“Court Martial”

Written by Don M. Mankiewicz and Stephen W. Carabastos

Directed by Marc Daniels

Season 1, Episode 14

Production episode 6149-15

Original air date: February 2, 1967

Stardate: 2947.3

Captain’s log. Following a severe ion storm, which badly damaged the Enterprise and killed Lt. Commander Ben Finney, the ship goes to Starbase 11 for repairs. Kirk reports to Commodore Stone, signing a deposition. Spock beams down with a computer log just as Finney’s daughter Jame shows up accusing Kirk of murdering her father. Finney was an instructor at the Academy when Kirk was a midshipman, and they became close friends—Jame was named after him—but a black mark on his record slowed his promotion prospects. Kirk himself was responsible for reporting the lapse that led to the black mark in question: when they served together on Republic, Finney neglected to close a circuit.

Spock’s log shows a discrepancy: Kirk put in his deposition that he didn’t eject the pod until the ship went to red alert, but the log states that he ejected the pod while still at yellow alert. Stone confines Kirk to the base pending a review board.

Kirk and McCoy go to a bar on the base, which is being patronized by several people from Kirk’s Academy class. None of them are thrilled to see Kirk, as they blame him for Finney’s death the same way Jame does. Kirk leaves the bar, disgusted at the lack of support, leaving McCoy to talk to a woman who walks in in civilian clothes: Lieutenant Areel Shaw, who describes herself as an old friend of Kirk’s (nudge nudge, wink wink, say no more).

Stone starts the inquiry. They encountered an ion storm. Finney’s name was next up on the duty roster to report to the pod to take readings. When the storm grew worse, Kirk had to jettison the pod once the ship had to go to red alert—he gave Finney all the time he needed and more, but he didn’t leave the pod.

Stone turns the recorder off, and offers Kirk a deal: accept a ground assignment, and it all goes away. But Kirk refuses: he was there, and he knows he didn’t eject the pod too soon, and he refuses to sweep it under the rug. Stone reminds him that no starship captain has been court-martialed before, but Kirk insists on it.

Kirk meets Shaw for a drink in the bar. Shaw, who is a lawyer for the Judge Advocate General, is the prosecutor for his case—something she doesn’t reveal until after she tells Kirk what the prosecution’s strategy will be and urges him to get an attorney, preferably the one she recommends.

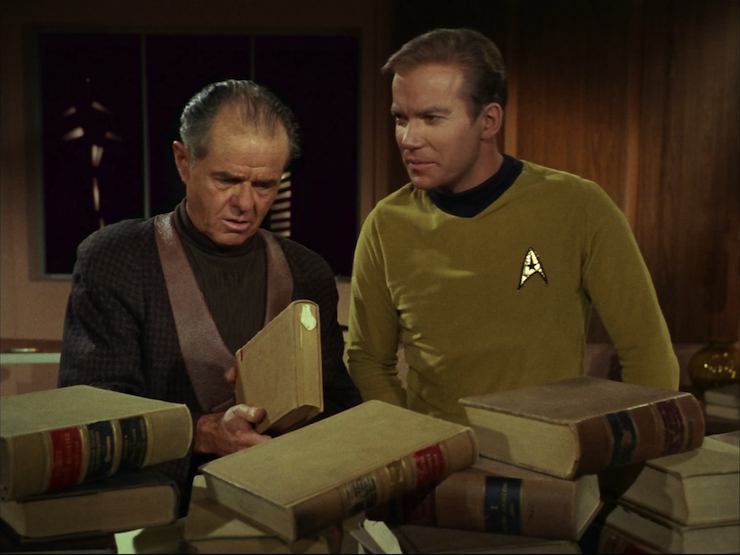

After risking her legal license by giving that advice, Kirk goes to his quarters to find the attorney in question: Samuel T. Cogley, who never uses a computer, preferring to use (a very large pile of) books. He feels that books give you a better understanding of the intent of those who wrote the laws. He is unclear on how that works, exactly.

The court martial starts, presided over by Stone, with a Starfleet administrator and two starship captains filling out the board. Kirk pleads not guilty to the charges of perjury and negligence, and Shaw calls Spock to the stand. He testifies that the computer could malfunction to account for this but that his mechanical survey of the computer shows no such malfunction. However, Spock believes it must be in error because he knows the captain and that Kirk would do no such thing.

Next is the Enterprise personnel officer, who testifies to Finney’s reprimand, and then McCoy, who testifies that it’s possible that Finney’s resentment of Kirk could be reciprocated by Kirk, possibly subconsciously.

Cogley doesn’t bother to cross examine any of them, instead calling Kirk to the stand. Kirk insists he took the proper steps in the proper order in order to keep the ship safe. Shaw then plays the bridge log. It shows that Kirk jettisoned the pod before calling for red alert. Even Cogley is starting to doubt Kirk’s memory of the event.

But then two things happen: Jame recants her blame and tries to convince Cogley to force Kirk to change his plea and take the ground assignment, and Spock beats the computer at chess five times. The first is an unusual change of heart for the daughter of a murder victim, and the latter is flat-out impossible if the computer’s working right.

Cogley puts forth a motion to adjourn to the Enterprise, because Kirk has been unable to face the primary witness against him: the ship’s computer. In the briefing room, Cogley questions Spock, who testifies to the chess snafu. Only three people aboard ship have the ability to alter the computer’s programming in such a way for that to happen—and also to, say, alter visual records. Those three are the captain (Kirk), the science officer (Spock), and the records officer (Finney). Kirk then testifies to the fact that he called for a Phase 1 search of Finney after jettisoning the pod, hoping that he left the pod but was too injured to report. Cogley points out that such a search presumes the target wishes to be found and isn’t deliberately hiding.

Kirk orders the ship to be evacuated, save for the members of the court (now reconvened on the bridge), Kirk, Spock, McCoy, Hansen, Uhura, and the transporter chief. Cogley also departs to fetch Jame, in the hopes that she’d get him to reveal himself if they couldn’t find him. Spock then activates a booster that will detect every sound being made on the ship, which hears the heartbeat of everyone on board. McCoy uses a white-noise device to blot out the sounds of everyone on the bridge, and then Spock cuts off the transporter room.

That leaves one heartbeat still going. Spock traces it to the engine room. Spock seals the deck and Kirk goes down to confront Finney himself. Finney is convinced that Kirk’s part of a grand conspiracy to keep him from getting his own command. He’s also deactivated the ship’s power—the orbit is decaying, sooner than expected. Kirk distracts him by telling him that Jame’s on board, and then they engage in fisticuffs until Kirk—shirt torn in a manly manner—is triumphant. Finney, broken and sobbing, tells Kirk where the sabotage was. Kirk yanks out some wires and Hansen and Uhura are able to pull the ship back into a standard orbit.

With no objection from the prosecution, Stone declares court to be dismissed. Kirk is exonerated, and Cogley then takes on Finney as a client. Shaw passes on a gift from Cogley to Kirk—a book—and from herself—she smooches him.

Can’t we just reverse the polarity? McCoy goes to a great deal of trouble to use a white-sound device (actually a microphone) to blot out the heartbeats of everyone on the bridge. Then Spock pushes three buttons to eliminate the heartbeat of the transporter chief from what they were hearing—so, uh, why couldn’t Spock just do the same thing for the bridge that he did for the transporter room????

Fascinating. Bitterly, Kirk tells Spock that maybe his next captain is someone Spock can beat at chess (we’ve seen Kirk beat Spock in “Where No Man Has Gone Before” and “Charlie X“). This, somehow, inspires Spock to try playing chess against the computer to discover that it’s been tampered with, a leap in logic that the Hungarian judge gives a 9.5.

I’m a doctor not an escalator. Shaw asks McCoy whether or not a particular series of events is possible, based on his expertise in space psychology. It’s a functionally meaningless question, and I always preferred how James Blish put it in his adaptation in Star Trek 2: “You keep asking what’s possible. To the human mind almost anything is possible.”

Hailing frequencies open. Uhura gets to again operate the navigation console once power is returned and she helps put the ship back in orbit. She previously did so in “The Naked Time,” “The Man Trap,” and “Balance of Terror.”

No sex, please, we’re Starfleet. We get the latest Woman From Kirk’s Past (latest in a series, collect ’em all!), following the unnamed blonde lab tech mentioned in “Where No Man Has Gone Before” and Noel in “Dagger of the Mind.” This time it’s Shaw, a Starfleet attorney who doesn’t recuse herself from Kirk’s court martial despite the conflict of interest in a former lover (whom she kisses when it’s over!) being the subject of the proceeding she’s prosecuting.

Channel open. “All of my old friends look like doctors. All of his look like you.”

McCoy bitching to Shaw about how Kirk gets all the girls.

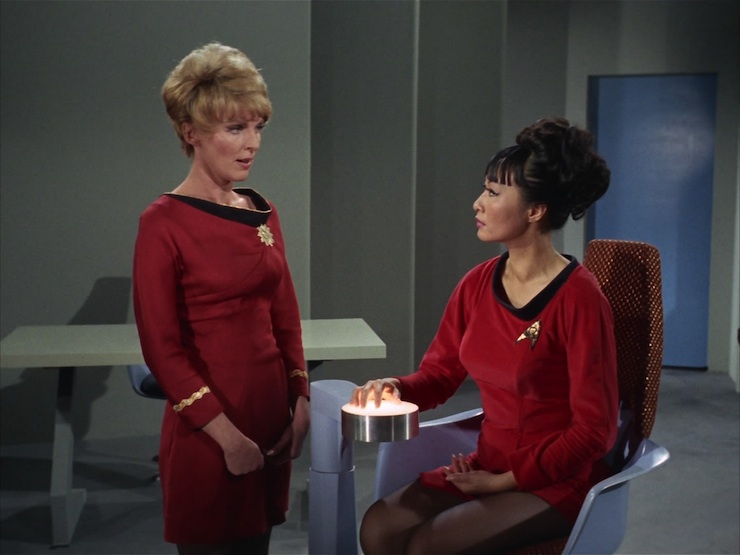

Welcome aboard. The great Elisha Cook Jr. puts in a unique turn as Cogley, while Percy Rodriguez brings a quiet dignity to the role of Stone. Joan Marshall plays Shaw, Alice Rawlings plays Jame, and Captain Midnight himself, Richard Webb, puts his resonant voice to good use as Finney. Recurring regulars DeForest Kelley and Nichelle Nichols show up as McCoy and Uhura, while Hagan Beggs makes his first appearance as Hansen the helmsman—he’ll be back in both parts of “The Menagerie”—and Nancy Wong plays the Enterprise personnel officer. Winston DeLugo, Bart Conrad, William Meader, and Reginald Lal Singh play various folks we see on Starbase 11.

Trivial matters: This episode was originally commissioned by producer Gene L. Coon as a cheap single-set episode, and Don M. Mankiewicz gave him a court martial story, intending it to take place entirely in the courtroom. However, the final version of the script required several new sets to be built, not to mention a matte painting of Starbase 11.

Speaking of that matte painting, it was used for the cover of an issue of Galaxy magazine being read by Benny Russell in the DS9 episode “Far Beyond the Stars,” and the cover story in that issue was “Court Martial” by Samuel T. Cogley.

This is the first episode to refer to the organization the main characters are part of as Starfleet and the top of the hierarchy being Starfleet Command. It’s also the first appearance of a starbase and our first commodore in Stone.

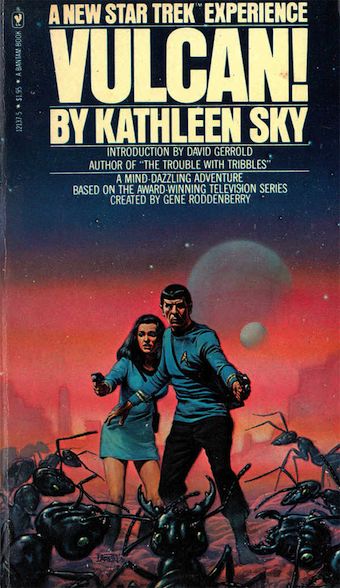

Stone is also the highest ranking African-American we’ll see in Starfleet in the series, and is an uncharacteristically color-blind bit of casting. (I should add that it’s uncharacteristic for late 1960s television in general. Trek itself actually had a good track record for such, including also Boma in last week’s “The Galileo Seven” and Daystrom in “The Ultimate Computer.”) Stone also appears in the novels Section 31: Cloak by S.D. Perry, Preserver by William Shatner with Judith & Garfield Reeves-Stevens, and Vulcan! by Kathleen Sky, as well as the second issue of Marvel’s Star Trek Unlimited comic by Dan Abnett, Ian Edginton, Mark Buckingham, & Kev Sutherland.

Stone is also the highest ranking African-American we’ll see in Starfleet in the series, and is an uncharacteristically color-blind bit of casting. (I should add that it’s uncharacteristic for late 1960s television in general. Trek itself actually had a good track record for such, including also Boma in last week’s “The Galileo Seven” and Daystrom in “The Ultimate Computer.”) Stone also appears in the novels Section 31: Cloak by S.D. Perry, Preserver by William Shatner with Judith & Garfield Reeves-Stevens, and Vulcan! by Kathleen Sky, as well as the second issue of Marvel’s Star Trek Unlimited comic by Dan Abnett, Ian Edginton, Mark Buckingham, & Kev Sutherland.

Cogley will be used again in several works of tie-in fiction, most notably the novel The Case of the Colonist’s Corpse by Bob Ingersoll & Tony Isabella, a Perry Mason-style courtroom drama that went so far as to be designed and printed in the style of the old Erle Stanley Gardner novels (down to the red dye on the edges of the pages). Cogley also appeared in Crisis on Centaurus by Brad Ferguson and the Khan comic book miniseries from IDW by Mike Johnson, David Messina, Claudia Balboni, & Marina Castelvestro.

Cogley and Shaw appeared together as a married couple in the tenth through twelfth issues of DC’s second monthly Star Trek comic by Peter David, James W. Fry, & Arne Starr, where they both jointly defended Kirk during the movie era.

The incident that led to Finney’s reprimand was dramatized in Michael Jan Friedman’s Republic, part of the My Brother’s Keeper trilogy. Finney also appeared in Renegade by Gene DeWeese, which served as a sequel to this episode. His daughter Jame plays a large supporting role in the DC Star Trek graphic novel Debt of Honor by Chris Claremont, Adam Hughes, & Karl Story, as well as its sequel in Star Trek: The Next Generation Special #2 by Claremont, Chris Wozniak, & Jerome Moore.

One member of the court martial board was Captain Nensi Chandra; Chandra was also seen in the alternate timeline of the 2009 Star Trek, also sitting in judgment of Kirk, as part of the board that investigated Kirk’s cheating on the Kobayashi Maru scenario. Another member of that board was Lieutenant Alice Rawlings, named after the actor who played Jame.

In his adaptation for Star Trek 2, James Blish explained that the pod draws in radiation from the ion storm and that when it builds up enough to be dangerous to the ship, it has to be jettisoned, which is also when red alert is called for (though in the prose version, it’s red and double-red alert, which is probably from an earlier draft of the script).

This episode provides both Kirk’s and Spock’s serial numbers as well as the various citations and medals they’ve received, though we don’t get all of Kirk’s.

To boldly go. “I speak of rights!” One of the dangers of doing rewatches of shows you grew up watching, or at the very least haven’t watched in a very long time, is that you run the risk of your opinion changing. This also can happen when one views the episode with a more critical eye, knowing you have to write a blog post about it.

I actually have really good memories of this episode, from McCoy’s old-friends line to Elisha Cook Jr.’s charismatic performance as Cogley to Richard Webb’s magnificent voice as Finney.

But watching it in preparation for this rewatch made me realize that the episode really doesn’t make any sense—even less so than the usual television portrayal of courtroom procedure, which is usually dreadful. And unlike, say, the procedural screw-ups of TNG‘s “The Measure of a Man,” these factors do actually sink this episode into mediocrity.

Part of my problem is a personal bugaboo. Ever since I became the editor of a line of monthly Star Trek eBooks in 2000, a gig that lasted until the line came to an end in 2008, I’ve constantly had to deal with people who are never happier than when they’re dismissing eBooks as yucky and waxing rhapsodic about the awesomeness of codex books and how they need the tactile and olfactory qualities of a book. In fact, those folks would often cite Cogley as their patron saint.

I was raised by librarians, one of whom was a book preservation specialist. Some might think that this would give me a reverence for the codex book, but it totally doesn’t, because I know how incredibly fragile they are—and also how much space they take up. And the importance of libraries isn’t that they hold books, it’s that they hold information and knowledge, regardless of what form it takes.

And as a writer? I could give a damn what the medium by which the words I write are delivered. What matters to me is that they’re delivered. There’s nothing especially holy or unique about a codex book. I mean, don’t get me wrong, it’s awesome, but it’s not the be-all and end-all. It was the best way to deliver information in an easy-to-digest form for a long time, and it’s still a pretty damn good one. But the important thing is the words, not the delivery method.

Cogley’s argument that you can’t get the same feel for the law when you get it out of a computer that you can out of a book is utter, total, and complete nonsense, especially given that he cites works like the Magna Carta, the U.S. Constitution, the Code of Hammurabi—none of which were written in codex books. Such a format is just as bastardized a form of the Magna Carta as a computer would be, by Cogley’s argument.

Speaking of nonsense, that’s also how I’d categorize Cogley’s argument that Kirk has a right to face his “accuser,” the ship’s computer. A computer is a tool. Does someone on trial for murder today have the same right to confront the machine that did the DNA test that confirmed that his hand held the weapon that was used in the deed? Does someone on trial for assault have the right to confront the video camera that recorded the fight in question? Of course not—a computer, a DNA analyzer, a video camera, they’re all tools, not witnesses.

I’m also wondering what Cogley’s plan was. The defense rested before Spock ran in with his story about beating the computer at chess, which meant he was finished defending Kirk. The impassioned speech about humanity dying in the shadow of the machine came after he’d already given up. He was just gonna throw Kirk to the wolves, until Spock gave him the opportunity to pull a stupid rant out of his ass.

Also, holy crap, was that an absurdly Rube Goldberg-esque plan to isolate Finney on the ship. Yes, let’s just dump everyone off the ship, and then listen for heartbeats, and then use a badly disguised microphone to blot out the heartbeats of everyone on the bridge, and then let’s just get rid of the transporter room—and wait, why didn’t they just do that with the bridge? Or better yet, why didn’t they just, I dunno, use internal sensors or something?

And then a captain who is on trial for murder is allowed to just go off and indulge in a fistfight in the engine room. Why not just use some kind of sedative and pump it into the engine room? (Because then our hero can’t get into a fistfight where his shirt gets ripped.) For that matter, the captain’s lawyer is allowed to leave the ship in the midst of this?

Also, Shaw obviously had a relationship with Kirk—why is she allowed to prosecute him? Especially since she let Cogley get away with his nonsense (though Stone didn’t help by going along with it, too).

The backstory between Kirk and Finney is interesting, as is the use of Jame, and it’s cool to see the procedural elements of the actual court martial, including the acknowledgment of how difficult it is to command a starship and how easy it is to believe that one could go off the deep end. (We’ll see this again in “The Doomsday Machine” and “The Omega Glory,” among other places.) The scene between Stone and Kirk when Stone tries to convince Kirk to accept reassignment and Kirk sticks to his guns and insists on his day in court is an excellent one. But ultimately, this is a spectacularly dunderheaded episode.

Warp factor rating: 4

Next week: “The Menagerie”

Keith R.A. DeCandido usually puts something more interesting here.