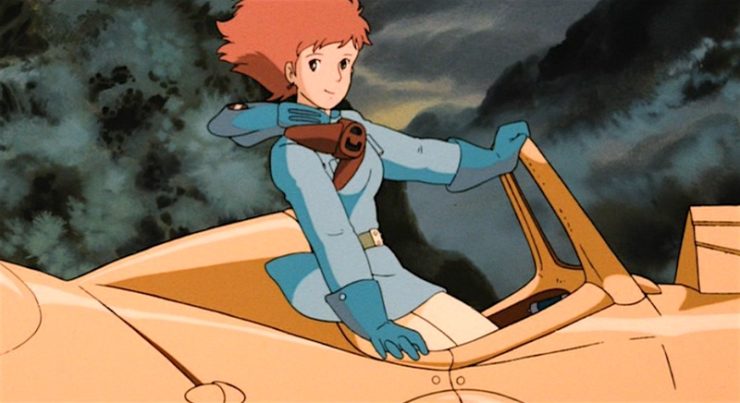

Over 30 years ago—in March of 1984—Hayao Miyazaki’s first original movie soared into theaters. This was Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, and it proved a watershed moment in the history of anime. Here was a film built around real thematic concerns, with a heroine who fronted an action movie without becoming an action cliché. Here monsters were revealed to be good, and humans were revealed to be… complicated. Here, Miyazaki created a film that would serve as a template for the rest of his career.

And maybe best of all, Nausicaä’s success led to the foundation of Studio Ghibli the following year.

Creating the Valley

Toshio Suzuki, editor of the magazine Animage, was impressed by Miyazaki’s work on The Castle of Cagliostro. He asked Miyazaki to pitch ideas to Animage’s publisher, Tokuma Shoten, but when his film ideas were turned down, Tokuma asked him to do a manga.

Miyazaki began writing and drawing Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind in his spare time in 1982, in addition to his work directing TV shows (including a few more episodes of Lupin the III) and the manga soon became Animage’s most popular story. Hideo Ogata and Yasuyoshi Tokuma, the founders of Animage, joined Tokuma Shoten in asking Miyazaki for a film adaptation, which he finally agreed to do if he could direct. Isao Takahata came on as a producer, but they needed to choose an animation studio. They went with a studio called Topcraft, hired animators for Nausicaä only, and paid them per frame.

The animators managed to create an iconic work in only 9 months, with what would be a $1 million budget today.

This was Miyazaki’s first collaboration with Joe Hisaishi, a minimalist composer who would go on to score all of Miyazaki’s films, as well as other anime productions, and many of the films of Beat Takeshi Kitano. (Joe Hisaishi actually based his stage name on Quincy Jones – since in Japanese his name would be written Hisaishi Joe, with “Hisaishi” using the same kanji as “Kuishi”, which is close to Quincy.)

Miyazaki’s Nausicaä (the character) is named for a character in The Odyssey, the daughter of Alcinous and Arete, who help Odysseus return home to Ithaca after his adventures. Nausicaä (the movie) was inspired by the tragedy of Minamata Bay. During the 1950s and 60s, Chisso Corporation’s chemical factory continuously dumped methylmercury into Minamata Bay. This resulted in severe mercury poisoning in people, dogs, cats, pigs, and obviously fish and shellfish, and the effects were named “Minamata Disease.” Even after it seemed the original outbreak had been resolved, Congenital Minamata Disease began cropping up in children over the next decade. There were thousands of victims over the years, and by 2004, Chisso Corporation had been forced to pay $86 million in compensation. This horrific incident inspired a great deal of activism and art, including this iconic photograph by W. Eugene Smith.

Obviously, that work focused on the victims, and the negative aspects of the environmental impact. Miyazaki took it in a different direction by exploring an environment that adapted to the poison. Much like the Japanese kaiju films of the post-World War II era that used silly rubber suits to comment on the horrors of nuclear weaponry, Miyazaki used manga, and later anime—both seen as frivolous entertainment—to comment on the destruction of the natural world.

The interesting thing to me is that Miyazaki took a horrific injustice that is know throughout Japan, and chose to look past the immediate tragedy. He commented that his imagination sparked because, since no one would fish in the Minamata Bay anymore, sea life there had exploded. He became interested in the way Nature was adapting to the poisons that had been dumped into the bay, and rather than retelling the story of the human horror, he focused on the way nature synthesized the poison and bounced back. He created an entire world that had been poisoned so he could look at the way humans’ toxicity warped the Earth, and the way the Earth healed itself.

Story

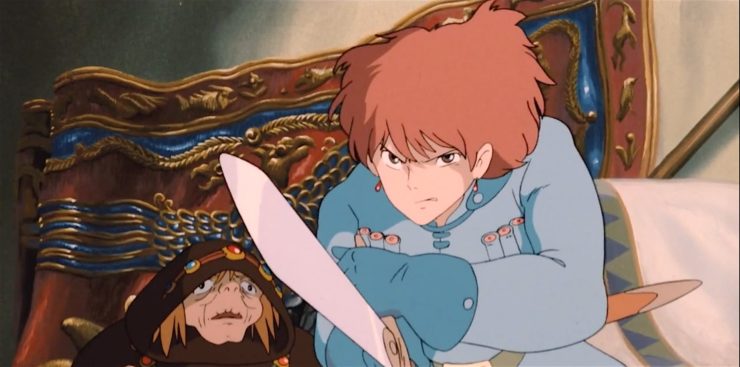

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind takes a sliver of the manga and runs with it. Nausicaä is the Princess of the Valley of the Wind. The Valley is one of the only fertile areas we see in the film, but its close proximity to the Acid Lake and the Sea of Decay put it in constant danger. Spores from the Sea of Decay—a massive toxic forest—would destroy the crops, but usually the winds keep them at bay. Life in the Valley is peaceful, but there are dark undercurrents: Nausicaä’s father is wasting away from his years of exposure to toxins, and there are rumors of war surrounding the Valley. In addition to human danger, there are massive insects called Ohm that will kill people who get too close to their young—in the film’s first action sequence, Nausicaä rescues her friend, Lord Yupa, from a pissed off Ohmu.

Life in the Valley is shattered when a massive plane carrying the Princess Lastel of the Pejite people crashes near the village. The people haven’t even finished burying the dead (including the Princess) when the warlike Tolmekians show up. They are led by another Princess, Kushana, who has to use mechanical legs and an arm after being maimed in an insect attack. Her men kill Nausicaä’s father, subjugate the people of the Valley, and claim that the Pejite cargo, a massive bioweapon called a God Warrior, will be finished in the Valley and used to destroy the Ohmu.

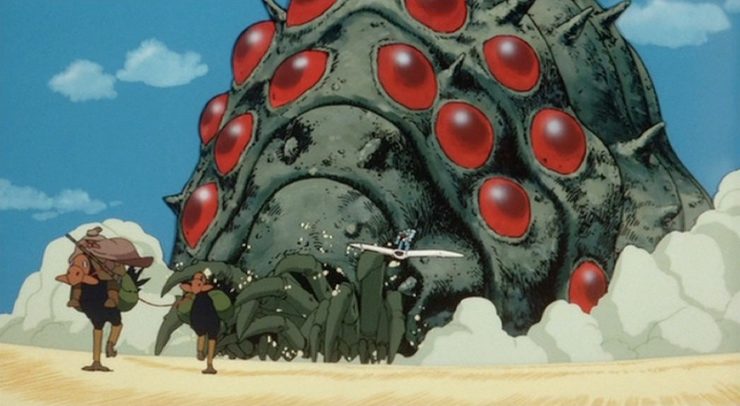

Nausicaä is caught between wanting to protect her people and save the Ohmu, especially after she discovers that there’s more to them than most people think. The Tolmekians take her hostage, the Pejite attack, and she gains an unlikely ally in Lastel’s brother, Asbel. All the conflicts come to a head when Lord Yupa, Asbel, the Pejite people, the Tolmekians, and Valley people face an army of Ohmu who are enraged when a gang of Pejites kidnap and torture one of their young.

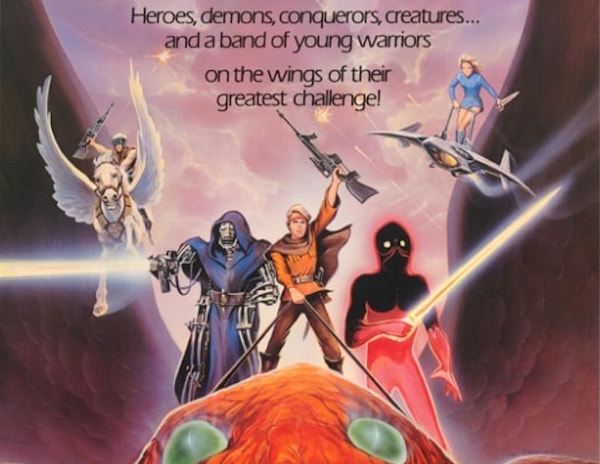

Warriors of the Wind

In 1985, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind came to America. But because we can’t have nice things, New World Pictures (Roger Corman’s production/distribution company, which, to be fair, at least gave us Heathers) were the ones who brought it over. Thinking Americans couldn’t handle a complex environmental fable, they chopped Nausicaä to bits and re-edited the film to turn the Ohmu into exactly the “relentless killing machine” cliché that Miyazaki was subverting. They deleted over 20 minutes of footage, including the introduction to the Sea of Decay, Nausicaä’s secret garden—which explains that there is pure water beneath the earth—and Nausicaä and Asbel’s journey beneath the Sea of Decay—which reveals that the plants are filtering the poison from the world, and that the Ohmu are guarding it. It also cut Nausicaä’s role down in general, and, as you can see in above, slapped a bunch of nameless male “protagonists” into the promotional art.

This utter mangling of a heartfelt piece of art led to Studio Ghibli’s “no cuts” policy going forward, which is why it took a while for many of their films to come to the U.S. (According to rumor, when the Weinsteins planned to edit Princess Mononoke, an unnamed Ghibli producer sent them a katana along with a note reading: “No Cuts.” I desperately hope this is true, and that that producer got a raise.) It wasn’t until John Lasseter was in a position of power with Disney that he and Ghibli brokered a distribution deal for their films.

Nausicaä’s Legacy

The most obvious legacy of Nausicaä is that soon after this film’s success, Studio Ghibli was born. After twenty years of work together, Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata teamed up with producer Toshio Suzuki and Yasuyoshi Tokuma of Tokuma Shoten Publishing to create a new studio with its own personality and ethos.

One of my favorite bits of trivia that I learned during this rewatch is that Hideaki Anno was the main animator on the “God Warrior” sequence (above). Anno went on to create the iconic Neon Genesis Evangelion, which is also about giant human/mechanical hybrids created to defend earth from monsters. He also did a live-action take on the God Warrior sequence for the Ghibli Museum which you can watch here. And over thirty years later, Miyazaki asked Anno to voice the main character in The Wind Rises.

Another fun thing that Nausicaä contributed to the culture: the giant, ostrich-like Horseclaws are riding birds based on the long-extinct Gastornis. These affectionate creatures supposedly inspired Final Fantasy’s beloved Chocobo.

Who Run the (Post-Apocalyptic) World?

Miyazaki—in his first original film—populates the world with complex women in order to subvert the message of a centuries-old folktale. Along with the tragedy of Minamata Bay, the 12th-century Japanese tale “The Princess (or Lady) who Loved Insects” is often cited as an influence for Nausicaä. This story is about a Heian-era girl who loves playing with bugs. This is sweet at first, but as she gets older her family and the other women of the court become increasingly critical of her. She refuses to wear makeup, to blacken her teeth, to enter into the usual court intrigues, and most problematic, she has no interest in being courted. But this doesn’t seem to be a cute story about an oddball who finds happiness with her insect friends—instead it seems much more like a didactic folktale, reminding women that their value lies in beauty and conformity.

Miyazaki takes that seed and grows a beautifully unique tree. Nausicaä does what she wants, not because she’s a spoiled princess, but because she is truly interested in learning more about the Sea of Decay.

When she finds Ohmu shells she shares them with the villagers. She treats all the people of the village as her equals. She helps fix windmills, she plays with the kids, and you get the sense that Lord Yupa is not the first hapless traveler she’s rescued from an Ohmu. Her interest in the Toxic Jungle, which could be an eccentricity in a lesser story, becomes the source of hope for her people when she realizes that the Earth is healing itself.

Best of all, it’s not just her. As enraging as Princess Kushana’s behavior is, she’s not a cardboard villain. Even after surviving an insect attack, she willing to listen to the Valley’s Wise Woman, Obaba, and to Nausicaä; Kushana isn’t subjugating the Valley of the Wind to be cruel. Obaba herself is afforded complete respect from everyone. The women of the village work just as hard as the men, and hope for their daughters to be strong like Nausicaä. Best of all, when Nausicaä is imprisoned by the Pejite, it’s the other women who rescue her. Asbel tells the women the truth, but they’re the ones who work out an escape plan and choose to substitute one of their own to dupe the guards. Lastel’s mother leads Nausicaä through a room of women who all wish her well and encourage her to save her people—a network of people considered too unimportant to be closely watched, who save the person who saves the world.

Redefining the Monstrous

Nausicaä is a post-apocalyptic adventure tale that subverts every cliché it finds. The obvious would have been to pit Nausicaä against a man: the empathetic, caring woman fights an angry, warlike man through the power of love. But Miyazaki sidesteps that trope by creating a complex female antagonist. Kushana is much more assertive than Nausicaä, but she was also maimed in an insect attack, and understandably does not see the Ohmu as anything to make peace with, and she genuinely wants to unite the people of the world in order to reclaim Earth from the insects. In a different story, she’d be the hero. Most interesting, even after she has subjugated the people of the Valley, she still wants to sit down and discuss Nausicaä’s theories about the Sea of Decay and the Ohmu’s role in the world.

But Miyazaki has an even bigger subversion in store. Nausicaä appears to be building up to a final confrontation between several different furious worldviews. The Tolmekians, the Pejite, and the Valley people are all coming together to a battlefield beside acid lake, while the Ohmu charge toward them. Kushana has her God Warrior, the Pejite have a gunship, the Valley people are waiting in hope that Nausicaä is coming back to lead them.

But that isn’t what happens.

When Nausicaä sees that the Pejite people are torturing a baby Ohmu to incite an insect stampede, she leaves her people and veers across the Acid Lake to rescue the baby. She literally sidesteps the battle, and changes the meaning of the film. This is not a war story. It is not a clash of civilizations. It’s a film about listening to Nature and redefining the monstrous. The people who tortured the baby Ohmu are monstrous. The people who would revive the God Warrior are monstrous. And rather than engaging in a dialogue with them, Nausicaä resets her priorities and goes to do the thing only she can do: save the baby Ohmu, and calm the insect herd.

When the film starts, we see an intricately designed tapestry that seems to tell a prophecy. We see a man investigating a village destroyed by poison. We get long panning shots showing us the weird beauty of the post-apocalyptic terrain. And then? We meet our heroine Nausicaä, who wanders through the forest unafraid, rejoices when she finds an intact Ohmu shell (her villagers can use the shell for all sorts of things) and pries one of its eye lenses up.

The first action we see our heroine take is to literally look at the world through the eye of a creature that most would call a monster. This is an extraordinary sequence, and Miyazaki allows it to play out with the confidence of a much more mature filmmaker. After all, this was only his second film, and his first original one, but he allows minutes to go by as Nausicaä lays on top of the shell and gazes at the forest.

It tells us almost everything we need to know about her in a few gorgeous images.

As we begin the film, we think of the insects as monsters, giants who can be blinded by rage. But they are protectors: they protect the “Sea of Decay” because beneath the poisoned forest the Earth is healing itself. All the insects can be reasoned with, all of them are sentient. Here Nausicaä is set apart from other people because of her immediate acceptance of other creatures. Rather than seeing a divide between human and animal, royal or peasant, she simply treats everyone the same. She loves the Ohmu long before she has any idea that they’re helping the forest. And of course, we get an early hint that they see her, too:

The movie presents the first Ohmu we see as a terrifying rage monster, and when Nausicaä hears gunshots and rushes to help, we assume she’s going to help the human, but no—she immediately assesses the Ohmu’s anger, decides that the human must have threatened its young, and takes action to calm the Ohmu down and lead him back into the forest, where he’ll be safe.

At the end of the film, when she rescues a baby Ohmu, she calls him a “good child” – which the subtitles on the DVD, and the dub of Warriors of the Wind changed to “good boy”. Now, while the phrase “good boy” has become a great honorific on the internet as memes praising doggos and puppers have proliferated, Miyazaki scholar Eriko Ogihara-Schuck pointed out in Miyazaki’s Animism Abroad that this is placing the Ohmu in the role of a domesticated animal, a role of servitude, where the film clearly does not see the Ohmu that way, and obviously Nausicaä referring to the Ohmu as a child puts the insect on a much more intimate standing with her.

Nausicaä doesn’t care about the differences between humans, animals, insects, plants – they are all living creatures deserving of respect. Nausicaä is also considered especially gifted when it comes to wind, but here again, it’s because she listens. There’s nothing that special about her otherwise, she’s just willing to watch the wind and go where it takes her.

But there’s another aspect that’s important to mention.

She has to choose between her own animal anger and her instinct to act out of love and trust. When the Tolmekian soldiers murder her father, her rage is entirely justified, and it is darkly satisfying to watch her burst into the room and cut them all down. But at the same time, her rage would have led to the slaughter of her people; as it is, she injures Lord Yupa when he tries to stop her.

This moment is echoed years later in Princess Mononoke, when Ashitaka steps between San and Lady Eboshi—here again people must learn to transcend violence.

The last third of the film sees Nausicaä desperately trying to get home, to warn the villagers of the oncoming Ohmu attack. As soon as she sees that a baby Ohm is being tortured she changes tracks. She knows that Yupa and Mito can warn the village—but she’s the only one who can rescue the Ohm, and hopefully accomplish the much larger task of calming the herd of insects. Yupa, with all of his nobility and swordsman’s skill, is useless here. Asbel, who would be the hero in most adventure films, is now little more than a sidekick. Not even the wise old woman Obaba has cultivated the connection to the natural world that Nausicaä has. So she grabs her glider and veers left, racing to reach the Ohm. The Ohm is being flown by two men in a basket, who are guarding their captive with a machine gun. First they shoot at Nausicaä, then they mistake her for the dead princess Lastel.

She stands on her glider, either to startle them, or in the hope that they won’t shoot when they see she’s unarmed. But once they crash, Nausicaä will do what is necessary. She is no cute moe, like Clarisse in Cagliostro, or Kiki in Kiki’s Delivery Service. But nor is she a feral child like San, or a cold bitch like Kushana and Lady Eboshi. This is a woman who ignores the pain from two gunshot wounds to help the baby Ohm.

This is a woman who unhesitatingly threatens the Ohm’s captors with a machine gun to set it free.

I have no doubt that she would have shot both of them for the chance to calm the Ohmu herd, and she would have felt terrible pain doing it, but she’s going to do what’s necessary for the good of her villagers, and the good of the Ohmu. She knows now that the Ohm are part of a larger design to save the world, and she’s not going to stop until they’re safe.

And naturally, it is this baby Ohmu, whom Nausicaä accepts as a child like any other, who saves her life during the stampede:

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind could have been a rote post-apocalyptic tale. Instead, Miyazaki created a film that is alive with ideas. The film merges a real-life tragedy with a centuries-old folktale to tell a subversive story of independence, intellectual curiosity, and, most of all, hard-won, life-saving empathy. Nausicaä created the road map for Studio Ghibli to follow, and soon Nausicaä and Asbel were joined by an army of smart girls and thoughtful boys, along with even more subversive monsters.

Leah Schnelbach wants an Ohmu of her very own! Come talk to her about post-apocalyptic super bugs on Twitter.