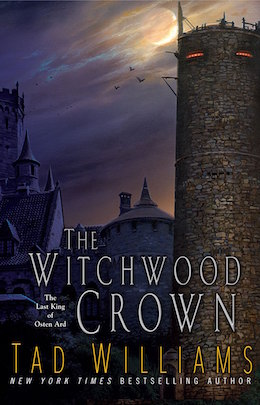

Tad Williams’ ground-breaking epic fantasy saga of Osten Ard begins an exciting new cycle with The Witchwood Crown, available June 27th from DAW.

Now, twenty-four years after the conclusion of Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn, Tad returns to his beloved universe and characters with The Witchwood Crown, the first novel in the long-awaited sequel trilogy, The Last King of Osten Ard.

Thirty years have passed since the events of the earlier novels, and the world has reached a critical turning point once again. The realm is threatened by divisive forces, even as old allies are lost, and others are lured down darker paths. Perhaps most terrifying of all, the Norns—the long-vanquished elvish foe—are stirring once again, preparing to reclaim the mortal-ruled lands that once were theirs…

Conversation With A Corpse-Giant

The waxing moon was nearly full, but curtained by thick clouds, as were the stars. It was not hard for Jarnulf to imagine that he was floating in the high darkness where only God lived, like a confessor-priest in his blind box listening all day long to the sins of mankind.

But God, he thought, did not have that corpse-smell in His nostrils every moment. Or did He? For if my Lord doesn’t like the scent of death, Jarnulf won- dered, why does He make so many dead men?

Jarnulf looked to the corpse stretched at the side of the tree-burial platform nearest the trunk. It was an old woman, or had been, her hands gnarled like tree roots by years of hard work, her body covered only by a thin blanket, as though for a summer night’s sleep instead of eternity. Her jaw was bound shut, and snow had pooled in the sockets of her eyes, giving her a look of infinite, blind blankness. Here in the far north of Rimmersgard they might worship at the altar of the new God and His son, Usires Aedon, but they honored the old gods and old ways as well: the corpse wore thick birch bark shoes, which showed she had been dressed not for a triumphal appearance in Usires the Ran- somer’s heavenly court, but for the long walk through the cold, silent Land of the Dead.

It seemed barbaric to leave a body to scavengers and the elements, but the Rimmersfolk who lived beside this ancient forest considered it as natural as the southerners setting their dead in little houses of stone or burying them in holes. But it was not the local customs that interested Jarnulf, or even what waited for the dead woman’s soul in the afterlife, but the scavengers who would come to the corpse—one sort in particular.

The wind strengthened and set clouds flowing through the black sky, the treetop swaying. The platform on which Jarnulf sat, thirty cubits above the icy ground, rocked like a small boat on rough seas. He pulled his cloak tighter and waited.

***

He heard it before he could see anything, a swish of branches out of time with the rise and fall of the wind’s noises. The scent came to him a few moments later, and although the corpse lying at the far end of the platform had an odor of its own, it seemed almost healthy to Jarnulf, matched against this new stink. He was almost grateful when the wind changed direction, although for a mo- ment it left him with no way of judging the approach of the thing he had been waiting for since the dark northern afternoon had ended.

Now he saw it, or at least part of it—a gleam of long, pale limbs in the nearby treetops. As he had hoped, it was a corpse-giant, a Hunë too small or too old to hunt successfully and thus reduced to preying on carcasses, both animal and human. The sinking moon still spread enough light to show the creature’s long legs flexing and extending as it clambered toward him through the treetops like a huge, white spider. Jarnulf took a long, deep breath and wondered again whether he would regret leaving his bow and quiver down below, but carrying them would have made the climb more difficult, and even several arrows would not kill a giant quickly enough to be much use on such a dangerously con- strained battlefield—especially when his task was not to kill the creature, but to get answers from it.

He was frightened, of course—anyone who was not a madman would be— so he said the Monk’s Night Prayer, which had been one of Father’s favorites.

Aedon to my right hand, Aedon to my left

Aedon before me, Aedon behind me

Aedon in the wind and rain that fall upon me

Aedon in the sun and moon that light my way

Aedon in every eye that beholds me and every ear that hears me Aedon in every mouth that speaks of me, in every heart that loves me Ransomer go with me where I travel

Ransomer lead me where I should go Ransomer, give me the blessing of Your presence As I give my life to You.

As Jarnulf finished his silent recitation, the pale monstrosity vanished from the nearest tree beneath the edge of the platform; a moment later he felt the entire wooden floor dip beneath him as the creature pulled itself up from below. First its hands appeared, knob-knuckled and black-clawed, each big as a serving platter, then the head, a white lump that rose until light glinted from the twin moons of its eyes. For all its fearsomeness, Jarnulf thought the monster looked like something put together hurriedly, its elbows and knees and long hairy limbs sticking out at strange angles. It moved cautiously as it pulled itself up onto the platform, the timbers barely creaking beneath its great weight. Its foxfire eyes never left the dead woman at the far end of the wooden stand.

Jarnulf had seen many giants, had even fought a few and survived, but the superstitious horror never entirely went away. The beast’s shaggy, powerful limbs were far longer than his own, but it was old and smaller than most of its kind. In fact, only the giant’s legs and arms were full-sized: its shrunken body and head seemed to dangle between them, like those of some hairy crab or long-legged insect. The Njar-Hunë’s fur was patchy, too: even by moonlight Jarnulf could see that its once snowy pelt was mottled with age.

But though the beast might be old, he reminded himself, it was still easily capable of killing even a strong man. If those grotesque, clawed hands got a grip on him they would tear him apart in an instant.

The giant was making its way across the platform toward the corpse when Jarnulf spoke, suddenly and loudly: “What do you think you are doing, night- walker? By what right do you disturb the dead?”

The monster flinched in alarm and Jarnulf saw its leg muscles bunch in preparation for sudden movement, either battle or escape. “Do not move, corpse-eater,” he warned in the Hikeda’ya tongue, wondering if it could un- derstand him, let alone reply. “I am behind you. Move too quickly for my liking and you will have my spear through your heart. But know this: if I wanted you dead, Godless creature, you would be dead already. All I want is talk.”

“You… want… talk?” The giant’s voice was nothing manlike, more like the rasping of a popinjay from the southern islands, but so deep that Jarnulf could feel it in his ribs and belly. Clearly, though, the stories had been true: some of the older Hunën could indeed use and understand words, which meant that the terrible risk he was taking had not been completely in vain.

“Yes. Turn around, monster. Face me.” Jarnulf couched the butt of his spear between two of the bound logs that formed the platform, then balanced it so the leaf-shaped spearhead pointed toward the giant’s heart like a lodestone. “I know you are thinking you might swing down and escape before I can hurt you badly. But if you do, you will never hear my bargain, and you will also likely not eat tonight. Are you by any chance hungry?”

The thing crouched in a jutting tangle of its own arms and legs like some horribly malformed beggar and stared at Jarnulf with eyes bright and baleful. The giant’s face was cracked and seamed like old leather, its skin much darker than its fur. The monster was indeed old—that was obvious in its every stiff movement, and in the pendulous swing of its belly—but the narrowed eyes and mostly unbroken fangs warned that it was still dangerous. “Hungry… ?” it growled.

Jarnulf gestured at the corpse. “Answer my questions, then you can have your meal.”

The thing looked at him with squinting mistrust. “Not… your… ?”

“This? No, this old woman is not my grandmother or my great-grandmother. I do not even know her name, but I saw her people carry her up here, and I heard them talking. I know that you and your kind have been raiding tree burials all over this part of Rimmersgard, although your own lands are leagues away in the north. The question is… why?”

The giant stared fixedly at the spear point where it stood a few yards from its hairy chest. “I tell what you want, then you kill. Not talk that way. No spear.”

Jarnulf slowly lowered the spear to the platform, setting it down well out of even the giant’s long reach, but kept his hand close to it. “There. Speak, devil- spawn. I’m waiting for you to tell me why.”

“Why what, man?” it growled.

“Why your kind are suddenly roaming in Rimmersgard again, and so far south—lands you were scourged from generations ago? What calamity has driven your evil breed down out of the Nornfells?”

The corpse-giant watched Jarnulf as carefully as it had watched the spear- point, its breath rasping in and out. “What… is… ‘calamity’?” the giant asked at last.

“Bad times. Tell me, why are you here? Why have your kind begun to hunt again in the lands of men? And why are the oldest and sickliest Hunën—like you—stealing the mortal dead for your meals? I want to know the answer. Do you understand me?”

“Understand, yes.” The thing nodded, a grotesquely alien gesture from such a beast, and screwed up its face into a puzzle of lines. “Speak your words, me— yes.” But the creature was hard to understand, its speech made beastlike by those crooked teeth, that inhuman mouth. “Why here? Hungry.” The giant let its gray tongue out and dragged it along the cracked lips, reminding Jarnulf that it would just as happily eat him as the nameless old woman whose open-air tomb this was. Even if it answered his questions, could he really allow this in- human creature to defile an Aedonite woman’s body afterwards? Would that not be a crime against Heaven almost as grave as the giant’s?

My Lord God, he prayed, grant me wisdom when the time comes. “‘Hungry’ is not answer enough, giant. Why are your kind coming all the way to Rimmers- gard to feed? What is happening back in the north?”

At last, as if it had come to a decision, the beast’s mouth stretched in what almost seemed a smile, a baring of teeth that looked more warning than wel- come. “Yes, we talk. I talk. But first say names. Me—” it thumped its chest with a massive hand—“Bur Yok Kar. Now you. Say.”

“I do not need to tell you my name, creature. If you wish to take my bar- gain, then give me what I ask. If not, well, our trading will end a different way.” He let his hand fall to the shaft of the spear where it lay beside him. The giant’s gleaming eyes flicked to the weapon, then back to his face again.

“You ask why Hojun—why giants—come here,” the creature said. “For food. Many mouths hungry now in north, in mountains. Too many mouths.”

“What do you mean, too many mouths?”

“Higdaja—you call Norns. Too many. North is awake. Hunters are… everywhere.”

“The Norns are hunting your kind? Why?”

“For fight.”

Jarnulf sat back on his heels, trying to understand. “That makes little sense. Why would the Hikeda’ya want to fight with your kind? You giants have al- ways done their bidding.”

The thing swung its head from side to side. The face was inhuman but some- thing burned in the eyes, a greater intelligence than he had first guessed. It reminded Jarnulf of an ape he had once seen, the prize of a Naarved merchant who kept it in a cage in the cold courtyard of his house. The beast’s eyes had been as human as any man’s, and to see it slumped in the corner of its too-small prison had been to feel a kind of despair. Not everything that thinks is a man, Jarnulf had realized then, and he thought it again now.

“Not fight with,” the giant rasped. “They want us fight for. Again.”

It took a moment to find the creature’s meaning. “Fight for the Norns? Fight against who?”

“Men. We will fight men.” It showed its teeth. “Your kind.”

It was not possible. It could not be true. “What are you talking about? The Hikeda’ya do not have the strength to fight mortals again. They lost almost everything in the Storm King’s War, and there are scarcely any of them left. All that is over.”

“Nothing over. Never over.” The giant wasn’t looking at him, though, but was staring raptly at the body of the old woman. Thinking again about supper.

“I don’t believe you,” said Jarnulf.

Bur Yok Kar turned toward him, and he thought he could see something almost like amusement in the ugly, leathery face. The idea of where he was, what he was doing, and how mad it was, suddenly struck Jarnulf and set his heart racing. “Believe, not believe, not matter,” the corpse-giant told him. “All of north world wakes up. They are everywhere, the Higdaja, the white ones. They are all awake again, and hungry for war. Because she is awake.”

“She?”

“Queen with the silver face. Awake again.”

“No. The queen of the Norns? No, that cannot be.” For a moment Jarnulf

felt as though God Himself had leaned down from the heavens and slapped him. In an instant, everything that Father had taught him—all his long-held certainties—were flung into confusion. “You are lying to me, animal.” He was desperate to believe it was so. “Everyone knows the queen of the Norns has been in a deathly sleep since the Storm King fell. Thirty years and more! She will never awaken again.”

The giant slowly rose from its crouch, a new light in its eyes. “Bur Yok Kar not lie.” The beast had recognized Jarnulf’s momentary loss of attention, and even as he realized it himself, the giant took a step toward him. Although half the length of the treetop platform still separated them, the creature set one of its huge, knobbed feet on the head of his spear, pinning it flat against the teth- ered logs. “Ask again. What name you, little man?”

Angry and more than a little alarmed at his own miscalculation, Jarnulf rose and took a slow step backward, closer to the edge of the platform. He shifted his balance to his back foot. “Name? I have many. Some call me the White Hand.”

“White Hand?” The giant took another shuffling step toward him, still keeping the spear pinned. “No! In North we hear of White Hand. Big warrior, great killer—not skinny like you.” The creature made a huffing noise, a kind of grunt; Jarnulf thought it might be a laugh. “See! You put spear down. Hunter, warrior, never put spear down.” The giant was near enough now that he could smell the stench of the rotting human flesh in its nails and teeth, as well as the odor of the beast itself, a sour tang so fierce it cut through even the stiff, cold wind. “Ate young ones like you before.” The corpse-giant was grinning now, its eyes mere slits as it contemplated the pleasure of a live meal. “Soft. Meat come off bones easy.”

“I am finished with you, Godless one. I have learned what I needed to know.” But in truth Jarnulf now wanted only to escape, to go somewhere and try to make sense of what the creature had told him. The Norn Queen awake? The Norns preparing for war? Such things simply could not be.

“You finish? With me?” The huff of amusement again, followed by the car- rion stench. Even as the giant leaned toward him its head still loomed high above Jarnulf’s, and he was now within reach of those long, long arms as well. This monster might be old, might have to scavenge its meals from burial plat- forms, but it still weighed perhaps three times what he did and had him trapped in a high, small place. Jarnulf took one last step back, feeling with his heel for the edge of the platform. Beyond that was only a long drop through sharp branches to the stony ground.

Not even enough snow to break my fall, he thought. Lord, O Lord, make my arm strong and my heart steadfast in Your name and the name of Your son, Usires the Aedon. As if reminded of the cold, he adjusted his heavy cloak. The giant paid no at- tention to this small, insignificant movement; instead, the great, leering head bent even closer until it was level with his own. Jarnulf had nowhere to retreat and the corpse-giant knew it. It reached out a massive hand and laid it against the side of Jarnulf’s face in a grotesque parody of tenderness. The fingers curled, each as wide as the shaft of the spear that was now so far out of his reach, but Jarnulf ducked beneath its grasp before it caught at his hair and twisted his head off. Again they stood face to face, man and giant.

“White Hand, you say.” With Jarnulf’s spear pinned to the platform beneath its foot, the beast was in no hurry. “Why they call you that, little Rimmers- man?”

“You will not understand—not for a little while, yet. And I was not born in Rimmersgard at all, but in Nakkiga itself.”

The cracked lips curled. “You not Higdaja, you just man. You think Bur Yok Kar stupid?”

“Your problem is not that you are stupid,” Jarnulf said. “Your problem is that you are already dead.” Jarnulf looked down. A moment later the giant looked down too. Beyond the hilt in Jarnulf’s hand a few inches of silvery blade caught the starlight. The rest of it was already lodged deep in the monster’s stomach. “It is very long, this knife,” Jarnulf explained as the giant’s jaw sagged open. “Long enough that the blood does not stain me, which is why I carry the name White Hand. But my knife is also silent, and sharp as the wind—oh, and cold. Do you feel the cold yet?” With a movement so swift the giant had no time to do more than blink, Jarnulf grabbed the hilt with both hands and yanked upward, dragging the blade from the creature’s waist to the bottom of its ribcage, twisting it as he cut. The great beast let out a howl of astonishment and pain and clapped its huge hands over the wound even as Jarnulf threw himself past it, still hold- ing fast to the hilt of his long knife. As he tumbled into the center of the plat- form the blade slid back out of the beast’s hairy stomach, freeing a slide of guts and blood. The monster howled once more, then lifted dripping hands to the distant stars as if to fault them for letting such a thing happen. By the time it came staggering toward him, innards dangling, Jarnulf had regained his spear.

He had no time to turn the long shaft around, so he grabbed it and charged. He rammed the rounded butt-end of the shaft into the bloody hole in the gi- ant’s midsection, freeing a bellow of agony from the creature that nearly deafened him. The logs beneath them bounced and swayed, and snow pattered down from the laden branches above as the giant thrashed and howled and plucked at the spear-shaft, but Jarnulf crouched low and braced himself, then began to push forward, hunched over the spear as its butt-end dug deep into the monster’s vitals.

The corpse-giant staggered backward, arms swinging like windmill vanes, mouth a hole that seemed too big for its head, then it suddenly vanished over the side of the tree-burial platform. Jarnulf heard it crashing through the branches as it fell, then a heavy thump as it hit the ground, followed by silence.

Jarnulf leaned out, keeping a strong grasp on the edge of the platform. His head felt light and his muscles were all quivering. The giant lay sprawled at the bottom of the tree in a tangle of overlong limbs. Jarnulf could not make out all of it through the intervening branches, but saw a pool of blackness beneath it spreading into the mounded snow.

Careless, he berated himself. And it almost cost me my life. God cannot be proud of me for that. But what the thing said had startled him badly.

Might the giant have lied? But why? The monster would have no reason to do so. The Silver Queen was awake, it had said, and so the North was coming awake as well. That certainly explained the giants now pushing down into Rimmersgard, as well as rumors Jarnulf had heard of Hikeda’ya warriors being spotted in places where they had not been seen for years. Certainly the border was as active as he had ever known it, with Nakkiga troops and their scouts everywhere. But if the giant had actually spoken the truth, it meant that Jarnulf had been wrong about many important things. He had stepped onto a bridge he thought safe only to find it cracking beneath him when it was far too late to turn back.

So Father’s murderer is not gone—not lost in the dream lands and as good as dead, but alive and planning for war again. That means everything I have done, the lives I have taken, the terror I have tried to spread among the Hikeda’ya… has all been pointless. The monster is awake.

Until this moment Jarnulf had believed he was God’s avenger—not just God’s, but Father’s as well. Now he had been proved a fool.

He watched from the platform until he was quite sure the giant was dead and his own limbs had stopped trembling, then he tossed his spear over the side and began to climb down. The wind was strengthening, bringing snow out of the north; by the time he reached the ground Jarnulf was dusted in white. He cleaned the blood and offal from his spear, then used his long, achingly sharp knife to cut off the giant’s head. He set the monster’s head in the crotch of a wide branch near the base of the burial tree, the eyes lifelessly black and stretched wide in their last surprise, the fanged mouth gaping foolishly. He hoped it would serve as a warning to others of its kind to stay away from human settlements, to find some easier forage than the corpses of Rimmersfolk, but just now defending the bodies of dead men and women was not what domi- nated his thoughts.

“We men beat back the witch-queen and defeated her.” He spoke only to himself, and so quietly that no other creature heard him, not a bird, not a squir- rel. “If she has truly returned, this time men like me will destroy her.” But Jarnulf had made promises to himself and God before, and those pledges had now been proved nothing but air.

No, save your words for fitter things, he told himself. Like prayer.

Jarnulf the White Hand tipped the long spear across his shoulder and began walking back to the part of the snowy woods where he had left his horse.

Excerpted from The Witchwood Crown, copyright © 2017 by Tad Williams.