“My heart has joined the Thousand, for my friend stopped running today.”

–Richard Adams, Watership Down

It’s a funny world.

When you ask people who love our genre—who write it, who read it, whose art is inspired and enriched by it—what books helped to form them, you’ll hear the same titles over and over again, shuffled like a deck of cards. Tolkien. McCaffrey. Bradbury. Butler. Some writers might cite Lewis or Lovecraft or Shelley, while others go to King and Friesner and Tiptree. But one strange constant—strange in the sense that it’s not really a genre novel at all, it’s not set in a fantasy world or filled with rockets shooting for the distant stars; the only monsters are all too realistic—is a quiet book about the inner lives of rabbits. Watership Down has, somehow, become a touchstone of modern genre, inspiring writers to write, readers to keep reading, artists to create, all in an attempt to touch once more the feeling we got from a book that owed as much to the British Civil Service as it did to the myths inside us all.

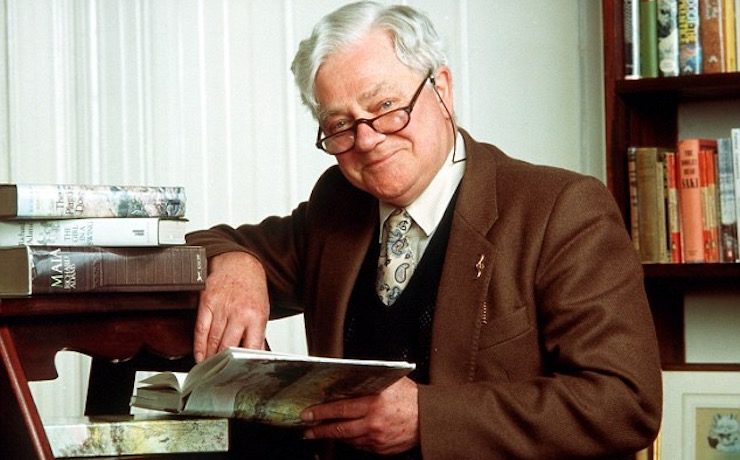

Richard Adams, author of Watership Down and many others, was born in 1920, and passed away on Christmas Eve of 2016. I like to think he knew how much he, and his work, meant to the creators of the world. Most of us did not know the man, but we knew the books he gave us: we knew how they changed us. We knew that we belonged to his Owsla, because he told us so.

Now we will tell you why.

Watership Down is the single book I have read, cover to cover, most often in my life. I think it’s 26 times; more likely, I should say it’s at least 26 times. The book is almost exactly the same age I am; it was published the year after I was born, but I think it’s safe to say that it was conceived a mite earlier.

I use passages from it to teach how to write true omniscient in my workshop classes.

But it’s more than that to me. It’s the book that I picked up at the age of six years old from beside the futon of a friend of my mother’s when I was bored out of my mind during an Visit to a house with No Kids Or Toys. I was already a rabid reader, but I had been mystified just the previous Christmas by a gift of the first Nancy Drew novel, The Secret in the Old Clock. That was too hard, and so was The Black Stallion Challenged, although I adored looking at the illustrations of horses.

But Watership Down… I didn’t understand one word in three, honestly. The primroses were over. What were primroses? What did it mean for them to be over? I had no idea.

I couldn’t stop reading.

That friend of my mother’s gave me that paperback copy of Watership Down, and probably made me a writer. Gentle reader, I memorized that book. It spoke to me on some soul-deep level that the children’s books I had been given did not and never had. Here were ambiguous heroes, suave villains, weaklings who were the only ones who knew the way to safety. Here was a place where it was okay to be smart; okay to be small; okay to be brave; not okay to be a bully.

Here was a story in which people could change. Where a neurotic weakling can become a clever leader, and a loving parent. Where a militaristic authoritarian could be tempered into a wise old warrior who spends life charily. Where a bully out for the main chance could, by simply being willing to learn and listen and think and interrogate his own cultural conditioning, become a legendary hero.

If one line in all of literature gives me a chill down my spine, it is this: “My Chief Rabbit told me to defend this run.” In some ways, my entire aesthetic as an artist and perhaps as a human being derives from that moment. The refusal to bow down to tyranny, to overwhelming force. The death-or-glory stand.

The hill that you will die on.

There are people who dismiss it as a children’s novel, and those people are fools. Because Watership Down is a war novel; it’s a social novel; it’s a Utopian novel; it’s a Bildungsroman; it’s a book about the character growth of an interlocking and interdependent group of strangers and uneasy allies who become, perforce, a family.

Watership Down didn’t make me who I am. But along with one other book, Peter Beagle’s The Last Unicorn, it showed me who I could become. If I had the courage to defend that run.

–Elizabeth Bear

(author, Karen Memory and others)

Watership Down was completely unlike anything else I’d read, when I was lent a copy at the age of—nine? Ten? With its scholarly chapter-headers and vivid and dense description of the countryside, and narrative that was by turns spiritual and brutal. Later I read The Plague Dogs and Shardik, but it was the Lapine world that had captured me from the start.

Perhaps children are all environmentalists, until they’re taught otherwise, and perhaps they’re similarly idealists. The destruction of Hazel’s home warren was dreadful to me, but more dreadful were the willful self-delusion of Strawberry’s warren and the deliberate cruelty of Efrafa.

The more I remember of the story, now, the more I can’t help but view it through the political lens I have acquired as an adult. For self-delusion read climate denial, and for deliberate cruelty, read benefit sanctions.

Hazel’s new warren on Watership Down, including rabbits from three very different warrens and from farm hutches besides, with a seagull ally and a willingness to build bridges with former enemies, feels like the diverse and forward-looking country I grew up in.

I do not live there anymore.

–Talis Kimberley

(songwriter, Queen of Spindles and others; Green Party politician)

I’m a lifelong and compulsive re-reader, but I have never re-read a book by Richard Adams. In each one I did read there was something that was just too hard to take. I’ve read overtly much more upsetting or heartbreaking or disturbing books, but there was just something about the way he wrote. I tried to re-read both The Girl in a Swing and The Plague Dogs because I wanted to see how he did a couple of things—the double set of explanations, mundane and supernatural, in the first; and the amazing eucatastrophe of the second. And I still mean to reread Watership Down, but when I begin, the stinging of the deepest bits even in memory is too much. I’d really like to have a more ordinary experience with his work as I do with that of other writers whom I admire, rereading until I know entire passages; but at least I can say that I do not forget it, ever.

–Pamela Dean

(author, Tam Lin and others)

When I was a young boy, my uncle Tommy—the closest thing I had to a big brother—handed me a book and told me, “This is the most moving story about rabbits you’ll ever read.”

“I… haven’t read any moving stories about rabbits.”

“I know.”

Tommy had a very wry sense of humor.

But as I read Watership Down, what always got to me was the scene in Cowslip’s warren where the tamed rabbits are making mosaic art, and all our rabbit heroes see is a bunch of pebbles. In that moment, I felt that scything divide between “What I understood” and “What these characters understood” in a way that none of my English classes on “point of view” had never been able to convey. The things I loved about Fiver and Bigwig and Hazel (and Rowf and Sniffer) were merely intersections, the places where their animal consciousness overlapped with my humanity. Yet I loved them all the more for that.

Since then, I’ve written about the mad scientist’s killer squid, and bureaucracy-obsessed mages, and sentient viruses. And every time I write a new character, I wonder: what’s the mosaic for this person? What’s the thing everyone else can see that this character can’t?

Years later, I gave my eldest daughter a copy of Watership Down. I told her it was the most moving story about rabbits she’d ever read. She told me she’d never read any moving stories about rabbits.

I told her I knew.

–Ferrett Steinmetz

(author, Flex and others)

I’ve got a paperback Avon Books edition of Watership Down that my mom picked up for me when I was a kid. I can’t read this copy anymore—the spine’s all but dust—so I can’t quote the one passage I’m thinking of, but that’s okay since it still lives and breathes in the space behind my eyeballs. In it, Fiver, Hazel, and the others have learned about the destruction of their old warren. Adams treated the background narration of the novel as if he were doing the voiceover on a wildlife documentary, and he wrote that the rabbits collapsed under the pain of the news. Rabbits don’t (Adams claimed) have that peculiar human trait in which they can remove themselves from tragedy. When rabbits hear that one of their own kind has suffered, they internalize that suffering and experience it themselves.

This is a hell of a thing for an eleven-year-old kid to read. Especially as I grew up in a household where the evening news was a ritual, and I was the kind of kid who read books while the news was on. I first read that passage about the tragedy at the warren during a piece about the murders of protesters in Burma. And then, just like the worst and strongest kind of magic, the stories on the news changed for me forever. I cried a lot, that night.

–K.B. Spangler

(author, Digital Divide and others)

I fell in love with Watership Down because of Fiver, Richard Adams’s Cassandra, who saw too much, and because of how his brother Hazel loved him. To some extent, all the characters in Watership Down felt like me. They were all wild and reactive. I was one of those girls with undiagnosed ADHD, and I have some similarities to wild animals. ADHD isn’t just disorganization, as it happens; it often comes with a suite of other quirks. Mine, in particular, are a lack of sensory filters. Loud or sudden sounds, bright lights, or any strong sensation would send me into an emotional tailspin that I wasn’t even aware of. I just felt stressed and miserable all the time. People constantly told me to get over it or to stop being so sensitive.

Fiver was like me. Fiver felt the awful currents of everything around him. I read and reread, greedily, the scene where Fiver was accused of just wanting more attention for himself. I loved Hazel for sticking up for his brother against everyone else’s dismissal and for trusting him when no one else did. When Hazel, tired and stressed, stopped listening to him in the Warren of Snares, my heart just about broke. But, proven wrong Hazel apologized, and after that, everyone listened to Fiver. He even got his own happy ending.

I’m now writing my own novel about wolves and coyotes in the naturalistic style of Richard Adams, and I hope the feeling of friendship, understanding, and belonging come through in my world as they did in Adams’s.

–Alex Haist

(author)

There are certain books you are, if you are lucky, run across before you understand what an author is. Possibly, slightly before you understand what fiction really is. These are the books that are more true to you than reality. Two of those books have embedded their messages in my being. One was The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. It led me to a fine appreciation of the absurdity of reality. The other was Watership Down. It taught me a lot more. About being weak, and being strong, and being tough, and how the three all have their own power. It taught me about how the world can be senseless and cruel, and how we have to fight for our meaning in it.

More than anything, it taught me to look below the surface. It was accurate, as much as a book like that can be. I learned about rabbit warrens and how they run, and I never found a wrongness. It showed me perspective—how my grandpa’s sportscar could be a monster. And it taught me that even the weakest and most adorable animal is still something to respect.

The lessons in that book hold true to my life today. I am currently holding together a voluntary association of 60+ people, who work without pay, who are united in a goal we have decided for ourselves. It’s part bloody mindedness, and part looking for our own home. There have been traps, and lessons, and joy and costs along the way, and there has been failure. And that failure is part of what happens, and from the seeds of that failure grows success.

And that’s some of what Watership Down means to me. It’s not about the destination, but the journey. Not about what I can get, but about the things I can do along the way. Companions are the people who find you in life. Cherish them. And when needed… fight.

–Chris “Warcabbit” Hare

(game developer, project lead City of Titans)

Richard Adams’ Watership Down was one of the first books that I remember reading as a child that was both realistic and fantastic. This worked because Adams created an entirely credible world of rabbits, a world in which they had their own language, their own mythology, their own history. Then he sprinkled in the fantastic in the form of Fiver’s visions. These visions are oracular and true, and their magical nature becomes authentic because of the matter-of-fact way that Adams presents them in the story. Of course Fiver has visions, and of course his brother Hazel believes them. Hazel believes them and so we believe them, too.

This magic of Fiver’s—as well as the magic wrought by the numerous myths of El-ahrairah—is contrasted with the deep brutality that the rabbits face in trying to establish their own warren. The violence is often sudden and unflinching. When one of the rabbits, Bigwig, is caught in a snare Adams writes the scene with the same matter-of-factness as Fiver’s visions. He does not glamorize the violence but neither does he shy away from the reality of an animal caught in a wire.

Richard Adams taught me that establishing a credible world is not just down to the details but also a matter of belief. The author believes, and that’s apparent in his tone. The rabbits and their struggles and their stories are real to him. Because he believes, his characters believe, and so do we. The rabbits of Watership Down breathe and talk and tell their stories because we believe in them.

–Christina Henry

(author, Lost Boy)

The first time I heard of Watership Down was an aunt saying how much she’d enjoyed it. When I heard it was about rabbits, I was intrigued. I wanted to read it, but evidently, it wasn’t meant for young kids, which seemed strange, given the subject matter. A few years later, I was in the hospital for surgery, and my aunt lent me her copy. I devoured it. I finished, and then I started again.

Watership Down was a revelation to me. It took what I considered very ordinary and rather dull creatures, and it created a fascinating and intricate world around them. It was fantasy, yet it was grounded in reality, something I hadn’t seen before that. And while it did work for me as an older child, I would return to it as I got older and discover new depths. Every new read revealed a fresh layer, as my own experience of the world broadened.

Of course, I did go on to read and enjoy other Adams works—The Plague Dogs, Shardik, Maia—but it is Watership Down that had the most influence on me as a writer. It showed me how deep even a narrow sliver of the world can be. When asked to name my favorite books, my answer may vary, depending on the audience, but more often than not, it’s Watership Down.

–Kelley Armstrong

(author, City of the Lost and others)

My introduction to Adams’s work was in a video store when I was eleven. I rented what looked like a fun little movie about some rabbits, and upon watching it alone in my room one night, was instantly smitten. There was an unexpected richness to the world these rabbits inhabited, with a creation myth and their own words for human things, and even different forms of government between different warrens. It was such an inviting piece of art.

When I finally came across the novel in a bookstore, I fell even more in love. There were plenty of animal fantasy stories in which animals put on little waistcoats and had little houses and clutched miniature teacups made out of acorn caps, and those are all well and good, but didn’t hold the same allure as a book that would occasionally teach me incredible animal facts such as “does will sometimes re-absorb their young if the warren is too crowded.” I loved seeing the world through the eyes of what I could imagine were real rabbits, and finding a depth there without needing to fall back on classic humanizing characteristics. He may have taken liberties, including giving a rabbit supernatural powers, but he also limited them in ways I appreciated, like their strange encounters with the too-human rabbits of Cowslip’s warren. They were still being written as animals, not as humans who just happen to be animals.

There is a lot to love about Watership Down, but that was probably what I loved most. It is easy to write inhuman creatures as exactly analogous to humanity, but it’s more fun and often interesting to look at the world we live in from an inhuman perspective. And though in my case it’s a little different, I feel as if this has carried over into my own work in the way I write monster characters. They are not human, and don’t have the same needs as humans, nor are they mindless killing machines. They’re just strange creatures trying to get by. Though they do a little more killin than the Watership rabbits ever did.

–Abby Howard

(artist)

It began in an elementary school library. We were K through Six, which meant we had students ranging from six years old all the way up to thirteen, and meant that our library was carefully curated and segmented to make it safe and accessible to all students. As a second grader, I was limited to the front of the library, and to checking out two books a week, which led—naturally—to me gravitating toward the thickest books I could find. I was starving among plenty.

And then there was a filing error. Watership Down, in its three hundred plus page glory, was shoved in among the Paddington books as suitable for young readers. I grabbed it and ran. At that age, I was content to read anything—legal briefings, dictionaries, encyclopedias, appliance manuals—as long as it was, well, long.

I reached the end of the book. I turned it over. I started it again. I read it three times before I had to return it to the library, and the only reason I didn’t check it back out immediately was that our school librarian wouldn’t let me (and was, in fact, appalled that her assistant had let me have it in the first place).

Watership Down was the first book I’d read that showed me what it could be like to create a world where animals weren’t little humans in fur, but where they weren’t animals, either. It taught me about myth and the power of words, about the ways a story could change everything. It taught me about death in ways that people still believed I was too young and too fragile to understand. It talked to me, not over me or down to me, and when I didn’t understand, the tone made it very clear that it wasn’t my fault: there was even a glossary at the back, because everyone, however old or wise, was going to have trouble understanding certain parts of the story.

This wasn’t the book that made me want to be a writer. But it was the book that made me feel like it was possible. It was the book that gave me words to fit the size and scope of my grief, on the occasions when grief was unavoidable, and I would not be who I am today if I had not made it a part of my foundation when I was someone else, a very long time ago.

–Seanan McGuire

(author, Down Among the Sticks and Bones and others)