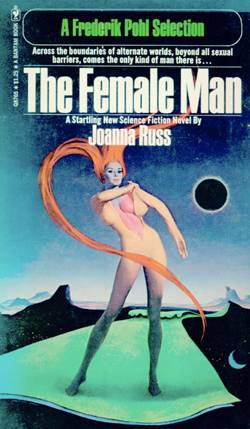

The past few reviews in the Queering SFF series have been of new books (such as Amanda Downum’s The Bone Palace), and since these posts are intended to gather history as much as they are to introduce new work, today we’re jumping back in time to the 1970s. Specifically, to one of Joanna Russ’s most famous works, her novel The Female Man, and the companion short story set in the world of Whileaway, “When it Changed.”

“When it Changed” was nominated for the 1973 Hugo Award and won the 1972 Nebula Award. It’s also been given a retroactive James Tiptree Jr. Award. The Female Man, too, was given a retroactive Tiptree Award, and on its publication in 1975 it was nominated for a Nebula.

Which isn’t to say that the reception in the community was entirely positive. Award nominations are intriguing—for one, because they show works of lesbian feminist SF getting recognition—but there’s more to the story.

Helen Merrick’s indispensible book, The Secret Feminist Cabal, touches multiple times on Russ and reactions to her work—including The Female Man and “When it Changed.” In a section titled “Contesting the texts of feminist SF,” Merrick lays out various heated exchanges from fanzines of the time. She also considers published reviews of The Female Man and Russ’s own aside within the novel about how reviewers were likely to respond to the work (which is devastatingly genius and I will talk about it in a moment).

One set of letters from a fanzine title The Alien Critic is particularly wince-inducing, in response to “When it Changed.” The story is described with words like “sickening.” The conclusion reached by the man writing the letter just has to be quoted for you to really grasp how stupid it was—Merrick also quotes it at length for the full effect. He says,

The hatred, the destructiveness that comes out in the story makes me sick for humanity and I have to remember, I have to tell myself that it isn’t humanity speaking—it’s just one bigot. Now I’ve just come from the West Indies, where I spent three years being hated merely because my skin was white—and for no other reason. Now I pick up A, DV [Again, Dangerous Visions] and find that I am hated for another reason—because Joanna Russ hasn’t got a prick. (65)

I wish I could say that I find that response as dated as it is awful, but really, I’m pretty sure we have this fight every month on the vast and cosmic internet. It’s just easier and quicker to yell stupid things now that you don’t have to write them out and mail them. QSFF has certainly provoked some similar responses, within the posts and on outside blogs.

So, despite its awards and nominations, “When it Changed” was not universally loved. It provoked nasty responses from other people in the SF field. I find that tension remarkably intriguing. On the one hand, it thrills the heart to see a work of lesbian feminist SF receive recognition. On the other, it’s so discouraging to see that the negative responses are essentially still the same, and this was nearly forty years ago.

The critical response to the text also varied. Some people, obviously, loved it. The book was a massive deconstruction of SF and its tropes. It threw received ideas about novel plotting out the window. It was postmodern; it was challenging; it wasn’t a book that people could pick up, read in a day, and forget immediately. Merrick’s collection of criticisms from reviews is eerie, because they nearly echo Russ-the-author/narrator’s own imagination of the response to the novel. It wasn’t a real novel, it wasn’t SF, it wasn’t anything, many critics said. Some managed to attack the structure instead of the content, but the undercurrent of deep unease is clear—and sometimes outright anger.

Russ’s own address to the reader begins: “We would gladly have listened to her (they said) if only she had spoken like a lady. But they are liars and the truth is not in them.” She goes on for the next page with phrases, clips and chunks of criticism she expects for her “unladylike” book:

shrill…vituperative… maunderings of antiquated feminism… needs a good lay… another tract for the trashcan… women’s limited experience… a not very appealing aggressiveness… the usual boring obligatory references to Lesbianism… denial of the profound sexual polarity which… unfortunately sexless in its outlook…

She finishes, “Q. E. D. Quod erat demonstrandum. It has been proved.” (140-141)

I picked out a few of the choice ones from the list, like the accusations of sexlessness or of “boring” lesbianism. These are criticism that have been made of books about women’s sexuality and lesbian experience before. It’s not like Russ pulled them out of thin air. Hardly.

But, but—it was a nominee for the Nebula. Russ’s peers respected and enjoyed the book enough to nominate it for one of the genre’s biggest awards. (Notably, it was not nominated for the Hugo, the popular vote award. I’m not sure if I can safely draw any conclusions there, but it seems a bit suggestive.)

It likely helped that radical feminism in the 1970s was a wild and active thing. In the backlash of the late eighties and early nineties, the reception for The Female Man might have been considerably different—worse, even. I also find it interesting in a not-so-good way that most of the reviews Merrick quotes never engage with the idea of sexuality in the book, and seemingly, neither do those negative reviews of “When it Changed.” The complainants are constantly framing Russ’s text in reference to men, to male sexuality (specifically, heterosexuality), to their own male bodies, to penises. While Merrick’s book is obviously about feminism and not queer issues—it would be twice the size and unwieldy if she tried to tackle both—when I read these texts, I could not see them as anything other than queer fiction. The criticism and recollection of Russ’s work today tends to focus on her feminism to the exclusion of sexuality: it’s as if we still think the “l”-word is a negative thing to apply to a scholar and writer, or to her work. (Which is actually remarkably true in the scholarly/critical world, but that’s a post for another time.)

But these stories aren’t just works of feminist praxis. They are more.

The Female Man and “When it Changed” are queer stories—they are lesbian stories, and also stories of “women’s sexuality” across a spectrum. They are stories about women loving, touching, needing, lusting for and getting physical with other women. They are stories about women together, erotically and emotionally. They are not boring and they are not sexless. They are as queer as they are feminist, and I think that not discussing that does them and the author a severe disservice.

So, that’s what we’re going to do, now. Placing texts where they belong in history is an act of reclamation, and that’s what we’re all about here. To “queer science fiction and fantasy” is to do more than just say “we’re here, we’re here.” It’s also to say “we were here, we have always been here, and look at what we made.” In that spirit, I’d like to discuss The Female Man both as a novel and as a work of queer science-fiction.

*

The first thing I will say is that this is not an easy book, in any sense of the word. It is a difficult book—emotionally, narratively, in every way. For such a slim tome, it takes much longer to digest than books four times its size. That’s what blew me away about it, though; the challenge, and the rewards that come from meeting that challenge.

On a basic level, there is a challenge in the reading of it. The text is organized in constantly shifting narrative points of view, often with few tags to indicate who is speaking or where or even when or what world they’re in. (At one point, the character Laura gets a first-person bit, which throws off the previous pattern of only the J’s—Joanna, Janet, Jeanine and Jael—speaking to the reader. There are also the direct addresses from the author that pop up here and there.) The idea of “I” is put to the test in The Female Man. What or who is “I?” What makes one an “I” instead of a third person “Jeanine?” For a reader familiar with postmodernism, this won’t be as challenging as it will be for someone who isn’t prepared to let go during the act of reading.

It sounds kitsch, but you really do have to let go of your expectations and your attempts to weave a narrative framework in your head for this book. Just let it happen. Go with it. Don’t worry too much about which “I” is “I” or when or where; things will become clear in time.

I love this kind of thing, when it’s done well, and Russ does it very well. It gives the brain a workout. The book is also extremely vivid and detail-oriented; never does Russ under- or over-describe a scene, whether it’s page-long paragraphs of inner monologue or dialogue-only confrontations or sweeping passages of world-building or sparse but supremely effective erotic descriptions. It’s a gorgeous book, frankly, and well worth any reader’s time.

Aside from that basic narrative challenge, the book is tough emotionally. It is hard to read; sometimes it overflows with anguish and terror and rage to the extent that I had to put it down to catch my breath before it drew me inexorably back in. The fact that the book still has the power to evoke these intense reactions means it’s still relevant and valuable.

The last passages of the book speak beautifully to this reality, directly from Russ to the book (to the reader):

Do not complain when at last you become quaint and old fashioned, when you grow as outworn as the crinolines or a generation ago and are classed with Spicy Western Stories, Elsie Dinsmore, and The Son of the Sheik; do not mutter angrily to yourself when young persons read you to hrooch and hrch and guffaw, wondering what the dickens you were all about. Do not get glum when you are no longer understood, little book. Do not curse your fate. Do not reach up from readers’ laps and punch the readers’ noses.

Rejoice, little book!

For on that day, we will be free. (213-214)

It hasn’t happened yet. I’m a young person and I’m certainly not guffawing. I was nearly in tears at parts; I ground my teeth at others.

One of the problems that seem unique to women-with-women sexuality is that it is derided as nonsexual, or nonfulfilling, or cute, or fake; any of the above. (I’m not saying that men-with-men sexuality or any other combination thereof hasn’t been derided, because it certainly has, but it’s not done in the same ways. It’s not delegitimized by calling it “not sexual, really.” If anything, the derision usually stems from an assumption of too much sexuality. But, once again, topic for another time.) This shows up early in the book, when Janet (from Whileaway, appearing in Joanna/Jeanine’s time) is on an interview show. There’s an entire set of questions with the male interviewer where he’s trying to angle without saying it that surely the women of Whileaway can’t be sexually fulfilled—he asks her why she would ban sex (aka men) from Whileaway, and she is confused. Finally, he summons up the will to say, “Of course the mothers of Whileaway love their children; nobody doubts that. And of course they have affection for each other; nobody doubts that, either. But there is more, much, much more—I am talking about sexual love.” Janet responds, “Oh! You mean copulation…. And you say we don’t have that?… How foolish of you, of course we do…. With each other, allow me to explain.” And then the program cuts her off in a panic.

Of course. After all, how often do we still hear that all a lesbian really needs is to “try out a man and she’ll see what she’s missing?” Honestly.

Janet, too, seems to be the only woman in the book with a fully realized and comfortable sexuality—though in the end, she also engages in a relationship that makes her uncomfortable, with Laura. Laura is younger than her, and that’s a taboo on Whileaway, but Laura seems to be the only other woman attracted to Janet in all the world. Janet isn’t sure what to make of the/our world’s discomfort and prudery, let alone the rude and forceful attentions of men. (The scene where she kicks the ass of a Marine at a party when he becomes overly insulting and “friendly” is rather cathartic.) The sex scene between her and Laura—Laura’s first experience with a woman—is at turns tender, erotic and humorous, as it should be. Without ever delving into explicit language, Russ makes the scene sizzle with sexuality. She describes the intensity of orgasm without having to be crude about it, and the tension, and the fluidity of it all.

How could anyone call the book “sexless” or ignore its intense, scorching sexuality? How?

The same way they always do, I suppose.

I’ll also say that there was one part of the narrative which made me uncomfortable in the not-good way: the “changed” and “half-changed” of the man’s world in Jael’s time. Yes, it’s a scathing critique of patriarchy and what men see in/use women for, what they hide in themselves. The young men are forced to take the operations, after all; it has nothing to do with choice. However—wow, can I see where that treads very, very close to transphobic territory. It doesn’t help that the attitude of second wave feminism toward transwomen was negative at best, violently hostile at worst—it doesn’t make me terribly inclined to give the benefit of the doubt. So, reader be forewarned. It’s a very short section of the book, but it’s there, and it’s got some uncomfortable tension for me as a critic/reader in 2011.

The Female Man is many things: postmodern, deconstructive, feminist, and queer, to name a few. It’s already had plenty of recognition for its feminist and narrative contributions to the field. I’d like us to remember that it is also a work of queer SFF, one of the earliest (so far as I know) to get big-award recognition and provoke a firestorm of critiques across the genre. If I can safely say one thing, it is that people knew about this book. They were reading it. I have to rely on secondary sources for that knowledge, since I wasn’t alive at the time, but as in Merrick’s book, the sources make it pretty clear: people were engaging with this book, for better or worse. We’ve seen plenty of the “worse,” but what about the “better?”

I wonder, for how many women on the brink, struggling with their sexuality, was this book a keystone? For how many did this book provide words with which to speak? I can imagine it must have been at least a few, if not more. Women who sat up nights clutching at Russ’s book with tears in their eyes, seeing yes, me, yes, me in the pages—women who found their first real representation. Not the sensual but usually sexless stories that often came before (as if women simply were not the sort of creatures who had sex with each other in stories!), but a book that showed women “doing the deed” and made it charged for female attention, not for heterosexual male titillation.

Those are the histories I’d like to hear, if they’re out there. I can only say so much. I wasn’t around when The Female Man was published; I can’t speak to what it was like to be a queer person in the 1970s. I can only imagine, and gather stories from the people who really were there.

So, if you’ve got one, or another appreciation or critique you’d like to share about this book, have at. Reclamation isn’t just about the texts; it’s also about the readers. I want to hear you.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.