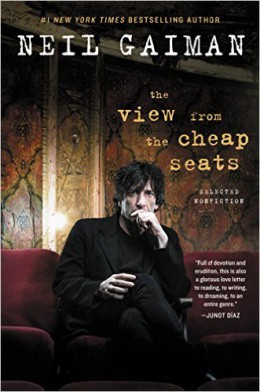

In what would quickly become his most viral work to date—the 2012 commencement speech at the University of the Arts—author Neil Gaiman gave a piece of simple, if sprawling, advice: “Make interesting mistakes, make amazing mistakes, make glorious and fantastic mistakes. Break rules. Leave the world more interesting for your being here. Make good art.” And from an author as prolific, as adventurous, and (as I’ve learned) unabashedly optimistic as Gaiman, this suggestion is as sincere as it is solid. In his new nonfiction collection, The View From the Cheap Seats, readers will find over two decades of Gaiman’s rapt love and encouragement of good art. They’ll find speeches, essays, and introductions that overflow with nerdy fervor, and that use the same graceful, fantastical turns of phrase that define the author’s fiction. They’ll find good art, for sure, and they’ll also find Gaiman’s own explorations of good art.

I’m not sure that Gaiman would want to call his work here cultural criticism, but I’m going to go out on a limb and slap on the label, and I’m also going to say it’s some of the best of its kind. Debates about the role of criticism—who has the right to say what about whom and on what platform, and why it matters that they’ve said it—are almost as old as culture itself. And the line has always been blurry, too, between critic and creator, between fan and creator, and between fan and critic. The View From the Cheap Seats exists along these blurred lines, reveling in a world that is full of art and full of people talking about it, experiencing it, and creating it. We know Gaiman the author, but here is Gaiman the fanboy, Gaiman the journalist, Gaiman the boy that was raised by librarians. The View From the Cheap Seats is a book of conversations. It’s a book of kind words and big ideas, and yes, occasionally, it’s a book of recommended reading.

The book itself is organized by subject headings—from music to fairy tales to current events—but the distinction between these topics is, as with most subject headings, mostly editorial. Reflections on authors like Douglas Adams appear in multiple sections, as do some of Gaiman’s recurring, favorite refrains (namely, to support the the people that dedicate their lives to art, from booksellers to editors). In both cases, of course, it’s a refrain that’s worth repeating. What ties the collection together as a whole, though, is the ongoing tone—whether the essay was written in 1994 or 2014—of generosity and excitement. The “make good art” speech mentioned above is placed towards the end of the book, a move that I at first thought odd considering it was already published as a standalone art book. But the speech ultimately acts as a cornerstone for essay after essay of Gaiman praising the “good art” that made his own good art possible. His call-to-action is grounded by examples of the very interesting, amazing, and glorious mistakes that are the groundwork for our culture.

Taken as a whole, in one single gulp, the collection can sometimes feels like a series of Great Men (and Very Occasional Women) That Neil Gaiman Knows Personally. But on their own, each essay is a love letter to craft, to wonder, and to mystery. I recommend reading them as such, a piece here and there, spread out as you like. Reading the essays like this, I think, will help them maintain their rooted optimism. To be sure, there is something refreshingly positive about the collection. Even when offering criticism—as in his introduction to Jeff Smith’s Bone—Gaiman does so with the good humor of a man wanting more out of something he already loves, like a dog trying to unearth a skeleton because one bone wasn’t enough. I finished the collection wanting to revisit old favorites, fall in love with Dracula and Samuel Delany and Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell all over again. And I also came away with new recommendations—would you believe I’ve never listened to a full Tori Amos album?—taken fully to heart, not because Gaiman claims everyone “should” love these artists, but because his own enjoyment of them is so sincere and apparent.

I didn’t like or agree with everything Gaiman said in these essays, but I also don’t believe that this matters all that much. Just as he has brought a generosity and kindness to his subjects, so too do I think Gaiman invites his own readers to do the same: Here is this thing I’ve created, he seems to say; I hope that you enjoy it, or at the very least the one after that (or the one after that, ad infinitum). He’s said it before as an author, and now says it as a critic. Not, of course, that there’s much of a distinction. When it comes to making messy, fantastic mistakes, we’re all in this together.

The View From the Cheap Seats is available now from HarperCollins (US) and Headline Publishing Group (UK).

Emily Nordling is a library assistant and perpetual student in Chicago, IL.