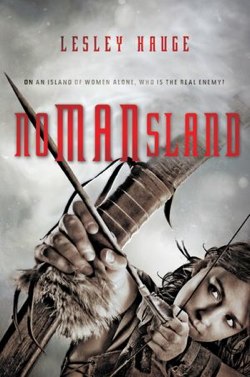

Out in paperback today, take a look at this excerpt from Nomansland by Lesley Hauge:

Sometime in the future, after widespread devastation, a lonely, windswept island in the north is populated solely by women. Among them is a group of teenage Trackers, expert equestrians and archers, whose job is to protect their shores from the enemy—men. When these girls find a buried house from the distant past, they’re fascinated by the strange objects they find—high-heel shoes, magazines, makeup. What do these mysterious artifacts mean? What must the past have been like for those people? And what will happen to their rigid, Spartan society if people find out what they’ve found?

Chapter One

Today Amos, our Instructor, keeps us waiting. Our horses grow impatient, stamping and snorting and tossing their heads. When she does appear, she looks even thinner than usual, her bald head bowed into the wind.

“Tie a knot in your reins,” she barks. “And do not touch them again until I tell you.”

She has not greeted us and this is the only thing she says. Under her arm she carries a bundle of switches, and our unease is further transmitted to the restless horses. It is some years since our palms last blistered with that sudden stripe of pain, a slash from those slender wooden sticks to help us learn what we must know. We’ve learned not to transgress in those girlish ways anymore. As we get older, there seem to be other ways to get things wrong, and other punishments.

Amos goes from rider to rider, pulling a switch from the bundle as she goes, passing each switch through our elbows so that it sits in the crooks of them and lies suspended across our backs. We must balance them thus for the whole of this morning’s instruction. For good measure, Amos tells us to remove our feet from the stirrups as well, so that our legs dangle free and we have nothing to secure us to our horses other than our balance.

“You are my Novices and you will learn to sit up straight if it is the last thing I teach you.” She picks up her own long whip and tells the leader to walk on. We proceed from the yard in single file.

Already the dull pain above my left eye has begun. The anxiety of not knowing what will happen should my switch slip from my clenched elbows, the desperation to get it right, not to get it wrong, throbs in my skull. If we can get away with it, we exchange glances that tell each other our backs have already begun to ache.

The cold has come and the air has turned into icy gauze. In response to the chill wind under his tail, the leader’s horse sidles and skitters, then lowers his head. I wonder if he will buck. Today the leader is Laing. Will she be able to stay on if he does buck? What will be the penalty if she falls? Perhaps a barefoot walk across the frosted fields to bring in the brood mares, or being made to clean the tack outdoors with hands wet from the icy water in the trough. At least we are now spared the usual revolting punishment of cleaning the latrines, a task or punishment that falls to other, lesser workers.

But there is nothing to worry about. Laing is also a Novice like me, but she is far more gifted. She’s what you might call a natural.

“Concentrate on your center of balance.” Amos stands in the middle of the arena and pokes at the sawdust with the handle of her whip, not looking at us as we circle her. From her pocket she takes out her little tin box of tobacco and cigarette papers. With one hand still holding the whip, she uses the other hand to roll the flimsy paper and tamp the tobacco into it. Then she clamps the cigarette between her thin lips.

In my mind I have her fused with tobacco. Her skin is the color of it; she smells of it. I even imagine her bones yellowed by it, and indeed her scrawny frame seems to draw its very sustenance from it. She appears never to have had hair and her eyes are amber, like a cat’s. She rarely eats, just smokes her cigarettes one after the other. Where does she get the illicit tobacco from? And the papers? And from where does she get the courage to do something so disobedient so openly? It is a mystery, but a mystery that we would never dare question. And the little painted tin box in which she keeps her tobacco is another mystery. It is a found object from the Time Before, made by the Old People, who were not like us. “Altoids,” it says on the lid. None of us knows what it means.

Amos has had to drop the whip in order to light the cigarette, but it’s swiftly back in her hand. She sends a lazy flick, the lash moving serpentlike across the sawdust to sting the hocks of my horse.

How does a serpent move? I am not supposed to know because we have never seen such a thing in our land. They do not exist here.

And yet I do know. I know because I read forbidden pages and I saw a forbidden image upon those pages. I saw the creature entwined in the branches of a tree. And I read the words: Now the serpent was more subtil than any beast of the field which the LORD God had made. And he said unto the woman, Yea, hath God said, Ye shall not eat of every tree of the garden?

When I handed those pages back, the Librarian turned white with worry at what she had done, for it was she who had mistakenly given me those pages. But this is how I know things. I know a great deal because I am one of the few who likes to read the pages. There are piles upon piles, all stored, as if they were living things, in wire cages in the Library. No one really likes it that I visit the Library so often, but then there is no real rule that forbids it either. I knew never to tell anyone I had read something not meant for my eyes. I think we are all getting better at keeping secrets. I should be careful what I think about in case it somehow shows.

Amos must have seen me watching her. “Trot on,” she says. “You look like a sack of potatoes.” Again her whip stings my horse and he lurches forward, but she says nothing more, only narrowing her eyes through her own smoke as my horse blunders into the others, who have not speeded up. For a moment there is clumsy confusion as some of the horses muddle about and her silence tells us how stupid we all are, particularly me.

Amos was once one of the best Trackers we have ever had. From her we will learn how to use our crossbows, how to aim from the back of a galloping horse, to turn the animal with just the merest shift of one’s weight. We are getting closer and closer to what will eventually be our real work as Trackers: guarding the borders of our Foundland, assassinating the enemy so that they might not enter and contaminate us. We are women alone upon an island and we have been this way for hundreds of years, ever since the devastation brought about by Tribulation. There are no men in our territory. They are gone. They either died out after Tribulation or they just moved on to parts unknown. As for those who live beyond our borders, the mutants and the deviants, the men who might try to return, we do not allow them in. No man may defile us or enter our community. We fend for ourselves. There are no deviants or mutants among us. No soiled people live here. We are an island of purity and purpose. We must atone for the sins of the people from the Time Before—they who brought about Tribulation.

Our future duties as Trackers seem a lifetime away. For now there is just this: the need to keep my back straight, the need to keep my horse moving forward.

By the time we get into the tack room to finish the day’s cleaning, it has started to snow properly. The horses are all in for the day, brushed down and dozing, waiting for their feed.

The tack room is one of my favorite places. It is a long, low building made of mud and wattle, with a thatched roof and a floor made of yellow pine planks that must have been pulled from some pile of found objects made by the Old People, before Tribulation. Their surface is so smooth, so shiny, not like the rough surfaces we live with most of the time.

The room smells of saddle soap and I love to look at the rows of gleaming saddles and bridles on their pegs. They are precious things. I run my hand over the leather, making sure that no one sees me doing this. Sensuality is one of the Seven Pitfalls: Reflection, Decoration, Coquetry, Triviality, Vivacity, Compliance, and Sensuality. It is, we are told, a system to keep us from the worst in ourselves, and has been thought out by all the leaders of the Committee over all the years we have been forging our lives.

The trouble is that these things are so dev ilishly hard to watch out for, or even to separate from one another (“which is why they are called Pitfalls,” says Parsons, one of the Housekeepers).

Outside the snow flurries and whirls with its own silent energy, and I catch sight of my face in the darkening window. Reflection: I have fallen into two Pitfalls in as many minutes. Nonetheless I stare at it, my eyes large and frightened in this defiance; the broad nose and the wide mouth; my face framed by my wild, coarse black hair, cut to regulation length. I am one of the few whose hair still grows thick.

The Prefect in charge has pulled up a stool in front of the stove in the corner, although she keeps turning to look in my direction.

“Keller!” But she doesn’t bother to move from her cozy spot.

I drop my gaze to my work, rinsing the metal bits in a bucket of water, which is cold and disgusting now with the greenish scum of horse saliva and strands of floating grass.

The door opens and some of the snow blows in. Laing comes in too, stamping the snow off her boots. She is carrying a saddle, which she loads onto its peg.

Laing is, and no other word suffices, beautiful. We are not allowed to say these things, of course, but everyone knows it. She has a sheaf of silver-blond hair, albeit only regulation length, but even more abundant than mine. She is, if anything, slightly taller than I am. Although her complexion is pale, she has surprising black eyebrows and eyelashes that frame eyes so dark blue that in certain light they almost seem violet. Her carriage indicates the way she is, haughty and rather full of herself. She takes a moment to stare, both at me and the mess in the bucket, and says, “You should get some clean water.”

“I’m almost done,” I answer, but she is already walking away. “Laing, do you want to wait up and then we can walk back to the Dwellings together?” I don’t know why I suggest this. Although she is in my Patrol, I would not exactly call Laing my friend. We are not allowed friends, anyway.

She stops and turns quite slowly, quite deliberately, and says with what I can only say is some peculiar mixture of determination and exultation, “My name is not Laing.” She hesitates for only a moment and then hisses, “It is Brandi.”

Glancing back to make sure the Prefect does not see us, she advances toward the window, which is now steamed up with condensation. She catches my eye and begins to write the word BRANDI on the windowpane.

It is all I can do not to gasp at the sin of it, the forbidden i or y endings to our names and indeed the very falsehood of it. There’s no way in hell she could be called that name. But there it is, written for all to see, in trickling letters on the windowpane. I am so shocked that I do not even move to rub it out, surely the prudent thing to do. But she knows how far she can go, and before I can move, she sweeps her hand over the forbidden name, leaving nothing more than a wet arc on the steamy surface. She turns and suddenly smiles at me and puts her finger to her lips.

“Our secret,” she says. “I’ll meet you outside when you’ve finished.”

I look quickly at the mark in the window where she wrote the name, willing it to steam back up again. If the Prefect asks what we were doing, messing about back here, I will be hard put to make up anything.

After drying and polishing the remaining few bits and buckling them back into the bridles, my heart is pounding and my fingers do not work as fast as they should. The throbbing above my left eye, which had eased, returns.

For there was something else that Laing had displayed, not just the peculiar, transgressive name marked on the window, but something I couldn’t even place or classify. When she wrote the name on the window, I saw something completely new to me. There, on her finger, was an extremely long, single curved fingernail painted a shade of dark pink that somehow also sparkled with gold. When she held her finger to her lips, it was that finger she showed me, the nail like some kind of polished, spangled talon.

I have never seen anything like it.

Chapter Two

The wearying ride, my throbbing head, and the worry about Laing’s inexplicable (and stupid) behavior in the tack room have exhausted me. But before I can sleep I have to endure Inspection, which is always a dreary, pointless affair.

Every night the Prefects come into our Dormitory, and the first thing they do is fill in the menstruation charts and allocate sanitary belts and napkins to those who need them. If more than three of us are cycling together, the Headmistress must be notified, for that could mean a fertility wave is in progress and the Committee Members from Johns, the place from which we are governed, must be sent for in order to commence impregnation. But this hardly ever happens to us. I don’t even know why they log our cycles, since the Patrol is almost always spared. We are too important because we are meant to guard the borders, not to breed. Still, they like to know our cycles. They like to know everything.

The Prefects carry out a number of mostly petty duties. I can’t say that I respect them in the same way I would respect an Instructor, but you have to do as they say. They monitor our behavior and report everything to the Headmistress. And they administer many of the punishments.

When the Prefects are not breathing down our necks (and when they are not breathing down the necks of the Novices and Apprentices in the other Orders— Seamstresses, Nurses, and so forth), they do have another duty. They are supposed to search for found objects from the Time Before. But those finds are so rare now that they have almost ceased searching for them, which means they have even more time to pester us, such as now, at Inspection.

Tonight, as every night, they check us for general cleanliness and they inspect our hands and feet. The other thing they do, which they seem to enjoy the most, is make sure no fads have arisen. It is the Prefects’ duty to “nip them in the bud,” as they like to say.

A few weeks ago there was a fad for pushing up the sleeves of your jacket to just below your elbow, and there is one that is gaining popularity, which is to bite your lips hard and pinch your own cheeks to make the skin bright red. Well, that one comes and goes quite regularly because it is harder for the Prefects to spot. There are so many rules. What ever we do, whether we overstep or stay within the lines, we are kept in a perpetual dance of uncertainty in these matters.

Tonight the Dormitory is particularly cold and we want to get into bed. Three Prefects, Proctor, Bayles, and Ross from the tack room, march into the Dormitory, flapping the menstruation charts and taking out their tape measures. Tonight they are checking to make sure our hair has not exceeded regulation length. They do this every so often when they suspect that those who have thick hair have let it grow beyond shoulder-length. Long hair is a dreadful vanity, they say, falling somewhere in the Pitfalls between Reflection and Triviality.

Proctor is still fussing with her chart as Bayles starts to make her way down the line with her tape measure. Bayles is taller than the average Prefect but is still shorter than I am. She is heavily built, has hair like wheat stubble, and she has to wear thick eyeglasses. She yaws at me with her buckteeth and her eyes are grotesquely magnified behind the lenses of her ugly eyeglasses. The Nurses must have supplied her with them from some store of found objects; I do not think we have figured out how to make that kind of glass.

I dread the moment when Laing will be required to show her hands. Is that pink claw still there? I don’t know how to explain it. Where did she get it?

Bayles takes up a position in front of Laing, her stubby legs planted far apart, staring at her, but Laing just looks over her head as if Bayles were not there.

“You have let your hair grow past the regulation length again,” says Bayles. “You are vain.” She waits for a response but there is none. “You think you are someone special, don’t you?”

Laing still refuses to look at her.

“You will rise half an hour earlier and come down and have one of the Housekeepers cut your hair.” Bayles takes a handful of it and yanks Laing’s head back. “It’s a good inch too long,” she snaps. She peers into Laing’s face. “I could tell them to cut the lot off.” Her eyes swim and roll about behind the thick lenses as she glares at me because I am craning forward. She turns her attention back to Laing. “Feet,” she says and looks down. Our feet, which are bare, have turned blue. “Hands.”

Laing holds out her hands, palms facing up. Again I turn my head in her direction as far as I can without being noticed. “Other way,” says Bayles, and Laing turns her hands over. “Proctor,” says Bayles, “come and look at this.”

Both Proctor and Ross, who have heard that dangerous “aha” note in Bayles’s voice, come hurrying over and together all three of them pore over one of Laing’s fingernails.

“What is that white line?” asks Proctor. “Here, this line here, by the cuticle.” Proctor has pincered the offending finger between her own thumb and forefinger, and her brow is furrowed as she bends over Laing’s hand. Bayles and Ross have swelled with the importance of the discovery, their expressions a mixture of bossy importance and sheer delight. “What is it?” says Proctor again.

Laing sighs as if she were bored and tries to reclaim her finger from Proctor’s grasp. For an instant they tug back and forth but in the end Proctor lets go.

There is silence and we all wait in the chill, tense atmosphere.

Laing looks over the Prefects’ heads again and down the line at all of us. Unbelievably, she winks at me. A ripple of apprehension runs down the line. She splays her hand again, inspecting her nails herself, tilting them this way and that. And then she yawns.

Proctor reddens with anger. “What is that stuff on your fingernail?”

“Glue,” says Laing.

Proctor blinks stupidly at her. “Glue?”

“After supper, I was helping the Housekeepers paste coupons into their ration books. I guess I just didn’t wash it all off.”

Proctor takes the finger again. With her own finger, she picks at the offending line of white stuff. It is indeed resinous and sticky.

When at last they leave, we are free to snuff out the oil lamps and fall into bed. The wind howls outside, and the snow must now be piling in drifts against the walls and the fences we have built to protect our lands and to keep things in order.

Nomansland © 2011 Lesley Hauge