I was born in the swinging sixties. Australian, but brought up on a steady British diet of Enid Blyton, Swallows and Amazons, Joan Aiken and Narnia; stories featuring plucky young kids banding together and fighting the just fight. Stories in which goodness generally prevailed.

Leaning towards science fiction early on, fall-of-civilization scenarios compelled me like no other. The basic concept seemed romantic and intriguing: our world becomes a wild frontier with the old rules wiped away. A broken, silent, boundary-free world held so much more appeal than the grind of nine to five, where people intentionally dressed alike and willingly traded adventures for appointments.

John Christopher’s Tripods series (1967-68) was a particular favorite of mine—kids fighting back again alien invasion and resultant thought suppression via implant. Also Peter Dickenson’s The Changes, in which a nightmare ridden junkie wizard sleeping deep beneath a mountain made people—especially adults—shun technology.

But invading aliens and disgruntled wizards provide undeniable carte blanche. They make us honor-bound to fight for the future. Humanity must unflinchingly prevail, because, humanity is humanity, which goes hand-in-hand with hope for the future—doesn’t it? Star Trek certainly seemed to think so, but as I got a little older civilization’s crumblings got darker: John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids, and The Day of the Triffids. Some nasty stuff in both those books, but at least the heroes were fighting the good fight. The Long Tomorrow… A Canticle for Leibowitz and I began to wonder… perhaps post-disaster scenarios were not so much about wiping rules away but about imposing new ones. But before I could ponder his line of thought much further, I stumbled headlong into The Death of Grass, published a decade before the Tripods trilogy.

The Death of Grass was the book that shattered my preconceived notions of human hope and goodness as default in literature.

The Death of Grass centers around two brothers, John and David Custance. David inherits their grandfather’s farm nestled in a defendable northern valley. John is enjoying his comfortable London life when news of the devastating Chung-Li virus starts filtering from China. Chung-Li wipes out all graminaceous crops: grasses including rice, wheat and maize.

John and his civil service chum Roger watch food riots on TV; the virus has proved unstoppable, people are undisciplined with the sustenance they have, food imports have dried up, the British army is moving into position to drop bombs on cities to cull the excess population devastated farmlands will no longer be able to feed.

John, Roger and their families decide to make a run for it, heading to David’s well-fortified farm. All they care about is saving themselves.

What shocked me was not the violence that ensues, but the ease with which two families give in and take the easiest way out. They don’t bother waiting for society to fall—they actively lead the way.

How does that saying go… that civilization is only three square meals away from anarchy? These protagonists aren’t even three meals removed. They don’t get pushed to the limits of endurance, they willingly start off at that limit’s fringe. They murder soldiers, and kill a family in cold blood: the easiest way to claim their food supplies. When John’s wife Ann and their daughter Mary are raped, it’s accepted that this is the way of things now.

Not even two days passed and John is accepting of all of this. Two days during which centuries of civilization get stripped away, the Imperial British 19th century sense of moral superiority is thoroughly debunked, women are reduced to chattels and feudalism is reseeded. Two days is all it takes for humans to devolve from masters of agriculture into useless parasitic infections.

This time around, humanity requires no deity to throw it out of Eden. The garden does the job all by itself.

The Death of Grass was published over a decade before James Lovelock’s Gaia Hypothesis that likened Earth’s biosphere to a vast, self-regulating organism. The Death of Grass was not the first SF story to reveal contempt for humanity as an uncheckable, invasive species—nor is it the most violent. Post-apocalypse literature runs on a spectrum, ranging from the utopian and elegiac, through cozy catastrophe and all the way to cannibalistic nihilism. Fans of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road or TV’s The Walking Dead might possibly wonder what all the fuss is about.

The Death of Grass was published over a decade before James Lovelock’s Gaia Hypothesis that likened Earth’s biosphere to a vast, self-regulating organism. The Death of Grass was not the first SF story to reveal contempt for humanity as an uncheckable, invasive species—nor is it the most violent. Post-apocalypse literature runs on a spectrum, ranging from the utopian and elegiac, through cozy catastrophe and all the way to cannibalistic nihilism. Fans of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road or TV’s The Walking Dead might possibly wonder what all the fuss is about.

Yet, The Death of Grass showed me that the planet itself might not sit still and take the harm we throw at it. It highlighted the blind, conceited arrogance behind the belief in nature existing solely for our support and benefit. It showed me that civilization is less cemented, less durable and resilient than a child of the sixties ever wanted to believe.

The Death of Grass slots snugly into the subgenre known as Ecocatastrophe, whose authors deliver the not-too-subtle message that humanity will get no better than it deserves. We cannot negotiate our way out of it through piety or allegiance. Good people die as easily as bad. In The Death of Grass, John Custance and his people get where they want to go, but they pay a terrible price for their success (no spoilers). And it’s hard to imagine there will be many winners in that novel’s barren, grassless future.

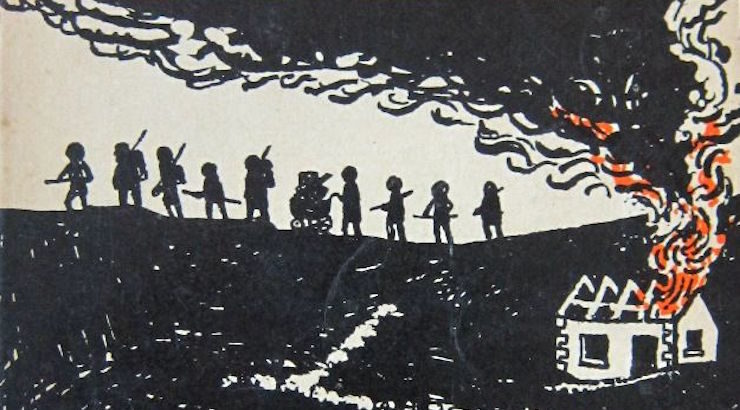

Top image: The Death of Grass cover design by John Griffiths (Penguin Books, 1963)

Cat Sparks is a multi-award-winning Australian author, editor and artist whose former employment has included: media monitor, political and archaeological photographer, graphic designer, Fiction Editor of Cosmos Magazine and Manager of Agog! Press. A 2012 Australia Council grant sent her to Florida to participate in Margaret Atwood’s The Time Machine Doorway workshop. She’s currently finishing a PhD in climate change fiction. Lotus Blue is her debut novel.

Cat Sparks is a multi-award-winning Australian author, editor and artist whose former employment has included: media monitor, political and archaeological photographer, graphic designer, Fiction Editor of Cosmos Magazine and Manager of Agog! Press. A 2012 Australia Council grant sent her to Florida to participate in Margaret Atwood’s The Time Machine Doorway workshop. She’s currently finishing a PhD in climate change fiction. Lotus Blue is her debut novel.