Captain Kate Fitzmaurice was born to sail. She has made a life of her own as a privateer and smuggler. Hired by the notorious Henry Wallace, spymaster for the queen of Freya, to find a young man who claims to be the true heir to the Freyan, she begins to believe that her ship has finally come in.

But no fair wind lasts forever. Soon Kate’s checkered past will catch up to her. It will take more than just quick wits and her considerable luck if she hopes to bring herself—and her crew—through intact.

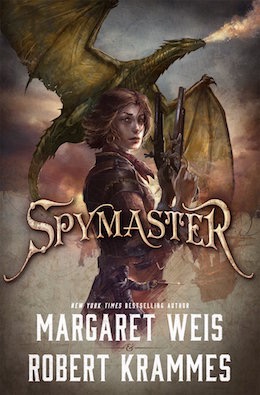

Spymaster is the start of a swashbuckling adventure from Margaret Weis and Robert Krammes—available March 21st from Tor Books.

ONE

Sir Henry Wallace sat at a table in the small cabin aboard the Freyan ship HMS Valor, dunking a ship’s biscuit in his coffee in an effort to render it edible and reading the week-old newspaper.

“Ineffable twaddle,” said Sir Henry, scowling. He motioned with his egg spoon to an illustration and read aloud the accompanying tale. “‘The gallant Prince Tom, heedless of the many grievous wounds he had suffered in the course of the fearsome battle, raised his bloody sword, shouting,“If we are to die today, gentlemen, let history say we died heroes!”’ Pah!”

Sir Henry tossed aside the newspaper with contempt.

“Your Lordship is referring to the latest exploits of the young gentleman known in the press by the somewhat romantic appellation of ‘Prince Tom,’ ” said Mr. Sloan. “I have not read the stories myself, my lord, but I understand they have garnered a great deal of interest among the populace, such that the newspaper has trebled its circulation since the series began.”

Sir Henry snorted and, after tapping the crown of the soft-boiled egg with his spoon, removed the shell and began to eat the yolk. At that moment the ship heeled, as a gust of wind hit it, forcing him to grab hold of the eggcup as it slid across the table. He looked up, frowning at Mr. Sloan, who had rescued the coffee.

“I haven’t been on deck yet this morning,” said Henry. “Is there a storm brewing?”

“Wizard storm, my lord,” said Mr. Sloan. “Blowing in from the west.”

Henry heard a distant rumble of thunder. “At least those storms are not as frequent or as bad as they used to be when the Bottom Dwellers were spewing forth their foul contramagic.”

“God be praised, my lord,” said Mr. Sloan.

“A dreadful war that left its mark on us all,” said Henry, falling into a reflective mood as he drank his coffee. “I think about it every time there is a storm. We wronged those poor dev ils, sinking their island and dooming them to the cruel fate of living in relative darkness at the bottom of the world. Small wonder that even after hundreds of years, they sought their revenge on us.”

“I confess I find it hard to feel much sympathy for them, my lord,” said Mr. Sloan. “Especially given the terrible fate they intended to inflict on our people. Thank God you and Father Jacob and the others were able to stop them.”

“I will never forget that awful night,” said Henry. “I thought we had failed and all I could do was wait for the end. Alan, bleeding to death…”

He fell silent a moment, remembering the horror, the pain of his wounds. He had spent months convalescing and months beyond that battling the nightmarish memories. Not wanting to give them new life, he shook them off and managed a smile. “And there you were to save us, Mr. Sloan, your face ‘radiating glory’ as the Scriptures say of the angels.”

“You were delirious at the time, my lord,” said Mr. Sloan with a faint smile.

“I was not,” said Henry. “You saved our lives, Mr. Sloan, and I do not forget that. As for the Bottom Dwellers, we couldn’t let them continue sacrificing people in their foul blood magic rituals and knocking down our buildings with their contramagic.”

“Indeed not, my lord,” said Mr. Sloan.

“Even if the war did bankrupt us,” Henry added somberly.“Fortunately the crystals will help ease that burden.”

The ship rocked again, causing Mr. Sloan to stagger into a bulkhead.

“Please sit down!” Henry said. “You stand there hunched like a stork and being tossed about. I cannot function if you are laid up with a cracked skull.”

Mr. Sloan sighed and reluctantly seated himself opposite Sir Henry on the bed, a shocking liberty that was harrowing to the soul of Mr. Sloan, who normally would have been standing or respectfully seated in a chair as he attended to his employer, but for the sad fact that the cabin was small with a low ceiling. Being above average height, Mr. Sloan was forced to stand with his head, back, and shoulders bent at an uncomfortable angle.

HMS Valor was a massive warship, with three masts, eight lift tanks, four balloons, and six airscrews. Her two full gun decks carried twenty twenty-four-pound cannons, thirty eighteen-pound cannons, and twenty nine-pound cannons, as well as thirty swivel guns on the main deck. She was a ship designed for war, not for the comfort of those who sailed her.

Having finished his egg, Henry left the past to return to the present. “If all these fanciful stories about Prince Tom did was to increase the circulation of this rag, I would not mind. But these stories are doing considerable harm, not the least of which is forcing you to sit on a bed with your chin on your knees.”

Mr. Sloan was understandably mystified. “I am sorry, my lord, but I fail to see the connection between the prince and the bed.”

“The reason we are on board Admiral Baker’s ship is directly related to this so-called Prince Tom,” said Sir Henry. “Her Majesty the queen complained to me that her own son, the real crown prince, comes off badly by comparison to the pretender. She ordered me to take His Royal Highness on this voyage in order to show the populace a more heroic aspect to his nature. Thus here we are: I have to play nursemaid to HRH while he is on board the flagship, and we find ourselves in these cramped quarters instead of our usual more commodious accommodations aboard the Terrapin.”

The ship heeled, this time in a dif fer ent direction. The thunder grew louder and the room darkened as clouds rolled across the sky, blotting out the sun.

“I must confess I wondered why His Highness was traveling with us, my lord,” said Mr. Sloan, deftly whisking away the empty eggcup and pouring more coffee. Henry kept a firm hold on the coffee cup. “I am sorry to say His Highness does not appear to be enjoying the voyage.”

“Poor Jonathan hates sailing the Breath,” said Henry. “He was sick as a dog the first two days out. He’s being a damn fine sport about it though. He knows what his mother is like when she fusses and fumes. Easier to give way to her fancies, though I’m sure he’d much rather be back home in his library with his books. He’s found a new obsession: King James the First. Says he’s discovered some old letters or something about the murder of King Oswald that reveal James in an entirely new light.”

Mr. Sloan shook his head. “A match to gunpowder, my lord.”

“The whole damn powder keg could blow up in our faces,” said Henry. “This blasted Prince Tom craze put the idea into Jonathan’s head. I warned His Highness to drop the matter, but Jonathan gave me that professorial look of his and said history had maligned his cousin and that it was his duty as a historian to seek the truth. Once HRH has made up his mind to proceed, nothing will budge him. He’s like his mother in that regard.”

“Perhaps Master Yates might be of assistance in the matter, sir,” suggested Mr. Sloan. “Simon could offer his help in the research.”

“By God, there’s a thought!” said Henry, wiping his lips with his napkin. “Simon could stop His Highness from going off on one of his tangents or, at the very least, keep what ever Jonathan discovers out of the press. I can see the headlines now: ‘The Crown Prince of Freya Proves He Has No Claim to Throne.’ ”

“Let us hope it will not come to that, my lord,” said Mr. Sloan.

“We will put our faith in Simon, as always. He did not let me down in the matter of the crystals. He has discovered the formula and knows how to produce them. He only needs access to the Braffan refineries. Once the Braffans grant us that, he is ready to launch into production. Soon the Tears of God will be powering our ships. The navies of other nations— including Rosia— will have to buy the crystals from us, and we will charge them dearly!”

Henry drank his coffee.“Speaking of Braffa and the negotiations, I suppose we had better deal with these dispatches. How old are they?” He eyed the pile of letters and newspapers with a gloomy air.

“Some were delayed more than a fortnight, I fear, my lord,” said Mr. Sloan. “The mail packet only just caught up with us.”

“One would think we were living back in the Dark Times,” said Henry irritably.

“Sadly true, my lord,” said Mr. Sloan. “I have placed those I deemed most urgent on top.”

He held out a small packet of letters that smelled faintly of lavender. “I thought you would like to read these from your lady wife in private.”

Sir Henry Wallace, spymaster, diplomat, assassin, trusted advisor to the queen, member of the Privy Council, and long considered by many to be the most dangerous man in the world, smiled as he took his wife’s letters and thrust them into an inner pocket.

He then perused the dispatches. His smile changed to a grimace as he read the first, which was from an agent known simply as “Wickham” living in Stenvillir, the capital of Guundar.

Henry slammed down the coffee cup, spilling the liquid. Mr. Sloan reacted swiftly, jumping off the bed to mop up the coffee before the small flood reached the remaining dispatches.

“The Guundarans are moving on Morsteget!” Sir Henry exclaimed, waving the dispatch. “According to Wickham, their parliament passed a resolution proclaiming Guundar’s right to the island and voting to establish a naval base there. Fourteen ships set sail for Morsteget weeks ago and I am just now learning about it! These delays in receiving mail have to end, Mr. Sloan. I am seriously considering employing my own griffin riders.”

“The expense, my lord—”

“Hang the expense!” Henry said savagely. Jumping to his feet, he promptly cracked his head on the low ceiling. “Ouch! Bloody hell! No, don’t fuss. I am all right, Mr. Sloan. The devil of it is that we cannot stop Guundar from annexing Morsteget and King Ullr knows it.”

“As bad as that, my lord?”

“Oh, we will make a fine show of being outraged,” said Henry, seething. “The House of Nobles will pass a resolution in parliament, Her Majesty will send a strongly worded protest, and we will boycott Guundaran wine, which is so sweet no one drinks it anyway. But that will be the extent of our fury.”

Henry resumed his seat, rubbing his sore head. Lightning illuminated the cabin in the bright purple glow that was the hallmark of the wizard storm: the clash of magic and contramagic. The thunderclap was some time in coming; Henry judged that the storm was going to miss them, prob ably passing to the north.

“At least I can use this move by King Ullr to impress upon the Braffan council that Guundar is a dangerous ally. He has gobbled up this valuable island and has his eye on the Braffa homeland,” Henry said. “I wonder if those damn Guundaran ships are still skulking about the coastline.”

He sifted through the pile of documents, picked up another dispatch, this one from his agent in Braffa, and swiftly read through it. “The two Guundar ships remain in port in the Braffan capital. The Rosian ships have departed. Not surprising. King Renaud is planning to turn his attention to the pirates in the Aligoes. And speaking of the Aligoes, make a note that I need to speak to Alan about finding a privateer to take his place, since he has quit the trade and become respectable.”

Mr. Sloan made the notation with a smile. After years serving his country as a privateer, Captain Northrop had finally been granted his dearest wish: a commission in the Royal Navy.

“But what to do about Guundar?” Henry muttered, returning to his original prob lem. “I made a mistake advising the queen to request King Ullr’s help in freeing the Braffan refineries from the Bottom Dwellers. We have given that minor despot delusions of grandeur.”

“You had no choice, my lord,” said Mr. Sloan in soothing tones. “You could not allow the Bottom Dwellers to continue to hold those refineries and after the war, neither the Freyan forces nor those of the Rosians were strong enough to oust them.”

“You are right, of course, Mr. Sloan,” said Henry. “Thank God for Simon and the crystals. Without him Freya would be in dire straits.”

He sifted through the dispatches. “I suppose we must let King Ullr have his little island, at least for the time being. Our people will grouse, but once we have this treaty with Braffa and we put the crystals into production, money will flow into the royal coffers, our economy will improve, and our people will forget about Guundar and continue to waste their time reading about the fictional exploits of Prince Tom.”

“Might I play dev il’s advocate, my lord?” Mr. Sloan asked.

“One of the many reasons you are in my employ, Mr. Sloan. Please, do your damnedest.”

Mr. Sloan smiled.“If we make a secret treaty with Braffa to produce the crystals, won’t we be breaking the Braffan Neutrality Pact?”

“Not so much a break as a hairline fracture, Mr. Sloan,” said Henry. “The other signatories won’t like it, but if we keep the agreement secret until the crystals are ready to come to market, it will be too late for them to protest.”

The two continued to work their way through the dispatches and letters. Henry longed to read the letters from his wife, to hear about young Henry and his recent exploits, but duty called and he forced himself to concentrate on official business. Mr. Sloan handed him a letter from his rival spymaster, the Countess de Marjolaine of Rosia, ostensibly written to the gamekeeper on her estate. One of Henry’s agents in Rosia had intercepted the letter, and Henry was trying to figure out if the missive was in fact to her gamekeeper and did in fact refer to poachers or if it was a message of a more sinister nature to someone with the code name “Gamekeeper.”

Henry had long suspected the Rosians of supporting the Marchioness of Cavanaugh in her ridicu lous attempts to make her son— the Prince Tom of whom the newspapers were so enamored— king of Freya. King Renaud of Rosia had said publicly that Rosia had no business meddling in Freyan affairs, but Henry had discovered that the Rosians were privately funding the prince’s cause, hoping to destabilize the Freyan monarchy.

Henry was interrupted in his code-breaking by a stentorian bellow from the deck above. Henry raised his head.

“Was that Randolph shouting for me? What the devil—”

He could hear drums beating to quarters, feet pounding on the deck above, men running to their stations. The next moment someone was frantically pounding on the door. Mr. Sloan opened the door to find a breathless midshipman.

“The admiral’s compliments, my lord; you’re wanted on deck.”

Henry and Mr. Sloan exchanged alarmed glances. Admiral Baker was known by the men who served under him as “Old Doom and Gloom” for his pessimistic outlook on life. He also was known to keep a cool head in a crisis.

“Randolph would not bellow without cause. This does not bode well,” said Henry.

Mr. Sloan assisted Henry with his coat. Henry slipped his arms into the tailored, dark blue wool frock coat, which he wore over a blue waistcoat and white shirt. He grabbed his tricorn as he was leaving and firmly clamped it on his head, mindful of the strong wind gusts.

Mr. Sloan followed. The private secretary wore the somber, dark, but-toned-up, high-collared coat preferred by those who observed the conservative beliefs of the Fundamentalists. He then checked to make certain his pistol was loaded. Having served as a marine in the Royal Navy, Franklin Sloan was well aware of the dangers of sailing the Breath.

When the two arrived on deck, Mr. Sloan remained discreetly in the background, while Henry advanced to join the admiral, the ship’s captain, and His Royal Highness on the quarterdeck. None of them immediately noticed Henry. The captain and the admiral were both focusing their spyglasses on the distant shore. Crown Prince Jonathan stood nearby, muffled in a long boat cloak that was whipping in the wind. His face, vis i ble above the tall, turned-up collar, was tinged with green.

Henry bowed to the prince, then glanced at the sky. Clouds roiled overhead, gray and ominous and flickering with purple lightning. A smattering of rain was falling, but he could see that the worst of the storm was, as he had thought, heading north, bearing down on the Braffan city of Port Vrijheid.

He cast a look around the horizon. From the ominous tone of Randolph’s bellow and now the sounds of guns being run out, he expected nothing less than a Rosian man-of-war bearing down on them. The only other ship in sight was their own escort, the Terrapin.

Henry looked toward Port Vrijheid. The city appeared quite peaceful. No pirate ships attacking, no thundering of cannon fire, no smoke billowing into the air. The port was almost empty, but that was not unusual. Prior to the Bottom Dweller War, he would have seen the large freighters that carried the liquid form of the magical Breath setting out for vari ous parts of the world. Only a few small merchant ships were in port today and none of the freighters, for the refineries had suffered severe damage during the war and were still being rebuilt.

Henry wanted to go speak to Randolph, to find out the nature of the emergency. Protocol demanded that he first greet the prince, however. Jonathan appeared relieved to see him, for he gave Henry a faint smile and a nod.

Jonathan, Crown Prince of Freya, was twenty-two years old, was married, and had done his duty by already producing an heir. The only living child of Queen Mary of Chessington, the prince was an affable, serious-minded young man far more suited to a career as university professor than future monarch.

Passionately fond of history, Jonathan had even written a book, titled The Six Sigils of Magic as the Foundation Blocks of the Sunlit Empire, much to the chagrin of his mother. Queen Mary had never read a book in her life and seemed to feel there was something plebeian about writing one, rather as if her son had taken up bricklaying.

The queen was an active woman, fond of shooting grouse and chasing foxes. She found it difficult to understand a son who would rather read in the library than go galloping about the countryside.

The ship lurched at that moment, causing the prince to hurriedly grab hold of a mast.

“How are you feeling, Your Highness?” Henry asked.

“A bit queasy,” Jonathan replied with his customary frankness. “Never been in a wizard storm out in the Breath. Damn fine sight. Wouldn’t have missed it. Don’t fret over me, Sir Henry. I believe the admiral needs you. Trou ble of some sort.”

Henry bowed and hurried over to join his friend.

“What’s going on, Randolph?” Henry asked. “Judging by your bellow, I thought we were sinking with all hands.”

In answer, Randolph took the spyglass from his eye and thrust it at Henry.

Randolph Baker had never been handsome, and his bald head and florid face were not improved by scars from burns he had suffered during the war, when he had dragged a burning sail off one of his officers. His face was redder than usual, verging on purple; his perpetual scowl was grimmer and deeper.

Henry put the spyglass to his eye. “What am I looking at?”

“You’ll see,” Randolph growled.

Henry swept the shoreline just north of the port. He suddenly stopped, stared, and then moved the spyglass slowly, concentrating, making certain he was seeing what he feared he was seeing.

“Damnation!” Henry muttered.

He should have been looking at two old-fashioned Guundaran warships, sent to Braffa to try to convince a skeptical world that King Ullr was a leading actor, no longer a spear-carrier. Instead, Henry counted ten ships of the line, six frigates and two massive troop carriers, all in full sail and all flying the blue and gold ensign of Guundar.

A bitter taste filled Henry’s mouth, a taste to which he was not accustomed: the taste of defeat. He tried telling himself he and Randolph were both jumping to conclusions, but he knew quite well they weren’t.

“Morsteget, my ass!” Henry said. “That was a bloody ruse! Ullr is here to snap up Braffa! Damn and double damn!”

He shut the spyglass with a snap and handed it back to Randolph. The Guundaran ships had sighted the approach of HMS Valor. Observing that one of the ships was flying the Freyan royal arms, indicating that royalty was aboard, the Guundaran flagship, the HMS Prinz Lutzow, fired a salute.

Henry saw that the Prinz Lutzow was also flying the royal arms of Guundar, which meant that some member of their monarchy was on board. He swore beneath his breath. King Ullr, without a doubt. Come to claim his conquest. Randolph had noticed as well.

“I suppose we have to salute the bastard,” he said.

“Unfortunately, yes,” said Henry.

“Signal from the Terrapin, sir!” shouted a midshipman.

“That will be Alan, wanting to know what’s going on,” Randolph remarked.

The Terrapin was raising and lowering signal flags at such a furious rate that the midshipman on board Valor responsible for reading them could scarcely keep up.

“What do we tell him?” Randolph shouted as the Valor fired her cannons, returning the salute. A gust of wind almost took off Henry’s hat. He grabbed hold of it as the smoke from the cannons blew past.

“You tell Alan he is not to start a war,” Henry shouted back.

“Must I?” Randolph asked, frowning. “We could sink three of those frigates before they knew what hit them.”

“Not even you and Alan can take on the entire Guundaran naval force,” said Henry. “We don’t want trou ble. I will handle this with diplomacy. Once this storm ends, I will go ashore and meet with the Braffan council as planned.”

Randolph looked grim. “I’d like to give that bastard Ullr diplomacy— in the form of a broadside!” He glanced sidelong at the prince and lowered his voice. “What about HRH? You were planning on taking him with you.”

“To be humiliated? I won’t give the Braffans or Ullr the satisfaction,” said Henry. “Besides, I still have one card to play— Simon and the crystals.

We know the formula and the Braffans don’t. Something may come of that.”

“Not bloody likely,” Randolph grunted.

“Always the optimist,” said Henry.

“Realist, old chap,” said Randolph. “Realist.”

“I have to tell the prince about the change in plans,” said Henry, sighing. “Let me know when the wind has died down and you think it’s safe to go ashore.”

Randolph nodded and turned back to closely observing the Guundaran ships.

Henry signaled to Mr. Sloan, who had remained discreetly in the background and now advanced to meet him.

“You heard the news, Mr. Sloan?”

“Yes, my lord. Most unfortunate.”

“I have been outwitted by King Ullr, a barbarian whose mental processes are taxed by trying to decide what to have for dinner!” Henry said bitterly. “He fooled us into thinking his blasted fleet was sailing to Morsteget, when in real ity they were sailing for Braffa. And now I will have to go ashore and meet the old fart and listen to him gloat.”

“We do have the crystals,” said Mr. Sloan.

“That we do, Mr. Sloan. The Tears of God. Tears that are more valuable than diamonds.”

“Will I be accompanying Your Lordship?”

“Yes, Mr. Sloan. I’ll need you to take notes when I meet with the Braffans. You prepare for the journey. I must go speak to His Highness.”

The rain had stopped and the wind had shifted. The storm had passed, though a few ragged clouds still boiled overhead. Henry was crossing the deck when a blinding flash of purple lightning streaked down from the sky, striking so close he could smell the sulfur. The lightning was accompanied by a nearly simultaneous thunderclap and the sickening sound of rending and cracking wood.

The mainsail boom crashed down onto the deck. Prince Jonathan disappeared beneath a tangle of rope, splintered wood, and sailcloth.

TWO

Time distorted for Henry. He watched the broken boom fall, the sails crumple, the rigging twist and cascade downward, all with such agonizing slowness that every moment was imprinted on his brain.

The prince vanished amid the wreckage, and suddenly time accelerated, with subsequent events happening in a confusing blur. The sight of Mr. Sloan rushing past him, shouting for help, jolted Henry to action.

He ran to join Mr. Sloan and the others as they worked frantically to free the prince. Some grabbed axes and knives. Seeing this, Randolph shouted that no one was to start chopping until they knew what had become of the prince, and try to determine his location.

Henry peered through the wreckage and thought he caught a glimpse of the boat cloak the prince had been wearing.

“I see him,” Henry cried. “He’s not moving. Your Highness! Jonathan!”

Every one waited in anxious silence. There was no response.

“Clear away this bloody mess!” Randolph ordered, grabbing hold of a length of rope and hauling it off.

They worked feverishly to remove the tangle of sail and rope and splintered wood and eventually found the prince lying beneath the boom, which had fallen across his chest.

Jonathan was unconscious, his face deathly pale and covered with blood. For a terrible moment Henry feared he was dead. The ship’s surgeon felt for a pulse and announced that His Highness was alive. The good news caused the sailors to raise a cheer. Randolph summoned the strongest men on board ship, and together they lifted the heavy boom and held it steady until Mr. Sloan, under the surgeon’s direction, was able to grasp the prince by the shoulders and gently and carefully drag him to safety.

They placed Prince Jonathan on a litter and carried him to his cabin. Henry stood by, feeling helpless, while the surgeon and his mate stripped off the prince’s clothes. Henry noted that the surgeon looked grave as he poked and prodded. The prince had an ugly cut on his head and a large purplish red bruise on his chest.

Completing his examination, the surgeon was more optimistic.

“His Highness is very lucky. He has two broken ribs, but his skull remains intact,” the surgeon reported. “His lungs were not affected.”

Prince Jonathan regained consciousness moments later, wondering where he was and what had happened. When the surgeon asked him if he could move his feet, the prince obliged.

“No damage to the spine, Your Highness,” said the surgeon. “I predict a full and complete recovery. I will give you laudanum for the pain and to help you rest.”

“I will remain with His Highness,” said Henry.

The surgeon eyed him. “No, you won’t, my lord. Not with those hands of yours resembling sides of beef. You come below with me.”

Henry looked at his hands and was surprised to find he had ripped most of the skin off his palms, leaving them bloody and raw. He accompanied the surgeon to the sick berth. The surgeon applied a healing ointment, bandaged his hands, and recommended rest and brandy.

Mr. Sloan accompanied Henry to his cabin, then left in pursuit of brandy. He returned to find Henry attempting to change clothes and having a difficult time of it.

“What are you doing, my lord?” Mr. Sloan asked.

“Dressing for my meeting with the Braffan council,” said Henry. He scowled at the bandages on his hands, which prevented him from doing the simplest tasks, such as buttoning his trousers.

“Be reasonable, my lord,” Mr. Sloan said. “You have missed the meeting which was scheduled for ten of the clock. The time is now almost noon. And the surgeon said—”

“Devil take the surgeon and the clock!” said Henry angrily. “I must speak to the Braffans. Help me on with this blasted shirt and give me some of that brandy.”

Mr. Sloan frowned his disapproval, if he didn’t speak it. He assisted with the shirt and waistcoat and frock coat, wrapped a boat cloak around Henry’s shoulders, then poured some brandy into a tin cup. Henry drank it at a single gulp.

“Have the pinnace waiting for me, Mr. Sloan. I will pay my respects to His Highness and then join you on deck.”

Henry found Jonathan sitting up in bed. The prince made light of the accident.

“My own damn fault, really,” said Jonathan.“I should have gone below when the storm hit. As it is, the surgeon says I shall be up and about in a few days.”

“I am thankful to hear that, Your Highness,” said Henry. “With your permission, I would like to proceed to my meeting with the Braffan council. I can remain here, if Your Highness has need of me—”

“No, no, carry on,” said Jonathan. “I saw all those Guundaran ships in port. I gather something is amiss.”

“Hopefully to be set to rights, Your Highness,” Henry replied.

“Do you think the Guundarans are breaking the neutrality pact, Sir Henry?” Jonathan asked, frowning.

“I should not like to venture to say, Your Highness,” said Henry.

“But you think it likely,” said Jonathan. “Good luck and a safe journey, my lord. Report to me on your return.”

Henry bowed and took his leave. He found the crew of the pinnace waiting for him. Mr. Sloan had already boarded, and he assisted Henry to his seat. The boat was small, designed to ferry supplies, crew, and passengers to and from shore. The helmsman inflated the single balloon and then sent magic flowing from the brass helm to the air screws and the lift tanks. The pinnace rose from the deck of the ship with a slight lurch and then sailed toward the pier.

Henry thrust the shock and the upset and the stinging pain of his palms out of his mind. He would need all his faculties to deal with the Braffans. He did not say no, however, when Mr. Sloan offered him another gulp of brandy from a small pocket flask.

As they approached the harbor, Henry saw two people, both of whom he recognized, standing on the pier in the shelter of a boat house. One was a middle-aged woman in a rain-soaked bonnet. The other was a tall, broad-shouldered man in a military uniform and a plumed gold-braid-trimmed bicorn. They had apparently been about to board a pinnace of their own. Seeing Henry’s approach, they had seemingly deci ded to wait.

“What are those two doing on the dock?” Henry wondered.

“I would hazard a guess that since you did not attend the meeting, they were about to sail to the Valor to speak to you,” Mr. Sloan suggested. “Do you know them, my lord?”

Henry grunted. “The woman is Frau Aalder, a member of the Braffan council. She was with me at the refinery the day the Bottom Dwellers attacked. She formed a bad opinion of me during that incident— not entirely unwarranted I must confess, given that Alan and I threatened to sink the ship on which she was sailing.

“The tall man with all the medals and gold braid and plumed bicorn is His Majesty, King Ullr Ragnar Amaranthson of Guundar. I have no idea how he came by the medals. As far as I know the man has never seen combat, if you don’t count the duels he fought in his youth.”

The pinnace docked, the crew lowered the gangplank, and Henry and Mr. Sloan stepped onto the pier. Henry walked across the dock to meet Frau Aalder and the king. Mr. Sloan remained at a distance, yet keeping close enough to hear the conversation. Mr. Sloan could not take notes, for this conversation would be unofficial and off the record. But he had an excellent memory and would make a record of it later.

Henry bowed to the king and gave Frau Aalder a curt nod.

“I apologize for my late arrival,” Henry said. “Our ship was struck by lightning with the result that I was unavoidably delayed. We can now proceed—”

Frau Aalder interrupted. “The meeting is over. Ullr and I were coming to tell you. You know Ullr, of course. What the devil did you do to your hands?”

Henry stared at the woman, disgusted at her gauche remarks, and pressed his lips together to keep his rising anger in check. He saw no need to reply. Frau Aalder was considered rude, even by the relatively relaxed mores of the Braffans. King Ullr cast her a glance of disdain and tried to make up for her crudeness.

“We were sailing over to the ship hoping to visit Crown Prince Jonathan,” said King Ullr, speaking passable Freyan with a thick Guundaran accent. “We were going to invite His Highness to dine aboard the Prinz Lutzow this evening.”

“I am certain His Highness would have been glad to come, Your Majesty, but unfortunately the crown prince is indisposed,” said Henry.

“I am sorry to hear that,” said King Ullr. “Perhaps another time. We wanted to tell His Highness how much we enjoyed reading his book. Perhaps you can pass along—”

“Never mind about books now, Ullr!” said Frau Aalder, who had been impatiently tapping her foot during the niceties. “The council originally agreed to meet with you, Wallace, to discuss Freyan offers of help to rebuild our refineries. Such help is no longer required. Braffa is now a protectorate of Guundar.”

“Protectorate!” Henry repeated, amazed.

“As you know, we have no standing military of our own,” Frau Aalder continued. “Our nation is too small to fund one. Guundar has offered to establish a naval base on Braffa, and to assist us to build up our defenses. During that time, their ships will patrol the refineries and our coastline.”

Henry saw triumph gleam in the king’s eyes. In that moment, he would have given a great deal to see a boom fall on King Ullr.

Henry kept his face expressionless as he considered his response. An outward show of anger could reveal Freya’s desperate need for the money from the sale of the crystals. To say nothing of the fact that the Freyan navy required the liquid form of the Breath of God in order to condense it down to manufacture the crystals. Anger could hurt his cause. He deci ded to respond with the sorrow of someone who has been betrayed by a friend.

“I trust the Braffan council realizes, Frau Aalder, that such an agreement breaks the terms of the Braffan Neutrality Pact,” Henry said. “Freya made that pact in good faith which, I am sorry to discover, was apparently not shared.”

King Ullr gave a derisive snort. “Neutrality pact be damned! You came to Braffa, Sir Henry, hoping to persuade the council to allow your government to take over the refineries. We have simply beat you to the punch, as your Freyan pugilists say.”

Henry turned a cold eye upon the king. “Since I am not to be permitted to speak to the council, you will never know, will you, Your Majesty?”

Frau Aalder intervened with the exasperated air of a governess separating naughty boys. “As for breaking the neutrality pact, that’s rubbish. Guundar is acting to enforce the pact that you planned to break. So, you see, Wallace, you have no reason for complaint and so you may inform your queen.” Frau Aalder plucked at King Ullr’s gold-braided sleeve. “We should leave now, Ullr. I am certain Wallace is eager to return to his ship before another storm hits.”

“We see no storm in the offing, madame,” said King Ullr. Stepping away from her reach, he walked closer to Henry. “And our business with Sir Henry is not concluded.”

“Yes, it is,” said Frau Aalder irritably. “I have nothing more to say to Wallace.”

“But we do, madame,” said King Ullr, fixing her with an imperious stare.

Frau Aalder glowered and fumed, reminding the king that he wanted to make an inspection tour of the refineries. King Ullr was not to be deterred from speaking to Henry, who found this altercation between the two intriguing. Frau Aalder was clearly trying to whisk King Ullr away. Henry wondered why, and the next moment he had his answer.

King Ullr, brushing aside Frau Aalder, drew near Henry until they were practically toe-to-toe, attempting to use his height and bulk to intimidate him. “We have heard rumors that the Braffans developed a crystalline form of the Breath known as the Tears of God. What do you know about such crystals, Sir Henry?”

Before Henry could reply, Frau Aalder literally pushed her way into the conversation, shouldering between the two men.“I have told you, Ullr, that those rumors are completely unfounded.”

As she said this, she shot Henry a warning glance from beneath the brim of her bedraggled bonnet and very slightly shook her head, urging him to silence.

Henry responded with a derisive smile, reminding her that he knew the rumors were not all unfounded. Frau Aalder grew grim.

“We did conduct some research,” she admitted. “But the experiments failed and the program was halted. No need to ask Wallace. He knows nothing about it. And now we really must leave, Your Majesty. We have that inspection tour scheduled…”

King Ullr had seen Henry’s smile and was not to be deterred. “Our agents tell us that the Rosians unexpectedly came into possession of several barrels of these crystals that do not exist. I suppose it was a coincidence that the appearance of the crystals in Rosia occurred immediately after you, Sir Henry, and your friend, Captain Stephano de Guichen, visited one of the Braffan refineries. The captain is reputed to have used the crystals to raise an enormous fortress off the ground and sail it Below. And yet you claim to know nothing of any of this.”

“I was in Freya at the time, fighting my own battle with the Bottom Dwellers, Your Majesty,” said Henry grimly. “As for Captain de Guichen— now the Duke de Bourlet—he is a Rosian and thus no friend of mine. He is, however, a close friend to King Renaud and a hero to the Rosian people.”

Henry paused, then added in milder tones, “Perhaps I should remind Your Majesty that King Renaud is a signatory to the Braffan Neutrality Pact and that His Majesty will be extremely displeased to hear of Guundar’s interference. The Rosian navy is dependent on the liquid form of the Breath to fuel their ships. I doubt King Renaud will be pleased to hear of this new ‘protectorate.’ ”

“I find it hard to believe that you know nothing about these crystals, Sir Henry,” King Ullr insisted stubbornly.“Captain de Guichen could not have flown a massive stone fortress to battle at the bottom of the world without them.”

“And I find it hard to believe that you are coming perilously close to calling me a liar, Your Majesty,” Henry said angrily.

“Actually, Ullr, you are calling me a liar!” said Frau Aalder, glaring at both men. “I told you Wallace knows nothing about the crystals! We are late for our appointment.”

Frau Aalder might be rude and crass, but she was also clever, counting on the fact that King Ullr could not afford to offend her, the representative of his new ally. King Ullr realized he had gone too far and he was forced to let the matter drop.

“Forgive me, madame,” King Ullr said in frozen tones. “Such was not my intent.”

“I should hope not,” said Frau Aalder, sniffing. She was actually almost cordial to Henry. “We will be in touch, Wallace. The council knows the importance of the Blood of God to the navies of the world and we hope to resume production as soon as possible and get it out on the market.”

“At an exorbitant price, no doubt,” said Henry, his lip curling.

“If you find the liquid too expensive, perhaps your navy could go back to sailing using the old-fashioned means,” said King Ullr.“Although I doubt even God’s Breath could float that monstrosity.”

He cast a glance at HMS Terrapin, sailing in the Breath alongside the Valor. The hull of the Terrapin was covered with specially designed magical metal plates that gave the ship her name. Their magic made the ship practically impervious to gunfire, but the sheets of metal were extremely heavy. The “old-fashioned means” to which the king referred were tanks filled with the Breath of God. The magically enhanced gas could not provide the lift needed to keep the Terrapin afloat.

Henry was aware he had lost the battle and he could do nothing now except claim his wounded and retire from the field. He could at least fire a final parting shot.

“I will take this news back to Her Majesty,” he said. “In the interim, I urge you, Frau Aalder, and the other members of the Braffan council to recall what happened when King Ullr’s forebearers took their neighbors ‘ under protection.’ ”

King Ullr stiffened, his face flushed an angry red. The ancient Guundarans were reputed to have been barbarians who preyed upon their neighbors, looting, burning, and plundering. The Guundarans had long sought to live down this reputation; King Ullr was so outraged Henry thought the king might actually challenge him to a duel on the spot.

As the king advanced, his hand on the hilt of his sword, a gust of wind left over from the storm chose that moment to carry off the king’s tall, plumed bicorn and send it bounding along the pier.

Henry kept a straight face as one of the king’s aides ran to fetch the wayward hat, though he did allow his lips to twitch. Frau Aalder was not so kind. She laughed out loud. King Ullr cast Henry a furious glance, turned on his heel with military precision, and, retrieving his hat, thrust it under his arm and angrily stalked off.

Henry removed his own hat for dignity’s sake, lest the wind blow it off, too. He joined Mr. Sloan, and the two slowly walked back to the pinnace.

“What did you think, Mr. Sloan?”

“Frau Aalder is an extremely unpleasant woman, my lord,” Mr. Sloan replied.

“I wish I’d let the Bottom Dwellers shoot her,” Henry muttered.“At least the meeting ended on an amusing note.”

“If you are referring to the wind gust carry ing off the king’s hat, I have always said God is a Freyan, my lord,” Mr. Sloan observed.

Henry smiled. “So you have, Mr. Sloan, but that wasn’t what I meant.”

He paused a short distance from the pinnace and lowered his voice. “The matter of the crystals. Frau Aalder and the council are lying to their new ‘protector.’ She was there when Captain de Guichen and I seized the crystals. And I am certain Ullr knows she’s lying, though he can’t prove it.”

“Why would the Braffans lie about the crystals, my lord?” Mr. Sloan asked.

“I am wondering that myself,” said Henry. “At a guess, I would say they don’t want King Ullr to know that the crystals exist. She must know that both we and the Rosians are studying the crystals in our possession, trying to learn how to manufacture them. The Rosians have failed thus far and, from what my agents tell me, they are going to cease working on it in order not to waste any more of the crystals.”

“It would seem King Ullr has bought a pig in a poke, my lord.”

“I believe you are right, Mr. Sloan. Let us say that we start manufacturing the crystals in Freya. Three crystals can lift a frigate off the ground, replacing several barrels of the liquid form of the Breath. All the navies of the world would flock to purchase crystals from us. The price of the liquid would plummet and Ullr would realize he had made a bad bargain.”

Henry was grim. “Unfortunately, to make the crystals, we need the liquid form of the Breath. King Ullr will see to it that we pay through the nose, such that we will not be able to afford to manufacture the crystals. This is a disaster, Mr. Sloan. An unmitigated disaster.”

“I am certain you will find a way to remedy the situation, my lord,” said Mr. Sloan.

Henry only shook his head and boarded the pinnace.

The journey back to the Valor was rough. The gusty winds that had carried off the king’s hat blew the pinnace all over the sky and made landing treacherous. The coxswain in charge knew his business, however, and safely brought the boat down onto the deck. Sailors rushed to secure it.

Randolph was on hand to meet them. When he saw Henry, he raised an eyebrow. Henry shook his head, letting him know he had failed. Randolph shrugged. With his customary pessimism, he had been expecting nothing else. The flag captain of the Valor ordered the crew to weigh anchor and prepare for return to Freya.

That evening, Captain Alan Northrop of the Terrapin sailed to the Valor to join his friends for dinner.

Alan, Henry, Randolph, and Simon Yates had been friends for over twenty years, since their days at university. They had called themselves “the Seconds,” for they had discovered that each was

a second son, meaning their older brothers would inherit the family fortunes, leaving each of the younger brothers to fend for himself.

In their numerous adventures during their university days, Henry had been the cunning schemer, Randolph the dour pragmatist, Simon the swift thinker, Alan the bold, daring rogue. Their friendship had remained strong through the years. Although Simon was not present, being confined to a wheelchair in his eccentric house in Haever, his friends always kept a place for him at the table and drank a toast in his honor.

The three dined in the admiral’s spacious cabin in the ship’s stern. Conversation was desultory, none of them able to discuss international intrigue in the presence of the servants. Henry had finally found time to read his wife’s letters; he recounted a few of young Henry’s three-year-old exploits to proud smiles from the “uncles,” as his friends considered themselves. After dinner, Randolph dismissed the servants. Mr. Sloan served brandy, cheese, and walnuts, and at last they were able to discuss the day’s events.

“How is His Highness?” Alan asked.

“The prince is resting comfortably,” Henry reported. Not wanting to risk dropping one of Randolph’s fragile crystal snifters with his bandaged hands, he was drinking the brandy from a tin cup.

“Thank God for that,” said Alan.

They had drunk the traditional toast to the queen, but now Randolph raised his glass to the prince. “To His Highness. Long may he reign.”

“I fear the news isn’t all good,” Henry said, holding out his mug for a refill. “The surgeon told me privately that he is worried about the ugly bruise on the prince’s chest. He fears his heart may be damaged. He detects a slight irregularity in the prince’s heartbeat.”

“Damn sawbones! Always making a fuss,” Randolph said in disgust. “Of course the prince’s heartbeat is irregular. Goddamn boom fell on him! Good stiff drink, that’s what he needs. I shall send him a bottle of the ’88 port.”

“How did the meeting go with the Braffans?”Alan asked, finally asking the question that had been on every one’s mind. “What is Guundar up to?”

Henry gave a morose shake of his head.

“As bad as that,” said Alan.

“Worse,” said Henry.

He described his meeting with Frau Aalder and King Ullr.“Braffa is now a protectorate of Guundar.”

“Protectorate!” Randolph repeated with a bellowing laugh. “Might as well ask the goddamn wolf to protect the goddamn sheep!”

“By God, Henry, Guundar broke the neutrality pact!” Alan exclaimed, flushed with excitement and brandy. “This means war!”

Alan had lost his right hand during a fight with the Bottom Dwellers, when his rifle had exploded after being hit by a blast of contramagic. The loss had not slowed him down, nor did it seem to overly concern him. He had practiced until he could wield a sword and shoot with his left hand almost as well as he had with his right.

Three years since the war ended, Alan was growing bored with peace. Henry suspected his friend missed his days roaming the Breath as a privateer, hoping to snap up an Estaran treasure ship or capture a rich Rosian merchantman.

“Keep your voice down, Alan, for God’s sake!” Henry said, annoyed. “Rumors spread like the yellow jack aboard ship! I don’t want half the fleet thinking we’re going to war.”

He tried to set the mug down on the table, but dropped it, spilling brandy. Henry swore, kicked the mug, sending it flying. Mr. Sloan silently retrieved the mug and mopped up the brandy.

Henry muttered an apology, then rose to his feet. “We will talk in the morning.”

“Henry, this is us,” said Alan earnestly. “You can tell us anything.”

“Bloody damn right,” said Randolph.

Henry knew he could. He knew he must tell them someday that Freya was teetering on the edge of a financial precipice. But not to night. His bandages were stiff and uncomfortable, and his hands burned.

“Good night,” said Henry.

As he left, he heard Randolph remark, “Poor old Henry. He looks like the goddamn boom fell on him.”

Henry gave a bitter smile. In a way, he felt as though it had. A boom by the name of King Ullr.

THREE

Six months after the accident on board the Valor, Crown Prince Jonathan was dead.

The royal physician said he died of a bruised heart muscle suffered when the boom struck his chest. To compound the tragedy, the prince’s little son and heir died a fortnight later, a victim of the diphtheria epidemic currently sweeping through Haever. The two were buried side by side in a vault in the great cathedral.

The nation of Freya, having lost both heirs to the throne in a span of weeks, was in shock and mourning. Queen Mary was a widow, past the age of childbearing. The tragic double loss meant that suddenly, the line of succession was in serious jeopardy.

Henry recalled terming the Braffan takeover by Guundar a “disaster.” He reflected grimly that he had not then known the meaning of that word.

He and his wife, Lady Ann, attended the lavish funeral. Heads of state the world over had come to pay their respects. Among them were King Renaud of Rosia and his sister, the Princess Sophia, who had spent time in Freya following the war as a gesture of friendship between the two nations. King Ullr had come, as had a representative of the Braffan council (though not Frau Aalder, for which Henry was grateful!), as well as the monarchs of both Travia and Estara and a host of princes, nobles, bishops, and foreign dignitaries.

Surrounded by a suffocating mass of humanity, Henry was conscious only of a small white casket and the body of the little prince, looking like a waxen doll. The sight of the dead child, who had been the same age as his own son, badly unnerved Henry. During the ser vice, he went down on his knees to pray to a God in whom he didn’t believe to bless and keep his dear boy.

The ser vice was beautiful, sad, and solemn. Henry and his wife escaped as soon as decently possible. They were well aware that with all the dignitaries crowding around her, offering their condolences, Her Majesty would never miss them.

Arriving back home, Henry handed his black top hat and cloak to the footman. His wife removed her black veiled bonnet and her cloak, then rested her black-gloved hand on his arm.

“What a dreadful time this has been,” she said. “You look exhausted, my dear. You haven’t slept in a week. Shall I have tea served in the drawing room?”

“Always thinking of me, little Mouse,” said Henry. “I should be the one worried about you, especially in your condition.”

Lady Ann smiled and placed her hand on her swollen belly. She was six months pregnant with their second child.

“You must be upset,” Henry continued, taking her hand. “You and the prince were cousins. Her Majesty told me you two played together as children.”

His wife was close to the same age as the dead prince; she had only just turned twenty. He was in his forties and he could still not believe his good fortune in obtaining such a woman as his wife. The queen had given Lady Ann to Henry in marriage as a reward for his loyal ser vice, making him Earl of Staffordshire. He had been astonished beyond belief to learn that in addition to the money and the title and the manor house, she brought him love.

Ann was pale and slender, with large eyes and brown hair. The queen had deemed her niece “a sweet child, but mousy,” and “Mouse” had become Henry’s pet name for her. Twenty-five years older than his wife, he marveled every day that she should have fallen in love with him and, more astonishing, that he— hard-bitten and cynical— had fallen in love with her.

“Jonathan was never one for childish games,” said Ann, making a face. “All we ever did together was play checkers. He would very politely beat me and then leave to go read a book. I never really minded, though. He had the most wonderful rocking horse. I loved riding it. He kept it for little Charlie. I suppose it had to be burned with all the rest of his toys, poor lamb.”

Ann wiped her eyes with her handkerchief. Henry gripped her hand.

“Our son is well, isn’t he?” he said with a catch in his voice. “No sign of contagion.”

“He is fine,” Ann replied with a reassuring smile. “We are taking every precaution. Nurse keeps him indoors, away from other children. He doesn’t like being cooped up, though, and I’m afraid he’s been very naughty. He jabbed one of the maids in the leg with that wooden sword Captain Northrop gave him. Hal told her he was a pirate and he was going to make her eat macaroons.”

“Eat macaroons?” Henry repeated, mystified.

“Nurse and I believe he meant ‘marooned,’ ” said Ann.“Now don’t you laugh, Henry! You and Captain Northrop encourage him to play pirates, but he cannot be allowed to stab the servants.”

“No, no, of course not,” said Henry hurriedly. “I will speak to him. And now I’m going to change my clothes. You should rest and put your feet up.”

He kissed her and hastened upstairs to his dressing room. He did not employ a valet, knowing better than most that servants make excellent spies. Shutting the door, Henry sank down in the chair and let his head fall into his hands. His laughter at his son’s exploits had brought him near to tears.

Henry was, as Ann had said, exhausted. During the last month of the prince’s illness, Henry had spent much of the time at the palace, dealing with physicians and the Privy Council and attempting to calm the fears of the House of Nobles. After Prince Jonathan’s death, Henry had been obliged to assist in planning the elaborate funeral and to urge the grief-stricken queen to make a decision about the heir to the throne. Queen Mary refused to even discuss the matter.

Henry rose, splashed cold water on his face, changed his clothes, and joined his wife in the drawing room. Ann poured tea and, at Henry’s request, told Nurse to bring young master Hal to visit his parents. Remembering the small white casket, Henry clasped his son in his arms so tightly that Hal protested.

“Papa, stop! You’re squishing me!”

Henry released the child and studied him anxiously. Hal did look healthy. No sign of a runny nose or fever, the early symptoms of the disease known as the “Child’s Strangler,” so named for the membrane that grew in the throat, causing children to suffocate.

“Henry, you promised you would speak to him,” said Ann with a reproving look.

“I did, indeed.” Henry sat down in a chair, placed his son on his knee, and undertook to lecture him. “Now, young man, I have received a report that you stabbed one of the maids—”

“Polly,” said his wife.

“You stabbed Polly with your toy sword,” Henry continued, trying to sound and look stern. “That was very wrong of you, Hal. A gentleman respects his servants. He does not mistreat them.”

“But Polly wasn’t a servant, Papa,” Hal argued. “We were playing pirate. I was Captain Alan and Polly was a dirty Rosian dog.”

Henry dared not look at his wife or he would have disgraced himself by bursting into laughter. Nurse was standing by, looking grim, and he recalled a rainy after noon when she had caught him and Alan and young Master Hal playing “pirate” in the nursery.

He explained to his son that the Rosians were now their friends and that it was not polite to refer to anyone by such a derogatory appellation as “dirty Rosian dog.”

Hal listened to the lecture with wide, solemn eyes and then said, “Can I have my sword back, Papa? Nurse took it away from me.”

“I think the sword should remain with Nurse for a time,” Henry said, trying to sound severe and prob ably failing, for his wife’s lips were twitching.

Young Master Hal gave a philosophical shrug. “That’s all right, Papa. Captain Alan promised next time he’d bring me a pistol.”

“My dear!” exclaimed his wife, casting Henry a look of alarm, while Nurse’s eyebrows shot up to the edge of her white cap. Henry would have to speak to Alan. Meanwhile, he deci ded it was time for diversionary tactics.

“Would you like one of these little tea cakes, son,” said Henry, presenting Hal with a treat from the tea cart.

This indulgence proved too much for Nurse, who advanced to rescue her charge. Seeing her coming, Hal crammed the small cake into his mouth before she could snatch it away.

“Such rich food before bed will give him nightmares, Your Lordship. Now, Master Henry, tell your mama and papa good night.”

Hal presented his mother with a sugary kiss, and Nurse carried him off, scattering crumbs and waving to his father over her shoulder.

Once Henry was certain his son could not hear, he threw back his head and roared with laughter.

“Dirty Rosian dog! Ha-ha! Wait until I tell Alan!”

“I am glad to see you more cheerful, my love,” said Ann.

“I must either laugh or break down and cry,” Henry replied, chuckling and wiping his eyes.

He picked up the newspaper, took one look at the hysterical headline ranting over the succession, and threw the paper to the floor. Flinging himself into his chair, he closed his eyes with a sigh.

Ann laid down her embroidery and came over to sit in his lap, resting her head on his shoulder. He put his arm around her and drew her close.

“Aren’t you afraid the servants will see us?” Henry asked. “A husband and wife aren’t supposed to be in love—at least not with each other.”

“The servants won’t come until I ring to take the tea tray,” Ann replied. She patted her belly. “And as for showing that I love you, I’m afraid we have let that par tic u lar cat out of the bag.”

Henry smiled, but his smile didn’t last. “I am glad to have a chance to talk. I have been thinking of giving Her Majesty my resignation.”

“Henry!” Ann sat up straight to stare at him. “You’re not serious!”

“I am very serious, my dear,” Henry replied.“We could move away from the city with its plagues and bad air and assassins, retire to our country estate in Staffordshire. You could go about the tenants with a little basket, doing good works. I could be a country squire and raise prize hogs. I think I would like that. Pigs are quite intelligent creatures. Far smarter than humans.”

“There, I knew you weren’t serious,” said Ann, snuggling back down with him.

“I am, though not perhaps about the hogs. I am serious about a life where I could be home with my family at night. Hal could run about the lawn with a huge, slobbering dog. Our daughter will have her own pony to ride.”

“First, we do not know that we are having a daughter. Second, our country house also came under attack from assassins, which makes the country just as dangerous as the city. Third, you would die of boredom and leave me a widow.”

Henry shook his head, not convinced. Ann smoothed the frown lines from his brow with her fingers. “Tell me what this is about, Henry. Is my aunt being more difficult than usual?”

“I have been trying to talk to Her Majesty about the line of the succession,” said Henry. “She must make her wishes known, although I fear her silence on the subject is partly my fault. When she did finally deign to discuss it with me, she hinted that she was thinking of naming her younger sister, Elinor, her successor. I was so shocked she would even consider that horrible woman that I may have overreacted.”

“I know I am also on the list,” said Ann. “But I always forget exactly where. Far down, I hope.”

“Very far down,” said Henry. “Your father and his brother are sons of the late King Godfrey, which makes them Mary’s half brothers. But they both carry the ‘bar sinister’ so they can’t inherit. Damn Godfrey and his philandering. This is all his fault. And to think I saved his life when I was young!”

“Godfrey was hopelessly in love with Lady Honoria, so my father always told me,” said Ann. “She was the love of his life.”

“Godfrey was fortunate the lady was married and that her husband was a fool. As it was, he had to pay an enormous sum to hush up the scandal. I’ve always stated love was the ruin of a man,” Henry added, shaking his head in mock sorrow.

Ann punished him by kissing him on his long nose and then slid off his lap. Returning decorously to her chair, she rang for the servants to remove the tea tray. After the servants left, Henry drew his chair close to hers to continue their conversation, while Ann took up her embroidery.

“Godfrey made matters worse by claiming your father and his brother as his sons,” said Henry. “He gave them titles, land, et cetera. Your uncle, Hugh, expected the throne and he was furious when Godfrey named his legitimate daughter, your aunt, as his heir.”

“My father said Godfrey couldn’t do anything else,” said Ann. “Mary had the support of the most power ful nobles. He and Hugh did not.”

Henry was silent, remembering. Seventeen years ago, he had been the one to make certain Mary had the support of the key members of the House of Nobles. He had been the one to make it clear to the dying Godfrey that in order to ensure the stability of the realm, he had to name Mary, not his bastard son, as his heir.

Henry had been twenty-eight years old then and he had discovered the power of secrets. He had learned how to ferret them out, how to keep them, how to use them to his advantage and the advantage of those whom he served.

Henry had ostensibly worked in the Foreign Office. His true job was spymaster to the king. Ever since he and his friends had helped thwart an assassination attempt against Godfrey when he was crown prince, Henry had handled vari ous matters of a delicate nature, including concealing Godfrey’s secret liaisons with his mistress, Lady Honoria.

Godfrey had ruled only a few years when the physicians told the king that there was nothing more they could do to treat the malignant growth in his stomach and that he had only weeks to live. Henry had coolly considered where to place his allegiance. He could have aligned himself with the bastard, Hugh, and his faction, for Henry knew that Godfrey wanted to name his son as his heir. Or Henry could side with Princess Mary.

Henry recalled discussing the matter with Alan, Simon, and Randolph.

“My loyalty is first and foremost to Freya,” Henry had told them.“Mary is the legitimate heir. Hugh is a bastard. If Godfrey were to name Hugh his heir, we would be embroiled in civil war. Our enemies would like nothing better.”

Ann nudged his foot with her own.

“My dear, you have wandered off and left me,” she said.

Henry smiled. “Sorry, my love. I was woolgathering.”

“I was saying that it was too bad my father is the younger son. He would make a good king,” said Ann.

“He would, in fact,” said Henry. “Sadly, your father would never consider it. Jeffrey is devoted to the Reformed Church and he has enough to do as bishop, trying to save the Church from the scandal following the war and the growing popularity of the Fundamentalists.”

“Why don’t you like Uncle Hugh? He is a good man, I believe,” said Ann, frowning over her embroidery, counting her stitches. “Is it because he’s an ironmonger or something like that?”

“An ironmonger sells kettles and horse shoes. Your uncle owns a coal mine and a steel mill,” Henry said. “I have no objection to his occupation. I don’t like him because he is brash and insolent and has radical ideas, such as abolishing the House of Nobles—”

“No! Truly?” Ann regarded him with consternation.

“That said, I may be forced to support him,” said Henry, adding with a grimace, “I prefer Hugh to the devout Elinor and her Rosian husband. I can manage Hugh. I could do nothing with Elinor.”

“My aunt will never agree to name Hugh her heir,” said Ann, shaking her head. “She dislikes him and my father.”

“Mary and her sister never forgave them for being born,” said Henry drily. “I suppose that is natural. Godfrey made it clear he loved his bastard sons more than he did his legitimate daughters. Poor Godfrey. He may have been a good king, but he was not a very good man.”

Ann was shocked. “Henry, don’t say such things. It’s… sacrilegious. Godfrey was God’s anointed.”

Henry wisely kept silent. Ann had been raised in a pious house hold, her father being the Bishop of Freya. He had taught his children to believe that monarchs derived the right to rule directly from God and therefore were subject to no authority except God’s.

Henry did not believe in the divine right of kings, but he did believe that a strong monarchy overseen by the nobility was the best form of government. He had witnessed firsthand the chaos that resulted when ordinary citizens, such as Frau Aalder, tried to rule a nation.

Ann was regarding him with an anxious air, undoubtedly convinced he was going straight to hell. Henry assumed he prob ably was, but he doubted it would be for thinking that kings and queens were human, could make mistakes like other mortals.

Knowing he had upset his wife, Henry looked for some way to make amends. He reached into her work basket and drew out a folded section of the Haever Gazette he had noticed hidden under several skeins of yarn.

“Ah, now I understand,” said Henry, indicating the article on the fold. “My wife is no doubt going to advance the claims of the dashing Prince Tom who believes himself to be divinely chosen to rule Freya.”

“I would do no such thing, Henry!” Ann protested. “How can you think that of me? This Prince Tom comes from a family of traitors. His forebearer James stole poor King Oswald’s throne, then murdered him and his sons!”

“King Oswald’s own claim to the throne was not the strongest,” Henry reflected. “His grand father, Oswald the First, stole the throne from his older half brother, Frederick— the true and rightful king. Oswald did not murder his half brother, but he did lock him up in some godforsaken castle for the rest of his life. Thus, I suppose one could say Oswald the First began this trou ble by deposing an anointed king. Perhaps God is punishing us by sending us Prince Tom.”

His wife lowered her embroidery to her lap and turned to her husband with a troubled look. Seeing him grinning, she relaxed. “Henry, you have been teasing me.”

“Just a trifle, my dear,” he admitted. “But if you don’t approve of Prince Tom, why have you been reading about him?”

“Not him,” said Ann. Blushing deeply, she took the paper and turned it over to indicate another story on the other side. “I have been reading ‘The Adventures of Captain Kate and Her Dragon Corsairs.’ ”

“Subtitled ‘The Tales of a Female Buccaneer’ by Miss Amelia Nettle-ship,” said Henry, glancing at the story with a smile.

“Kate has such wonderful adventures, Henry, and she is so bold and free and not afraid of anything,” said Ann, her eyes shining with enthusiasm. “Lady Rebecca introduced me to the stories. All my friends talk about Captain Kate far more than Prince Tom.”

Henry read a passage aloud. “‘Captain Kate shook back her beautiful mass of shimmering gold hair, drew her cutlass and leaped onto the deck of the Rosian warship. Pointing her cutlass at the throat of the cowering Rosian captain, she shouted,“Surrender or die, you scurvy dog!”’ ”

Henry shook his head in mock sorrow. “I see how it is. The day will come when Nurse will be devastated to inform me that my wife stabbed Polly with a sword and ran off to become a pirate.”

“A corsair, my dear,” said Ann. “‘Captain Kate and Her Dragon Corsairs.’ Kate is a real person and her adventures are true. She lives in the Aligoes. I wonder if Captain Northrop knows her? I will have to ask him the next time he visits.”

“And Alan and I are blamed for being a bad influence on our son!” Henry said, heaving a deep sigh.

“I will make you a bargain, Henry,” said Ann. “I will not run away to be a pirate if you will not resign. My aunt needs you.”

“No prize hogs?” Henry asked.

“No hogs of any sort,” said Ann firmly.

“Very well, my dear,” said Henry. “I will not resign. And you will not join Captain Kate’s bloodthirsty crew.”

Ann laughed. She looked so charming when she laughed that Henry was obliged to kiss her, and for a time he was able to forget about the cares of state.

He kept the newspaper, however, folding it and tucking it into his coat pocket when Ann wasn’t looking. She had given him an idea.

Excerpted from Spymaster Copyright © 2017 by Margaret Weis and Robert Krammes