Welcome to the weekly reread of Camber of Culdi! Last time, Coel did some off the cuff scheming when he found Cathan murdered by the king, but Camber discovered some of the truth thanks to a loyal watchdog.

This week Imre finally makes his move against the MacRories, Camber and company do their best to stay ahead of him, and a certain dashing pair abducts a certain cloistered monk and carries him off to a fate that may, or may not, be worse for him than death.

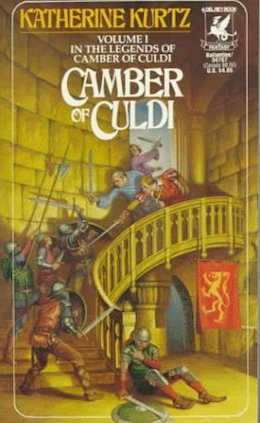

Camber of Culdi: Chapters 13-15

Here’s What Happens: In Chapter 13, there’s a lull in the race to the finish. The king hasn’t made a move. The king’s guards are still in the hall. Camber and Evaine are surreptitiously prepping for their escape. Elsewhere, principals in the game are doing much the same. One of them happens to be drawing conclusions about the Draper family.

Imre meanwhile is absolutely miserable and taking comfort from Ariella. Coel Howell ventures into Ariella’s chambers with his latest findings: he knows what Joram was looking for among the birth records, but not why. He discusses the Drapers with the king and Ariella, trying to figure out what’s so important about them.

This goes on for some time. Imre is the most perceptive, and he’s the one who connects Joram’s investigations of birth records with Rhys’ explorations in the royal archives. He wonders who Daniel Draper was before he was a merchant. Ariella makes the inevitable and perilous leap: it’s a conspiracy against the Festils, and it may be connected with the Haldanes.

Coel is way behind them, and blown away by their conclusions, but those happen to fit into his plans. He asks if the king wants Joram and Rhys interrogated. Imre, in response, has another psychotic break. He wants the whole family arrested. Now. Tonight.

The arrest warrant reaches Caerrorie that evening. Guaire gets to the family quarters first. Camber answers the door, concealing what’s inside. He plays for time, then Jamie pushes past Camber, and he and Guaire attack the king’s men while Camber, Rhys, and Joram exit via Portal.

We see this sequence through Guaire’s eyes. He’s busy fighting and not paying much attention to the Deryni pyrotechnics. Camber is equally busy getting the women and children out. Guaire is wounded, but Camber rescues him. They all escape, Jamie included.

Chapter 14 shifts to Rhys and Joram, who are riding up to St. Foillan’s. The weather is horrendous (which is a theme in this book). They have a plan, but we’re told in detail why it might not work. We’re also told that they can’t talk either verbally or telepathically while they’re infiltrating the abbey, because a Deryni might happen to overhear.

While the blizzard intensifies, they get over the wall with rope and hook, and make their lengthily described way through the multiple spaces inside. Rhys is a nervous wreck. Joram is relatively cool and suitably dashing.

Inch by inch and page by page and space by space, they make their way toward their quarry. They’re almost caught, which takes some considerable time. Inch…by…inch…

And finally they find Cinhil in his cell, and Rhys nearly blows the whole operation with a well-intentioned mind-touch. He’s trying to wake the man gently and ends up causing him to panic.

The extraction gets very physical very fast. Rhys tries to use Healer powers, but Cinhil doesn’t respond. Rhys has to hit him with a combination of carotid pressure and Deryni mind-whammy.

Cinhil is now unconscious, and they carry him out. There are monks everywhere, and breathless narrative to go with. Finally the inevitable happens: the statutory doddery old monk who wants to stop and talk, and has to be whammied big time. They hit him with an amnesia spell (and we get a snapshot of the results) and finally manage to get out, with a spate of omniscient narrative and passive voice (and a snapshot of what they have to do and when and where they have to go).

Chapter 15 continues in this vein, with somewhat of a letdown as we’re told “they were never in any real danger, …for news travels slowly across winter-bound Gwynedd.” Which is pretty accurate in medieval terms, but hello, what happened to narrative tension?

I think this is trying to be a history written by someone in Kelson’s time. Trouble is, the story loses tension and frankly readability, the more passive and distant the narration gets.

The big deal here is that while our heroes are conveniently free of danger or pursuit, they have a chance to get to know Cinhil. Rhys is the first to notice that the prisoner has come to and is observing them. Rhys clues Joram in—Joram is asleep in the saddle—and Cinhil wants to know who they are.

Joram answers, and calls Cinhil “Your Highness.” Cinhil reacts badly. They camp, and he continues to refuse their attempts to treat him like a king. Joram lays the whole of his pedigree on him, both the false one and the true.

Cinhil flatly rejects his royal heritage. He begs them, humbly and gently but persistently, to send him back to his abbey. Joram and Rhys meanwhile have a plan that Joram is not happy about at all.

Both Joram and Cinhil keep pushing, for and against. Joram lets Cinhil loose after he promises not to try to escape. Once he’s free, he collapses in tears.

This is obviously going well.

When they go on, they do so in silence. Rhys is trying to read Cinhil and failing. Cinhil is not in good shape either for riding or for accepting his royal heritage. Finally Rhys takes the only way out he can think of: he drugs Cinhil to keep him docile and prevent him from escaping.

When Joram calls Rhys on it, Rhys tells Joram about Cinhil’s powerful natural mind-shields. Rhys says he’s sure he can break them down with Camber’s help, but meanwhile he’s opted for the quick and dirty.

They revise their plan to get the groggy captive into Dhassa and through the Portal with as little drama as possible. Joram teases Rhys about playing “the treason game.” Rhys begs him not to use that word.

Meanwhile, back at the abbey, our omniscient narrator is back on the job, telling us how long it takes for the monks to realize Cinhil is gone. Then we’re told in excruciating detail how the monks find two robes missing, and how they deduce the identity of the thieves, and how the abbot feels about it, and what he proceeds to do about it, and what the eventual consequences of those actions are. That includes a scene-shift to Valoret, where the vicar general of the order meets with the archbishop to discuss the situation.

They have, by this time, concluded that Camber is involved. The archbishop is an old personal and family friend. He and the vicar general speculate at considerable length about Camber, Rhys, Joram, the Michaelines, and the circumstances of Cathan’s death. It’s an open secret that the king did it.

After the vicar general has been dismissed, Archbishop Anscom sits alone and in distress. He knows who “Brother Kyriell” is. That was Camber’s name when he studied for the priesthood.

And I’m Thinking: Kurtz is a far better writer when she’s galloping along telling adventure tales than when she tries to get all high-epic-y and serious-historical-y and passive-voice-y. These chapters are heavy on the latter, to the point of sinking under their own weight. They’re also heavy on the kind of conversations that one sees in detective novels, where characters discuss the mystery at great length, line up all the evidence, debate the various aspects, and either arrive at a conclusion or agree that the matter needs further investigation.

Imre is fast becoming my favorite Kurtz villain. He’s so complicated and so unstable, and somehow he manages to be sympathetic in that he doesn’t mean to do the awful things he does. He just can’t help himself.

Why, yes, I do have a soft spot for complicated villains who can’t help themselves. I’m a big Cersei fan, too.

I’m still finding Cinhil much less annoying than I did the first time around, and Camber and company much less sympathetic. They’re hardline Machiavellians and by God they are going to do what they are going to do, and never mind how anyone else feels about it.

Cinhil is happy with his vocation. He belongs in the abbey. And he’s been ripped out of it, slammed into a situation he never wanted or chose, and there’s no way his captors are going to let him go.

This was a revelation to me at the time, and one of the inspirations for my nonhuman monk in The Isle of Glass. The profound disconnect between genuine vocation and secular necessity.

Camber really is a cold bastard. All the Deryni are. They use humans like cattle. They decide what’s right, and they go out and get it. Regardless of the consequences.

Then there’s poor gentle Cinhil, who never wanted a Destiny. But the Deryni don’t care what he wants, or what anyone else wants, except themselves.

Interesting that I’m reacting so strongly this time around. When I first read the book, I thought Camber was magical and mystical and quite wonderful. Now I find him almost repellent.

The younger generation don’t bother me as much. They’re all under his influence, and they’re trying their best to do right according to his parameters. I can’t fault them for being good servants or obedient children.

In the meantime I’m noticing that Kurtz recycles sequences—the secret tunnel and the page with the horses in the previous set of chapters, for example. And she recycles characters: Joram is Morgan Lite, Camber is what Stefan Coram might have been if we’d been given any part of that story before the end.

I notice Guaire is playing the Derry-got-hurt role, so probably will get healed next, since Rhys is a Healer. I also notice that the villains in this book are more nuanced than the ones in the first published trilogy. They’re written better and for me they play better.

Kurtz continues to be really strong on the faith side of things—portraying real and believable clerics. The sequence with Archbishop Anscom is a plot-dragger, but he is a lovely example of the sympathetic prelate. Both of the sequences in the abbey are written with loving detail, however prolix and unnecessary most of it is. Those scenes are author darlings, I think. As a reader I kept skipping and skimming and wishing she’d just get to the point, please. As a writer I see the love in every consciously crafted sentence.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, a medieval fantasy that owed a great deal to Katherine Kurtz’s Deryni books, appeared in 1985. Her most recent novel, Forgotten Suns, a space opera, was published by Book View Café in 2015, and she’s currently completing a sequel. In between, she’s written historicals and historical fantasies and epic fantasies, some of which have been reborn as ebooks from Book View Café. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed spirit dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.