A space opera adventure set in a distant future where an undercover agent has to go behind enemy lines to recover a lost ship and a possible traitor.

For Sonya Taaffe

When Shuos Jedao walked into his temporary quarters on Station Muru 5 and spotted the box, he assumed someone was attempting to assassinate him. It had happened before. Considering his first career, there was even a certain justice to it.

He ducked back around the doorway, although even with his reflexes, he would have been too late if it’d been a proper bomb. The air currents in the room would have wafted his biochemical signature to the box and caused it to trigger. Or someone could have set up the bomb to go off as soon as the door opened, regardless of who stepped in. Or something even less sophisticated.

Jedao retreated back down the hallway and waited one minute. Two. Nothing.

It could just be a package, he thought—paperwork that he had forgotten?—but old habits died hard.

He entered again and approached the desk, light-footed. The box, made of eye-searing green plastic, stood out against the bland earth tones of the walls and desk. It measured approximately half a meter in all directions. Its nearest face prominently displayed the gold seal that indicated that station security had cleared it. He didn’t trust it for a moment. Spoofing a seal wasn’t that difficult. He’d done it himself.

He inspected the box’s other visible sides without touching it, then spotted a letter pouch affixed to one side and froze. He recognized the handwriting. The address was written in spidery high language, while the name of the recipient—one Garach Jedao Shkan—was written both in the high language and his birth tongue, Shparoi, for good measure.

Oh, Mom, Jedao thought. No one else called him by that name anymore, not even the rest of his family. More important, how had his mother gotten his address? He’d just received his transfer orders last week, and he hadn’t written home about it because his mission was classified. He had no idea what his new general wanted him to do; she would tell him tomorrow morning when he reported in.

Jedao opened the box, which released a puff of cold air. Inside rested a tub labeled KEEP REFRIGERATED in both the high language and Shparoi. The tub itself contained a pale, waxy-looking solid substance. Is this what I think it is?

Time for the letter:

Hello, Jedao!

Congratulations on your promotion. I hope you enjoy your new command moth and that it has a more pronounceable name than the last one.

One: What promotion? Did she know something he didn’t? (Scratch that question. She always knew something he didn’t.) Two: Trust his mother to rate warmoths not by their armaments or the efficacy of their stardrives but by their names. Then again, she’d made no secret that she’d hoped he’d wind up a musician like his sire. It had not helped when he pointed out that when he attempted to sing in academy, his fellow cadets had threatened to dump grapefruit soup over his head.

Since I expect your eating options will be dismal, I have sent you goose fat rendered from the great-great-great-etc.-grandgosling of your pet goose when you were a child. (She was delicious, by the way.) Let me know if you run out and I’ll send more.

Love,

Mom

So the tub contained goose fat, after all. Jedao had never figured out why his mother sent food items when her idea of cooking was to gussy up instant noodles with an egg and some chopped green onions. All the cooking Jedao knew, he had learned either from his older brother or, on occasion, those of his mother’s research assistants who took pity on her kids.

What am I supposed to do with this? he wondered. As a cadet he could have based a prank around it. But as a warmoth commander he had standards to uphold.

More importantly, how could he compose a suitably filial letter of appreciation without, foxes forbid, encouraging her to escalate? (Baked goods: fine. Goose fat: less fine.) Especially when she wasn’t supposed to know he was here in the first place? Some people’s families sent them care packages of useful things, like liquor, pornography, or really nice cosmetics. Just his luck.

At least the mission gave him an excuse to delay writing back until his location was unclassified, even if she knew it anyway.

Jedao had heard a number of rumors about his new commanding officer, Brigadier General Kel Essier. Some of them, like the ones about her junior wife’s lovers, were none of his business. Others, like Essier’s taste in plum wine, weren’t relevant, but could come in handy if he needed to scare up a bribe someday. What had really caught his notice was her service record. She had fewer decorations than anyone else who’d served at her rank for a comparable period of time.

Either Essier was a political appointee—the Kel military denied the practice, but everyone knew better—or she was sitting on a cache of classified medals. Jedao had a number of those himself. (Did his mother know about those too?) Although Station Muru 5 was a secondary military base, Jedao had his suspicions about any “secondary” base that had a general in residence, even temporarily. That, or Essier was disgraced and Kel Command couldn’t think of anywhere else to dump her.

Jedao had a standard method for dealing with new commanders, which was to research them as if he planned to assassinate them. Needless to say, he never expressed it in those terms to his comrades.

He’d come up with two promising ways to get rid of Essier. First, she collected meditation foci made of staggeringly luxurious materials. One of her officers had let slip that her latest obsession was antique lacquerware. Planting a bomb or toxin in a collector-grade item wouldn’t be risky so much as expensive. He’d spent a couple hours last night brainstorming ways to steal one, just for the hell of it; lucky that he didn’t have to follow through.

The other method took advantage of the poorly planned location of the firing range on this level relative to the general’s office, and involved shooting her through several walls and a door with a high-powered rifle and burrower ammunition. Jedao hated burrower ammunition, not because it didn’t work but because it did. He had a lot of ugly scars on his torso from the time a burrower had almost killed him. That being said, he also believed in using the appropriate tool for the job.

No one had upgraded Muru 5 for the past few decades. Its computer grid ran on outdated hardware, making it easy for him to pull copies of all the maps he pleased. He’d also hacked into the security cameras long enough to check the layout of the general’s office. The setup made him despair of the architects who had designed the whole wretched thing. On top of that, Essier had set up her desk so a visitor would see it framed beautifully by the doorway, with her chair perfectly centered. Great for impressing visitors, less great for making yourself a difficult target. Then again, attending to Essier’s safety wasn’t his job.

Jedao showed up at Essier’s office seven minutes before the appointed time. “Whiskey?” said her aide.

If only, Jedao thought; he recognized it as one he couldn’t afford. “No, thank you,” he said with the appropriate amount of regret. He didn’t trust special treatment.

“Your loss,” said the aide. After another two minutes, she checked her slate. “Go on in. The general is waiting for you.”

As Jedao had predicted, General Essier sat dead center behind her desk, framed by the doorway and two statuettes on either side of the desk, gilded ash-hawks carved from onyx. Essier had dark skin and close-shaven hair, and the height and fine-spun bones of someone who had grown up in low gravity. The black-and-gold Kel uniform suited her. Her gloved hands rested on the desk in perfect symmetry. Jedao bet she looked great in propaganda videos.

Jedao saluted, fist to shoulder. “Commander Shuos Jedao reporting as ordered, sir.”

“Have a seat,” Essier said. He did. “You’re wondering why you don’t have a warmoth assignment yet.”

“The thought had crossed my mind, yes.”

Essier smiled. The smile was like the rest of her: beautiful and calculated and not a little deadly. “I have good news and bad news for you, Commander. The good news is that you’re due a promotion.”

Jedao’s first reaction was not gratitude or pride, but How did my mother—? Fortunately, a lifetime of How did my mother—? enabled him to keep his expression smooth and instead say, “And the bad news?”

“Is it true what they say about your battle record?”

This always came up. “You have my profile.”

“You’re good at winning.”

“I wasn’t under the impression that the Kel military found this objectionable, sir.”

“Quite right,” she said. “The situation is this. I have a mission in mind for you, but it will take advantage of your unique background.”

“Unique background” was a euphemism for We don’t have many commanders who can double as emergency special forces. Most Kel with training in special ops stayed in the infantry instead of seeking command in the space forces. Jedao made an inquiring noise.

“Perform well, and you’ll be given the fangmoth Sieve of Glass, which heads my third tactical group.”

A bribe, albeit one that might cause trouble. Essier had six tactical groups. A newly minted group tactical commander being assigned third instead of sixth? Had she had a problem with her former third-position commander?

“My former third took early retirement,” Essier said in answer to his unspoken question. “They were caught with a small collection of trophies.”

“Let me guess,” Jedao said. “Trophies taken from heretics.”

“Just so. Third tactical is badly shaken. Fourth has excellent rapport with her group and I don’t want to promote her out of it. But it’s an opportunity for you.”

“And the mission?”

Essier leaned back. “You attended Shuos Academy with Shuos Meng.”

“I did,” Jedao said. They’d gone by Zhei Meng as a cadet. “We’ve been in touch on and off.” Meng had joined a marriage some years back. Jedao had commissioned a painting of five foxes, one for each person in the marriage, and sent it along with his best wishes. Meng wrote regularly about their kids—they couldn’t be made to shut up about them—and Jedao sent gifts on cue, everything from hand-bound volumes of Kel jokes to fancy gardening tools. (At least they’d been sold to him as gardening tools. They looked suspiciously like they could double for heavy-duty surgical work.) “Why, what has Meng been up to?”

“Under the name Ahun Gerav, they’ve been in command of the merchanter Moonsweet Blossom.”

Jedao cocked an eyebrow at Essier. “That’s not a Shuos vessel.” It did, however, sound like an Andan one. The Andan faction liked naming their trademoths after flowers. “By ‘merchanter’ do you mean ‘spy’?”

“Yes,” Essier said with charming directness. “Twenty-six days ago, one of the Blossom’s crew sent a code red to Shuos Intelligence. This is all she was able to tell us.”

Essier retrieved a slate from within the desk and tilted it to show him a video. She needn’t have bothered with the visuals; the combination of poor lighting, camera jitter, and static made them impossible to interpret. The audio was little better: “. . . Blossom, code red to Overwatch . . . Gerav’s in . . .” Frustratingly, the static made the next few words unintelligible. “Du Station. You’d better—” The report of a gun, then another, then silence.

“Your task is to investigate the situation at Du Station in the Gwa Reality, and see if the crew and any of the intelligence they’ve gathered can be recovered. The Shuos heptarch suggested that you would be an ideal candidate for the mission. Kel Command was amenable.”

I just bet, Jedao thought. He had once worked directly under his heptarch, and while he’d been one of her better assassins, he didn’t miss those days. “Is this the only incident with the Gwa Reality that has taken place recently, or are there others?”

“The Gwa-an are approaching one of their regularly scheduled regime upheavals,” Essier said. “According to the diplomats, there’s a good chance that the next elected government will be less amenable to heptarchate interests. We want to go in, uncover what happened, and get out before things turn topsy-turvy.”

“All right,” Jedao said, “so taking a warmoth in would be inflammatory. What resources will I have instead?”

“Well, that’s the bad news,” Essier said, entirely too cheerfully. “Tell me, Commander, have you ever wanted to own a merchant troop?”

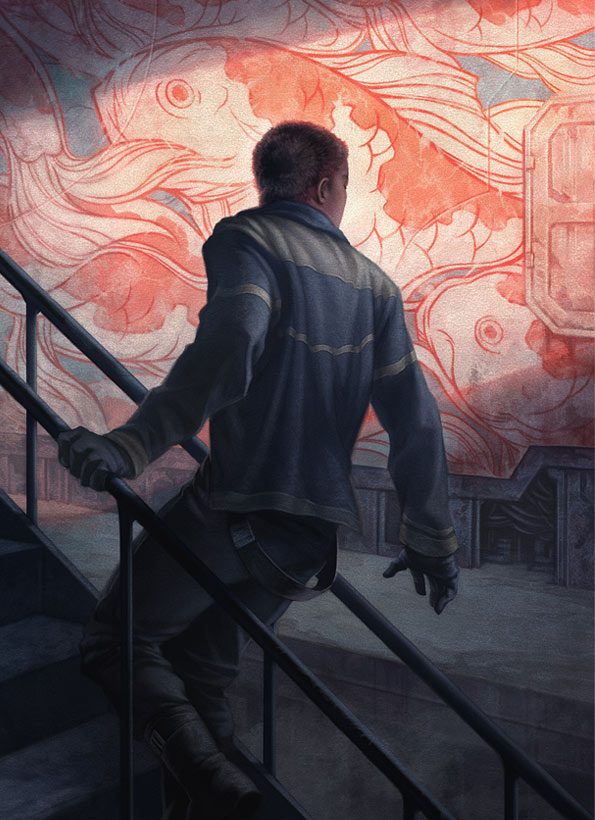

The troop consisted of eight trademoths, named Carp 1 to Carp 4, then Carp 7 to Carp 10. They occupied one of the station’s docking bays. Someone had painted each vessel with distended carp-figures in orange and white. It did not improve their appearance.

The usual commander of the troop introduced herself as Churioi Haval, not her real name. She was portly, had a squint, and wore gaudy gilt jewelry, all excellent ways to convince people that she was an ordinary merchant and not, say, Kel special ops. It hadn’t escaped his attention that she frowned ever so slightly when she spotted his sidearm, a Patterner 52, which wasn’t standard Kel issue. “You’re not bringing that, are you?” she said.

“No, I’d hate to lose it on the other side of the border,” Jedao said. “Besides, I don’t have a plausible explanation for why a boring communications tech is running around with a Shuos handgun.”

“I could always hold on to it for you.”

Jedao wondered if he’d ever get the Patterner back if he took her up on the offer. It hadn’t come cheap. “That’s kind of you, but I’ll have the station store it for me. By the way, what happened to Carp 5 and 6?”

“Beats me,” Haval said. “Before my time. The Gwa-an authorities have never hassled us about it. They’re already used to, paraphrase, ‘odd heptarchate numerological superstitions.’” She eyed Jedao critically, which made her look squintier. “Begging your pardon, but do you have undercover experience?”

What a refreshing question. Everyone knew the Shuos for their spies, saboteurs, and assassins, even though the analysts, administrators, and cryptologists did most of the real work. (One of his instructors had explained that “You will spend hours in front of a terminal developing posture problems” was far less effective at recruiting potential cadets than “Join the Shuos for an exciting future as a secret agent, assuming your classmates don’t kill you before you graduate.”) Most people who met Jedao assumed he’d killed an improbable number of people as Shuos infantry. Never mind that he’d been responsible for far more deaths since joining the regular military.

“You’d be surprised at the things I know how to do,” Jedao said.

“Well, I hope you’re good with cover identities,” Haval said. “No offense, but you have a distinctive name.”

That was a tactful way of saying that the Kel didn’t tolerate many Shuos line officers; most Shuos seconded to the Kel worked in Intelligence. Jedao had a reputation for, as one of his former aides had put it, being expendable enough to send into no-win situations but too stubborn to die. Jedao smiled at Haval and said, “I have a good memory.”

The rest of his crew also had civilian cover names. A tall, muscular man strolled up to them. Jedao surreptitiously admired him. The gold-mesh tattoo over the right side of his face contrasted handsomely with his dark skin. Too bad he was almost certainly Kel and therefore off-limits.

“This is Rhi Teshet,” Haval said. “When he isn’t watching horrible melodramas—”

“You have no sense of culture,” Teshet said.

“—he’s the lieutenant colonel in charge of our infantry.”

Damn. Definitely Kel, then, and in his chain of command, at that. “A pleasure, Colonel,” Jedao said.

Teshet’s returning smile was slow and wicked and completely unprofessional. “Get out of the habit of using ranks,” he said. “Just Teshet, please. I hear you like whiskey?”

Off-limits, Jedao reminded himself, despite the quickening of his pulse. Best to be direct. “I’d rather not get you in trouble.”

Haval was looking to the side with a where-have-I-seen-this-dance-before expression. Teshet laughed. “The fastest way to get us caught is to behave like you have the Kel code of conduct tattooed across your forehead. Whereas no one will suspect you of being a hotshot commander if you’re sleeping with one of your crew.”

“I don’t fuck people deadlier than I am, sorry,” Jedao said demurely.

“Wrong answer,” Haval said, still not looking at either of them. “Now he’s going to think of you as a challenge.”

“Also, I know your reputation,” Teshet said to Jedao. “Your kill count has got to be higher than mine by an order of magnitude.”

Jedao ignored that. “How often do you make trade runs into the Gwa Reality?”

“Two or three times a year,” Haval said. “The majority of the runs are to maintain the fiction. The question is, do you have a plan?”

He didn’t blame her for her skepticism. “Tell me again how much cargo space we have.”

Haval told him.

“We sometimes take approved cultural goods,” Teshet said, “in a data storage format negotiated during the Second Treaty of—”

“Don’t bore him,” Haval said. “The ‘trade’ is our job. He’s just here for the explode-y bits.”

“No, I’m interested,” Jedao said. “The Second Treaty of Mwe Enh, am I right?”

Haval blinked. “You have remarkably good pronunciation. Most people can’t manage the tones. Do you speak Tlen Gwa?”

“Regrettably not. I’m only fluent in four languages, and that’s not one of them.” Of the four, Shparoi was only spoken on his birth planet, making it useless for career purposes.

“If you have some Shuos notion of sneaking in a virus amid all the lectures on flower-arranging and the dueling tournament videos and the plays, forget it,” Teshet said. “Their operating systems are so different from ours that you’d have better luck getting a magpie and a turnip to have a baby.”

“Oh, not at all,” Jedao said. “How odd would it look if you brought in a shipment of goose fat?”

Haval’s mouth opened, closed.

Teshet said, “Excuse me?”

“Not literally goose fat,” Jedao conceded. “I don’t have enough for that and I don’t imagine the novelty would enable you to run a sufficient profit. I assume you have to at least appear to be trying to make a profit.”

“They like real profits even better,” Haval said.

Diverted, Teshet said, “You have goose fat? Whatever for?”

“Long story,” Jedao said. “But instead of goose fat, I’d like to run some of that variable-coefficient lubricant.”

Haval rubbed her chin. “I don’t think you could get approval to trade the formula or the associated manufacturing processes.”

“Not that,” Jedao said. “Actual canisters of lubricant. Is there someone in the Gwa Reality on the way to our luckless Shuos friend who might be willing to pay for it?”

Haval and Teshet exchanged baffled glances. Jedao could tell what they were thinking: Are we the victims of some weird bet our commander has going on the side? “There’s no need to get creative,” Haval said in a commendably diplomatic voice. “Cultural goods are quite reliable.”

You think this is creativity, Jedao thought. “It’s not that. Two battles ago, my fangmoth was almost blown in two because our antimissile defenses glitched. If we hadn’t used the lubricant as a stopgap sealant, we wouldn’t have made it.” That much was even true. “If you can’t offload all of it, I’ll find another use for it.”

“You do know you can’t cook with lubricant?” Teshet said. “Although I wonder if it’s good for—”

Haval stomped on his toe. “You already have plenty of the medically approved stuff,” she said crushingly, “no need to risk getting your private parts cemented into place.”

“Hey,” Teshet said, “you never know when you’ll need to improvise.”

Jedao was getting the impression that Essier had not assigned him the best of her undercover teams. Certainly they were the least disciplined Kel he’d run into in a while, but he supposed long periods undercover had made them more casual about regulations. No matter, he’d been dealt worse hands. “I’ve let you know what I want done, and I’ve already checked that the station has enough lubricant to supply us. Make it happen.”

“If you insist,” Haval said. “Meanwhile, don’t forget to get your immunizations.”

“Will do,” Jedao said, and strode off to Medical.

Jedao spent the first part of the voyage alternately learning basic Tlen Gwa, memorizing his cover identity, and studying up on the Gwa Reality. The Tlen Gwa course suffered some oddities. He couldn’t see the use of some of the vocabulary items, like the one for “navel.” But he couldn’t manage to unlearn it, either, so there it was, taking up space in his brain.

As for the cover identity, he’d had better ones, but he supposed the Kel could only do so much on short notice. He was now Arioi Sren, one of Haval’s distant cousins by marriage. He had three spouses, with whom he had quarreled recently over a point of interior decoration. “I don’t know anything about interior decoration,” Jedao had said, to which Haval retorted, “That’s probably what caused the argument.”

The documents had included loving photographs of the home in question, an apartment in a dome city floating in the upper reaches of a very pretty gas giant. Jedao had memorized the details before destroying them. While he couldn’t say how well the decor coordinated, he was good at layouts and kill zones. In any case, Sren was on “vacation” to escape the squabbling. Teshet had suggested that a guilt-inducing affair would round out the cover identity. Jedao said he’d think about it.

Jedao was using spray-on temporary skin, plus a high-collared shirt, to conceal multiple scars, including the wide one at the base of his neck. The temporary skin itched, which couldn’t be helped. He hoped no one would strip-search him, but in case someone did, he didn’t want to have to explain his old gunshot wounds. Teshet had also suggested that he stop shaving—the Kel disliked beards—but Jedao could only deal with so much itching.

The hardest part was not the daily skinseal regimen, but getting used to wearing civilian clothes. The Kel uniform included gloves, and Jedao felt exposed going around with naked hands. But keeping his gloves would have been a dead giveaway, so he’d just have to live with it.

The Gwa-an fascinated him most of all. Heptarchate diplomats called their realm the Gwa Reality. Linguists differed on just what the word rendered as “Reality” meant. The majority agreed that it referred to the Gwa-an belief that all dreams took place in the same noosphere, connecting the dreamers, and that even inanimate objects dreamed.

Gwa-an protocols permitted traders to dock at designated stations. Haval quizzed Jedao endlessly on the relevant etiquette. Most of it consisted of keeping his mouth shut and letting Haval talk, which suited him fine. While the Gwa-an provided interpreters, Haval said cultural differences were the real problem. “Above all,” she added, “if anyone challenges you to a duel, don’t. Just don’t. Look blank and plead ignorance.”

“Duel?” Jedao said, interested.

“I knew we were going to have to have this conversation,” Haval said glumly. “They don’t use swords, so get that idea out of your head.”

“I didn’t bring my dueling sword anyway, and Sren wouldn’t know how,” Jedao said. “Guns?”

“Oh no,” she said. “They use pathogens. Designer pathogens. Besides the fact that their duels can go on for years, I’ve never heard that you had a clue about genetic engineering.”

“No,” Jedao said, “that would be my mother.” Maybe next time he could suggest to Essier that his mother be sent in his place. His mother would adore the chance to talk shop. Of course, then he’d be out of a job. “Besides, I’d rather avoid bringing a plague back home.”

“They claim they have an excellent safety record.”

Of course they would. “How fast can they culture the things?”

“That was one of the things we were trying to gather data on.”

“If they’re good at diseasing up humans, they may be just as good at manufacturing critters that like to eat synthetics.”

“While true of their tech base in general,” Haval said, “they won’t have top-grade labs at Du Station.”

“Good to know,” Jedao said.

Jedao and Teshet also went over the intelligence on Du Station. “It’s nice that you’re taking a personal interest,” Teshet said, “but if you think we’re taking the place by storm, you’ve been watching too many dramas.”

“If Kel special forces aren’t up for it,” Jedao said, very dryly, “you could always send me. One of me won’t do much good, though.”

“Don’t be absurd,” Teshet said. “Essier would have my head if you got hurt. How many people have you assassinated?”

“Classified,” Jedao said.

Teshet gave a can’t-blame-me-for-trying shrug. “Not to say I wouldn’t love to see you in action, but it isn’t your job to run around doing the boring infantry work. How do you mean to get the crew out? Assuming they survived, which is a big if.”

Jedao tapped his slate and brought up the schematics for one of their cargo shuttles. “Five per trader,” he said musingly.

“Du Station won’t let us land the shuttles however we please.”

“Did I say anything about landing them?” Before Teshet could say anything further, Jedao added, “You might have to cross the hard way, with suits and webcord. How often have your people drilled that?”

“We’ve done plenty of extravehicular,” Teshet said, “but we’re going to need some form of cover.”

“I’m aware of that,” Jedao said. He brought up a calculator and did some figures. “That will do nicely.”

“Sren?”

Jedao grinned at Teshet. “I want those shuttles emptied out, everything but propulsion and navigation. Get rid of suits, seats, all of it.”

“Even life support?”

“Everything. And it’ll have to be done in the next seventeen days, so the Gwa-an can’t catch us at it.”

“What do we do with the innards?”

“Dump them. I’ll take full responsibility.”

Teshet’s eyes crinkled. “I knew I was going to like you.”

Uh-oh, Jedao thought, but he kept that to himself.

“What are you going to be doing?” Teshet asked.

“Going over the dossiers before we have to wipe them,” Jedao said. Meng’s in particular. He’d believed in Meng’s fundamental competence even back in academy, before they’d learned confidence in themselves. What had gone wrong?

Jedao had first met Shuos Meng (Zhei Meng, then) during an exercise at Shuos Academy. The instructor had assigned them to work together. Meng was chubby and had a vine-and-compass tattoo on the back of their left hand, identifying them as coming from a merchanter lineage.

That day, the class of twenty-nine cadets met not in the usual classroom but a windowless space with a metal table in the front and rows of two-person desks with benches that looked like they’d been scrubbed clean of graffiti multiple times. (“Wars come and go, but graffiti is forever,” as one of Jedao’s lovers liked to say.) Besides the door leading out into the hall, there were two other doors, neither of which had a sign indicating where they led. Tangles of pipes led up the walls and storage bins were piled beside them. Jedao had the impression that the room had been pressed into service at short notice.

Jedao and Meng sat at their assigned seats and hurriedly whispered introductions to each other while the instructor read off the rest of the pairs.

“Zhei Meng,” Jedao’s partner said. “I should warn you I barely passed the weapons qualifications. But I’m good with languages.” Then a quick grin: “And hacking. I figured you’d make a good partner.”

“Garach Jedao,” he said. “I can handle guns.” Understatement; he was third in the class in Weapons. And if Meng had, as they implied, shuffled the assignments, that meant they were one of the better hackers. “Why did you join up?”

“I want to have kids,” Meng said.

“Come again?”

“I want to marry into a rich lineage,” Meng said. “That means making myself more respectable. When the recruiters showed up, I said what the hell.”

The instructor smiled coolly at the two of them, and they shut up. She said, “If you’re here, it’s because you’ve indicated an interest in fieldwork. Like you, we want to find out if it’s something you have any aptitude for, and if not, what better use we can make of your skills.” You’d better have some skills went unsaid. “You may expect to be dropped off in the woods or some such nonsense. We don’t try to weed out first-years quite that early. No; this initial exercise will take place right here.”

The instructor’s smile widened. “There’s a photobomb in this room. It won’t cause any permanent damage, but if you don’t disarm it, you’re all going to be walking around wearing ridiculous dark lenses for a week. At least one cadet knows where the bomb is. If they keep its location a secret from the rest of you, they win. Of course, they’ll also go around with ridiculous dark lenses, but you can’t have everything. On the other hand, if someone can persuade that person to give up the secret, everyone wins. So to speak.”

The rows of cadets stared at her. Jedao leaned back in his chair and considered the situation. Like several others in the class, he had a riflery exam in three days and preferred to take it with undamaged vision.

“You have four hours,” the instructor said. “There’s one restroom.” She pointed to one of the doors. “I expect it to be in impeccable condition at the end of the four hours.” She put her slate down on the table at the head of the room. “Call me with this if you figure it out. Good luck.” With that, she walked out. The door whooshed shut behind her.

“We’re screwed,” Meng said. “Just because I’m in the top twenty on the leaderboard in Elite Thundersnake 900 doesn’t mean I could disarm real bombs if you yanked out my toenails.”

“Don’t give people ideas,” Jedao said. Meng didn’t appear to find the joke funny. “This is about people, not explosives.”

Two pairs of cadets had gotten up and were beginning a search of the room. A few were talking to each other in hushed, tense voices. Still others were looking around at their fellows with hard, suspicious eyes.

Meng said in Shparoi, “Do you know where the bomb is?”

Jedao blinked. He hadn’t expected anyone at the Academy to know his birth tongue. Of course, by speaking in an obscure low language, Meng was drawing attention to them. Jedao shook his head.

Meng looked around, hands bunching the fabric of their pants. “What do you recommend we do?”

In the high language, Jedao said, “You can do whatever you want.” He retrieved a deck of jeng-zai cards—he always had one in his pocket—and shuffled it. “Do you play?”

“You realize we’re being graded on this, right? Hell, they’ve got cameras on us. They’re watching the whole thing.”

“Exactly,” Jedao said. “I don’t see any point in panicking.”

“You’re out of your mind,” Meng said. They stood up, met the other cadets’ appraising stares, then sat down again. “Too bad hacking the instructor’s slate won’t get us anywhere. I doubt she left the answer key in an unencrypted file on it.”

Jedao gave Meng a quizzical look, wondering if there was anything more behind the remark—but no, Meng had put their chin in their hands and was brooding. If only you knew, Jedao thought, and dealt out a game of solitaire. It was going to be a very dull game, because he had stacked the deck, but he needed to focus on the people around him, not the game. The cards were just to give his hands something to do. He had considered taking up crochet, but thanks to an incident earlier in the term, crochet hooks, knitting needles, and fountain pens were no longer permitted in class. While this was a stupid restriction, considering that most of the cadets were learning unarmed combat, he wasn’t responsible for the administration’s foibles.

“Jedao,” Meng said, “maybe you’ve got high enough marks that you can blow off this exercise, but—”

Since I’m not blowing it off was unlikely to be believed, Jedao flipped over a card—three of Doors, just as he’d arranged—and smiled at Meng. So Meng had had their pick of partners and had chosen him? Well, he might as well do something to justify the other cadet’s faith in him. After all, despite their earlier remark, weapons weren’t the only things that Jedao was good at. “Do me a favor and we can get this sorted,” he said. “You want to win? I’ll show you winning.”

Now Jedao was attracting some of the hostile stares as well. Good. It took the heat off Meng, who didn’t seem to have a great tolerance for pressure. Stay out of wet work, he thought; but they could have that chat later. Or one of the instructors would.

Meng fidgeted; caught themselves. “Yeah?”

“Get me the slate.”

“You mean the instructor’s slate? You can’t possibly have figured it out already. Unless—” Meng’s eyes narrowed.

“Less thinking, more acting,” Jedao said, and got up to retrieve the slate himself.

A pair of cadets, a girl and a boy, blocked his way. “You know something,” said the girl. “Spill.” Jedao knew them from Analysis; the two were often paired there, too. The girl’s name was Noe Irin. The boy had five names and went by Veller. Jedao wondered if Veller wanted to join a faction so he could trim things down to a nice, compact, two-part name. Shuos Veller: much less of a mouthful. Then again, Jedao had a three-part name, also unusual, if less unwieldy, so he shouldn’t criticize.

“Just a hunch,” Jedao said.

Irin bared her teeth. “He always says it’s a hunch,” she said to no one in particular. “I hate that.”

“It was only twice,” Jedao said, which didn’t help his case. He backed away from the instructor’s desk and sat down, careful not to jostle the solitaire spread. “Take the slate apart. The photobomb’s there.”

Irin’s lip curled. “If this is one of your fucking clever tricks, Jay—”

Meng blinked at the nickname. “You two sleeping together, Jedao?” they asked, sotto voce.

Not sotto enough. “No,” Jedao and Irin said at the same time.

Veller ignored the byplay and went straight for the tablet, which he bent to without touching it. Jedao respected that. Veller had the physique of a tiger-wrestler (now there was someone he wouldn’t mind being caught in bed with), a broad face, and a habitually bland, dreamy expression. Jedao wasn’t fooled. Veller was almost as smart as Irin, had already been tracked into bomb disposal, and was less prone to flights of temper.

“Is there a tool closet in here?” Veller said. “I need a screwdriver.”

“You don’t carry your own anymore?” Jedao said.

“I told him he should,” Irin said, “but he said they were too similar to knitting needles. As if anyone in their right mind would knit with a pair of screwdrivers.”

“I think he meant that they’re stabby things that can be driven into people’s eyes,” Jedao said.

“I didn’t ask for your opinion, Jay.”

Jedao put his hands up in a conciliatory gesture and shut his mouth. He liked Irin and didn’t want to antagonize her any more than necessary. The last time they’d been paired together, they’d done quite well. She would come around; she just needed time to work through the implications of what the instructor had said. She was one of those people who preferred to think about things without being interrupted.

One of the other cadets wordlessly handed Veller a set of screwdrivers. Veller mumbled his thanks and got to work. The class watched, breathless.

“There,” Veller said at last. “See that there, all hooked in? Don’t know what the timer is, but there it is.”

“I find it very suspicious that you forfeited your chance to show up everyone else in this exercise,” Irin said to Jedao. “Is there anyone else who knew?”

“Irin,” Jedao said, “I don’t think the instructor told anyone where she’d left the photobomb. She just stuck it in the slate because that was the last place we’d look. The test was meant to reveal which of us would backstab the others, but honestly, that’s so counterproductive. I say we disarm the damn thing and skip to the end.”

Irin’s eyes crossed and her lips moved as she recited the instructor’s words under her breath. That was another thing Jedao liked about her. Irin had a great memory. Admittedly, that made it difficult to cheat her at cards, as he’d found out the hard way. He’d spent three hours doing her kitchen duties for her the one time he’d tried. He liked people who could beat him at cards. “It’s possible,” she said grudgingly after she’d reviewed the assignment’s instructions.

“Disarmed,” Veller said shortly after that. He pulled out the photobomb and left it on the desk, then set about reassembling the slate.

Jedao glanced over at Meng. For a moment, his partner’s expression had no anxiety in it, but a raptor’s intent focus. Interesting: What were they watching for?

“I hope I get a quiet posting at a desk somewhere,” Meng said.

“Then why’d you join up?” Irin said.

Jedao put his hand over Meng’s, even though he was sure that they had just lied. “Don’t mind her,” he said. “You’ll do fine.”

Meng nodded and smiled up at him.

Why do I have the feeling that I’m not remotely the most dangerous person in the room? Jedao thought. But he returned Meng’s smile, all the same. It never hurt to have allies.

A Gwa patrol ship greeted them as they neared Du Station. Haval had assured Jedao that this was standard practice and obligingly matched velocities.

Jedao listened in on Haval speaking with the Gwa authority, who spoke flawless high language. “They don’t call it ‘high language,’ of course,” Haval had explained to Jedao earlier. “They call it ‘mongrel language.’” Jedao had expressed that he didn’t care what they called it.

Haval didn’t trust Jedao to keep his mouth shut, so she’d stashed him in the business office with Teshet to keep an eye on him. Teshet had brought a wooden box that opened up to reveal an astonishing collection of jewelry. Jedao watched out of the corner of his eye as Teshet made himself comfortable in the largest chair, dumped the box’s contents on the desk, and began sorting it according to criteria known only to him.

Jedao was watching videos of the command center and the communications channel, and tried to concentrate on reading the authority’s body language, made difficult by her heavy zigzag cosmetics and the layers of robes that cloaked her figure. Meanwhile, Teshet put earrings, bracelets, and mysterious hooked and jeweled items in piles, and alternated helpful glosses of Gwa-an gestures with borderline insubordinate, not to say lewd, suggestions for things he could do with Jedao. Jedao was grateful that his ability to blush, like his ability to be tickled, had been burned out of him in Academy. Note to self: Suggest to General Essier that Teshet is wasted in special ops. Maybe reassign him to Recreation?

Jedao mentioned this to Teshet while Haval was discussing the cargo manifest with the authority. Teshet lowered his lashes and looked sideways at Jedao. “You don’t think I’m good at my job?” he asked.

“You have an excellent record,” Jedao said.

Teshet sighed, and his face became serious. “You’re used to regular Kel, I see.”

Jedao waited.

“I end up in a lot of situations where if people get the notion that I’m a Kel officer, I may end up locked up and tortured. While that could be fun in its own right, it makes career advancement difficult.”

“You could get a medal out of it.”

“Oh, is that how you got promoted so—”

Jedao held up his hand, and Teshet stopped. On the monitor, Haval was saying, in a greasy voice, “I’m glad to hear of your interest, madam. We would have been happy to start hauling the lubricant earlier, except we had to persuade our people that—”

The authority’s face grew even more imperturbable. “You had to figure out whom to bribe.”

“We understand there are fees—”

Jedao listened to Haval negotiating her bribe to the authority with half an ear. “Don’t tell me all that jewelry’s genuine?”

“The gems are mostly synthetics,” Teshet said. He held up a long earring with a rose quartz at the end. “No, this won’t do. I bought it for myself, but you’re too light-skinned for it to look good on you.”

“I’m wearing jewelry?”

“Unless you brought your own—scratch that, I bet everything you own is in red and gold.”

“Yes.” Red and gold were the Shuos faction colors.

Teshet tossed the rose quartz earring aside and selected a vivid emerald ear stud. “This will look nice on you.”

“I don’t get a say?”

“How much do you know about merchanter fashion trends out in this march?”

Jedao conceded the point.

The private line crackled to life. “You two still in there?” said Haval’s voice.

“Yes, what’s the issue?” Teshet said.

“They’re boarding us to check for contraband. You haven’t messed with the drugs cabinet, have you?”

Teshet made an affronted sound. “You thought I was going to get Sren high?”

“I don’t make assumptions when it comes to you, Teshet. Get the hell out of there.”

Teshet thrust the emerald ear stud and two bracelets at Jedao. “Put those on,” he said. “If anyone asks you where the third bracelet is, say you had to pawn it to make good on a gambling debt.”

Under other circumstances, Jedao would have found this offensive—he was good at gambling—but presumably Sren had different talents. As he put on the earring, he said, “What do I need to know about these drugs?”

Teshet was stuffing the rest of the jewelry back in the box. “Don’t look at me like that. They’re illegal both in the heptarchate and the Gwa Reality, but people run them anyway. They make useful cover. The Gwa-an search us for contraband, they find the contraband, they confiscate the contraband, we pay them a bribe to keep quiet about it, they go away happy.”

Impatient with Jedao fumbling with the clasp of the second bracelet, Teshet fastened it for him, then turned Jedao’s hand over and studied the scar at the base of his palm. “You should have skinsealed that one too, but never mind.”

“I’m bad at peeling vegetables?” Jedao suggested. Close enough to “knife fight,” right? And much easier to explain away than bullet scars.

“Are you two done?” Haval’s voice demanded.

“We’re coming, we’re coming,” Teshet said.

Jedao took up his post in the command center. Teshet himself disappeared in the direction of the airlock. Jedao wasn’t aware that anything had gone wrong until Haval returned to the command center, flanked by two personages in bright orange space suits. Both personages wielded guns of a type Jedao had never seen before, which made him irrationally happy. While most of his collection was at home with his mother, he relished adding new items. Teshet was nowhere in sight.

Haval’s pilot spoke before the intruders had a chance to say anything. “Commander, what’s going on?”

The broader of the two personages spoke in Tlen Gwa, then kicked Haval in the shin. “Guess what,” Haval said with a macabre grin. “Those aren’t the real authorities we ran into. They’re pirates.”

Oh, for the love of fox and hound, Jedao thought. In truth, he wasn’t surprised, just resigned. He never trusted it when an operation went too smoothly.

The broader personage spoke again. Haval sighed deeply, then said, “Hand over all weapons or they start shooting.”

Where’s Teshet? Jedao wondered. As if in answer, he heard a gunshot, then the ricochet. More gunshots. He was sure at least one of the shooters was Teshet or one of Teshet’s operatives: They carried Stinger 40s and he recognized the characteristic whine of the reports.

Presumably Teshet was occupied, which left matters here up to him. Some of Haval’s crew went armed. Jedao did not—they had agreed that Sren wouldn’t know how to use a gun—but that didn’t mean he wasn’t dangerous. While the other members of the crew set down their guns, Jedao flung himself at the narrower personage’s feet.

The pirates did not like this. But Jedao had always been blessed, or perhaps cursed, with extraordinarily quick reflexes. He dropped his weight on one arm and leg and kicked the narrow pirate’s feet from under them with the other leg. The narrow pirate discharged their gun. The bullet passed over Jedao and banged into one of the status displays, causing it to spark and sputter out. Haval yelped.

Jedao had already sprung back to his feet—damn the twinge in his knees, he should have that looked into—and twisted the gun out of the narrow pirate’s grip. The narrow pirate had the stunned expression that Jedao was used to seeing on people who did not deal with professionals very often. He shot them, but thanks to their loose-limbed flailing, the first bullet took them in the shoulder. The second one made an ugly hole in their forehead, and they dropped.

The broad pirate had more presence of mind, but chose the wrong target. Jedao smashed her wrist aside with the knife-edge of his hand just as she fired at Haval five times in rapid succession. Her hands trembled visibly. Four of the shots went wide. Haval had had the sense to duck, but Jedao smelled blood and suspected she’d been hit. Hopefully nowhere fatal.

Jedao shot the broad pirate in the side of the head just as she pivoted to target him next. Her pistol clattered to the floor as she dropped. By reflex he flung himself to the side in case it discharged, but it didn’t.

Once he had assured himself that both pirates were dead, he knelt at Haval’s side and checked the wound. She had been very lucky. The single bullet had gone through her side, missing the major organs. She started shouting at him for going up unarmed against people with guns.

“I’m getting the medical kit,” Jedao said, too loudly, to get her to shut up. His hands were utterly steady as he opened the cabinet containing the medical kit and brought it back to Haval, who at least had the good sense not to try to stand up.

Haval scowled, but accepted the painkiller tabs he handed her. She held still while he cut away her shirt and inspected the entry and exit wounds. At least the bullet wasn’t a burrower, or she wouldn’t have a lung anymore. He got to work with the sterilizer.

By the time Teshet and two other soldiers entered the command center, Jedao had sterilized and sealed the wounds. Teshet crossed the threshold with rapid strides. When Haval’s head came up, Teshet signed sharply for her to be quiet. Curious, Jedao also kept silent.

Teshet drew his combat knife, then knelt next to the larger corpse. With a deft stroke, he cut into the pirate’s neck, then yanked out a device and its wires. Blood dripped down and obscured the metal. He repeated the operation for the other corpse, then crushed both devices under his heel. “All right,” he said. “It should be safe to talk now.”

Jedao raised his eyebrows, inviting explanation.

“Not pirates,” Teshet said. “Those were Gwa-an special ops.”

Hmm. “Then odds are they were waiting for someone to show up to rescue the Moonsweet Blossom,” Jedao said.

“I don’t disagree.” Teshet glanced at Haval, then back at the corpses. “That wasn’t you, was it?”

Haval’s eyes were glazed, a side effect of the painkiller, but she wasn’t entirely out of it. “Idiot here risked his life. We could have handled it.”

“I wasn’t the one in danger,” Jedao said, remembering the pirates’ guns pointed at her. Haval might not be particularly respectful, as subordinates went, cover identity or not, but she was his subordinate, and he was responsible for her. To Teshet: “Your people?”

“Two down,” Teshet said grimly, and gave him the names. “They died bravely.”

“I’m sorry,” Jedao said; two more names to add to the long litany of those he’d lost. He was thinking about how to proceed, though. “The real Gwa-an patrols won’t be likely to know about this. It’s how I’d run the op—the fewer people who are aware of the truth, the better. I bet their orders are to take in any surviving ‘pirates’ for processing, and then the authorities will release and debrief the operatives from there. What do you normally do in case of actual pirates?”

“Report the incident,” Haval said. Her voice sounded thready. “Formal complaint if we’re feeling particularly annoying.”

“All right.” Jedao calmly began taking off the jewelry and his clothes. “That one’s about my size,” he said, nodding at the smaller of the two corpses. The suit would be tight across the shoulders, but that couldn’t be helped. “Congratulations, not two but three of your crew died heroically, but you captured a pirate in the process.”

Teshet made a wistful sound. “That temporary skin stuff obscures your musculature, you know.” But he helpfully began stripping the indicated corpse, then grabbed wipes to get rid of the blood on the suit.

“I’ll make it up to you some other time,” Jedao said recklessly. “Haval, make that formal complaint and demand that you want your captive tried appropriately. Since the nearest station is Du, that’ll get me inserted so I can investigate.”

“You’re just lucky some of the Gwa-an are as sallow as you are,” Haval said as Jedao changed clothes.

“I will be disappointed in you if you don’t have restraints,” Jedao said to Teshet.

Teshet’s eyes lit.

Jedao rummaged in the medical kit until he found the eye drops he was looking for. They were meant to counteract tear gas, but they had a side effect of pupil dilation, which was what interested him. It would help him feign concussion.

“We’re running short on time, so listen closely,” Jedao said. “Turn me over to the Gwa-an. Don’t worry about me; I can handle myself.”

“Je—Sren, I don’t care how much you’ve studied the station’s schematics, you’ll be outnumbered thousands to one on foreign territory.”

“Sometime over drinks I’ll tell you about the time I infiltrated a ring-city where I didn’t speak any of the local languages,” Jedao said. “Turn me in. I’ll locate the crew, spring them, and signal when I’m ready. You won’t be able to mistake it.”

Haval’s brow creased. Jedao kept speaking. “After you’ve done that, load all the shuttles full of lubricant canisters. Program the lubricant to go from zero-coefficient flow to harden completely in response to the radio signal. You’re going to put the shuttles on autopilot. When you see my signal, launch the shuttles’ contents toward the station’s turret levels. That should gum them up and buy us cover.”

“All our shuttles?” Haval said faintly.

“Haval,” Jedao said, “stop thinking about profit margins and repeat my orders back to me.”

She did.

“Splendid,” Jedao said. “Don’t disappoint me.”

The Gwa-an took Jedao into custody without comment. Jedao feigned concussion, saving him from having to sound coherent in a language he barely spoke. The Gwa-an official responsible for him looked concerned, which was considerate of him. Jedao hoped to avoid killing him or the guard. Only one guard, thankfully; they assumed he was too injured to be a threat.

The first thing Jedao noticed about the Gwa-an shuttle was how roomy it was, with wastefully widely spaced seats. He hadn’t noticed that the Gwa-an were, on average, that much larger than the heptarchate’s citizens. (Not that this said much. Both nations contained a staggering variety of ethnic groups and their associated phenotypes. Jedao himself was on the short side of average for a heptarchate manform.) At least being “concussed” meant he didn’t have to figure out how the hell the safety restraints worked, because while he could figure it out with enough fumbling, it would look damned suspicious that he didn’t already know. Instead, the official strapped him in while saying things in a soothing voice. The guard limited themselves to a scowl.

Instead of the smell of disinfectant that Jedao associated with shuttles, the Gwa-an shuttle was pervaded by a light, almost effervescent fragrance. He hoped it wasn’t intoxicating. Or rather, part of him hoped it was, because he didn’t often have good excuses to screw around with new and exciting recreational drugs, but it would impede his effectiveness. Maybe all Gwa-an disinfectants smelled this good? He should steal the formula. Voidmoth crews everywhere would thank him.

Even more unnervingly, the shuttle played music on the way to the station. At least, while it didn’t resemble any music he’d heard before, it had a recognizable beat and some sort of flute in it. From the others’ reactions, this was normal and possibly even boring. Too bad he was about as musical as a pair of boots.

The shuttle docked smoothly. Jedao affected not to know what was going on and allowed the official to chirp at him. Eventually a stretcher arrived and they put him on it. They emerged into the lights of the shuttle bay. Jedao’s temples twinged with the beginning of a headache. At least it meant the eye drops were still doing their job.

The journey to Du Station’s version of Medical took forever. Jedao was especially eager to escape based on what he’d learned of Gwa-an medical therapies, which involved too many genetically engineered critters for his comfort. (He had read up on the topic after Haval told him about the dueling.) He did consider that he could make his mother happy by stealing some pretty little microbes for her, but with his luck they’d turn his testicles inside out.

When the medic took him into an examination room, Jedao whipped up and felled her with a blow to the side of the neck. The guard was slow to react. Jedao grasped their throat and grappled with them, waiting the interminable seconds until they slumped, unconscious. He had a bad moment when he heard footsteps passing by. Luckily, the guard’s wheeze didn’t attract attention. Jedao wasn’t modest about his combat skills, but they wouldn’t save him if he was sufficiently outnumbered.

Too bad he couldn’t steal the guard’s uniform, but it wouldn’t fit him. So it would have to be the medic’s clothes. Good: the medic’s clothes were robes instead of something more form-fitting. Bad: even though the garments would fit him, more or less, they were in the style for women.

I will just have to improvise, Jedao thought. At least he’d kept up the habit of shaving, and the Gwa-an appeared to permit a variety of haircuts in all genders, so his short hair and bangs wouldn’t be too much of a problem. As long as he moved quickly and didn’t get stopped for conversation—

Jedao changed, then slipped out and took a few moments to observe how people walked and interacted so he could fit in more easily. The Gwa-an were terrible about eye contact and, interestingly for station-dwellers, preferred to keep each other at a distance. He could work with that.

His eyes still ached, since Du Station had abominably bright lighting, but he’d just have to prevent people from looking too closely at him. It helped that he had dark brown eyes to begin with, so the dilated pupils wouldn’t be obvious from a distance. He was walking briskly toward the lifts when he heard a raised voice. He kept walking. The voice called again, more insistently.

Damn. He turned around, hoping that someone hadn’t recognized his outfit from behind. A woman in extravagant layers of green, lilac, and pink spoke to him in strident tones. Jedao approached her rapidly, wincing at her voice, and hooked her into an embrace. Maybe he could take advantage of this yet.

“You’re not—” she began to say.

“I’m too busy,” he said over her, guessing at how best to deploy the Tlen Gwa phrases he knew. “I’ll see you for tea at thirteen. I like your coat.”

The woman’s face turned an ugly mottled red. “You like my what?” At least he thought he’d said “coat.” She stepped back from him, pulling what looked like a small perfume bottle from among her layers of clothes.

He tensed, not wanting to fight her in full view of passersby. She spritzed him with a moist vapor, then smiled coolly at him before spinning on her heel and walking away.

Shit. Just how fast-acting were Gwa-an duels, anyway? He missed the sensible kind with swords; his chances would have been much better. He hoped the symptoms wouldn’t be disabling, but then, the woman couldn’t possibly have had a chance to tailor the infectious agent to his system, and maybe the immunizations would keep him from falling over sick until he had found Meng and their crew.

How had he offended her, anyway? Had he gotten the word for “coat” wrong? Now that he thought about it, the word for “coat” differed from the word for “navel” only by its tones, and—hells and foxes, he’d messed up the tone sandhi, hadn’t he? He kept walking, hoping that she’d be content with getting him sick and wouldn’t call security on him.

At last he made it to the lifts. While stealing the medic’s uniform had also involved stealing their keycard, he preferred not to use it. Rather, he’d swapped the medic’s keycard for the loud woman’s. She had carried hers on a braided lanyard with a clip. It would do nicely if he had to garrote anyone in a hurry. The garrote wasn’t one of his specialties, but as his girlfriend the first year of Shuos Academy had always been telling him, it paid to keep your options open.

At least the lift’s controls were less perilous than figuring out how to correctly pronounce items of clothing. Jedao had by no means achieved reading fluency in Tlen Gwa, but the language had a wonderfully tidy writing system, with symbols representing syllables and odd little curlicue diacritics that changed what vowel you used. He had also theoretically memorized the numbers from 1 to 9,999. Fortunately, Du Station had fewer than 9,999 levels.

Two of the other people on the lift stared openly at Jedao. He fussed with his hair on the grounds that it would look like ordinary embarrassment and not Hello! I am a cross-dressing enemy agent, pleased to make your acquaintance. Come to that, Gwa-an women’s clothes were comfortable, and all the layers meant that he could, in principle, hide useful items like garrotes in them. He wondered if he could keep them as a souvenir. Start a fashion back home. He bet his mother would approve.

Intelligence had given him a good idea of where Meng and their crew might be held. At least, Jedao hoped that Du Station’s higher-ups hadn’t faked him out by stowing them in the lower-security cells as opposed to the top-security ones. He was betting a lot on the guess that the Gwa-an were still in the process of interrogating the group rather than executing them out of hand.

The layout wasn’t the hard part, but Jedao reflected on the mysteries of the Gwa Reality’s penal code. For example, prostitution was a major offense. They didn’t even fine the offenders, but sent them to remedial counseling, which surely cost the state money. In the heptarchate, they did the sensible thing by enforcing licenses for health and safety reasons and taxing the whole enterprise. On the other hand, the Gwa-an had a refreshingly casual attitude toward heresy. They believed that public debate about Poetics (their version of Doctrine) strengthened the polity. If you put forth that idea anywhere in the heptarchate, you could expect to get arrested.

So it was that Jedao headed for the cellblocks where one might find unlucky prostitutes and not the ones where overly enthusiastic heretics might be locked up overnight to cool off. He kept attracting horrified looks and wondered if he’d done something offensive with his hair. Was it wrong to part it on the left, and if so, why hadn’t Haval warned him? How many ways could you get hair wrong anyway?

The Gwa-an also had peculiarly humanitarian ideas about the surroundings that offenders should be kept in. Level 37, where he expected to find Meng, abounded with fountains. Not cursory fountains, but glorious cascading arches of silvery water interspersed with elongated humanoid statues in various uncomfortable-looking poses. Teshet had mentioned that this had to do with Gwa-an notions of ritual purity.

While “security” was one of the words that Jedao had memorized, he did not read Tlen Gwa especially quickly, which made figuring out the signs a chore. At least the Gwa-an believed in signs, a boon to foreign infiltrators everywhere. Fortunately, the Gwa-an hadn’t made a secret of the Security office’s location, even if getting to it was complicated by the fact that the fountains had been rearranged since the last available intel and he preferred not to show up soaking wet. The fountains themselves formed a labyrinth and, upon inspection, it appeared that different portions could be turned on or off to change the labyrinth’s twisty little passages.

Unfortunately, the water’s splashing also made it difficult to hear people coming, and he had decided that creeping about would not only slow him down, but make him look more conspicuous, especially with the issue of his hair (or whatever it was that made people stare at him with such affront). He rounded a corner and almost crashed into a sentinel, recognizable by Security’s spear-and-shield badge.

In retrospect, a simple collision might have worked out better. Instead, Jedao dropped immediately into a fighting stance, and the sentinel’s eyes narrowed. Dammit, Jedao thought, exasperated with himself. This is why my handlers preferred me doing the sniper bits rather than the infiltration bits. Since he’d blown the opportunity to bluff his way past the sentinel, he swept the man’s feet from under him and knocked him out. After the man was unconscious, Jedao stashed him behind one of the statues, taking care so the spray from the fountains wouldn’t interfere too much with his breathing. He had the distinct impression that “dead body” was much worse from a ritual purity standpoint than “merely unconscious,” if he had to negotiate with someone later.

He ran into no other sentinels on the way to the office, but as it so happened, a sentinel was leaving just as he got there. Jedao put on an expression he had learned from the scariest battlefield medic of his acquaintance back when he’d been a lowly infantry captain and marched straight up to Security. He didn’t need to be convincing for long, he just needed a moment’s hesitation.

By the time the sentinel figured out that the “medic” was anything but, Jedao had taken her gun and broken both her arms. “I want to talk to your leader,” he said, another of those useful canned phrases.

The sentinel left off swearing (he was sure it was swearing) and repeated the word for “leader” in an incredulous voice.

Whoops. Was he missing some connotational nuance? He tried the word for “superior officer,” to which the response was even more incredulous. Hey Mom, Jedao thought, you know how you always said I should join the diplomatic corps on account of my always talking my way out of trouble as a kid? Were you ever wrong. I am the worst diplomat ever. Admittedly, maybe starting off by breaking the woman’s arms was where he’d gone wrong, but the sentinel didn’t sound upset about that. The Gwa-an were very confusing people.

After a crescendo of agitation (hers) and desperate rummaging about for people nouns (his), it emerged that the term he wanted was the one for “head priest.” Which was something the language lessons ought to have noted. He planned on dropping in on whoever had written the course and having a spirited talk with them.

Just as well that the word for “why” was more straightforward. The sentinel wanted to know why he wanted to talk to the head priest. He wanted to know why someone who’d had both her arms broken was more concerned with propriety (his best guess) than alerting the rest of the station that they had an intruder. He had other matters to attend to, though. Too bad he couldn’t recruit her for her sangfroid, but that was outside his purview.

What convinced the sentinel to comply, in the end, was not the threat of more violence, which he imagined would have been futile. Instead, he mentioned that he’d left one of her comrades unconscious amid the fountains and the man would need medical care. He liked the woman’s concern for her fellow sentinel.

Jedao and the sentinel walked together to the head priest’s office. The head priest came out. She had an extremely elaborate coiffure, held in place by multiple hairpins featuring elongated figures like the statues. She froze when Jedao pointed the gun at her, then said several phrases in what sounded like different languages.

“Mongrel language,” Jedao said in Tlen Gwa, remembering what Haval had told him.

“What do you want?” the high priest said in awkward but comprehensible high language.

Jedao explained that he was here for Ahun Gerav, in case the priest only knew Meng by their cover name. “Release them and their crew, and this can end with minimal bloodshed.”

The priest wheezed. Jedao wondered if she was allergic to assassins. He’d never heard of such a thing, but he wasn’t under any illusions that he knew everything about Gwa-an immune systems. Then he realized she was laughing.

“Feel free to share,” Jedao said, very pleasantly. The sentinel was sweating.

The priest stopped laughing. “You’re too late,” she said. “You’re too late by thirteen years.”

Jedao did the math: eight years since he and Meng had graduated from Shuos Academy. Of course, the two of them had attended for the usual five years. “They’ve been a double agent since they were a cadet?”

The priest’s smile was just this side of smug.

Jedao knocked the sentinel unconscious and let her spill to the floor. The priest’s smile didn’t falter, which made him think less of her. Didn’t she care about her subordinate? If nothing else, he’d had a few concussions in his time (real ones), and they were no joke.

“The crew,” Jedao said.

“Gerav attempted to persuade them to turn coat as well,” the priest said. “When they were less than amenable, well—” She shrugged. “We had no further use for them.”

“I will not forgive this,” Jedao said. “Take me to Gerav.”

She shrugged. “Unfortunate for them,” she said. “But to be frank, I don’t value their life over my own.”

“How very pragmatic of you,” Jedao said.

She shut up and led the way.

Du Station had provided Meng with a luxurious suite by heptarchate standards. The head priest bowed with an ironic smile as she opened the door for Jedao. He shoved her in and scanned the room.

The first thing he noticed was the overwhelming smell of—what was that smell? Jedao had thought he had reasonably cosmopolitan tastes, but the platters with their stacks of thin-sliced meat drowned in rich gravies and sauces almost made him gag. Who needed that much meat in their diet? The suite’s occupant seemed to agree, judging by how little the meat had been touched. And why wasn’t the meat cut into decently small pieces so as to make for easy eating? The bowls of succulent fruit were either for show or the suite’s occupant disliked fruit, too. The flatbreads, on the other hand, had been torn into. One, not entirely eaten, rested on a meat platter and was dissolving into the gravy. Several different-sized bottles were partly empty, and once he adjusted to all the meat, he could also detect the sweet reek of wine.

Most fascinatingly, instead of chopsticks and spoons, the various plates and platters sported two-tined forks (Haval had explained to him about forks) and knives. Maybe this was how they trained assassins. Jedao liked knives, although not as much as he liked guns. He wondered if he could persuade the Kel to import the custom. It would make for some lively high tables.

Meng glided out, resplendent in brocade Gwa-an robes, then gaped. Jedao wasn’t making any attempt to hide his gun.

“Foxfucking hounds,” Meng slurred as they sat down heavily, “you. Is that really you, Jedao?”

“You know each other?” the priest said.

Jedao ignored her question, although he kept her in his peripheral vision in case he needed to kill her or knock her out. “You graduated from Shuos Academy with high marks,” Jedao said. “You even married rich the way you always talked about. Four beautiful kids. Why, Meng? Was it nothing more than a story?”

Meng reached for a fork. Jedao’s trigger finger shifted. Meng withdrew their hand.

“The Gwa-an paid stupendously well,” Meng said quietly. “It mattered a lot more, once. Of course, hiding the money was getting harder and harder. What good is money if you can’t spend it? And the Shuos were about to catch on anyway. So I had to run.”

“And your crew?”

Meng’s mouth twisted, but they met Jedao’s eyes steadfastly. “I didn’t want things to end the way they did.”

“Cold comfort to their families.”

“It’s done now,” Meng said, resigned. They looked at the largest platter of meat with sudden loathing. Jedao tensed, wondering if it was going to be flung at him, but all Meng did was shove it away from them. Some gravy slopped over the side.

Jedao smiled sardonically. “If you come home, you might at least get a decent bowl of rice instead of this weird bread stuff.”

“Jedao, if I come home they’ll torture me for high treason, unless our heptarch’s policies have changed drastically. You can’t stop me from killing myself.”

“Rather than going home?” Jedao shrugged. Meng probably did have a suicide fail-safe, although if they were serious they’d have used it already. He couldn’t imagine the Gwa-an would have neglected to provide them with one if the Shuos hadn’t.

Still, he wasn’t done. “If you do something so crass, I’m going to visit each one of your children personally. I’m going to take them out to a nice dinner with actual food that you eat with actual chopsticks and spoons. And I’m going to explain to them in exquisite detail how their Shuos parent is a traitor.”

Meng bit their lip.

More softly, Jedao said, “When did the happy family stop being a cover story and start being real?”

“I don’t know,” Meng said, wretched. “I can’t—do you know how my spouses would look at me if they found out that I’d been lying to them all this time? I wasn’t even particularly interested in other people’s kids when this all began. But watching them grow up—” They fell silent.

“I have to bring you back,” Jedao said. He remembered the staticky voice of the unnamed woman playing in Essier’s office, Meng’s crew, who’d tried and failed to get a warning out. She and her comrades deserved justice. But he also remembered all the gifts he’d sent to Meng’s children over the years, the occasional awkwardly written thank-you note. It wasn’t as if any good would be achieved by telling them the awful truth. “But I can pull a few strings. Make sure your family never finds out.”

Meng hesitated for a long moment. Then they nodded. “It’s fair. Better than fair.”

To the priest, Jedao said, “You’d better take us to the Moonsweet Blossom, assuming you haven’t disassembled it already.”

The priest’s mouth twisted. “You’re in luck,” she said.

Du Station had ensconced the Moonsweet Blossom in a bay on Level 62. The Gwa-an passed gawped at them. The priest sailed past without giving any explanations. Jedao wondered whether the issue was his hair or some other inexplicable Gwa-an cultural foible.

“I hope you can pilot while drunk,” Jedao said to Meng.

Meng drew themselves up to their full height. “I didn’t drink that much.”

Jedao had his doubts, but he would take his chances. “Get in.”

The priest’s sudden tension alerted him that she was about to try something. Jedao shoved Meng toward the trademoth, then grabbed the priest in an arm. What was the point of putting a priest in charge of security if the priest couldn’t fight?

Jedao said to her, “You’re going to instruct your underlings to get the hell out of our way and open the airlock so we can leave.”

“And why would I do that?” the priest said.

He reached up and snatched out half her hairpins. Too bad he didn’t have a third hand; his grip on the gun was precarious enough as it was. She growled, which he interpreted as Fuck you and all your little foxes. “I could get creative,” Jedao said.

“I was warned that the heptarchate was full of barbarians,” the priest said.

At least the incomprehensible Gwa-an fixation on hairstyles meant that he didn’t have to resort to more disagreeable threats, like shooting her subordinates in front of her. Given her reaction when he had knocked out the sentinel, he wasn’t convinced that would faze her anyway. He adjusted his grip on her and forced her to the floor.

“Give the order,” he said. “If you don’t play any tricks, you’ll even get the hairpins back without my shoving them through your eardrums.” They were very nice hairpins, despite the creepiness of the elongated humanoid figures, and he bet they were real gold.

Since he had her facing the floor, the priest couldn’t glare at him. The frustration in her voice was unmistakable, however. “As you require.” She started speaking in Tlen Gwa.

The workers in the area hurried to comply. Jedao had familiarized himself with the control systems of the airlock and was satisfied they weren’t doing anything underhanded. “Thank you,” he said, to which the priest hissed something venomous. He flung the hairpins away and let her go. She cried out at the sound of their clattering and scrambled after them with a devotion he reserved for weapons. Perhaps, to a Gwa-an priest, they were equivalent.

One of the workers, braver or more foolish than the others, reached for her own gun. Jedao shot her in the hand on the way up the hatch to the Moonsweet Blossom. It bought him enough time to get the rest of the way up the ramp and slam the hatch shut after him. Surely Meng couldn’t accuse him of showing off if they hadn’t seen the feat of marksmanship; and he hoped the worker would appreciate that he could just as easily have put a hole in her head.

The telltale rumble of the Blossom’s maneuver drive assured him that Meng, at least, was following directions. This boded well for Meng’s health. Jedao hurried forward, wondering how many more rounds the Gwa-an handgun contained, and started webbing himself into the gunner’s seat.

“You wouldn’t consider putting that thing away, would you?” Meng said. “It’s hard for me to think when I’m ready to piss myself.”

“If you think I’m the scariest person in your future, Meng, you haven’t been paying attention.”

“One, I don’t think you know yourself very well, and two, I liked you much better when we were on the same side.”

“I’m going to let you meditate on that second bit some other time. In the meantime, let’s get out of here.”

Meng swallowed. “They’ll shoot us down the moment we get clear of the doors, you know.”

“Just go, Meng. I’ve got friends. Or did you think I teleported onto this station?”

“At this point I wouldn’t put anything past you. Okay, you’re webbed in, I’m webbed in, here goes nothing.”

The maneuver drive grumbled as the Moonsweet Blossom blasted its way out of the bay. No one attempted to close the first set of doors on them. Jedao wondered if the priest was still scrabbling after her hairpins, or if it had to do with the more pragmatic desire to avoid costly repairs to the station.

The Moonsweet Blossom had few armaments, mostly intended for dealing with high-velocity debris, which was more of a danger than pirates if one kept to the better-policed trade routes. They wouldn’t do any good against Du Station’s defenses. As signals, on the other hand—

Using the lasers, Jedao flashed HERE WE COME in the merchanter signal code. With any luck, Haval was paying attention.

At this point, several things happened.

Haval kicked Teshet in the shin to get him to stop watching a mildly pornographic and not-very-well-acted drama about a famous courtesan from 192 years ago. (“It’s historical so it’s educational!” he protested. “One, we’ve got our signal, and two, I wish you would take care of your urgent needs in your own quarters,” Haval said.)

Carp 1 through Carp 4 and 7 through 10 launched all their shuttles. Said shuttles were, as Jedao had instructed, full of variable-coefficient lubricant programmed to its liquid form. The shuttles flew toward Du Station, then opened their holds and burned their retro thrusters for all they were worth. The lubricant, carried forward by momentum, continued toward Du Station’s turret levels.

Du Station recognized an attack when it saw one. However, its defenses consisted of a combination of high-powered lasers, which could only vaporize small portions of the lubricant and were useless for altering the momentum of quantities of the stuff, and railguns, whose projectiles punched through the mass without much effect. Once the lubricant had clogged up the defensive emplacements, Carp 1 transmitted an encrypted radio signal with the command that caused the lubricant to harden in place.

The Moonsweet Blossom linked up with Haval’s merchant troop. At this point, the Blossom only contained two people, trivial compared to the amount of mass it had been designed to haul. The merchant troop, of course, had just divested itself of its cargo. The nine heptarchate vessels proceeded to hightail it out of there at highly non-freighter accelerations.

Jedao and Meng swept the Moonsweet Blossom for bugs and other unwelcome devices, an exhausting but necessary task. Then, at what Jedao judged to be a safe distance from Du Station, he ordered Meng to slave it to Carp 1.

The Carp 1 and Moonsweet Blossom matched velocities, and Jedao and Meng made the crossing to the former. There was a bad moment when Jedao thought Meng was going to unhook their tether and drift off into the smothering dark rather than face their fate. But whatever temptations were running through their head, Meng resisted them.

Haval and Teshet greeted them on the Carp 1. After Jedao and Meng had shed the suits and checked them for needed repairs, Haval ushered them all into the business office. “I didn’t expect you to spring the trademoth as well as our Shuos friend,” Haval said.

Meng wouldn’t meet her eyes.

“What about the rest of the crew?” Teshet said.

“They didn’t make it,” Jedao said, and sneezed. He explained about Meng’s extracurricular activities over the past thirteen years. Then he sneezed again.

Haval grumbled under her breath. “Whatever the hell you did on Du, Sren, did it involve duels?”

“‘Sren’?” Meng said.

“You don’t think I came into the Gwa Reality under my own”—sneeze—“name, did you?” Jedao said. “Anyway, there might have been an incident . . .”

Meng groaned. “Just how good is your Tlen Gwa?”