There’s a lot of buzz lately about the phenomenon of “Young Adult” and “Middle Grade” audiences and their purchasing power. Fans of genre writing have watched writers like J.K. Rowling be propelled to superstardom supposedly via legions of adoring teen and pre-teen fans. Some of our dearest genre favorites, envelope-pushers like Paolo Bacigalupi and China Mieville have gotten in on the act to great acclaim.

Some hard core speculative fiction mavens turn their noses up at “kids stuff,” only to quietly insist on taking their own kids to the latest Pixar flick “you know, because they need adult supervision.”

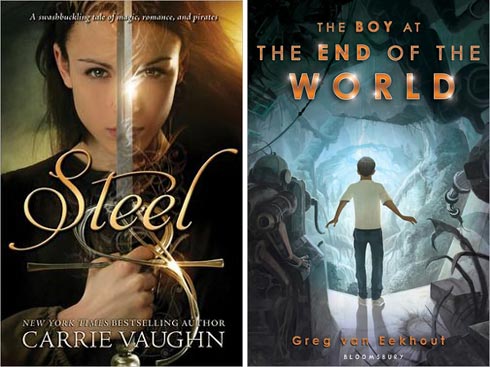

What’s at the bottom of it? No one can deny that the so-called YA and MG audiences do demand special kinds of writing and are large enough of an audience to command serious attention from publishing houses. We asked two up and coming YA/MG genre writers, Greg Van Eekhout and Carrie Vaughn to discuss how they approach their audience.

Myke: An SF/F author recently told me that he deliberately wrote a YA book because he felt it would cement his career financially, and in terms of sales numbers (giving his publisher confidence that he was a big seller). He also stated that he felt he had a much bigger chance of making the NYT bestseller list with a YA novel.

Do you think this is a reasonable position? If so, why or why not? Why is YA so much more popular/high-selling in the SF/F genre than so called “adult” works (keep in mind that some so called “adult” works like Ender’s Game are later simply repackaged and sold as YA, and many so-called YA works sell quite well to older readers)?

Greg: I get a lot of emails like that. “Hey, I hear YA is the New Big Thing and I’ve read three whole YA books, so do you have any advice?” Barf. I think there’s only one reason to write in any genre or to any particular age group: You are called to it. You think it’d be fun. Books like the kind you are writing have had an impact on you. You feel you have an affinity for the audience. Yes, there are many successful YA books now. There are also many YA books that sink commercially. Most of them sink commercially. That’s how publishing works, no matter what the genre or age range. Or maybe there’s something about YA that I don’t know, because I don’t write YA, I write books for adult audiences and other books for middle-grade audiences. Carrie?

Carrie: I admit, I’m suspicious of any career planning that involves chasing the next “big thing,” just because it’s so hard to predict what the next big thing is going to be a couple of years—or even six months—out. One thing that attracts writers to YA is that (at least in my experience) the subject-matter boundaries are not as rigid as they are in SF&F. You can write SF, or fantasy, or contemporary with fairies, or historical with steampunk mecha, and it’s all YA. It’s marketed as YA, whereas in SF&F publishers seem to get nervous if you start crossing so many genre lines that they don’t know how to market the thing. But as you say, Greg, ultimately book sales defy marketing, and there are plenty of adults reading Twilight and plenty of teens reading Stephen King. Just writing a YA book is not going to guarantee career stability or anything else. Write a book, then write the next one, etc.

I didn’t plan to write YA—I had a story that simply wasn’t working as a straight-up fantasy novel. But when I made made virgin sacrifice part of the plot, and made the main character a contemporary teenager dealing with her first boyfriend, whether or not to become sexually active, and so on, writing the novel as YA seemed not just a good idea, but imperative. I’ve since decided that it’s a mission of mine to write books starring teen girl characters having awesome adventures that don’t involve getting a boyfriend by the end. So yes, I think I’ve been called to it. Robin McKinley’s The Blue Sword was a defining book of my teen years, and I’d love to have more books like that in the world. And back to the original question, The Blue Sword is another one that gets shelved in both SF&F and YA. McKinley’s a Newbery winner and considered a YA author, but her books are universal. It’s all about the story, not the marketing category. Or ought to be.

Myke: Okay, so you both seem to agree that your writing takes you in the direction that it takes you, and that trying to direct yourself specifically for reasons other than artistry is a bad idea (this is a variation on the age old “write what you like or write for the market” debate).

So, let me ask you this: Regardless of your decision to NOT specifically write YA because it is lucrative, do you think it actually is lucrative? Is it really a larger market than so-called “adult” SF/F? Does this mean that younger people read more genre fiction? If so, why? What’s going on here?

And most importantly, what does that tell you about the YA audience?

Greg: First, I want to follow up to Carrie’s answer.

I want to pick up on what Carrie said, but first I think we need to make clear the distinction between YA and middle grade, because they’re not the same thing. Middle-grade, as a marketing category, is aimed at readers from 8 to 12, with some wiggle room in either direction. Young Adult is targeted at teenagers. In both cases, the readership spans from considerably younger to full-grown adults. In terms of the how middle grade and young adult are qualitatively different from one another and from adult fiction, I hope we can touch on that during this conversation.

Anyway, in talking to a lot of middle grade and YA writers, I’ve noticed a lot of them are like Carrie, in that they have specific goals for the kinds of characters they want to write about, and these goals are closely tied in to the age of the audience they’re writing for. In Carrie’s case it’s teen girls having awesome adventures. In my case, it’s readers who identify with smart kids who haven’t yet found their tribe. That can be a lonely time in life. It’s important to me to write about it. The best, most direct way I can figure to write about it is to write books specifically aimed at that age group.

—okay, my answer to your second question—

Okay, just some raw numbers. According to the American Booksellers Association, in 2010, all children’s and YA hardcovers were up 0.2 percent, to $59.7 million. Adult hardcover was up 23.1 percent, to $148.2 million. Anyone who’s really interested could get more numbers sorted by genre category.

I’m much more interested in what YA does well in terms of communicating with its audience. And I think, at least in terms of genre, it’s this: adult science fiction, and fantasy to a lesser extent, is largely concerned with having a conversation with itself. You present an idea, say, oh, sentient planets. And what devoted readers will do is compare and contrast what you have to say about sentient planets to what other writers have said about sentient planets. And that’s a big part of SF’s appeal. It’s part of what makes it rich and fun. But it’s easy to forget that some readers haven’t been having that conversation about sentient planets for the last few decades of their lives, because they’re less than two decades old. What a lot of YA does better than a lot of adult SF is tell engaging stories with complex ideas, but ones that don’t assume the reader’s been digging this stuff for years and years. That’s not to say YA SF is dumbed-down SF. It just takes a different approach. A more welcoming approach, in a lot of cases. Which is maybe why YA is popular not just with teens, but also with many, many adults. But, yo, I’m not bashing adult SF. Carrie and I both write for adults. I won’t presume to speak for Carrie, but grown-up books are still fun.

Carrie: There are also some structural differences between middle grade and YA—word length, chapter length. But I tend not to worry about that, and tell other people not to worry to much, because as Greg said, the audience and themes of the book—and how the audience relates to those themes—is more important.

On a purely personal level, my urban fantasy series—marketed as adult SF&F—sells a lot more than my young adult books. But there are too many variables to make sweeping generalizations—do the Kitty books sell well because it’s a long-standing ongoing series? Because urban fantasy with vampires and werewolves is still so popular? Because there are actually a lot of teens reading it even though it isn’t strictly YA? What’s interesting to me is how many vampire/urban fantasy authors are writing young adult series as well, often set in the same world as their adult books, but focused on a younger audience. At least in this area, there’s a huge amount of crossover.

And this brings me to my answer, which is how hard it is to put boxes around any of this. The massively bestselling series for younger readers—middle grade or YA—are massively bestselling because everyone reads them. Because they find an audience outside the marketing category. The last Harry Potter book didn’t sell millions of copies to just teenagers. By the same token, kids read anything and everything. Plenty of teens don’t read YA at all and jump straight into SF&F. I hesitate to separate the younger audiences from adult audiences quite so much. I think genre fiction across the board is hugely popular right now, with a big boost from cable TV. Charlaine Harris and George R.R. Martin are selling a huge number of books, thanks to the TV series based on their books. So I don’t think kids read more genre books than anyone else. But I do think they’re open to more different reading experiences than adult audiences. That’s just the nature of being a kid who’s ready to sponge up the world.

So, to really hit the jackpot you need to write a book that appeals to teens and adults, and gets a premium cable TV series. Bingo!

Seriously, though, there’s definitely a perception that the young reader market is more lucrative, for a lot of reasons. High-visibility series like Harry Potter, Twilight, as well as a dozen other series (how many of which have been made into movies?) have made YA very popular for publishers and writers. Everyone’s looking for the next Harry Potter. But I think the category has a lot of thematic freedom that writers find attractive. As Greg said, you’re not expected to be in dialog with a century’s worth of previous work. You don’t have to worry so much about fitting into a specific sub-genre. You can focus on one character and one adventure, rather than the complexity of a dozen subplots. From a strictly mercenary standpoint I think the young reader market is also seen as being lucrative because of the potential sales to libraries, and the fact that the awards are much more visible, and winning one can guarantee backlist sales for decades. But once again, getting into the market chasing after those goals is kind of like playing roulette by putting your chip on the same spot a hundred times in a row. Maybe you’ll hit, probably you won’t.

Myke: I do want to get into the distinction between YA and MG, but first, I want to revisit a point both of you have touched on: this is the idea that YA is liberated from “having a conversation with itself” as Greg said. It breaks away from the academic style of dealing with a “century’s worth of previous work.”

This is an interesting idea, but is it really the case? There is a huge body of incredibly successful YA out there in the deep, dark past. (I’m thinking Lloyd Alexander and John Christopher. Tolkien was originally sold as a children’s writer. Ender’s Game has been repackaged as YA. And what about Richard Adams? Or Brian Jacques?) Do these influences or others like them really not steer your work?

And, if this were really true, then why isn’t all YA far-flung China Mieville stuff? Pushing the envelope so hard that it’s nearly unrecognizable?

Please expand on this a little more.

Greg: I’m not saying youth literature doesn’t draw from the deep well of myth and legend and folklore and medieval literature and classics and contemporary literature. Conversation with antecedent is taking place, definitely. But I think the conversation is more evident, observable, explicit, with adult science fiction and fantasy. I think the conversation is part of what readers want from SF written for adults. I don’t think that’s true with youth literature. When kids read Hunger Games, they don’t need to care or know about Running Man. They don’t have to have a conversation with Arnold Schwarzenegger. If Hunger Games were written for adult science fiction readers, I think there’d be an expectation to engage in dialog with Arnie and Richard Dawson and probably decades of “most dangerous game” stories. Some might argue that an adult Hunger Games would be a deeper, richer, more complicated book. Others might argue that not being directly engaged with the conversation makes it a fresher, more relevant, more vital book.

Carrie: YA certainly doesn’t exist in a vacuum, but I think the expectations for it are different, and the boundaries are different. So as to why it isn’t all far-flung envelope-pushing work (though some of it is)—I’d say it actually goes in the opposite direction. It tends to focus on individual, single-thread storylines that run from point A to point B. YA is allowed to be unapologetic and honest about dealing with very classic tropes like coming-of-age and adventure quest stories. (Whereas in adult SF&F there often seems to be some kind of irony or in-joke winking involved in telling classic stories.)

Myke: That’s actually a really good segue into a discussion of the difference between YA and MG. You’ve laid out a good definition for YA here (focus on individual, single-thread storylines, unapologetic treatment of tropes—Greg, feel free to amend this definition if you disagree). Does this also apply to MG? You’re dealing with differences in ages, obviously. Does that necessarily mean differences in expectations? And if so, how do you deal with those?

I’m particularly interested in your answers here because you both came out pretty strong for letting your art guide you vice writing specifically to the market. But, surely you write cognizant of your audience? Or am I totally off base here? Either way, there’s clearly a difference in writing for these distinct groups. Please dig in to what you perceive that difference to be and how you address it.

Greg: Let’s just take as a given that a lot of middle grade will have characteristics of YA and vice versa, and there’s a danger of drawing borders with too dark a Sharpie. But here’re some ways of looking at the difference. Garth Nix says middle grade is a subset of children’s literature, and YA is a subset of adult literature, and I think that’s a cool way of looking at it. The Harry Potter phenomenon is interesting, because it starts off clearly as middle grade, with Harry finding his tribe and his core identity. By the seventh book, it’s become YA, and he’s essentially become the person he’s going to be as an adult. In the middle, snogging is discovered.

Middle grade fiction, to me, is really about emergence of self. It’s about expressing the idea that the world is going to start affecting you more, and your parents’ influence is going to wane. Middle grade is when a lot of kids discover their passions—art, music, sports, what have you. So, it’s a perfect time to make some friends and allies and step out into the bigger world and have some adventures.

Middle grade has much more restriction in terms of sex and profanity. A couple of years ago, “The Higher Power of Lucky” by Susan Patron was awarded a Newbery Medal, which is one of the most prestigious awards for middle-grade fiction. The word “scrotum” appears in it, and from the uproar you would have thought Susan Patron had killed all the whales. I would imagine the word “scrotum” appears in YA lit about 4800 times per year.

I think the stakes in middle-grade fiction probably tend to be a bit bigger. I think there might be a bit more world-saving in middle grade.

Carrie: When writing YA I’m cognizant of the audience the way I’m cognizant of the audience no matter what I write. When I write fiction I’m always thinking, “What would I do in this situation? What would someone like this do in this situation? What would make sense to the reader? Does this make sense to an average reader?” With YA it’s just the same, but amended slightly: “What would I have done when I was 16? What would make sense to a 16 year old?” As always, I have to absolutely treat that audience with respect.

This may be one of the tough things about writing for kids: taking them and their problems seriously. Kids are used to adults blowing them off and saying things like “You’ll understand when you’re older,” or even the utterly horrific “These are the best years of your life.” (I had a high school guidance counselor say that to me when I was 17. What I wanted to reply was, “Then slit my wrists now and get it over with, because if it doesn’t get better than this there’s no point.”) If kids sense those kinds of condescending attitudes coming through in a novel that’s supposedly written for them, they’ll be merciless in their derision.

What kids are looking for in books is what we’re all looking for: something that makes them think and feel, that says “You’re not alone, other people go through this too,” and that there’s a big, fascinating world out there to explore. Teens and pre-teens are starting to figure things out, and they have real opinions that they’ve formed by looking at the world. They may not have a whole lot of experience, but they’re smart. Books about them and for them need to reflect that.

Myke: So, now you’ve presented some pretty solid definitions for the difference between YA and MG. Well, Carrie has talked more about how she is cognizant of what kids want in a book. *smiles*

I’m hoping now you’ll connect this specifically to your own work. You’ve already touched on this a bit in the conversation already, but can you now give specific examples of how your own writing addresses some of the items you’ve described? (For example, how you create the higher stakes you see in MG fiction, or how you treat a YA audience with respect.) If you can, would you be willing to stick to published work? I think it would be more interesting for readers to see your comments here, then see them reflected in your books.

Greg: The stakes in my books tend to be kind of ridiculously high. In Kid vs. Squid, the question is whether or not the California coast will be subsumed by the ocean in favor of the creation of a new Atlantis. In The Boy at the End of the World, what’s at stake is the survival of the human species. The kids in my books are saving the world. They’re saving their friends, their families, they’re communities. Big, big, honkin’ big stakes. The challenge isn’t really raising the stakes as much as it is making sure I’m still telling stories about human beings. So, while the characters are dealing with huge things, they’re also grappling with personal foibles, defining relationships, all the stuff that properly goes into stories about people. I think Carrie’s absolutely right that kids are looking for the same things in books that adults are looking for: a narrative experience that expresses a human experience. Whether you’re telling a big story or a little story, powerful fiction is driven by character.

Carrie: The stakes in my own young adult books haven’t been quite so high. I try to do a couple of things with my teen characters—take their problems and feelings seriously, and show them engaged with the world around them. I remember being the kind of teenager who really thought I could go out and change the world and do magnificent great things. It didn’t take long for reality to disabuse me of that notion—or to at least scale it down. “Saving the world” morphed into “be a writer.” But since there were lots of people telling me I couldn’t be a writer either, pursuing that goal became an epic struggle in its own right. One of the great things about genre fiction is I can have a teenage character who wants to change the world, or save the world—and she really can.

A personal example: I was a senior in high school during the Gulf War, and it was huge for me. It felt like the most important thing that had ever happened in the world in my whole life. I was really politically engaged through it, writing letters to the editor of the local paper, staging protests, arguing against it at my uber-conservative high school. I’m sure I came across as being naïve and silly about the whole thing. But the thing is, I really wanted to make a difference, and I thought I could change people’s minds. Never mind that I didn’t. But it only took one person—a college professor who was on a committee for a scholarship I had applied for—to hear my opinions, look me in the eye and say “I think you’re right” to validate everything I was feeling. I know from experience that a book, the right book, can do that for someone, too.

Moving on to Voices of Dragons, my main character Kay takes it upon herself to stop a war. It’s a war between humanity and dragon-kind (in an alternate reality where the Cold War happens between dragons and humans), but it’s still a war. She believes she has the tools to make a difference—her clandestine friendship with the dragon, Artegal. And she’s right. So she really is saving the world, or at least her corner of it, and she’s also dealing with her feelings for her first boyfriend and how far to take the relationship (which I hope is a familiar experience for at least a few of the kids reading the book). Basically, Kay’s dealing with a huge amount of stuff in her world. I hope that makes her sympathetic and relatable to just about anyone.

A more general take: the issue of romance comes up a lot in YA, and not just because of Twilight, but because it’s a really big deal for teens. When you’re 16 and falling in love for the first time, or having your heart broken for the first time, it’s epic. It’s huge. It feels like the world is shuddering on its axis. Because you’ve literally never felt anything like it before. Now, as adults we know that kid is probably going to go through love and heartbreak several more times—maybe many more times—over the next however many years. But that doesn’t, or shouldn’t, take away from how huge it feels when it happens for the first time. It’s quite a powerful thing to write about as well, which is why I think so many writers like doing it.

Myke: Whether it be the fate of the world or the outcome of a first romance, you’re still reaching into a world that isn’t yours (at the present moment, I mean). You’re adults and you’re (through your writing) reaching out to people who are different from you—in this case (YA and MG aged readers).

If this question is too personal, feel free to shut me down, but I want to know how your personal experiences as an adult relating to YA and MG aged folks has colored your ability to write for them. Are there lessons you learned through dealing with your own children (or cousins, or nieces and nephews, or kids you mentor, etc . . .) that have made you better at writing for them? Maybe it’s muddied the waters? I’d prefer to hear specifics or anecdotes if you’ve got any.

Greg: I tend to think that everyone’s different from me, not just kids. It’s possible I’m a weird person, you know, and if I could only write for people who are like me, I wouldn’t have any audience at all. Ultimately, I’m my audience. I’m writing stories for myself. I don’t have kids of my own and I don’t hang around kids all that much. Maybe that puts me at a disadvantage. I know I’ve talked about particular characteristics of middle-grade readers, but I don’t think about that when I’m writing. Honestly, I try not to overthink the audience at all when I’m writing. I feel connected to who I was when I was ten or twelve, more than to who I was when I was seventeen. It’s just a time in my life that’s not difficult for me to tap. Maybe I’m contradicting things I said earlier, but I hear people talk about what kids are like, and it sounds like they’re listing behavioral characteristics of dog breeds. Retrievers have an affinity for water. Eleven-year-olds like gum. It’s more complicated than that. Kids are individuals and they come in a billion varieties. I think I have a voice that works for middle grade. I suppose it’s possible to develop a voice through study, but I wouldn’t even know how to begin. It’s more of an instinctive thing for me.

Carrie: You want personal, I’ll tell you the absolute worst thing I’ve ever said to a teenager. The teen in question is the daughter of a good friend of mine (like Greg, I don’t have kids), about 16 at the time, and she was telling us about how she didn’t really like the latest Harry Potter book because the characters were all just too whiney and angst ridden. And I said, “It’s like hanging out with you.” I immediately hugged her and told her I loved her, and she gave me a dirty look and called me names for a while. She’s now 21 and a genius young artist—she took the author picture on my books—and we’ve spent a lot of time talking about creativity, making creativity your job, and so on. So we’re still friends, which makes me happy.

That really has nothing to do with my writing, it’s just me behaving badly and showing that teens and adults can be friends. There really hasn’t been anything a kid in my life has done that made me think, “Aha! I need to put this in my next book.” The closest is the time I spent at a fencing school in Boulder that produces internationally-ranked junior fencers on a regular basis. What that did was show me that internationally-ranked teen fencers exist, so I could make the main character of Steel (my second YA book) a 16-year old competitive fencer. But that was more like writing about a specific job than about kids in general.

Like Greg, I mostly draw on my own experiences and memories of being a kid. This is something I can do when I’m writing about kids that I can’t do with any other identity I might be writing about—I used to be a kid. Every single person in the world used to be a kid. How cool is that? That’s why books for kids are also for everyone.

Myke: I want to thank both of you for taking the time to talk about this. Since you’re both YA/MG authors, this conversation has mostly revolved around your writing in that arena and how your relationships and experiences have shaped it. As a final question, I wanted to throw it open to you. Is there anything in closing that you’d like to throw out there, even if it has nothing to do with YA/MG topics?

Greg: My still-young novel career so far has been middle grade books, bracketed by adult novels, if you count the book currently in progress. Maybe it’s because whatever thing I’m currently working on always feels like an epic struggle and I’m just punch drunk, but I feel smarter when I’m writing middle grade. I think I may have been smarter when I was that age. I think when I’m writing middle grade, I’m doing what I was meant to do. Writing for adults fulfills a very real need, and I hope to write YA at some point, but middle grade feels like me at my most natural. And I’m wondering if Carrie feels something similar when she’s writing YA.

Carrie: I’m glad I fell into writing YA. It wasn’t something I imagined for myself ten years ago, but now I have a list of YA stories I want to write, since I’ve been introduced to that world. It just expands the playgrounds I can play in, and I love that.

The Boy at the End of the World is currently on sale in its ebook format until 7/5.

Myke Cole is the author of the military fantasy SHADOW OPS series. The first novel, CONTROL POINT, is coming from Ace in February 2012.

Greg van Eekhout writes books for kids and adults. He is the author of the middle-grade novels Kid vs. Squid, The Boy at the End of the World, and the mythological fantasy novel Norse Code, as well as about two-dozen short stories. His website is www.writingandsnacks.com.

Carrie Vaughn was born in California, but grew up all over the country, a bona fide Air Force Brat. She currently lives in Colorado, with her miniature American Eskimo dog, Lily. She has a Masters in English Lit, loves to travel, loves movies, plays, music, just about anything, and is known to occasionally pick up a rapier.She’s never been a DJ, but loves writing about one. Her website iswww.carrievaughn.com.