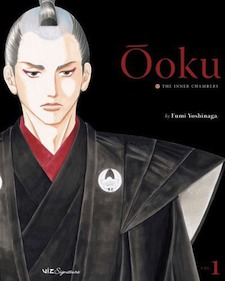

In 2009, Ooku: The Inner Chambers became the first manga to win the James Tiptree Jr. Award for a work of speculative fiction dealing with issues of gender. (It was also nominated for an Eisner Award and won the Osamu Tezuka Cultural Prize, as well as a few gender and SFF-related awards in Japan.) It is written and illustrated by Fumi Yoshinaga—who, to my surprise, I had encountered before: she wrote historically inspired yaoi comics which were published in Japanese men’s magazines, one of which I read years ago.

Ooku is set in the Edo period in Japan. It is an alternate-history tale that draws from actual figures and occurrences but re-imagines them in its unique setting: a world in which three quarters of the male population has died of a plague. This is an engaging idea on its own, but Yoshinaga goes much further in her exploration of patriarchy, gendered structures of power and masculinity than a simple “Oh, look, the men are gone!” plot.

There are things to be said about the rising position of women writers in comics and how works like Ooku: The Inner Chambers help with that re-assessment of their worth. For the time being, though, I’d like to take a closer look at the first volume in this multiple-award winning series.

Ooku is an odd read, not least because while I loved it, there were some things that really itched at the back of my mind after I’d finished the volume. It’s not often I can love the start of a comic as much as I did this one and still be grumbly about some things in it; usually the grumbly-part detracts from the love-part.

What I love is the world-building and its attention to detail. Yoshinaga actually extrapolates what would have likely happened in this situation: while roles do pass over to women, the structures of the patriarchy and its inherent misogyny remain like lingering ghosts, unexamined and unexplained. After a few generations have passed and no one living can remember a time that was different (with the exception of one elderly scribe who keeps the histories of the shogunate, as we find out at the very end of the volume), these structures are simply accepted. Yoshimune is beginning to question them at the end of the first volume: why must a woman take a man’s name when she ascends to a position of leadership? What is wrong with a woman’s name, if it is a woman doing the job and women have power? Why, despite the fact that the new Shogun is not actually virgin, is there a “secret swain” who must be murdered for taking her maidenhead and thereby “injuring” her—because admitting she isn’t a virgin is a problem? Why the continued value, as demonstrated by normal upper class folks, of chastity and virginity for a woman who may never be able to find a bridegroom? They don’t make sense, and Yoshimune knows this.

What especially bothers her is that she can see the lingering misogyny. She can see that women, despite their position in society and the fact that they hold power over men, are still viewed in a certain negative way. She, for example, is not allowed as Shogun to speak to male foreign dignitaries—it’s just “the way it is,” but she knows it’s wrong, and knows on some level it is so she isn’t revealed as a woman to the dignitaries.

This level of thought to what would change and what would stay the same is fantastic. The historical parts of the narrative—ie, keeping the names of the Shogun the same and changing their gender, the actual unrest and periods of war, the socio-economic layout—are, as far as my amateur eye can tell, accurate and well-adapted.

The characters themselves are highly developed. Yoshimune and Mizuno are both enjoyable to read about and feel like real, multifaceted people. Yoshinaga pays a great deal of attention to social backgrounds, attitude and body language in her art. The characters are always emoting in their illustrations; very few scenes are static. There is a high level of attention to background detail that helps build the historical narrative, too.

Ooku has my attention, and I’m happily going to pick up the rest of the series to see if Yoshinaga delivers on the implicit promise of her text. I hope she develops a fantastic, gender-concerned and nuanced alternate history that deals with patriarchy, power and feminism.

However! I do feel that there are points in which Ooku is lacking as of the first volume. While it does feature a strong female lead, I was disappointed by the fact that Yoshinaga makes no mention of lesbian/queer sexual dynamics for women, which are certain to have developed visibly along with the changed social structure. She does write scenes of male homoerotic tension, though there is also one near-rape scene that detracts from this as it seems to play without examination into the fetishes common to yaoi comics (such as those she has previously written) where rape is portrayed as titillating. Naturally, I find this unpleasant. The lead female character is aggressively sexual with men and bears no shame for it, which is fantastic, but she needs to do more with her women’s society. Women all seem to be heterosexual, despite the fact that some of them have taken on male roles and will never have sexual relations with a man without paying for it. The few men are the ones who are attracted to (and sometimes assault) each other. That is problematic to say the least.

On one level, it seems to deny female sexual agency in the exact way that she is trying to build it in a character like Yoshimune. The male-brothels are described as places for reproductive purposes and not really sexual satisfaction, as if the only reason women want to have sex is to have a child. If there was a developed queer aspect of the society where women found their sexual satisfaction in other women or those who have adopted a male role, this would work. As it stands, it detracts from the work Yoshinaga is trying to do with gender and displays a lack of interest or consideration for the woman as a sexual, sensual being with an inner life. The focused attention on and valuing of male eroticism while ignoring female eroticism, plus the attitude that “of course all men can be attracted to men when you put them alone together, but nevermind women being attracted to women when they’re alone together” plays into some of the sillier, more ingrained tropes of the “boy’s love” genre. I expect a higher level of examination and deconstruction from a comic as interesting and otherwise nuanced as this one.

Lest it sound like I’m down on the scenes of male sexuality, I’m absolutely not; I do love that Yoshinaga deals with some queer content. I thought one of the most touching, personal scenes in this volume was the interaction between Mizuno and the young sempster, Kakizoe, when Mizuno realizes that Kakizoe has a massive crush on him and gives the younger man a chaste kiss as a thank-you. It reveals a lot about Mizuno as a person—his kindness and in some ways his naïveté, as he had never before considered a man sexually. It’s only after he enters the Ooku that he begins to consider the potential breadth of sexuality, including his own. (It is implied that the reason he chooses not to pursue a relationship with Kakizoe is the woman he left at home who he is attempting to be faithful to.)

Also, though I understand as a writer and reader why the translator chose to go with a sort of faux-Elizabethan English, I disliked it intensely. Why, you may wonder? After all, the original text is in archaic Japanese appropriate to the time period, which was very cool of Yoshinaga. I dislike this translation because it’s not real, nuanced Elizabethan-caliber English. It’s the kind of Elizabethan English you get in Hollywood movies about Shakespeare, and I heartily do not like that. It feels cheap. I would have been double thumbs up about a true, apples-to-apples translation with all the flourishes and spellings and strangeness of that English. Or, alternately, a note that the text is originally in an archaic form that wouldn’t translate well and so modern English will be used. Not this wishy-washy, not-one-or-the-other thing. It’s not difficult to read, but it is a bit grating, especially when you see constructions that belong in modern English and the only thing the translator changed was a “thee” or “thou.” (Possibly, this is my academic nerdery peeking through. I will give the benefit of the doubt that most people will not be bothered by this little issue.)

All-together, I really enjoyed this comic, and I think that if Yoshinaga develops her text and delivers on the engaging, cool themes she’s set up, Ooku will be the best manga published in recent years. It could also expand the kind of comics that are translated and published in English and possibly help the attitude toward female comic-writers. The James Tiptree Jr. Award seems to have been well-gifted here—I can’t wait to see where Ooku: The Inner Chambers goes.