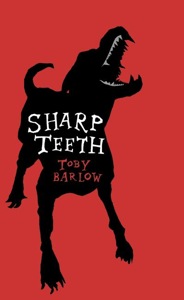

Though zombies and werewolves get a substantial amount of press here at tor.com (zombies especially), I’ve always felt that, compared to vampires, zombies and werewolves never get the love they deserve. They’re left all alone on Friday night while vampires get to go to the prom. Still, now and then, a clever author will take them out on a date to remember. Toby Barlow and S.G. Browne, in Sharp Teeth (Harper Perennial) and Breathers, respectively, show these too-often cliché-ridden creatures a good time, of sorts. Both deal with power, violence, love and the joys of eating people. In this post, I’ll look at Sharp Teeth, and in the next, at Breathers.

The story details a haphazard war of werewolf packs in LA, involving drugs, dogfights, sex, and gambling. In the middle of it all, Anthony, a well-meaning but fairly powerless dogcatcher, falls in love with the female of a pack. She (she remains unnamed in the novel) hooks up with him after her pack falls apart. The novel follows multiple points of view, various lycanthropes and the humans who inadvertently get in their way.

Sharp Teeth spares nothing in its focus on violent desires and territorialism, but before I get further into that, a word or two about its structure. Sharp Teeth is a werewolf novel written in free-verse poetry. If you’re wondering how well that works, for the most part it works brilliantly. At its weakest, there are places—sections of exposition, primarily—in which it’s not too different than strangely formatted prose. Even in those places, however, the format isn’t jarring enough to lose the narrative. The strongest parts, where the poetry really shines, are those in which Barlow delves into the juxtaposition of human nature and canine. In those sections, the dual nature of the book, as a novel and a poem, serves as a device for navigating the duality of the werewolf.

For example:

She could play in your yard, but

you would not want her

crossing your trail in the twilight.

And were you cornered by her,

eye to eye,

you would see that

there are still some watchful creatures

whose essence lies unbound by words.

There is still a wilderness.

The overall effect of Barlow’s poetry is terse and quick action befitting the title, mixed with intriguing portrayals of fear, power, submission, and alienation. I find it a welcomed alternative to wordy, ornate novels that read like The Vampire Lestat with excessive body hair.

There is one case where the poetic format is not used to full advantage, however. The motivation for the unnamed woman’s affection for Anthony was never very clear to me. They’re in love, yes, but why? How is described but not why. It just sort of happens. Fair enough; love works that way some times. But given poetry’s ability to convey intense emotion, this seemed a lost opportunity. Barlow has the skill to have made their relationship more intriguing and emotionally complex. In other characters, he weaves far richer interactions and I can’t help but wonder why he didn’t forge a stronger connection between Anthony and his unnamed beloved.

There is one case where the poetic format is not used to full advantage, however. The motivation for the unnamed woman’s affection for Anthony was never very clear to me. They’re in love, yes, but why? How is described but not why. It just sort of happens. Fair enough; love works that way some times. But given poetry’s ability to convey intense emotion, this seemed a lost opportunity. Barlow has the skill to have made their relationship more intriguing and emotionally complex. In other characters, he weaves far richer interactions and I can’t help but wonder why he didn’t forge a stronger connection between Anthony and his unnamed beloved.

Speaking of the unnamed woman, I referred to her earlier as “the female.” This is because there’s only one per pack. Barlow, in a Q-and-A at the end of the book, says that the story was born from learning that wild dog packs usually have one female each, with males fighting for her attention. I’m curious to know the reaction of women who’ve read the book. Do you feel that in patterning the were-society’s gender roles after wild dogs, Barlow created a sexist structure? Or has he exempted himself from sexism by simply re-creating what happens in nature?

My opinion? Yeah, that’s sexist. Less for the one-woman-per-pack rule than how the female characters behave. For the female werewolves in Sharp Teeth, sex is currency. It’s a means to gain favor, attention and protection. There’s little erotic or romantic fulfillment involved, except in the unnamed woman’s relationship with Anthony. As much as I enjoyed the book on other levels, I can’t say I’m too thrilled that the female characters are defined to a great extent by their reactions to men.

Far more fulfilling is the relationship between Peabody, an investigator, and Venable and Goya, a pair of criminals in the Mr. Wint and Mr. Kidd style. Though it seems Anthony and his semi-canine lover are meant to be the key protagonists, Peabody is a far more thoroughly realized character with clear motivations, stressors, and dangers to face as he enters into the bizarre werewolf-dogfight-druglord underground.

Then there’s the interaction between Lark—the former leader of the unnamed woman’s pack, who goes into hiding after being betrayed—and Bonnie, a kind but fairly witless woman who thinks he’s a regular dog. To Bonnie, he is just the bestest dog ever. She pets him and feeds him and thinks he’s swell. He likes her, likes being a cared-for dog, but when all is said and done, he’s just using her for free Alpo and an occasional scratching behind the ears, and when he no longer needs her, he jets.

Then there’s the interaction between Lark—the former leader of the unnamed woman’s pack, who goes into hiding after being betrayed—and Bonnie, a kind but fairly witless woman who thinks he’s a regular dog. To Bonnie, he is just the bestest dog ever. She pets him and feeds him and thinks he’s swell. He likes her, likes being a cared-for dog, but when all is said and done, he’s just using her for free Alpo and an occasional scratching behind the ears, and when he no longer needs her, he jets.

Poor Bonnie. On the bright side, she’s one of the few normals to make it through the story without getting disemboweled (and Lark does repay her for her kindness eventually, after a fashion). Still, nobody in Sharp Teeth goes totally unscathed. It’s a physically and emotionally violent book. And it should be, I say. What’s the point of writing about werewolves, after all, if you’re not going to get blood and guts and veins in your teeth? If you’ll forgive me for stating the obvious, the reason we read and write about monsters is to examine what’s monstrous in people. This isn’t half true of half-human monsters; it’s doubly true. Werewolves, the Incredible Hulk, Mr. Hyde, Cu Chulainn and other transformative people-beasts are in no small part a symbolic manifestation of the desire for unchecked aggression.

And even the mildest, most Bruce Banner-ish among us wishes, from time to time, to beat the ever-lovin’ chutney out of someone. Which leads me to S.G. Browne’s Breathers, incidentally. Stay tuned.