember it aright as it was told of old. It is a fair tale, though it is sad, as are all the tales of Middle-earth, and yet it may lift up your hearts.’

And Aragorn does mean “in brief,” as we get from him only the nutshell version of Lúthien’s tale, first a bit in song then in prose in one big paragraph. In real world chronology, Tolkien wrote the tale in epic form in the 1920s as a poem (which can be found in its unfinished form in The Lays of Beleriand) and he did so before even working on The Lord of the Rings. Still, Aragorn’s fireside yarn is enough for the hobbits, and more importantly, it sets the stage for his and Arwen’s own parallel, behind-the-scenes-until-the-end story. But truly, the tale of Aragorn and Arwen—while long-suffering and exceedingly hard-won—isn’t quite as fast and fierce as that of their First Age forebears. Which is to say Aragorn’s story actually has far fewer monsters, spells, hunts, dungeons, and magic dogs in it.

Oh, did I not mention the supernatural canines? This tale has a bunch!

Lúthien’s story is also fairly unique in that the heroes are not merely reactive to the villains. In a lot of classics, from “Beowulf” to The Odyssey to Star Wars to The Lord of the Rings itself, the good guys are spurred into motion because if they don’t, bad things will happen. Grendel and his mom come busting in, forcing Beowulf to retaliate. Odysseus is just trying to get home while meddling gods make his life complicated. Stormtroopers shoot up Luke’s moisture farm so a wise old hermit comes out of hiding and prompts him to unwittingly oppose his dad who was helping his boss blow up planets (that about the short of it?). And in Rings, Sauron begins to rise again while searching for his lost jewelry with new intel, threatening everyone, and this forces Gandalf to stir up heroes to oppose him.

But in Lúthien’s story, the great enemy Morgoth is just sitting there on his dark throne thinking his dark thoughts—for all intents and purposes, and as much as he possibly he can—minding his own business. And it’s the good guys who show up and in get all up in his face. Sure, Morgoth’s the author of all evil on Middle-earth and as a rule he constantly antagonizes the Elves of the First Age just to spite Ilúvatar. During the time of Beren’s quest, he wasn’t doing anything personally to either of them beyond his usual policy of having his minions kill their kinsmen whenever possible. But to be fair, he’s always doing that. Par for the course.

The story goes a little something like this and believe me when I say this is very abridged.

So this Man named Beren, who is already high on Morgoth’s shit list for various vengeance-fueled exploits, has been battling his way through lands thick with monsters. Things get so perilous for him that he is forced to flee into the Mountains of Terror, which are called Ered Gorgoroth. Seriously, how bad do things have to be when you have to retreat to a place after which a Norwegian black metal band names itself? Pretty bad. But although “[s]heer were the precipices” of these mountains, and “horror and madness” walked in the wilderness before him, Beren manages to come stumbling down, weary and dazed, into a beautiful forestland. And there, one night in his fevered state, he sees Lúthien dancing in a moonlit glade. He falls hard for her, and soon after, she for him. He names her Tinúviel, which means Nightingale or Daughter of Twilight.

See, from his wanderings he had strayed unknowingly into Doriath, the Hidden Kingdom, one of the many secret Elf-lands in the The Silmarillion. Despite the wrathful protest of Lúthien’s father, Thingol, who was king of this realm, the couple are determined to make their biracial, unprecedented relationship work: she is an immortal Elf and he is a mortal Man and the two races cannot share the same ultimate fate. What this means—and it’s a very big deal in Tolkien’s work—is that the afterlives of Elves and Men are not the same. Elves, when they perish, are reincarnated in Valinor, a physical realm in the world far to the west, and sometimes they can even return to Middle-earth. But Men, when they perish, go elsewhere beyond the world altogether, for they are more like guests in Middle-earth and not bound to it as are the Elves. Elves live and relive, while mortals die.

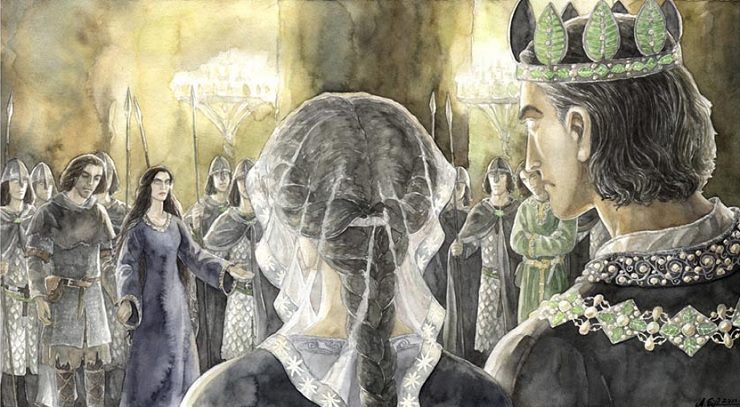

King Thingol knows this and doesn’t want to see his daughter slumming it with some ill-fated, short-lived Man. He speaks harshly and demands to know just who Beren thinks he is daring to woo his daughter. But when Beren is at first daunted, it’s Lúthien who speaks up. Tolkien’s women are not silent for long.

‘He is Beren son of Barahir, lord of Men, mighty foe of Morgoth, the tale of whose deeds is become a song even among the Elves.’

She’s not a fangirl, just a young woman in love and proud of her choice to be with him. And this gives Beren himself courage enough to speak up and defend his own lineage. But it’s still not enough for Thingol, because it never is for Elven lords, is it? He gives Beren an impossible task, one that he figures will totally get rid of the guy. And that’s because it’s a deed that countless Elves and whole armies failed to do many times in the past: reclaim the Silmarils from Morgoth, or even just one.

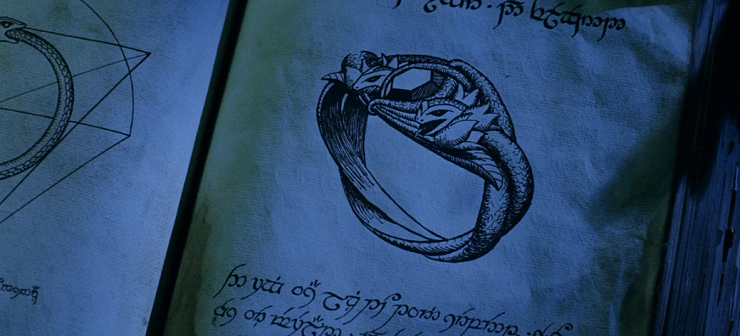

And just what are the Silmarils? They’re the three highly-coveted über gems that fuel many of the conflicts of The Silmarillion. Think epic MacGuffins. They were crafted by the legendary Fëanor, a prince of Elves who was basically the most skilled artisan of all time. Unbreakable, unspeakably lovely gems, they were made to preserve the last vestiges of the light of the Trees of Valinor. These trees of legend don’t otherwise factor into this story but suffice it to say that they were two colossal pillars of light and glory, likened to the sun and the moon, that shone upon the world in ancient times. The trees’ destruction and the subsequent darkening of Middle-earth were contrived by Morgoth, who—not so coincidentally—was also the one who later stole the gems and has held them ever since. Yes, most of Tolkien’s stories are about people fighting over jewelry.

Now, the light of the Silmarils, the last remnants of the light of the Trees of Valinor, could burn even Morgoth’s evil flesh. He’d affixed the gems into a crown and wore it on his head in agony just to snub his hated foes. Which you have to agree was very metal of him.

Back to Beren. If he wanted to get hitched to Lúthien, he would have to retrieve one of these gems straight from Morgoth’s headgear. King Thingol feels clever and smug for demanding the impossible, but Thingol’s wife is not so amused. For one, the mother of Lúthien isn’t actually an Elf at all—which, now that I think about it, makes me think maybe Thingol should have shut up about interracial marriages—nor was she of the race of Men. Nope, Melian was a Maia, a spiritual being on par with the balrogs, the Istari wizards, and Sauron himself. In fact, it was her powers of protection that secured her husband’s kingdom with—and I’m paraphrasing here—an Invisible Fence of Keeping Out Pretty Much All Evil +5. She was the reason everyone was safe and privileged enough to even be talking about such lofty marriage vows.

Since this article is about Lúthien—no, really, it is—let me just pause again and point out that her mom isn’t just some angelic trophy wife. Where Thingol is all pride and wrath (and I assume furious Hugo Weaving eyebrows), Melian brings clear-headed counsel to his kingdom and a wisdom that makes even her high-blooded husband seem childish. And so she knows a thing or two about prophecies. She calls it like she sees it:

‘O King, you have devised cunning counsel. But if my eyes have not lost their sight, it is ill for you, whether Beren fail in his errand, or achieve it. For you have doomed either your daughter, or yourself. And now is Doriath drawn within the fate of a mightier realm.’

Calling for a quest to swipe a Silmaril is no joke. It brings the Oath of Fëanor to the table, and that’s usually bad news. The Oath in question was one Fëanor and his seven sons made back when Morgoth stole the Silmarils, and it essentially invokes death and destruction upon any who dared to keep the Silmarils from his kin. That meant even if Beren succeeded in his quest, holding a Silmaril—nay, even just seeking one—will incur the wrath of Fëanor & Sons. The Oath is a curse, and Thingol is drawing everyone involved into it simply by naming the Silmarils as the price for Lúthien’s hand. Not a smart move, but one made in passion.

Beren, being brave, mighty, and foolish—and above all, in love—just laughs off the king’s ultimatum and says:

‘For little price do Elven-kings sell their daughters: for gems, and things made by craft. But if this be your will, Thingol, I will perform it. And when we meet again my hand shall hold a Silmaril from the Iron Crown; for you have not looked the last upon Beren son of Barahir.’

And off he goes, alone on his impossible quest. And in a normal fairy tale, this is as you would expect. Boy meets girl. Girl’s father dislikes boy and gives boy a suicide mission. Girl stays behind. Because that’s what princesses do—right? Stay with me.

Beren thus leaves and strolls into another nearby hidden Elf-kingdom (Middle-earth is lousy with them), and while he almost becomes target practice for its border guards (kidding, Elves would never miss), they recognize the ring he wears. Why, it’s the Ring of Barahir, the one that Aragorn will wear someday! See, it was once given as a token of friendship to Barahir, Beren’s dad, by an Elf king named Finrod Felagund. And that’s to whom these border guards now escort Beren.

Finrod Felagund is basically the most likeable Elf ever. He’s Galadriel’s brother, for one! He’s the sort of leader who gets his Elf-boots dirty and goes adventuring. Oh, and—fun fact—he’s also the Elf who made first contact with the race of Men when they first arrived on the scene in Middle-earth; he’d spoken well of them to his kin so that these hairy, short-lived Men were not immediately driven away from Elven lands. He also knew Beren’s dad, Barahir, personally—indeed, he’s friends with the whole bloodline—and now, hearing of Beren’s quest, Finrod actually sets aside his crown to join his young friend on his foolish quest.

Seriously, Finrod’s the nicest guy ever. If this was modern Earth, I bet he’d even give up a weekend to help his buddy move, and probably offer to use his own van, too. Just saying he’s that kind of guy.

Finrod brings along his most loyal warriors and together they all set out to take on Morgoth together. But after some crazy adventures—including Finrod disguising them all as Orcs to get through enemy lands—they meet the first boss monster: Morgoth’s right-hand man, the dreaded Maia and future ring-maker, Sauron! Beren’s party is unmasked, defeated, and after a deadly sing-off between Finrod and Sauron (think Epic Rap Battle of History: Silmarillion Edition), evil is the victor and so they’re thrown into the dungeons of the island fortress of Tol-in-Gaurhoth. AKA, the Island of Werewolves. Werewolves, which are totally a thing in Tolkien’s world, even eat some of Finrod’s Elves just to terrify the rest.

Now back to Lúthien! She’s had enough waiting around. She feels in her heart that something is wrong, and when she consults with her literally angelic mother, discovers that Beren is now languishing in Sauron’s dungeons in Tol-in-Gaurhoth. But before she can set out to rescue him, her father learns that his daughter is planning on chasing after her scumbag boyfriend. And he gets stupid about it. Thingol, for all his faults, does love his daughter and rightly fears she would place herself in great peril going after Beren. But his solution is a little sketchy for a mighty Elf king.

He has Lúthien confined in a special house high in the lofty branches of a massive beech tree. It’s opulent and befitting a princess of her stature, but yup, Thingol essentially locks his daughter up in a tower on house arrest. This is, frankly, lousy fathering, and I do wonder at this point why Melian puts up with this—but then, aside from her protective border fencing, the queen seems content to remain advisory. Or perhaps, being prescient, she knows that her daughter solves her own problems…

Enter now the Lúthien Who Gets Things Done. Thingol grounding her is the final straw, and she’s no daddy’s girl. Lúthien enacts her own talents by putting “forth her arts of enchantment,” causing her hair to grow to an exceptional, Rapunzelish length. Here Tolkien’s homage to fairy tales is evident but also twisty, as Lúthien weaves from her dark hair a shadowy, sleep-inducing cloak and a super-long rope, down which she climbs from the great tree herself (no dude climbs to her) and leaves her guards asleep.

On the way to rescue Beren, she crosses paths with the Elf brothers Celegorm and Curufin, who’d been hanging out in Finrod’s nearby kingdom. Now they are are out hunting Sauron’s wolves with Celegorm’s super amazing awesome wolfhound, Huan. These Elves are two of the sons of Fëanor—who you may remember from such oaths as the aforementioned Oath of Fëanor. They’re also arguably the douchiest Elves in The Silmarillion, but Lúthien doesn’t know this yet. Seeing how good-looking she is, and how trusting, Celegorm suddenly desires her for himself. After the two lead her in feigned friendship back to their adopted kingdom—Finrod himself still a prisoner of Sauron’s at this time—they hold her captive. Celegorm even has plans to force her into marrying him so he can up his status among all Elves. But Huan, the horse-sized magical hound of Valinor, who had been given to Celegorm by the Valar long before—and presumably before Celegorm grew into such an asshole—intervenes on Lúthien’s behalf.

Now understand this: Huan is the best dog ever. Despite being normally loyal to his master, he is no dumb beast. Huan is true of heart and highly intelligent. Have you ever heard of Plato, Aristotle, Socrates? Lassie? Morons… compared to the awesomeness of Huan. Coming to love Lúthien himself, in that warm, fuzzy, and pure way only a dog can, he springs her from her prison in the dark of night and they flee the kingdom together. He even allows her to ride on his back, which he isn’t normally cool with anybody doing. But Lúthien is special and Huan is a Very Good Boy.

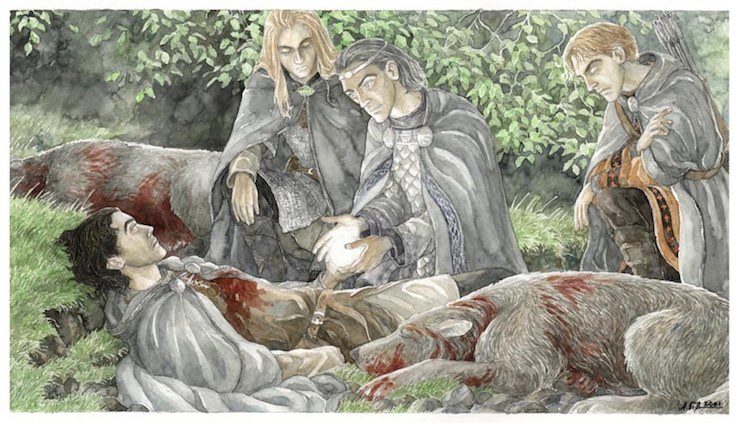

Together they reach Sauron’s island fortress, but sadly, not in time to save Finrod. The Elf king breaks out of his shackles in time to stop one of Sauron’s werewolves from devouring Beren, and with his bare hands Finrod wrestles and slays the beast at the cost of his own life. Death from violence is especially tragic for Elves, but at the same time, isn’t the same as the death of mortals. Finrod would be reincarnated elsewhere, but would not rejoin the world in the same way, and certainly shall never see Beren again. Beren falls into despair, unaware that the Best Girlfriend Ever was already at the bridge of the tower up above.

Now Sauron, who somehow is still more likeable than those damned Elf brothers, is actually pleased to see Lúthien at his doorstep. If he could capture the lovely and much-ballyhooed Elf princess he would win some serious points with his boss, so he sends monster wolf after monster wolf down to subdue her, but Huan dispatches each one easily. So Sauron gets out the big guns in the form of Draugluin, the daddy of all werewolves, the first and meanest of his kind.

The two canines fight savagely until Draugluin, mortally wounded, turns tail then drops dead at Sauron’s feet back inside the tower, after telling his master that it was Huan who had come. Now Sauron has heard of Huan, the great hound of Valinor, as did many, and he knows of the prophecy that Huan would only meet his end by “the mightiest wolf that would ever walk the world.” Since Draugluin was clearly not the one, Sauron decides to make himself into the murderous wolf in question. He changes forms—as Maiar can do from time to time—and goes down from his tower to personally take on the big wolfhound. For he is now Wolf-Sauron, using precisely the sort of sorcery he is denied in The Lord of the Rings: the disembodied “Great Eye” we all know and love would be the best he could manage in those latter days.

Another dog vs. dog battle ensues, but Lúthien is no mere bystander. This lady has agency and guts. She uses the sleep-inducing threads of her home-grown cloak and makes Wolf-Sauron drowsy and sluggish so that Huan can get the upper hand (paw?). Huan is triumphant, and finally gets Sauron by the throat. Morgoth’s lieutenant tries to shift forms to wriggle free but the wolfhound’s jaws are too strong. As Sauron considers departing his body in spirit form to effect his escape, Lúthien gives him “counsel.” Sure, he could go all Pac-Man ghost-like and fly back to Morgoth like a whiny baby, but if he does…

‘There everlastingly thy naked self shall endure the torment of his scorn, pierced by his eyes, unless thou yield to me the mastery of thy tower.’

Oh snap! Remember, Lúthien is the ultimate “flower” of Elvendom and here she’s all up in the face of Sauron—you know, future Lord of the Black Land, the Lidless Eye, the Big Bad Mofo of Mordor (I may have made up that last one). She says she’ll let him go if he gives up mastery of Tol-in-Gaurhoth. Sauron, sobered by what she’s saying, agrees to her terms to save his literal skin. He relinquishes his tower, assumes the form of a vampire—a demon bat in Tolkien’s world—and flies off, ending his part in this tale. The future Dark Lord of the Third Age, beaten down by a pretty Elf girl and her dog. Hell yes.

And thus the damsel our hero Beren is rescued on his own mission! “Thank you, Princess. But our mortal Man is in another castle!” Lúthien finds him in the dungeons and draws him back up out of his despair with the power of her voice. They bury Finrod on the island, which actually used to be part of his own kingdom. The quest for the Silmaril remains unfulfilled, but they need time and rest to recover from their many hurts. Beren and Lúthien get to spend a few months together in peace. Huan, ever faithful, even goes back to his master Celegorm the Seriously Undeserving. The Elves of Finrod’s kingdom lament the death of their lord but—and I feel like this sits near the heart of the story—they also proclaim “that a maiden had dared that which the sons of Fëanor had not dared to do.” In this, there is a snub of the two jerky Elf lords and accolades for Lúthien. It’s not expected that a woman challenges such terrible foes, especially the “Daughter of Flowers,” but it also obviously pleases the Elven populace to have seen this.

After a short time, Beren is resolved to continue his quest. But being a bit dense, he tries to drop our heroine back home first… as if she wasn’t crucial to his quest’s success? And being who she is, Lúthien isn’t having it:

‘You must choose, Beren, between these two: to relinquish the quest and your oath and seek a life of wandering upon the face of the earth; or to hold to your word and challenge the power of darkness upon its throne. But on either road I shall go with you, and our doom shall be alike.’

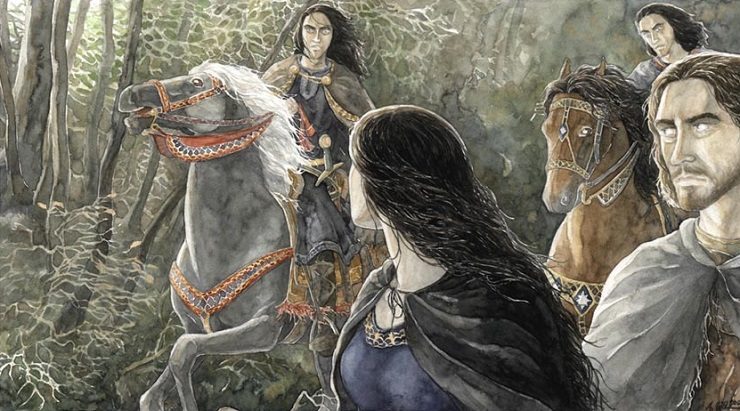

Heavy and romantic words in a story already full of them. But before they go on, in charges Celegorm and Curufin! The brothers had spied them in the woods and sought revenge for wounded pride and imagined slights. These guys are elitist, self-entitled Elf privilege personified. Celegorm tries to run Beren down on his horse, while Curufin grabs Lúthien up onto his. But now that he’s rested up, our hero employs the Leap of Beren—which, yes, Tolkien actually uses as a proper noun, for it was “renown among Men and Elves”—and dodges one brother while bearing the other off his horse. Lúthien is thereby flung into the grass, stunned. Just as Beren is about to strangle the life out of Curufin, his brother Celegorm recovers and goes to run Beren through with a spear.

And that’s when Huan, who’s been trotting along with his master this whole time, has had enough of his master’s shenanigans. He foils Celegorm’s attack and scares off his steed. Lúthien demands that Beren spare Curufin because, like her mother, she is the moral compass among all these hot-headed males. Interestingly, Lúthien has shown that she falls under the power of other Elves more easily than any monster of Morgoth, for at heart she is too trusting of kin. Beren honors his lady’s request, but Beren deprives the jerkwad of his gear and takes as recompense an elegant knife named Angrist. This sweet blade had been crafted by the same talented dwarf who forged the famous sword Narsil—as in, the very blade that would later cut the One Ring from Sauron’s hand.

The two sons of Fëanor curse Beren and then start off. Quite suddenly, though, Curufin grabs his brother’s bow and from afar shoots an arrow at Lúthien. WTF? When Elf attacks Elf it’s an uncommon travesty, but this is just the sort of evil with which Morgoth has infected Middle-earth by this point. Huan snatches the arrow out of the air with his mouth—who’s a Good Boy?—but Curufin shoots a second time. This time is it Beren who steps in front of Lúthien and accepts the hit. Down he goes with the Elf’s arrow in his chest. Huan chases off the brothers then fetches herbs to help Lúthien tend to Beren’s terrible wound. He’s totally her dog now.

“[B]y her arts and by her love” Lúthien heals Beren. They come to the borders of Doriath again, but because he still doesn’t get it, Beren sneaks off early in the morning to continue his quest alone. Tolkien doesn’t say so, but Lúthien probably rolls her eyes when she wakes up. It’s a testament to her love for Beren that she takes this is stride and simply goes after him with the Best Dog Ever beside her.

But first they stop by the mountain pass where they battled Sauron. Because they’re going deeper into enemy lands they know they’ll need a disguise. Huan takes “thence the ghastly wolf-hame,” or skin, of Draugluin the dead werewolf and he puts it on like clothing. Being from Valinor, a blessed realm untouched by Morgoth’s evil, Huan probably normally has a very shiny coat and wins Best in Show every time, but that’s much too conspicuous in evil lands. The foul skin of a werewolf sire solves that! Lúthien, meanwhile, is far too pretty to walk casually about, either. Therefore she puts on the “bat-fell of Thuringwethil” as her disguise. Thuringwethil was a vampire messenger, and though her demise is never actually mentioned in the tale, she was presumably slain among the other minions of Sauron. So with Huan at his most fiendish, and the lovely Lúthien looking more goth than ever with “great fingered wings […] barbed at each joint’s end with an iron claw,” they continue on unhindered.

Across a dark forest “filled with horror,” they finally catch up to Beren. This freaks him out at first because of the Halloween costumes they’re wearing. Once they reveal themselves to him, though, he is dismayed. Why? Because his beloved Lúthien, whom he loves above all else, was once again in peril just being there. And that’s when Huan, who has had enough of this fool’s stubbornness, tells it to him straight:

‘From the shadow of death you can no longer save Lúthien, for by her love she is now subject to it. You can turn from your fate and lead her into exile, seeking peace in vain while your life lasts. But if you will not deny your doom, then either Lúthien, being forsaken, must assuredly die alone, or she must with you challenge the fate that lies before you—hopeless, yet not certain.’

After probably saying, “Wait, you can talk?!” (and to which Huan would have answered, “Only three times in my whole life, as it happens”), Beren concedes at last. The maiden he loves was going to be there with him to face the greatest of all enemies, and he just has to get used to it. Huan also tells them that he can go no further on their road together—possibly because he is tired of being a fifth wheel on this, the weirdest date of all time. This also frees up the Draugluin skin suit, which Beren puts on. So Beren with his badass/gross werewolf-skin and Lúthien with her sexy/gross bat-skin set off on the last leg of the quest. Interestingly, these forms are more than mere cloaks, though; such were the arts of Lúthien and/or the powers of the slain monsters themselves that donning the skins transforms their wearers—at least in part. “Beren became in all things like a werewolf to look upon, save that in his eyes there shone a spirit grim indeed but clean.” And Lúthien in her vampire form could actually fly.

It’s so freaking awesome. In an essay, Tolkien scholar Thomas M. Honegger wrote that this element of the tale seems to borrow from Guillaume de Palerne, a French romance poem from the thirteenth century—which Professor Tolkien would be more than familiar with—in which two young lovers escape an arranged marriage by donning the skins of polar bears at the behest of a prince-turned-werewolf. When he doesn’t invent an idea out of whole cloth—and it’s no secret he drew from old mythologies and literature—Tolkien repurposes them.

By their servant-of-Morgoth cosplaying, Beren and Lúthien come “through all perils” far to the north to the hellish gates of the Dark Lord’s lair at Angband which I imagine makes Mordor seem like a holiday destination. Travel brochures would highlight Angband’s serpent-filled chasms, its carrion fowl screeches in the sky, and the thousand-foot cliff wall rising above it. But here our heroes are stopped in their tracks when they see a creature guarding the gate like Cereberus at the gates of Hades.

It is Carcharoth, the Red Maw, the Jaws of Thirst, the biggest and meanest of wolves, who’d been sired by Draugluin, likely bred for the express purpose of battling Huan. Carcharoth had been fed by Morgoth’s own hand the flesh of Men and Elves until “the fire and anguish of hell entered into him, and he became filled with a devouring spirit, tormented, terrible, and strong.” (He’s also the last supernatural canine in this story, I promise.) Yet Huan isn’t here this time, just Lúthien and Beren. Carcharoth, despite his thirst for violence, is merely puzzled by their presence, unsure of who they are. They look odd. And heyyyy, that wolf-skin looks kind of familiar—

Lúthien takes advantage of the dread wolf’s vexation, throws back her vampire-skin, and casts a spell of sleep upon him. Down he goes, snoozing like Fluffy outside the hiding place of the Philosopher’s Stone. They enter Angband, descending its many dark stairs, and “together wrought the greatest deed that has been dared by Elves or Men.” For here at long last they step into Morgoth’s “nethermost” hall, a place of death and torment, where the Dark Lord himself is sitting upon his throne with his court of fell monsters around him.

Normally this is where the male hero draws his sword and boldly confronts the villain. Not here! Beren is immediately cowed by Morgoth’s majesty, crawling low to the floor at the Dark Lord’s feet like the dog he’s become. Lúthien, meanwhile, is “stripped of her disguise by the will of Morgoth,” though she stands her ground and willingly endures his vile gaze.

In the book Perilous and Fair: Women in the Works and Life of J. R. R. Tolkien (a worthwhile read, edited by Janet Brennan Croft and Leslie A. Donovan), scholar Cami D. Agan addresses this vital development. “Chillingly, this moment appears to enact [Lúthien’s] description of Sauron’s impending humiliation.” It’s serious business to stand vulnerable before such a fiend; “physically and metaphorically naked before the gaze of Morgoth, Lúthien is threatened with objectification, rape, and perpetual torment. However, Lúthien retains her identity, names herself, and thus solidifies her power. In naming herself, Lúthien claims equal standing with Morgoth himself; she is unafraid, ‘not daunted by his eyes,’ the very eyes that Sauron fears to endure in defeat.”

As the embodiment of pride in Middle-earth, Morgoth is overconfident. He allows her to address him, vulnerable as she appears. So Lúthien offers to sing for him “after the manner of a minstrel.” He buys it, expecting that he’s fully in control of the situation. But as Agan writes, “Lúthien appears to offer ‘service’ out of a position of weakness—and this is what Morgoth ‘sees’—when in reality she has worked through his bodily desire to create a space and time wherein she might take mastery of Angband.”

Morgoth is, like most, captivated by her beauty. He is not immune to its power, for he’d been a being of beauty himself once, back when he was greatest of Ilúvatar’s celestial team. Lúthien artfully uses Morgoth’s own lustful fascination against him. She slips into the shadows of his chamber and begins a new “song of such surpassing loveliness, and of such blinding power,” like some epic-level D&D bard spell. Morgoth is utterly dumbfounded and blinded. The crown on his head with its three Silmarils blazes with light, stirred by Lúthien’s power, and under its weight Morgoth is bowed down. She uses her cloak—you know, the one she wove of hair from her own head—to “set upon him a dream, dark as the Outer Void where once he walked alone.” Morgoth collapses to the ground, the crown sent rolling across the floor, and his entire court falls into slumber with him.

A touch from Lúthien awakens the now-sleeping Beren—remember him? This being the pivotal moment in his quest, he throws off the wolf-skin and uses the iron-slicing knife Angrist to cut free one of the Silmarils from the fallen crown. Realizing that nobody, but nobody, will get this chance again, Beren decides to try for all three gems, but the knife breaks and a shard goes flying and—as Murphy’s Law apparently dictates even on Middle-earth—strikes the sleeping Morgoth in the cheek. The Dark Lord begins to stir, Lúthien and Beren make like Entwives… and leave. Swiftly!

While the menagerie of monsters isn’t quick to awaken and give chase, Carcharoth is waiting for them at the door, wide awake now and angry. Lúthien is too spent from her struggle against Morgoth to deal with the big bad wolf again, but Beren has a Silmaril in his hand and it blazes forth with the light of the Trees of Valinor. He thrusts the gem out, hoping to frighten away the wolf with its power, “‘for here is a fire that shall consume you, and all evil things.'” But Carcharoth, channeling Fenrir the wolf of Norse mythology from which Tolkien undoubtedly drew inspiration, chomps down on Beren’s outstretched right hand and bites it off, Silmaril and all.

Then swiftly all his inwards were filled with a flame of anguish, and the Silmaril seared his accursed flesh. Howling he fled before them, and the walls of the valley of the Gate echoed with the clamour of his torment.

So off runs the Silmaril-stricken wolf, with Beren’s hand in his belly, burning with holy flame. It doesn’t kill him, just drives him mad with rage and he kills everything in his rampage. Beren, meanwhile, falls, poisoned by Carcharoth’s venom. Beren is dying once again, but Lúthien draws out the venom with her lips as if it were a mere snake bite and not a gaping severed hand wound. This—this here!—is the badass princess I’m talking about, and it’s just what I’ve come to expect from her.

Just another day in this romance, though! Boy meets girl. Girl puts evil demigod to sleep. Boy steals demigod’s gem. Demigod’s dog bites off boy’s hand and poisons boy. Girl saves boy again by sucking poison out of boy’s bloody stump.

Lúthien uses the last of her power to bind Beren’s wound, but Morgoth’s horde is soon to overcome them. All seems lost… except for a story device familiar to readers of The Lord of the Rings. Lúthien and her boyfriend are spied from above and saved by Thorondor, Lord of the Eagles, and two of his vassals, who were actually flying over the region specifically in search of them. Does it seem random, or dumb luck? Nope! Huan, the most exceptional dog in all the world, had asked all his animal friends to keep an eye out for these two specifically. See, the Eagles are a cut above the animals of Middle-earth, having been placed in the world by the Valar, like Huan himself, specifically to aid the enemies of Morgoth.

Beren and Lúthien are carried far from Morgoth’s lands and dropped off at the border of Doriath. Beren languishes and nearly dies from his horrendous wound, but he pulls through, waking to the singing of his beloved Tinúviel. And as many of Tolkien’s characters are wont to do, he receives another name. Beren still goes by Beren, but now he’s also Erchamion the One-Handed. The two lovers share in a time of peace and togetherness again, albeit with one fewer hand between them, but the quest remains unfulfilled, under a technicality: the Silmaril he was to retrieve is actually inside a rampaging wolf monster.

Lúthien is actually fine with this; she’s proven by now that she’s nobody’s fool and she’s through worrying about her dad’s expectations. She is content to elope, having been to literal Hell and back, and is content to leave the quest alone. But Beren still wishes to do right by her father and, more importantly, by the honor of his word. When the two do return to Thingol’s court, the Elf king isn’t exactly happy to see Beren still alive. Beren fesses up that he doesn’t have the promised Silmaril yet. He shows Thingol his stump and, for crying out loud, he gives himself another epithet. Now he is also Camlost, the Empty-Handed. Seeing this, and hearing the hardships of their adventure in full, Thingol actually softens up at last and finally consents to their marriage.

And so, before the throne of Doriath, “Beren took the hand of Lúthien.” Which, frankly, seems like an insensitive way for Tolkien to have worded it, under the circumstances. So hey, Beren gets the girl! But actually, Lúthien got the boy first. He kind of had her at “Tinúviel.”

Now that the wedding has happened, Thingol organizes a hunt for Carcharoth because he’d been terrorizing the land in his agony and he did still have that elusive gem that everyone wants. Huan, of course, is the first to volunteer, and Beren, Thingol, and a few other significant Elves sign on as well. Lúthien, notably, does not go, for a “a dark shadow” falls over her for what I can only imagine is the weight of her newly-bestowed doom. She has just been hitched to a Man and that’s never happened to an Elf before. It’s unclear what the consequences will be—but in truth, the prospect of real death falls upon her. Men like Beren live with death close at hand at all times, but for Elves it is, as mentioned earlier, quite a revelation to digest.

Carcharoth is eventually tracked to the banks of a big river, where he has paused to drink, for its sweet waters are the only thing that can temporarily relieve the burning Silmaril-based indigestion he’s been suffering. After a game of cat and mouse with the hunters, the great wolf leaps at Thingol. Beren jumps in the way, saving his new father-in-law, and gets mauled horribly by Carcharoth. Then the wolf is tackled by Huan and the two engage in a titanic final battle that churns the earth and “choked the falls” of the river itself. The wargs of the Rings trilogy had nothing on these two.

At last, Huan slays Carcharoth… but his own prophesied death at the jaws of the greatest wolf comes to pass as well. Huan collapses beside Beren and speaks his final words, saying farewell. Beren is too gravely wounded and too grieved to speak, because honestly, the magical heavenly dog was always too good to be true, and now he was gone. He had done more than his part in helping the two lovers. Man and Elf’s best friend.

Carcaroth is cut open and the Silmaril is recovered! Then—finally—Thingol is satisfied that the mission has been accomplished. Yet his own victory is hollow and “full-wrought” because he’s still losing his daughter to this brave and foolish Man… and at this point said Man is dying, for real this time. By the time Beren’s body and Huan’s corpse are brought back to Elven lands, Lúthien is there to receive them. She embraces Beren, and he dies.

The end.

Nope again! As if this love story wasn’t already its own twisty tale of magic blades, holy gems, and monster skins, here is where one Man and one Elfmaid really break the rules. Because Lúthien asked him to—seriously, because she just bade him to—Beren’s spirit lingers in the halls of Mandos before passing on to wherever it is that the spirits of Men go. Mandos is the archangelic being whose judgments shape the world, and his halls are essentially the waiting room to all the mysteries beyond the veil. And here Beren waits because he finally really listened to her.

Lúthien herself shows up to meet him there, leaving her body lifeless behind her on Middle-earth to the great despair of her family. And then she sings her “most sorrowful” song to Mandos. Aside from bumming him out big time, it’s obviously an earworm of great power:

Unchanged, imperishable, it is sung still in Valinor beyond the hearing of the world, and listening the Valar are grieved. For Lúthien wove two themes of words, of the sorrow of the Eldar and the grief of Men, of the Two Kindreds that were made by Ilúvatar to dwell in Arda, the Kingdom of Earth amid the innumerable stars.

Lúthien is not only a participant and heroine of this story that’s so central to Tolkien’s world, but she also sets precedence for the union of the races of Man and Elf thereafter. Her lament before Mandos is a butterfly effect for events to come. Moved by her song, and knowing he cannot change the rules, Mandos thinks about what he can do. He turns to Manwë, the King of the Valar (and brother of Morgoth!), who does have the authority to at least pull some strings in the heavens. Manwë therefore gives Lúthien a choice:

- (A) Dwell in paradise among the Valar, but without Beren, and there she would forget all worldly griefs.

- (B) Return to Middle-earth with her husband and join him in a mortal’s uncertain life, where nothing, not even joy, can be promised. (Sound familiar, fellow humans?) In time, true death would come them both.

- (C) Kidding, there’s no C.

She chooses B, forsaking the immortality of Elves and all mystical ties to her people. Lúthien and Beren do live on for a time, resurrected, and able to visit those they love who still lived. And because she is a mortal now, Lúthien knows her parting with her parents will be exceedingly painful. In the mysterious afterlife of Tolkien’s legendarium, it is at least clear that mortals and immortals go their separate ways when all is said and done. Curiously, the Silmarillion’s narrative presents death as a gift to Men, something the Elves at times do envy, but that is another topic for another day.

Eventually Lúthien and Beren retire in a scenic island called Tol Galen, but no one ever sees them again, nor know where they eventually died. Yet they do have children. Elrond will be their great-grandson, and his daughter, Arwen Undómiel, will face the same choice Lúthien had. In some ways, Arwen’s life mirrors Lúthien’s in both function (she marries a Man and chooses mortality to be with him) and form (Arwen looks a lot like her). The very concept of the Half-elven—those born of the union of Men and Elves—comes with its own policy, a new rule that requires such individuals to decide whose fate their line would bear. Elrond, for example, chooses the immortality of the Eldar, but is unable to prevent both his twin brother and his daughter from choosing the doom of Men. Yet even those who fade away lived remarkable and lengthy lives. Elros, brother of Elrond, would become the founder of Númenor and Arwen, of course, would become pivotal in the life of Aragorn, who in turn is pivotal in the defeat of Sauron in the Third Age.

So ultimately, Beren and Lúthien become a kind of archtype for their respective races. Yet in the end this is still mostly a love story, not an action story. They are star-crossed lovers in a way that makes Shakespeare’s Veronan teens just a summer fling. Sure, Romeo and Juliet defy their rich Italian families to hook up. Tristan and Isolde wade through some feudal red tape for their passion. Catherine and Heathcliff just pine and brood over each other on the English moors. There are a lot of famous lovers in classic literature and many of them are worth reading about for the sheer passion and poetry of it. But a lot of them—dare I say most of them in the mythological or fantasy variety—also include a swooning damsel who is either rescued or “won” by their men. Even Buttercup in the otherwise awesome The Princess Bride mostly just cries and gets upset while Westley and his friends do all the work. But “Of Beren and Lúthien” is a tale in which the lovers save each other; neither can succeed on their own but together overcome all obstacles (with the help of their dog and their friends), and in the end she is a heroine who chooses to be with her beloved forever and share his fate… whatever that may be.

I think Beren’s great. He’s a hero’s hero without needing to be womanizing or blustery. We know him, because it’s easy to imagine he’s a lot like Aragorn. But Lúthien, to the casual Rings reader, is not as familiar in one woman. She’s as spiritual as Galadriel, as valorous as Éowyn, as comforting as Arwen. She’s the memorable one here—a heroine of mettle and volition, a woman who escapes the chains imposed on her, makes her own decisions, commands enemies and friends alike, stands boldly against evil, and yet is the voice of healing and mercy when that is needed instead. She may seem like a superhero at times (to be fair, the Silmarillion doesn’t spend much time talking about everyday people), but she is still at times naive and flawed. She falls for a rugged, sweaty, homeless, and mortal ranger type and that gets them both in a heap of trouble with her people.

So boy meets girl. Boy falls in love with girl. Boy and girl go on a crazy long adventure, upstage everyone, and live in mixed sorrow and happiness until the end.

Then, of course, it’s also a very personal tale for old J.R.R. and his bride Edith, who once gave him inspiration “in a wood where hemlock was growing,” where her dancing begat a legend.

Jeff LaSala is a freelance writer who once published, among others, an article in Dragon magazine called “D&D Love Stories” because courtship that involves monsters and magic is better than any romantic comedy. He wrote some sci-fi/fantasy books, works for Tor, and wanders the roads of life together with his wife and son. “And whither then? I cannot say.”