Mystery Science Theater 3000 was a classic cult show, taking B-movies, sci-fi clichés, and pop culture references and blending them all into a consistently hilarious masterpiece that also ended up providing a sort of stealth manual for life. In the not too distant past, it gave me a way to me a way to look at life and writing that made the whole growing-up-and-trying-to-be-a-real-writer-thing much less frightening.

I had a joke I used to tell my friends, that I was basically a feral child, and that I was only civilized through my fortunate exposure to PBS. Sesame Street and LeVar Burton gave me just enough social skills to make it to high school. Then I discovered this man:

I tend to assume that everyone knows this show, but in reading the intriguing Onion AV Club discussion about the changes in MST3K’s structure, I saw that even some AV Club staffers were unfamiliar. So, a quick refresher: Joel (or Mike) and the companion robots Crow T. Robot and Tom Servo watch terrible movies while Mad Scientists monitor their minds, and Mike (or Joel) and the ’bots make fun of said movies in order to stay sane. This format allows Joike and the ’bots to run amok through 40 years of pop culture, time, space, and occasionally the American Midwest, making fun of everything. That’s really all you need to know, and leads us into lesson one:

1. Life is a choice between having control of when the movie begins and ends, and having robot friends.

Finding himself on the ship, Joel has to make the choice between controlling “when the movie begins and ends” and using those unnamed, but apparently “special,” parts to make his robot friends. Granted, this is one line in a song packed with information, but it tells us everything we need to know about Joel’s character. Trapped in a seemingly hopeless situation, Joel creates companionship for himself rather than trying to establish any dominance over his environment—which I think would be the most natural impulse. You’re stuck in space, and Mad Scientists are giggling at you through a viewscreen—of course you’d want to carve out any space you could to establish personal boundaries. But not Joel. He even gave his robots pals free will (which he notably regrets in Experiment 314: Mighty Jack.) That’s just cool.

Finding himself on the ship, Joel has to make the choice between controlling “when the movie begins and ends” and using those unnamed, but apparently “special,” parts to make his robot friends. Granted, this is one line in a song packed with information, but it tells us everything we need to know about Joel’s character. Trapped in a seemingly hopeless situation, Joel creates companionship for himself rather than trying to establish any dominance over his environment—which I think would be the most natural impulse. You’re stuck in space, and Mad Scientists are giggling at you through a viewscreen—of course you’d want to carve out any space you could to establish personal boundaries. But not Joel. He even gave his robots pals free will (which he notably regrets in Experiment 314: Mighty Jack.) That’s just cool.

2. Always do your research!

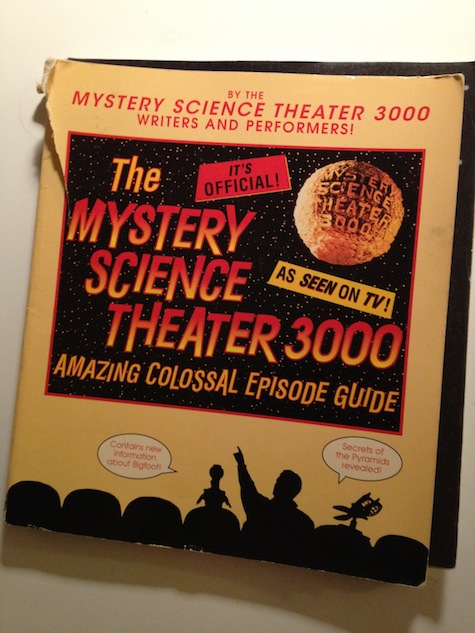

When I was in high school, and got my hands on a copy of the Amazing Colossal Episode Guide, I read it repeatedly.

(Seriously – the black isn’t some border effect, it’s the guts of the book falling out.)

In the entry on Experiment 202: The Sidehackers, Mike Nelson talks about how, up to that point, the writers would watch portions of movies they thought might work for the show, schedule writing sessions, and then sit down as a group to go through an initial riff. This tactic worked until this movie, when they discovered that a brutal rape and murder scene happens toward the end, and is actually a catalyst for the ending. They had to cut a pivotal scene, and try to write jokes around the gap this created in an already thin plot. Plus, obviously, the idea of writing jokes about a film that ended so tragically wasn’t a pleasant experience. They changed their policy based on this movie, and screened complete movies from then on before choosing.

3. Specificity = universality.

The more local the riffs got, the better they were. Circle Pines, Minnesota accents, casserole recipes, Garrison Keillor digs, the Wisconsin Dells, Packers, Prince…for a girl trapped in flat, dull, sub-tropical, tourist-trap Florida, these tiny glimpses of life in the Northern Midwest were like windows opening into a wider, less-humid world. It also gave me personal investment in the world of the show that I wouldn’t have had otherwise, which leads to the idea that despite the silliness of the show, and the advice not to take it too seriously, these characters had more depth than many of the cardboard sitcom characters that were on television at the time. Plus, the show was movie-length, and allowed for a level of investment that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise—which actually leads into:

4. Art can be ritual.

The ritualistic aspect of the show has been commented on many times already. Most MSTies can tell you about the first time they saw the show, and many have made it a ritualistic event—getting up to watch it on Sunday mornings, watching it in dorm rooms, and a surprising number of people use it as a nightly sleep aid. But I think the biggest aspect of the show-as-ritual is the cult-like way that people would slowly learn what the show was, and then begin trading tapes and watching communally. The first episode I ever saw was Experiment 508: Operation Double 007, at a slumber party, after all the other kids had passed out. So my first experience of it was sitting eyelash-length from the TV, with the sound as low as possible, laughing into a pillow so I wouldn’t wake anyone else up and get us in trouble. I think the illicit nature of this first viewing that added to my love of the show—it was my thing for a while, because most of my friends didn’t seem to like it the way I did. But, since my family didn’t have Comedy Central, it quickly became a very intense relationship of finding people who had tapes and gathering for weekends (or occasionally skipping school) with people who became my closest friends, who all shared a love of this weird show. This cemented my thoughts about the role art could play in people’s lives, and the sort of bonding that can come only come from suffering through Manos, the Hands of Fate.

5. Never underestimate the intelligence of your audience.

The people who get you will find you, or will be willing to do the work to figure it out. The references in the show are actually important, because they speak to this trust in the audience. Because of their large writing staff, who had a variety of interests, MST3K was written by people who were all reacting to each other as well as the film, and building those interactions into the show. You can go from the name of the Satellite of Love itself, through invention exchanges like Dr. Sax, Tragic Moments, the William Conrad Alert Fridge, and Daktari Stools, to the highly-detailed parodies of Star Trek: Voyager, Planet of the Apes, and 2001, and around to impressions of Tug McGraw and Rollie Fingers, and before you’ve even hit the actual riffs you’ve got a dizzying display of culture, both “high” and “low.” If you get the joke then you get a thrill of knowing that someone else noticed something about culture that you thought was interesting, but if you don’t get the joke, it’s on you to go look it up.

6. American Culture (1950—1990 Edition) was Inexhaustibly Interesting.

My teachers tried their best, but really, if it wasn’t for MST I’d have a pretty bare, bullet-point idea of the 2nd half of the 20th century. Luckily MST3K was there to fill in the gaps. ‘50s sitcoms, Quinn-Martin productions, C-list Japanese monster movies, Zappa lyrics, Aztec theology—I don’t know where I would have been without them. And obviously, when I did get a reference, I got to experience the burst of synaptic joy of being in on the joke.

7. How to Critique American Culture (1950-1990) 101.

Coming to a national network at the very beginning of the ’90s, MST3K stared into the void of our culture, and when that void stared back…Crow said “Bite me.” The writers of the show managed to balance a genuine love of the B-movies they watched with a quick, pointed attack on the movies’ celebration of mediocrity and conformity. Faced with two hours of blonde dullards, they unleashed their full AV geek arsenal, pointing out shallow values systems, kneejerk racism, misogyny, and classism—and also just the basic fact that many of the movies pushed boredom and blind acceptance of the status quo as the solution for all social ills.

8. “It’s just fiction. You don’t have to accept the ending they hand you.”

(Go ahead and skip to 1:27:00, unless you want to watch an unhealthy amount of Jack Elam.)

Probably the most important thing I ever learned. Probably the most important thing anyone can ever learn. As far as I’m concerned, this is the essential lesson of postmodernism, the rise of “geek” culture, fanfiction, Sweded videos, and hell, the whole last half of the 20th century. We are not passive consumers, we don’t have to receive top-down wisdom, we don’t have to roll over and let culture wash over us. You’re pissed off that Sansa Stark is a simpering kid? Re-write her so she’s stronger. You love a movie so much you wish you’d made it? Make your own version with cardboard and duct tape. Maybe it won’t all be good—the Bots’ re-write of Girl in Lover’s Lane is ridiculous—but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try. And if you keep going, you might make something as timeless as Experiment 910: The Final Sacrifice.

Leah Schnelbach should probably repeat to herself it’s just a show…but the part in Laserblast when Mike and the ’bots all become Pure Love and Pure Energy and stuff makes her tear up a little. You can find her not-Tweeting here.