John Persons is a private investigator with a distasteful job from an unlikely client. He’s been hired by a ten-year-old to kill the kid’s stepdad, McKinsey. The man in question is abusive, abrasive, and abominable. He’s also a monster, which makes Persons the perfect thing to hunt him. Over the course of his ancient, arcane existence, he’s hunted gods and demons, and broken them in his teeth.

As Persons investigates the horrible McKinsey, he realizes that he carries something far darker than the expected social evils. He’s infected with an alien presence, and he’s spreading that monstrosity far and wide. Luckily Persons is no stranger to the occult, being an ancient and magical intelligence himself. The question is whether the private dick can take down the abusive stepdad without releasing the holds on his own horrifying potential.

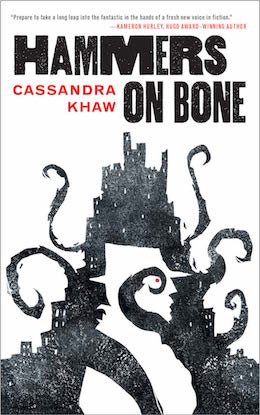

Cassandra Khaw’s dark fantasy noir Hammers on Bone is available October 11th from Tor.com Publishing.

Chapter 1

Murder, My Sweet

“I want you to kill my step-dad.”

I kick my feet off my desk and lean forward, rucking my brow. “Say that again, kid?”

Usually, it’s dames trussed up in whalebone and lace that come slinking through my door. Or, as is more often the case these days, femme fatales in Jimmy Choos and Armani knock-offs. The pipsqueak in my office is new, and I’m not sure I like his brand of new. He’s young, maybe a rawboned eleven, but he has the stare of someone three times his age and something twice as dangerous.

Not here to sell cookies, that much is obvious. I saw him take a firm, hard look at the door, take in the sign I’d chiseled on the frosted glass: John Persons, P.I.

“I said—” He plants his piggy bank on my desk like a statement of intent. “—I want you to kill my step-dad.”

“And why’s that?”

“Because he’s a monster.”

You learn things in this line of work. Like how to read heartbeats. Any gumshoe can tell when a darb’s lying but it takes a special class of sharper to differentiate between two truths. Whatever the reality is, this kid believes the spiel he’s selling, marrow and soul. In his eyes, his secondary sad sack of an old man’s a right monster.

I let a smile pull at my mouth. “Kid. I don’t know what you’ve been hearing. But I’m a PI. You want a life taker, you gotta go somewhere else.”

Right on cue, a whisper crackles in the back of my skull, like a radio transmission from the dead, shaky and persistent: wait wait wait.

The kid doesn’t even flinch. “You kill when you have to.”

I knot my arms over my chest. “When I have to. Not when a gink with a bag full of change tells me to. Big difference.”

A muscle in his cheek jumps. Brat doesn’t like it when someone tells him no. But to his credit, he doesn’t break form. He sucks in a breath, nice and slow, before exhaling. Class act, this one. If I ever meet his folks, I’m going to have to tip a trilby to them.

“Well,” He announces, cold as a crack-haired shyster on the court room floor. There are plenty of problems with the body I’m wearing, but we tend to see eye-to-eye on this brand of vernacular. “You have to.”

“And why’s that?”

“Because if you don’t, my brother and I are going to die.”

Please.

I sigh, feel the air worm out of my lungs. I could do with a cigarette right now, but it’d be impolite, not to mention stupid, to leave a client hanging about this dive. No telling if he’s going to stay put, or if he’s going to paw through places he don’t belong. And I couldn’t afford that.

So, I shake out a few folders instead, rearrange a stack of papers. Just to give my hands something to do. “Tell your mom to call child services. The bulls will have your old man dancing on air in no time.”

“I can’t.” He shakes his head, curt-like. “He did something to my mommy. And he’ll do something to the police too. I know it. Please. You’re the only one who can help.”

“What makes you say that?”

“Because you’re a monster too.”

Well. This got interesting. I crook a finger at him, beckon the midget closer. He doesn’t hesitate, scoots right up to the edge of the desk and tilts his head forward like I’m some favorite uncle about to ruffle his hair. I take a whiff. Drink his scent like a mouthful of red.

—black and animal bile, copper and cold spring water, herbs and life of every dimension, almost enough to hide the stink of cut-open entrails, of muscles split and tethered to unimaginable dreams, a composition of offal and spoor and predator breath—

“This is some bad shit you’ve gotten mixed up with there.”

“I know.” He fixes his eyes to mine. You could carve Harlem sunsets with that look he’s wearing. “Will you take the job?”

Wehavetowehavetowehaveto.

Persistent as bear traps, those two. I smile through my teeth and the pleas that won’t stop pounding in my head. “Kid, I don’t think I have a choice.”

* * *

Croydon’s a funny place these days. I remember when it was harder, when it was chisellers and punks, knife-toting teenagers and families too poor to make it anywhere else in grand old London, when this body was just acres of hurt and heroin, waiting to stop breathing. Now Croydon’s split down the middle, middle-class living digging its tentacles into the veins of the borough, spawning suits and skyscrapers and fast food joints every which way. In a few years, it’ll just be another haunt for the butter and egg men. No room for the damned.

Home, sighs my ghost.

“No,” I correct him, adjusting the folds of my collar with a careful little motion. “Not anymore.”

I roll my shoulders, stretch to my full height, cartilage popping like a tommy gun. The cold feels good, real good, a switchblade chill cutting deep into the cancer of a thousand years’ nap. Shading my eyes with a hand, I check the address the kid had chicken-scrawled on a receipt. Close enough to walk, and about a block down from this old Caribbean place I remember from the ‘90s.

I light my first cigarette of the decade. Inhale. Exhale. Let my lungs pickle in tar and tobacco before starting down the worn-down road. It doesn’t take long before I get to my destination. The house is a dump. Crushed between council estates, it sits in a row of identical structures, a thin slant of property like a hop head drooping between highs.

“Anyone home?” I bang on the door.

The wood creaks open, revealing a scared-looking bird and the reek of stale booze. “Who are you?”

“School authorities.”

She stiffens. “What do you want?”

Smoke leaks from between my teeth as I flash a grin, all shark. “I’m here about your son’s attendance records. The school board’s not happy.”

“I’m sorry—”

I don’t let her finish. Instead, I wedge a foot through the gap and shoulder the door open, knocking the latch free. The broad scuttles back, alarmed. I can see the cogs in her head wheeling as I swagger in: what’s this shamus doing dripping rain in her foyer? As she slots together an objection, I slice in between.

“So, what’s the deal here, sister? You making the runt work sweatshops or something?”

“Excuse me?” She’s staring. They always do. These days, it’s all bae and fleek, bootylicious selfies and cultural appropriation done on brand. That puts me in a weird linguistic space, with my chosen vocabulary. I mean, I could embrace the present, but I feel a responsibility to my meat’s absentee landlord.

“Your son.”

Her eyes glitter, dart away like pale blue fish.

“Well?” I press, smelling advantage, blood in brine.

“I wouldn’t do something like that to my special boy.”

“Yeah?” I champ at my cigarette, bouncing it from one corner of my mouth to the other. There’s a pervasive smell in the hallway. Not quite a stench, but something unpleasant. Like the remnants of a molly party, or old sex left to crust on skin. “What about his old man? He working the kid? That why your son isn’t showing up at school?”

The broad twitches, shoulders scissoring back, spine contracting. It’s a tiny motion, one of those blink-and-you-lose-it tells but oh, do I catch it. “My fiance doesn’t involve our sons in hard labor.”

“Uh huh.” I rap ash from my cigarette and grin like the devil come to dine on Georgia. “Mind if I look around?”

“I really don’t think—“

You gotta love the redcoats. Americans, they’re quick to tell you to make with the feet. But the Brits? It just ain’t in them to be rude. I take one last, long drag before I stub out my smoke in the aging carpet and start deeper into the house, the bird’s complaints trailing behind like a slither of organs.

The stink grows stronger: less human, more maritime malfeasance. A reek of salt and hard use, of drowned things rotten with new life. An old smell, a childhood smell. I walk my fingertips across the moldering wallpaper, black-blotched like some abused housewife. Under my touch, visions bloom.

Ah.

“Where’s the mister?”

“I’m sorry? I don’t see how any of this is—“

“—my business?” I interrupt, the house’s memories still greasing my palate. “You want to know how this is my business?”

“Yes, I—”

I spin on a heel and bear down on her, all six feet of me on five-feet-nothing of her. I breathe her scent in, eggy and slightly foul, a barely concealed aftertaste. “My business is determining if you’re solely responsible for the stories we’ve been hearing, or if your man is equally culpable. Now, you look like a smart broad. I’m sure you understand what I’m getting at here. If you want to take full responsibility for the shit that’s gone down, be my guest. But if you’d rather I give you a fair shake, you’ll tell me where your honey is so I can ask some questions.”

She flinches like I’d clip a dame of her size, mouth slumping under its own weight. “He’s out. He’s working at the brickworks.”

I glide my tongue along the back of my teeth, counting each stump before I start again. “Where?”

Silence. A lick of chapped, bloodless lips.

“Sister, here’s some free advice. Whatever mess you’re in, you should clean it up and get out.”

“Excuse me? I—“

I cock a bored stare. “You got a mug like a boxer. You want the same for your boys?”

Her fingers twitch to her face. I’m lying, of course. The thing wearing her sweetheart was careful. If there are teeth marks, they’re secreted beneath second-hand hems, pressed into spaces sacred to lovers. But guilt is a funny kind of magic.

I watch in silence as she gropes the cut of her jaw, the line of her nose, features spasming with every circuit, every new or imagined fault. By the time we make eye contact again, her gaze is frayed, wild with visions of things that don’t exist. I tilt my head.

“I think you should—” She declares at last.

I stab my tongue against the inside of a cheek and cluck in disapproval. “I shouldn’t do anything, sister. You, though, you need to give me the address of your man’s workplace.”

“Fine.”

The skirt punches a bony finger at the window, straight at the factory at the end of the road. It’s an ugly thing. Most places in London, the businesses will try to blend in with the neighborhood, mix a little effort into the mortar, so to speak. But this was the brickworks, the smoke-clogged uterus of the English capital. It was never meant to be beautiful. And frankly, it ain’t. The building in the distance, with its boneyard of chimneys, its cellblock windows, is like the corpse of a god that’s been left to rot, picked-over ribs swarming with overall-wearing insects. “That one there?”

She nods.

It catches her off-guard when I turn and show myself out. Almost, she calls out to me. I can hear it in the way her breath shortens and snags on the edge of a doubt, nervous, her voice a frayed little thread. But I don’t look back, don’t slow. Not even when I hear the shuffle of slippers on linoleum, a sound like wait and please come back. Just grab the door and yank it shut behind me, the rain painting my trenchcoat the classic, glimmering greys of London.

Excerpted from Hammers on Bone © Cassandra Khaw, 2016

The excerpt was originally published May 31, 2016