A dress the color of ripeness, of warning, of danger, of invitation. It’s cut in a way that beckons the eye, but it skims the edge of probability—how can it stay up? What kind of woman is comfortable wearing that?

What kind of woman, indeed?

The red dress is a staple of costuming. It communicates a thousand ideas at once. It draws the eye instantly — the primate brain in the skull of every viewer knows to watch for that color. It’s the color of a toadstool, the color of a berry, the rings on the coral snake and the best apple on the tree all at once. It’s tempting and alarming. “Stop,” it says, but also, “reach for me.” The canny costumer will use the red dress to alert the audience: look here.

But the red dress isn’t just a costume; it’s an archetype. When we see the red dress, we already have an idea of what we can expect from the woman inside of it.

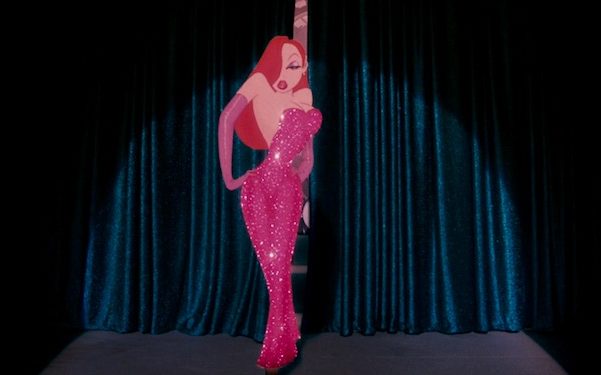

She’s not bad; she’s just drawn that way.

It’s sexy. There’s no way around that. It’s a sexy piece. It’s form-fitting, and it’s daringly cut—sometimes so daring that it feels outright dangerous. Sometimes so daring that it’s not even flattering.

Consider Number Six from Battlestar Galactica. Her iconic red dress is stunning, architectural, sexy as all get-out, and… not terribly flattering. The bodice is cut so low as to create a sense of both suspense and confusion—it seems to not quite fit, to stay put via some technology that is beyond human comprehension. There are oddly-placed seams and cutouts that don’t quite make sense, and spaghetti straps that are not only superfluous but which, when viewed from the front, don’t appear to connect to the bodice at all. The sum of these parts is a dress that insists upon its own sensuality and upon its own architectural complexity.

In this way, the red dress is a perfect preview of the wearer.

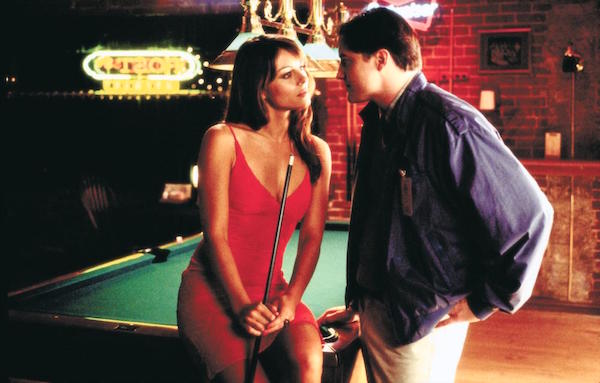

The viewer knows not to trust the woman in the red dress. The moment we see her, we know that she must be up to something. Why?

It’s the sexiness of the dress. Like the flourish of a magician’s brightest scarf, the sexiness is a blatant grab for attention. A lifetime of patriarchal indoctrination has impacted most of us thoroughly enough that we immediately distrust a woman who requests attention—especially one who requests attention using her sexuality. We’ve been taught over and over again that women who use their bodies to make money or to garner fame are morally bankrupt. We see the woman in the red dress and think: I’m being tricked.

And because the red dress is a tool drawing upon tropes that we as an audience know and love, we’re usually right. This is the part where the red dress becomes a perfect tool for a fourth-wave feminist narrative of female agency: it is a trick. It’s a simultaneous reinforcement of and a strategic use of the societal narrative of female sexuality as devilry. The woman in the red dress wears that dress because she knows that it will draw in her target, and the costumer uses the red dress because they know that it will alert the audience to the character’s moral complexity.

Because she is morally complex. She’s doing bad things, but she’s doing them for the right reasons. Or, she’s doing them for the wrong reasons, but she doesn’t care that they’re the wrong reasons because they’re her reasons. The woman in the red dress almost always has her own motives, her own goals and dreams. She is usually tied to a man, but the audience can see her chafing at that man’s ineptitude and at her own objectification at his hands. The red dress is usually ill-fitting, and that’s no accident: it is, after all, a costume.

Here is the part where the red dress becomes one of the most reliable cards in a costumer’s hand. It’s incredibly meta: it’s a costume for the actor and a costume for the character. A costumer will select the red dress because of what it says to the audience; the character will select the red dress because of what it says to her fellow characters. She is an actress in a play-within-a-play, and her part is that of the sexpot.

But the woman inside of the red dress always has an ulterior motive. She will invariably reveal them in a scene that is meant to shock, but which instead tends to satisfy. She draws a snub-nosed revolver that had been tucked into her garter, or she slams her target against a wall in a choke-hold, or she leads him into an ambush. This is set up as a betrayal—but upon analysis, it becomes obvious that the woman in the red dress rarely makes promises to the men who she betrays. The promise is made by the dress itself: she lets her costume do the talking, and the man she leads to his doom always seems to listen. He follows her into the ambush, or he gives her the access codes to the security mainframe, or he signs away his soul—and then she does exactly what she always intended to do. The audience’s suspicion of her motives is rewarded: we were right all along, and we get to feel the satisfaction of knowing that the woman in the red dress is never to be trusted.

So why does her target never seem to suspect what we as an audience know from the very start: that the red dress is a warning sign?

By choosing the red dress, the costumer is inviting the audience to consider that maybe the target does know. The costumer isn’t only telling us about the character who wears it—they are also telling us about the character who she will manipulate throughout the course of the story. Because everyone knows that the red dress is dangerous, and surely this character knows, too. He recognizes the danger—but he is drawn to that danger by the same instinct that draws one to stand near the crumbling edge of a cliff and look down.

His hubris, or his death-wish, or his willful ignorance: one of these will play a major role in his story. Without them, the red dress would be a simple ornament. But the woman in the red dress sees those aspects of her target’s personality, and she crafts her lure accordingly.

The costumer who chooses the red dress is turning the first appearance of the character who wears it into a prologue: here tonight shall be presented a tale of weaponized feminine sensuality, of deception and betrayal, of hubris defeated; a tale of masculine indignation at the revelation that a woman can have an entire life’s worth of motives outside of her interactions with a male protagonist.

In this way, the costumer shows us an entire story in a single garment. It’s the story of the woman who wears it, and the story of the man she will effortlessly seduce and destroy.

It’s the story of the red dress.

Sarah Gailey’s fiction has appeared in Mothership Zeta and Fireside Fiction; her nonfiction has been published by Mashable and Fantasy Literature Magazine. You can see pictures of her puppy and get updates on her work by clicking here. She tweets @gaileyfrey. Watch for her debut novella, River of Teeth, from Tor.com in May of 2017.

Sarah Gailey’s fiction has appeared in Mothership Zeta and Fireside Fiction; her nonfiction has been published by Mashable and Fantasy Literature Magazine. You can see pictures of her puppy and get updates on her work by clicking here. She tweets @gaileyfrey. Watch for her debut novella, River of Teeth, from Tor.com in May of 2017.