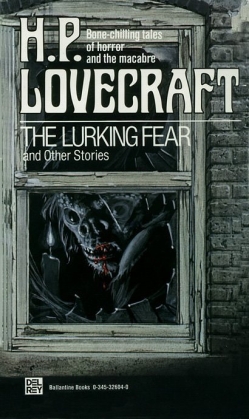

Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories. Today we’re looking at “The Lurking Fear,” written in November 1922 and first published in the January-April 1923 issues of Home Brew. You can read the story here. Spoilers ahead.

Summary: Unnamed narrator of the week seems to be an independently wealthy bachelor with an obsessive taste for the weird. Today he’d have a ghost-hunting reality show. In 1921, he must settle for motoring to the Catskills to investigate a massacre near Tempest Mountain.

A local village has been reduced overnight to “human debris.” Locals connect the slaughter to the ruined Martense mansion which crowns Tempest Mountain. State troopers disregard this theory: not so our narrator. He’ll root out the culprit of the inexplicable attack (one of many over the years), be it supernatural or material. Establishing himself among reporters covering the story from Lefferts Corners, he waits for excitement to ebb so he can launch an unobserved investigation.

Thunder seems to call forth the creeping death. Therefore the narrator and two trusty companions hole up in the mansion on a night threatening storm. The narrator’s no fool—though he’s chosen the room of murdered Jan Martense (possible vengeful ghost) as his center of operations, he’s provided for escape via rope ladders out the window. The hunters rest on an improvised bed by the window, across from a huge Dutch fireplace that keeps drawing the narrator’s eyes. After turning sentinel duty over to companion Tobey, he dozes through troubled dreams. Companion Bennett seems similarly restless, because he throws an arm over the narrator’s chest. Or something does. Agonized screams rouse our guide. Tobey, nearest the fireplace, is gone. Lightning casts a monstrous shadow that can’t be Bennett. When the narrator looks toward the window, where Bennett lay, the man’s gone.

Whose arm lay on the narrator, and why was he, in the middle of the bed, spared?

Shaken but more determined than ever, the narrator befriends reporter Arthur Munroe, who proves both shrewd and sympathetic. They hunt on together, with the locals’ help. One afternoon finds them going over the violated village yet again. The creeping death normally travels under forest cover, so how did it cross the open country between Tempest Mountain and this hamlet? On the night of carnage, lightning caused a landslide on a neighboring hill. A clue? While the pair considers, a thunderstorm drives them into a hovel. Lightning strikes the hill again, and earth rolls. Munroe goes to the window. Whatever he sees fascinates him because he stays there until the storm passes. Unable to call Munroe away, the narrator spins him playfully around—to find the reporter dead, head chewed and gouged, face entirely gone.

The narrator buries Munroe without reporting his death. Is this enough to drive him away from Tempest Mountain? Nope. He now thinks the killer must be a “wolf-fanged” ghost, specifically Jan Martense.

He’s researched the Martense clan. Its founder Gerrit built the mansion in 1670, having left New Amsterdam in disgust at British rule. He refused to leave after finding Tempest Mountain well-named, prone to violent thunderstorms. Trained to shun contact with other colonists, his family became increasingly isolated. Jan Martense escaped to fight with the colonial army, returning in 1760 to a family with whom he shared nothing but the dissimilar eyes (one blue, one brown) that were its hereditary distinction. A friend, receiving no reply to his letters, visited. The animalistic aspect of the Martenses repulsed him; disbelieving their account of Jan’s death by lightning, he dug up the corpse and found the skull crushed by savage blows.

Courts couldn’t find the Martenses guilty of murder, but the countryside did. The family became entirely isolated. By 1816 they seemed to have left the mansion en masse—at least no one alive remained.

Did Jan’s ghost stick around, still blindly enacting vengeance? Knowing his actions are irrational, the narrator digs in Jan’s grave under a lightning-sparked sky. Finally the earth collapses under his feet and he finds himself in a tunnel or burrow. The only irrational thing to do is to squirm through the burrow until his flashlight begins to dim and two eyes glow in the darkness before him. Two eyes and a claw.

Lightning strikes just above, collapsing the tunnel. The narrator digs back to open air, emerging from the cleft side of one of the hummocks that crisscross the mountain and surrounding plain. Huh. Just glacial phenomena?

Later the narrator learns that while he gazed into the weirdly suggestive eyes underground, creeping death attacked twenty miles away! How could the demon be in two places at once?

The narrator can now only explain his persistence by noting that fright can so mix with wonder that it’s relief and delight to throw oneself into the vortex. One night, as he looks toward Tempest Mountain, moonlight shows him what he’s missed. Those hummocks and mounds? They radiate from the cursed mansion like tentacles, or molehills. Frenzied, the narrator digs in the nearest mound and finds—another tunnel! He runs to the mansion and finds in its weedy cellar, at the base of the center chimney, another tunnel entrance!

That’s why he lay in the middle and wasn’t taken! Something from the fireplace grabbed Tobey, something from the window Bennett! There are many demons, none ethereal. Thunder rolls overhead. The narrator hides in a basement corner, and witnesses the emergence of an entire extended family of devil-apes with whitish matted fur, all hideously silent—the others devour a weak one that barely squeals. As they disperse in search of prey, the narrator shoots a straggler. The dying creature’s eyes are dissimilar: one blue, one brown.

The narrator arranges to have the entire top of Tempest Mountain dynamited and all discoverable burrows stopped up. Still he lives in dread of thunder and underground places—and “future possibilities,” for could there not be other Martense clans in the unknown caverns of the world?

What’s Cyclopean: The rage of the lightning bolt that saves the narrator from the underground lurker.

The Degenerate Dutch: This is, in fact, the story with the “degenerate Dutch” living in the Catskills. They are poor mongrels! They whine! They build malodorous shanties!

Mythos Making: Not a particularly Mythos-oriented story—except that every once in a while the narrator randomly goes on about “trans-cosmic gulfs” just in case you forgot this was supposed to be cosmic horror.

Libronomicon: We need to put more stories with unspeakable tomes on the roster.

Madness Takes Its Toll: This narrator may be correct—as many are not—that he’s become a bit unhinged, what with all the cackling and shrieking while digging maniacally in the earth. He’s also a patronizing jerk.

Anne’s commentary

‘Tis an unweeded garden, that grows to seed;

Things rank and gross in nature

Possess it merely.–Hamlet, Act I, Scene 2

Youthful enthusiasm and a case of sympathetic angst led me to commit very much to heart the first three acts of Hamlet. Occasionally this Cyclopean memory-carcass puts forth tendrils of more or less pertinent verbiage. Like recently, when I was walking with “Lurking Fear” in hand. Add to rumination on the overwhelming corruption in this story the sight of wasps swarming on fallen crabapples, and naturally “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark” popped out of my mouth.

That was natural, right?

Anyhow, something is definitely rotten in the Catskills, a picturesque region of New York State more commonly associated with the Hudson River School of landscape painting and the Borscht Belt. Lovecraft hustles us past these delights to the desolate countryside surrounding Tempest Mountain, upon which broods the Martense mansion. Local lore’s always connected the house with a terror that bedevils the area, and for good reason. As Hamlet’s Claudius moans of himself, the Martenses have brought “the primal eldest curse” upon themselves, “a brother’s murder.” The primal brother was Abel; the doomed Martense was Jan, whose comparative normality led his kinsmen to bash in his head.

But what sort of curse have the Martenses courted? Local lore favors a supernatural explanation, that is, Jan Martense’s ghost. Our narrator starts with an open mind. Could be the problem’s supernatural; could be it’s material. As it turns out, the correct answer is behind (should-have-been-left-shut) Door Number Two. Boy, is it ever. It’s telling that the narrator should describe the scene of the first attack as one of “disordered earth” and “human debris” and “organic devastation,” because the material and organic sure show their nastiest faces here.

I’ve mentioned noticing how Lovecraft personifies or gives a certain sentience to the moon, that pale-faced mocker of terrible revelations. Here the moon is the very agent of the reveal as it throws the topography of Tempest Mountain into high relief. However, more pervasively sentient and malign is the diseased landscape itself. As we saw in “Color Out of Space,” Lovecraft often renders vegetation as sinister. “Lurking Fear’s” plants are ”unnaturally large and twisted… thick and feverish.“ Trees are ”wild-armed” and “morbidly overnourished,” with “maniacally thick foliage” and “serpent roots.” Balefully primal, they toss insane branches and leer and hush the wind, which itself is “clawing.” Briers choke the cellar. The long-abandoned gardens feature “white, fungous, foetid, overnourished [again] vegetation that never saw full daylight.” And why shouldn’t the flora be strange and bloated, considering how it sucks “unnamable juices from an earth verminous with cannibal devils”? And we thought cemetery trees were bad.

Animals, so terrifying in “Color,” aren’t found around Tempest Mountain. Either they’re too smart, or the creeping death’s consumed them all. That’s okay. The geography itself is animate—anomalous mounds and hummocks snake across the land, and eventually the narrator realizes that they are “tentacles” centered on the mountain and its crowning ruins.

The Martense curse, then, has sickened everything around their homestead. Murdering Jan didn’t bring ghostly retribution down on them. Instead it set in unstoppable motion the three I’s of decadence already eating away at them. Lovecraft is explicit about two of the I’s: Isolation and inbreeding. These operate with less loathsome results among the local poor. Innsmouth, we initially think, is also plagued by the I’s; Dunwich definitely is. But those Martenses! What a piece of work is man, the paragon of animals yet the quintessence of dust! When he goes down, he goes down hard and becomes “the ultimate product of mammalian degeneration…the embodiment of all the snarling chaos and grinning fear that lurk behind life.”

Actually, he becomes a whitish gorilla, reminiscent of the central horror in “Arthur Jermyn.” Is that really so bad? Yes, Lovecraft answers, because the lurking fear isn’t just the Martense clan, it’s what might lurk now or in the future in other hidden lairs. The lurking fear, the chaos behind life, is genetics, my friends, and mutation and devolution and the final descent of all things organic into entropy. Huh, the crawling chaos of Azathoth at the beginning and a silent creeping death at the end. It is awful that the Martenses have lost the power of human speech. With that goes communication, story-making, humanity itself.

The third I of decadence isn’t mentioned in the text, but it’s powerfully implicit. Shakespeare, doesn’t mind talking about incestuous beds, all “rank sweat” and “stew’d in corruption.” Lovecraft? Not happening, except in the most violently violet of the purple passages for which “Lurking Fear” is notable. That “hypocritical” plain and “festering” mountain! What are they but an enseamed coverlet for “underground nuclei of polypous perversion”? Mounds and hummocks and unnamable juices! Oh my. Impossible to imagine that creatures who’ve gotten over that little taboo surrounding cannibalism won’t have gotten over taboos less mentionable. Lovecraft doesn’t mention incest in this story, though he does choke it out once in “Dunwich Horror,” where more degenerates do deeds of “almost unnamable violence and perversity.”

Lovecraft’s fears about what can happen if you reach too far outward, breeding wise, evolve from “Arthur Jermyn” (bad to mate with apes) through “Dunwich Horror” (really bad to mate with Outer Gods) to “Shadow Over Innsmouth,” (sorta kinda bad to mate with fish-frogs, but on the other hand, could be awesome.) Reaching too far inward, breeding wise? As the Martenses prove, that’s a no-no, period.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Of course, after last week’s discussion of the places where Lovecraft sometimes undermines his own prejudices, we get the source story for The Degenerate Dutch. There are bits I enjoy about this one, but the whole thing is a vicious rant on the supposed dangers of racial degeneration that encompasses everything that’s worst about HP’s oeuvre.

The further I get in this reread, the more I notice how HP’s hatred of other races is nothing compared to his patronizing derision of the rural poor. They are consistently degenerate, timid, superstitious, barely human. At best, they tell strange tales that give some clue that might allow Real Men to take action. Like dynamiting mountains, there’s privilege for you. Of course, I’m sure the locals were grateful for his “protective leadership.”

And of course the gentry have further to fall. Especially those that don’t recognize their own betters: the Martenses, after all, hated English civilization. From there, cannibalism was inevitable.

In spite of the nauseating attitude, there’s something about the sheer hysterical energy and pace of the descriptions that draws one in. There is absolutely no inhibition in the frenzied horde of lugubrious verbiage. Blasphemous abnormalities! Charonian shadows! Charnel shadows! Daemoniac crescendos of ululation! Fungous, fetid vegetation! The language is central here, if you can get past the actual action—it’s manic, uninhibited, boiling and festering and objectively absurd—and I find myself caught up in the rush, even while my inner editor curls gibbering in a corner.

Speaking of curling in a corner, we see here some of the oddities that occur when HP writes a man of action. He’s on record as believing such action to be one of the primary admirable thing about the English race (and lack thereof to be one of the abominably alien things about mine). And yet, he was rather more prone to imagining such things than doing them. So when he tries to write an intrepid adventurer, sometimes the motivation… looks a lot like the motivations driving a nervous horror writer. Here we have a “connoisseur of horrors,” an abomination tourist and ambulance chaser who goes where creepy things have been reported and faffs around “investigating.” He tells you how horrible the whole thing is even while digging maniacally in the earth, but doesn’t seem to care much about the “simple animals” whose massacre drew him in, beyond a distant sympathy. (We won’t even talk about the poor girl to whom one of the monsters “does a deed,” who gets burned to death off-screen alongside it. Why not, Lovecraft didn’t bother.)

So admirable men don’t flee horror, but take action—driven by a sort of obsessive, morbid curiosity rather than any concrete goal. “But that fright was so mixed with wonder and alluring grotesqueness, that it was almost a pleasant sensation.” Lovecraft in a nutshell.

In conclusion, “thunder-crazed” may be my new favorite adjective.

Next week, it might be better not to answer “The Call of Cthulhu.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. Unlike the Martenses, she is extremely fond of thunderstorms.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.