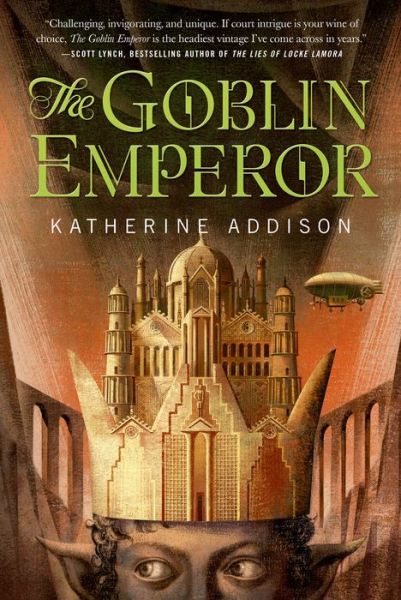

Check out Katherine Addison’s The Goblin Emperor, available April 1st from Tor Books! Preview the first two chapters here, then read chapter three below. You can also read Liz Bourke’s review of the novel here.

The youngest, half-goblin son of the Emperor has lived his entire life in exile, distant from the Imperial Court and the deadly intrigue that suffuses it. But when his father and three sons in line for the throne are killed in an “accident,” he has no choice but to take his place as the only surviving rightful heir.

Entirely unschooled in the art of court politics, he has no friends, no advisors, and the sure knowledge that whoever assassinated his father and brothers could make an attempt on his life at any moment. Surrounded by sycophants eager to curry favor with the naïve new emperor, and overwhelmed by the burdens of his new life, he can trust nobody.

3

The Alcethmeret

The mooring mast of the Untheileneise Court was a jeweled spire in the sunlight. Maia descended the narrow staircase slowly, carefully, aware that the deceptive clearheadedness of fatigue would not extend to coordination, and he would be most unlikely to save himself if he stumbled.

No one knew to await him, and so there was no one at the foot of the mast except the captain, again. Maia was relieved; Chavar caught off balance would be far easier to deal with than Chavar given time to consider and plan.

Maia lengthened his stride past Setheris to catch up to the messenger. “Will you guide us?”

The messenger’s eyes flicked from him to Setheris, and then he bowed. “Serenity. We will be honored.”

“Thank you. And, if you would—” He lowered his voice and dropped formality: “Tell me your name?”

He at least succeeded in startling the messenger out of his stone face for a second: his eyes widened, and then he smiled. “I am Csevet Aisava, and I am entirely at Your Serenity’s service.”

“We thank you,” Maia said, and followed Csevet toward the long roofed walkway that led to the Untheileneise Court itself.

“Court” was a misleading word. The Untheileneise Court was a palace as large as a small city—larger, in fact, than the city of Cetho that surrounded it—housing not merely the emperor, but also the Judiciate, the Corazhas of Witnesses that advised the emperor, the Parliament, and all the secretaries, couriers, servants, functionaries, and soldiers needed to ensure that those bodies did their work efficiently and well. The court had been designed by Edrethelema III and built during the reigns of his son, grandson, and great-grandson, Edrethelema IV through VI. Thus, for a compound of its vast size, it was remarkably and beautifully homogeneous in architecture; rather than sprawling, it seemed to spiral together into the great minareted dome of the Alcethmeret, the emperor’s principal residence.

My home, Maia thought, but the phrase meant nothing.

“Serenity,” said Csevet, pausing before the tall glass doors at the end of the walkway, “where do you wish to go?”

Maia hesitated a moment. His pressing concern was to find and speak to the Lord Chancellor, but he remembered what Setheris had shown him. The emperor hunting all over the court for his chief minister would look ill and ludicrous, and it would grant Chavar the power he was presuming he had. But, on the other hand, Maia knew nothing of the geography of the court, except for the stories his mother had told him when he was small. And since she herself had lived in the Untheileneise Court for less than a year, he could not rely on her tales for any accuracy of information.

Setheris came up to them. Maia thought, Thou hast resources, if thou wilt stretch out thy hand to use them. He said, “Cousin, we require a room where we may have private audience with our father’s Lord Chancellor.”

There was a flicker of something, some unreadable emotion, on Setheris’s face, gone as soon as noticed, and he said, “The Tortoise Room in the Alcethmeret has always been the emperors’ choice for such audiences.”

“Thank you, cousin,” Maia said, and to Csevet, “Take us there, please.”

“Serenity,” Csevet said, bowing, and held open the door for Maia to enter the Untheileneise Court.

The court was not as bewildering as he had expected, and his admiration for Edrethelema III increased. Doubtless behind those beautifully paneled walls there were warrens and webs, but the public corridors of the court were straight and broad and clearly designed for an emperor to be able to find his way about his own seat of government. The distances were fatiguing, but about that Maia imagined Edrethelema had been able to do little; the simple fact of the palace’s necessary size precluded convenience.

They were seen—as how could they not be?—and he was able, with bitter amusement, to distinguish those who were in the Lord Chancellor’s confidence and those who were not, for only those who recognized Csevet and had known his mission looked alarmed. No one recognized the new emperor on his own merits. In sooth, I look not like my father, and I am pleased at it, Maia thought defiantly, although he knew that the dark hair and skin he had inherited from his goblin mother would do him no favors in the Untheileneise Court. And, even more grimly: They will learn to know me soon enough.

Csevet opened another elaborately wrought door, this one a wicket set in a massive bronze gate, and passing through, Maia found himself standing at the base of the Alcethmeret. Staircases wound in wide spirals around the inside of the tower; the lower levels were disturbingly open, a reminder from one emperor to the next that a private life was something he would not have. But about halfway up the tower’s height, the architecture changed, a boundary marked by a pair of floor-to-ceiling iron grilles; those were open now, for there was no emperor in residence, and Maia could see that beyond them the staircase was enclosed and guessed that the rooms would likewise be smaller, more customary. Less exposed.

There were servants everywhere, it seemed; for a moment he could not even sort them out, as they turned and stared and dropped to their knees. Some of them prostrated themselves full-length as Csevet had done, and in that excess of formality, he read their fear. Belatedly, he realized that catching Chavar off guard also meant catching the servants of his household in unreadiness, an unkindness they had done nothing to deserve. Setheris would tell him it was sentimental nonsense to care for the feelings of servants, but in Barizhan servants were family—legally always and often by blood. The Empress Chenelo had raised her child by that principle, and he had clung to it all the harder because of Setheris’s opposition.

Csevet said, “The Tortoise Room, Serenity?”

“Yes. And then,” arresting Csevet as he turned to lead the way up the nearer staircase, “we would speak with our household steward. And then the Lord Chancellor.”

“Yes, Serenity,” Csevet said.

The Tortoise Room was the first room beyond the iron grilles. It was small, hospitable, appointed in amber-colored silk that was warm without being oppressive. The fires had not yet been lit, but Maia had barely seated himself in the chair by the fireplace when a girl scurried in, her hands shaking so badly she almost dropped the tinderbox before she could get the fire to light.

When she had left—her head lowered so far that, first to last, the only impression Maia gained of her was of her close-cropped, goblinblack hair—Setheris said, “Well, boy?”

Maia tilted his head back to regard his cousin where he leaned, not quite lounging, against the wall. “Do not presume, cousin, when thou hast warned me of presumption so cannily.”

A great many things were at that moment made worthwhile, as he watched Setheris gape and splutter like a landed fish. Remember, he said to himself, a poisonous pleasure.

“I raised thee!” Setheris said, all injury and indignation.

“So you did.”

Setheris blinked and then slowly went to his knees. “Serenity,” he said.

“Thank you, cousin,” Maia said, knowing full well that Setheris offered him only the form of respect, that even now, as at Maia’s wave he took the other chair, he was incensed with Maia’s arrogance, waiting for the correct moment to reassert his control.

Thou wilt not, Maia thought. If I achieve nothing else in all my reign, thou wilt not rule me.

And then Csevet said from the door, “Your house steward, Serenity. Echelo Esaran.”

“We thank you,” Maia said. “The Lord Chancellor, please.”

“Serenity,” Csevet said, and vanished again.

Esaran was a woman in her mid-forties. The sharp, austere bones

of her face were suited by a servant’s crop, and she wore her livery with an air that would have done justice to an empress’s coronation robes. She went to her knees gracefully; her face and ears revealed nothing of her thoughts.

“We apologize for our sudden arrival,” Maia said.

“Serenity,” she said, the word stiff and precise, unyielding, and he realized, his heart sinking, that here was one who had served his father with her heart as well as her mind.

I do not want more enemies! he cried out, but only in his own thoughts. Aloud, he said, “We do not wish to disrupt your work any more than we must. Please convey to the household staff our gratitude and our… our sympathy.” He could not say he shared their grief when he did not—and when this cold-eyed woman knew he did not.

“Serenity,” she said again. “Will that be all?”

“Yes, thank you, Esaran.” She rose and departed. Maia pinched the bridge of his nose, reminding himself that, although the first, she would hardly be the last inhabitant of the Untheileneise Court who would hate him for his father’s sake. And, moreover, it was foolish and weak to feel hurt at her enmity. Another luxury thou canst not afford, he thought, and did not meet Setheris’s eyes.

It took some time for Csevet to return with the Lord Chancellor. Maia had been trained, first by his mother, then by Setheris, to disregard boredom, and he had no lack of matters to consider. He kept his back straight, his hands relaxed, his face impassive, his ears neutral, and thought about all the things he did not know, had never been taught because no one had imagined an emperor with three healthy sons and a grandson would ever be succeeded to the throne by his fourth and ill-regarded son.

I shall need a teacher, Maia thought, and Setheris is not my choice.

If there was a contest waged in the Tortoise Room, it was Setheris who lost it. He broke the silence: “Serenity?”

“Cousin?”

He saw Setheris’s throat work and his ears dip, and his attention sharpened. Anything that discomfited Setheris was reflexively a matter of interest. “We… we would like to speak to our wife.”

“Of course,” Maia said. “You are welcome to send Csevet in search of her when he returns.”

“Serenity,” Setheris said, not meeting Maia’s eyes but continuing stubbornly on. “We had hoped to… to introduce her to your favor.” Maia considered. He knew little of Setheris’s wife, Hesero Nelaran,

save that she had worked tirelessly and fruitlessly to get Setheris recalled to the Untheileneise Court and had sent him weekly letters with all the gossip and intrigue she could gather. Maia had assumed—in part because Setheris never spoke of her save, when in a particularly good humor, to relay choice tidbits of scandal over the breakfast table—that theirs was an arranged marriage, as loveless, if not as hate-filled, as his mother’s marriage to the emperor. But Setheris’s obvious distress argued otherwise.

Do not make enemies where it needs not, he thought, remembering Merrem Esaran’s enmity, considering the likely course of his upcoming interview with the Lord Chancellor. He said, “We would be pleased. After we have spoken to the Lord Chancellor.”

“Serenity,” Setheris said, acquiescing, and they fell again into silence.

Maia noted when an hour had passed, and wondered if it was that the Lord Chancellor was unusually well hidden—most odd and unadmirable in a man planning a state funeral—or that he was trying to regain the whip hand by a calculated show of disrespect.

He harms none but himself by such tactics, Maia thought. He cannot delay long enough to force me into step with his plans—at least not without risking dismissal on grounds of contempt. Perchance he thinks I would not do it, but he will not rule me, either. And if he has no loyalty to me, it is just as much the case that I have no loyalty to him. I do not even know the man’s face.

Immersed in these grim thoughts, it took him a moment to realize that the approaching tumult on the stairs had to be Chavar. “Has he brought an army with him?” Setheris murmured, and Maia repressed a smile.

Csevet, looking a little winded, appeared in the doorway. “The Lord Chancellor, Serenity.”

“We thank you,” Maia said, and awaited the entrance of Uleris Chavar.

Without realizing it, Maia had been expecting a copy of his father’s state portrait: tall and cold and remote. Chavar proved to be none of these things. He was short and stocky by elven standards, choleric, and he was almost on top of Maia before he bothered to bend a knee.

“Serenity,” he said with perfunctory courtesy; Maia had to resist the urge to stand up, to prevent Chavar from looming over him. Instead, he jerked his head at Setheris—tacit permission to send Csevet in search of Osmerrem Nelaran—and, as Setheris crossed eagerly to where Csevet stood, Maia waved Chavar to the empty chair, a sign of favor the Lord Chancellor could not ignore.

Chavar sat down with ill grace and said, “What is Your Serenity’s will?”

It was a formula, brusquely uttered; he already had his mouth half-open—doubtless to explain the arrangements he had made for the funeral—when Maia said, as gently as he could, “We wish to discuss our coronation.”

Chavar’s mouth remained half-open for a moment. He shut it with a click, inhaled deeply, and said, “Your Serenity, surely this is not the time. Your father’s funeral—”

“We wish,” Maia said, less gently, “to discuss our coronation. When that is arranged to our satisfaction, we will hear you upon the subject of our father’s funeral.” He caught and held Chavar’s gaze, waiting.

Chavar did not look away. “Yes, Serenity,” he said, and the hostility was in the air between them like a half-drawn sword. “What are your plans, if we may be so bold?”

Maia saw the trap and skirted it. “How quickly can you arrange our coronation? We do not wish any more delay than is necessary in rendering the proper rites and obsequies to our father and brothers, but we also do not wish to do anything in a slipshod or hasty fashion.”

Chavar’s expression was, if only for a moment, distinctly pained. It was clear he had not expected an eighteen-year-old emperor, raised in virtual isolation, to provide him with any contest at all. Sometime, Chavar, Maia thought, you must try living for ten years with a man who hates you and whom you hate, and see what it does to sharpen your wits.

Something of this thought must have shown in his eyes, for Chavar said quite promptly, “We can prepare the coronation ceremony for tomorrow afternoon, Your Serenity. It will mean delaying the funeral for another day.…” He trailed off, clearly hoping that Maia might still be browbeaten into acceding to his Lord Chancellor’s wishes.

But Maia was considering something else. Setheris had been trained as a barrister, before he fell afoul of Varenechibel’s temper, and he had passed as much of that training on to Maia as he felt it likely a teenage boy—of whose intelligence he had no great opinion—would comprehend. There had been no kindness in the gesture, merely Setheris’s rigid sense of what befitted the son of an emperor, and it did not befit the son of an emperor to reach manhood entirely ignorant. And, Maia supposed, it had been something to do, a commodity that Setheris must surely have needed as desperately as he did himself.

But again there was reason for gratitude, although still he felt none. For at least Setheris had taught him, among other things, the forms and protocols surrounding a coronation. He said, “Will that give the princes time to make the journey?” He knew perfectly well it would not—else Chavar would have scheduled the funeral for that time— but he was not yet prepared to accuse the Lord Chancellor of open contempt. It would be a rare start to my reign, he thought, but kept the bitter quirk off his face. He would have to work with Chavar until such time as he was sufficiently familiar with the court to choose his own Lord Chancellor, and he feared that time might be far distant.

And Chavar did a passable job of pretending chagrin. “Serenity, we most humbly beg your pardon for our oversight. The princes, if we send messengers today, cannot arrive before the twenty-third.”

As we know from your letter, Maia did not say, and he saw acknowledgment of that in Chavar’s eyes. The Lord Chancellor said, “Serenity. We will put preparations in train for your coronation at midnight of the twenty-fourth.” It was an offer of truce, no matter how obliquely or grudgingly offered, and Maia accepted it as such.

“We thank you,” he said, and gestured Chavar to his feet. “And the funeral on the twenty-fifth? Or can preparations be made for the twenty-fourth?”

“Serenity,” Chavar said with a half bow. “The twenty-fourth is achievable.”

“Then let it be so.” Chavar was almost at the door when Maia remembered something else: “What of the other victims?”

“Serenity?”

“The others on board the Wisdom of Choharo. What arrangements are being made on their behalf?”

“The emperor’s nohecharei will of course be buried with him.”

Chavar was not being deliberately obstructive, Maia saw; he genuinely didn’t understand.

“And the pilot? The others?”

“Crew and servants, Serenity,” Chavar said, baffled. “There will be a funeral this afternoon at the Ulimeire.”

“We will attend.”

That had both Setheris and Chavar staring at him. “They are as much dead as our father,” Maia said. “We will attend.”

“Serenity,” Chavar said with another hasty bow, and left. Maia wondered if he was beginning to suspect his new emperor of insanity.

Setheris, of course, had no doubts; he had aired his views on the perniciousness of Chenelo’s influence more than once. But he forbore to speak, merely rolling his eyes.

Csevet had not yet returned, and Maia had a use for this breathing space. “Cousin,” he said, “would you have our father’s Master of Wardrobe sent to us?”

“Serenity,” Setheris said with a bow as perfunctory as Chavar’s, and went out. Maia took the opportunity to stand, to try to ease the harp-string tension of his muscles. “Not all hands will be against thee,” he whispered to himself, but he feared it for a lie. He rested his elbows on the mantel, his head in his hands, and tried to conjure in his mind the sunrise seen from the Radiance of Cairado, but it was blurred and dull, as if seen through a pane of dirty glass.

There was a hesitant tap at the door, an even more hesitant voice saying, “Ser… Serenity?”

Maia turned. A middle-aged man, tall and stooped, with the mild, nervous expression of a rabbit. “You are our Master of Wardrobe?”

“Serenity,” the man said, bowing deeply. “We… we so served your late father, and so will serve you, an it be your pleasure.”

“Your name?”

“Clemis Atterezh, Serenity.” Maia saw nothing but anxiety to please in his face or stance, heard nothing but diffidence and nerves in his voice.

“We will be crowned at midnight on the twenty-fourth,” he said. “Our father and brothers’ funeral will be that day. But today there is the funeral for the other victims, which we wish to attend.”

“Serenity,” Atterezh said politely, uncomprehending.

“What does an uncrowned emperor wear to a public funeral?”

“Oh!” Atterezh advanced slightly into the room. “You cannot wear full imperial white, and court mourning is inappropriate… and you certainly can’t wear that.”

At the cost of a savagely bitten lip, Maia did not giggle. Atterezh said, “We will see what can be done, Serenity. Do you know when the funeral is to be held?”

“No,” Maia said, and cursed himself for his stupidity.

“We will ascertain,” Atterezh said. “And when it is convenient to Your Serenity, we are at your disposal to discuss your new wardrobe.”

“Thank you,” Maia said. Atterezh bowed and departed. Maia sat down again in bemused wonderment. He had hardly ever had a piece of new clothing before, much less an entire new wardrobe. Thou’rt emperor now, not a half-witted ragpicker’s child, he said to himself, and felt almost dizzy at the reminder of his own thought from not even twelve hours ago.

A clatter of feet on the stairs. Maia looked up, expecting Setheris, but it was a breathless, frightened-looking child of no more than fourteen, dressed in full court mourning and clutching a black-bordered and elaborately sealed letter.

“Your Imperial Serenity!” the boy gasped, throwing himself fulllength on the floor.

Maia had even less idea what to do with the gesture now than he had in the receiving room at Edonomee. At least Csevet had had the grace to get himself back on his feet again. A little desperately, he said, “Please, stand.”

The boy did, and then stood goggling, his ears flat against his skull. It couldn’t be the effect of being this close to an emperor—the boy wore the Drazhadeise crest and thus was in the service of the emperor’s household. Maia knew what Setheris would say: Cat got your tongue, boy? He could even hear it, somewhere in the back of his head, and what it would sound like in his own voice. He said patiently, “You have a message for us?”

“Here. Serenity.” The boy shoved the paper at him.

Maia took it, and to his own horror heard himself say, “How long have you served in the Untheileneise Court?” He barely managed to bite the “boy” off the end of it.

“F-four years. Serenity.”

Maia raised his eyebrows, mirroring the cruel incredulity he had so often seen on Setheris’s face; he waited a single beat and saw the boy’s face flood red. Then he turned his attention to the letter, as if the boy held no more interest for him. It was addressed, in a clear clerk’s hand, to the Archduke Maia Drazhar, a presagement that did not make him any happier.

He broke the seal and then, realizing the boy was still there, raised his head.

“Serenity,” the boy said. “I… we… she wants an answer.”

“Does she?” Maia said. He looked pointedly past the boy at the door. “You may wait outside.”

“Yes, Serenity,” the boy said in a half-choked mumble, and slunk out like a whipped dog.

Setheris would be proud, Maia thought bitterly and opened the letter. It was, at least, short:

To the Archduke Maia Drazhar, heir to the imperial throne of Ethuveraz, greetings.

We have need to speak to you regarding the wishes of your late father, our husband, Varenechibel IV. Although we are in deepest mourning, we will receive you this afternoon at two o’clock.

With wishes for familial harmony,

Csoru Drazharan, Ethuverazhid Zhasan

I do not doubt that she wants an answer, Maia thought. The widow empress lacked even the subtlety of the Lord Chancellor. He wondered with an unhappy shiver what Varenechibel had told his fifth wife about her predecessor and her predecessor’s child.

The Tortoise Room had a small secretary’s desk tucked into the corner behind the door, and no matter the widow empress’s rudeness, he owed her a reply in his own hand. Or perhaps more accurately, considering the clerk’s hand of her letter, he owed himself a reply in his own hand. He found paper, dip pen, ink, wax—no seal, and he supposed the assumption was that anyone writing a letter would have his own signet. Maia did not; it was one of the many tokens of adulthood he had not received on his sixteenth birthday. A thumbprint would do for now, though it would probably get him accused of following his mother’s barbaric customs. So be it, he thought, dipped his pen in the ink, and wrote:

To Csoru Drazharan, Ethuverazhid Zhasanai, greetings and great sympathy.

We regret that a prior obligation prevents us from speaking with you this afternoon as you request. We shall, however, be pleased to grant you an audience tomorrow morning at ten; we are eager to hear anything you can tell us of our late father.

Until our coronation, we are using the Tortoise Room as a receiving room.

With respectful good wishes,

And here Maia paused. To sign with his given name would be to acknowledge that she had been correct in addressing him in that fashion. But he had not, until that moment, given any thought to the choosing of a dynastic name, and it was hard to get beyond his first, instinctive reaction: I will not be Varenechibel V.

No one forces thee, he thought as the ink dried patiently on his pen. An thou did choose Varenechibel, the court would doubtless construe it an insult.

He knew from Setheris’s impatient tutelage that his great-greatgreat-grandfather, Varenechibel I, had chosen to signal his rejection of the policies of his father, Edrevechelar XVI, by refusing the imperial prefix that every emperor since Edrevenivar the Conqueror had used, choosing to become Varenechibel the first of that name instead of the ninth Edrenechibel. His son and grandson had followed his lead, being Varenechibel II and III. His great-grandson (willful, though never particularly imaginative, Setheris had said dryly) had defied burgeoning tradition by becoming Varevesena. And then had come Varenechibel IV.

And now Maia.

The emperors of what was informally called the Varedeise dynasty—as if their chosen prefix were a surname—were noted for their isolationist policies, their favoring of the wealthy eastern landowners, and their apparent inability to see anything wrong with bribery, nepotism, and corruption. Setheris had gone into scathing detail about the Black Mud Scandal of Varenechibel III’s reign (so called because it stained everyone who came in contact with it), and Varevesena’s disgraceful habit of giving munificent but otherwise empty political appointments to his friends’ newborn children. “At least he is not personally corrupt,” Setheris had said grudgingly of Varenechibel IV, but Maia thought that very cold praise.

He did not want to continue any of the Varedeise traditions; embracing their traditional hostility to Barizhan seemed self-destructive in a way that he found uncomfortably ambiguous between the symbolic and the literal. Even if he had wanted to, the encounter with Chavar demonstrated that he would have a grimly difficult battle winning the trust of his father’s ardent supporters.

Better to build new bridges, he thought, than to pine after what’s been washed away. He dipped his pen again and wrote with pointed legibility across the bottom of the page, Edrehasivar VII Drazhar. Edrehasivar VI had had a long, peaceful, and prosperous reign some five hundred years ago.

Let it be an omen, Maia thought, a quick prayer to Cstheio, the dreaming lady of the stars, and folded and sealed the letter. He had a lowering feeling that he was going to need all the omens of peace he could accumulate.

The boy was lingering nervously on the landing. “Here,” said Maia. “Take this to the zhasanai with our compliments.”

Wide-eyed, the boy took the letter. He had caught the nuance— “zhasanai,” not “zhasan”—and Maia did not doubt that the widow empress would be told. She could style herself a ruling empress all she liked, but she was not one. She was zhasanai, an emperor’s widow, and had best remember that she was dependent now upon her unknown stepson’s goodwill.

“Serenity,” the boy said, bowed, and fled.

Already I become a tyrant, Maia thought, and retreated again into the Tortoise Room to wait for Setheris and his wife.

But Setheris did not reappear until after Atterezh had come back bearing a mass of black and plum-colored cloth embroidered in white: mourning colors without the strict formality of court mourning. He also brought the information that the funeral would be held at three o’clock—as sundown was the most correct hour for funerals, it was also the most expensive, so that the families had had to pool their money to get as close as they could—and added that he had advised Esaran of the emperor’s intention and obtained her assurance that the emperor’s carriage would be ready at half past two. Maia could have wept with gratitude at finding one person who did not resist or resent him, but such an action was unbecoming to an emperor and would frighten and perplex Atterezh very much.

Thus, he stood and allowed Atterezh to take measurements, to drape and fuss with the cloth, and it was in the midst of this, as Atterezh mumbled arcanely to himself, that Setheris appeared in the doorway and demanded, “Has Uleris not sent you a guard?”

“No,” Maia said.

“Who is this?”

“Our Master of Wardrobe.”

“Then he hasn’t sent a maza, either.”

“No. Cousin, what—?”

“We will see to it,” Setheris said. “And we would advise you to replace your Lord Chancellor as soon as you may. Uleris seems to be growing forgetful in his old age.”

Since Setheris and Chavar were of an age, the insult was a pointed one—enough so that Maia realized this was not mere officiousness on Setheris’s part, nor angling for Chavar’s position. “Cousin, explain.”

“Serenity,” Setheris said, reminded by the imperative. “The Emperor of the Elflands has both the right and the obligation to be attended at all times by the nohecharei, the guardian of the body and the guardian of the spirit. And especially if you intend to persist in this lunatic idea…” He waved a hand at the cloth draped over Maia’s shoulder.

“We do,” Maia said. “We are sure the Lord Chancellor has much on his mind. If you would see to the matter, we would be grateful, and when you return, we will be pleased to receive your wife.”

“Serenity,” Setheris said, bowed, left.

Maia knew—everyone knew—about the emperor’s nohecharei, the guardians sworn to die before they would allow harm to come to him: one, the soldier, to guard with his body and the strength of his arm; the other, the maza, to guard with his spirit and the strength of his mind. Edonomee’s cook could sometimes be coaxed into telling stories, so Maia even knew about Hanevis Athmaza, nohecharis to Beltanthiar III, who had entered a duel of magic with Orava the Usurper, the only magic-user ever to attempt to take the throne. Hanevis Athmaza had known Orava would kill him, but he had held the usurper off the emperor until the Adremaza, the master of the mazei of the Elflands, had reached them. Orava had been defeated, and Hanevis Athmaza, horribly injured, had died in his emperor’s arms. In his early adolescence, Maia had dreamed of becoming a maza, of becoming perhaps his father’s nohecharis and earning his love, but he had shown no more aptitude for magic than he showed (Setheris said) for anything else, and that dream, too, had died.

He had never dreamed of becoming emperor.

Atterezh continued with his task, the only sign that he had even noticed the conversation being that his discussion with himself was now inaudible rather than merely under his breath. Maia hoped his father had chosen his household staff for their discretion, for there was no part of that exchange with Setheris that he wished bruited about the court. But to say so would offend Atterezh and shatter the precarious fictions by which servants and nobles protected each other.

“Serenity,” said Atterezh, climbing slowly to his feet. “I will have clothes in readiness for you at two o’clock, if that will please?”

“Yes. We thank you, Atterezh.”

Atterezh bowed, released Maia from his draperies, and departed. Maia observed gloomily that thus far the life of an emperor seemed chiefly to involve sitting in a small room and watching other people come and go.

That’s more variety than thou hadst at Edonomee, where there was no one either to come or to go, he thought, and managed a smile at his own foolish self-pity.

He sat down wearily, wondering if there might be time for a nap before he had to dress for the funeral. The clock gave the time as quarter of ten (which seemed either too late or too early, although he could not tell which). Esaran would not love him better if he demanded a bed made ready at ten in the morning.

He rubbed his eyes to keep them from drifting shut, and here was Setheris again, bristling with energy and spite. “Serenity, we have spoken with the Captain of the Untheileneise Guard and the Adremaza, and they will see to the matter. They wished us to convey to you their apologies and contrition. No slight was meant, for they were expecting the Lord Chancellor to inform them of your arrival.”

“Do you believe them?”

“Serenity,” Setheris said, acknowledging the justice of the question. He considered a moment, his head tilted to one side, his eyes as bright as a raptor’s. “We are inclined to believe they speak in good faith. They are men with many other concerns, and we, too, expected Chavar to inform them.”

“Thank you, cousin,” Maia said; although those words were grimed with years of sullen irony, he said them as lightly, as gently, as he could. “And your wife?”

“Serenity,” Setheris said, bowing.

He turned and beckoned. Maia heard the click of shoe heels and rose to his feet. Hesero Nelaran stopped in the doorway to drop a deep and magnificent curtsy, the old-style honor that the Empress Csoru had made unfashionable. “Your Serenity,” she said, her voice as smooth as Setheris’s was sharp.

She was a year or two younger than her husband, crow’s-feet showing behind her maquillage. Her clothes were the black of proper court mourning: a floor-length dress trailing a train like a snake’s tail; a quilted and elaborately embroidered jacket, plum on black, frogged with garnet clasps like drops of blood. Her hair was dressed with black lacquer combs and tashin sticks and strands of faceted onyx. She was not beautiful, but through sheer force of elegance she contrived to seem so.

Since his mother’s death, Maia’s personal acquaintance with women had been limited to Edonomee’s stout cook and her two skinny daughters who did the housework. Although he had studied the fashion engravings in the newspapers with great care, there had been nothing that could have prepared him for Hesero Nelaran; he felt his composure shatter and fall to the floor about his feet.

“Osmerrem Nelaran,” he managed finally, stumbling over his words like any callow youth, “we are very pleased to make your acquaintance.”

“And we are pleased to make yours. We are also more grateful than we can say that you have allowed our husband to return to the Untheileneise Court.” She sank again, this time not merely into a curtsy, but into a full-length prostration every bit as graceful as Csevet’s. “Serenity, our honor and our loyalty are yours.”

He said inadequately as she rose to her feet again, “We thank you, Osmerrem Nelaran.”

“May we not count ourself your cousin, Serenity?”

“Cousin Hesero,” he amended.

She smiled at him, and he melted in the warmth of it, barely able to keep his wits together sufficiently to realize that she was speaking, asking about his coronation. “Midnight on the twenty-fourth,” he said, and she nodded with grave approbation, as if she had been worried that he might choose some other, less suitable time.

“Serenity,” Setheris said, “you must not allow us to impose on you.”

“We have much to do,” Maia said to Hesero, partly out of habitual obedience to Setheris’s obliquely worded commands, partly because he did not think he could sustain the audience much longer without making an utter driveling fool out of himself. “But we will hope for an opportunity to speak to you again.”

“Serenity,” they said. Hesero curtsied again; Setheris made a stiff, jerky little bow like a clockwork toy. She swept out with the same grace with which she had entered; she had one thin milk-white braid falling down her back past her hips, following the line of her spine. Setheris hurried after her, and Maia sank back into his chair, now abruptly breathless as well as fatigued.

Thou hast no head for dalliance, he said to himself, and began to laugh. He tried to stop, but it was beyond his power; the laughter seized and shook him like a terrier with a rat. The best he could do was to keep his vocal cords silent, suffering the paroxysm with no more noise than the occasional gasp for breath. It was as painful as choking or the terrible rattling cough of the bronchine, and when at last it released him, he had to wipe tears off his face.

And then he looked up, straight into the eyes of a sober-faced young man dressed as a soldier and with a soldier’s topknot, but wearing the Drazhadeise seal on a baldric across his chest. “Serenity,” he said, and knelt. His disapproval was palpable.

Maia wondered in horror how long he had been standing there, waiting for his emperor to be in a fit state to receive him. “Please rise. You are one of our nohecharei?”

“Yes, Serenity,” the young man said, standing straight again. “We are Deret Beshelar, Lieutenant of the Untheileneise Guard. Our captain has ordered us to serve as a nohecharis—unless Your Serenity is not pleased to accept our service.”

Maia wished he could say, No, we are not pleased, and be rid of this disapproving wooden soldier. But he could not offend the Captain of the Untheileneise Guard without giving a reason, and what reason could he give? He caught me laughing the day after my father’s death. He could not say that, and he read in Lieutenant Beshelar’s vast disapproval an equally vast probity, and that, he felt, he would need more than the man’s friendship.

“We see no reason to be displeased with the captain’s choice,” he said, and Beshelar said, “Serenity,” in such a flat, withering voice that Maia knew he had heard the phrase as an attempt at flattery.

Before he could decide whether he could say anything to ameliorate the wrong-footedness of the conversation, or whether he would merely dig himself in deeper with the attempt, another voice said, “Oh, damn. We did so hope we would get here first. Serenity.”

Maia blinked at this second young man, now kneeling in the doorway. He, too, wore a baldric with the Drazhadeise seal, but it looked almost incongruous over his shabby blue robe. As he stood again, unfolding a remarkable length of bony leg, Maia saw that he was taller than Beshelar, as gawky as a newborn colt. The pale blue eyes behind their thick round-lensed spectacles were myopic, gentle, and the one beauty in a face dominated by a long, higharched nose. His untidy maza’s queue did nothing to flatter him, but he was clearly not the sort of man who would ever care. He said, “We are Cala Athmaza. The Adremaza sent us.”

Beshelar let out a slight pained noise, not quite a sigh and not quite a snort. But the maza seemed to find nothing insufficient in his introduction, merely stood blinking benevolently at Maia, and Maia found nothing insufficient in his introduction, either.

“We are pleased,” he said. And to both of them, “We are Edrehasivar, to be crowned the seventh of that name at midnight of the twenty-fourth.”

“Serenity,” they said together, bowing, and then Cala said, “Serenity, there is a young man on the landing who looks as if he does not know whether he ought to stay or leave.”

“Show him in,” Maia said, and Cala and Beshelar stood aside.

Appearing between them, Csevet said, “We beg your pardon, Serenity. We did not know if you required our services for anything else.”

Maia hid a wince. He had forgotten about Csevet, which was thoughtless and arrogant. “Have you other duties?”

“Serenity,” Csevet said, bowing. “The Lord Chancellor has been so good as to intimate that he will second us to your service, if it would be pleasing to you.”

“That is very kind of the Lord Chancellor,” Maia said, meeting Csevet’s eyes in a moment of shared, pained amusement. “Then we would be very grateful if you could…” He gestured for a word that was not there. “If you could organize our household?”

He heard the plaintive note in his own voice, but Csevet disregarded it. “It shall be as Your Serenity wishes,” he said, bowing more deeply. “We will begin with…” He consulted his pocket watch. “Luncheon.”

The Goblin Emperor © Katherine Addison, 2014