There’s one thing I’ve learned from researching our founding SFF authors: writers used to be a hell of a lot cooler. Not to insult any of our modern masters—far from it! They’re doing their best with the era they were dealt. But skim over the history of Harlan Ellison. Take a look at Robert Heinlein’s life, or Kurt Vonnegut’s, or Frank Herbert’s or Philip K. Dick’s. You’ll find stories of street brawls, epic rivalries, tumultuous love lives, hallucinations.

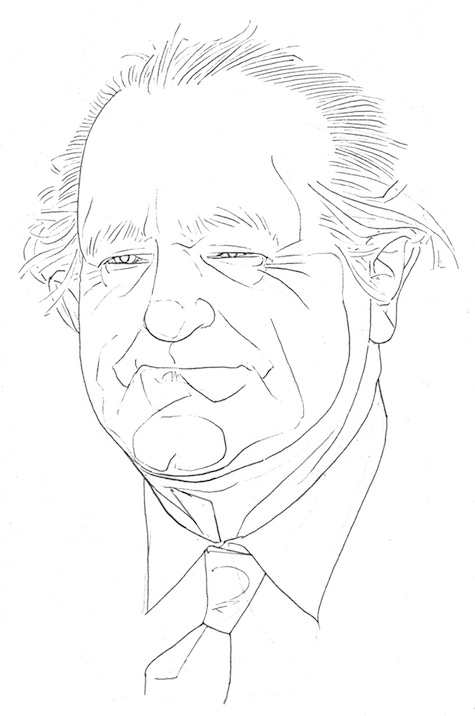

And then you get to Jack Vance, and the more you read the more you expect to learn that the man wrestled tigers for fun.

He was a self-taught writer, but in a way very different from Ray Bradbury. He was in and out of school as money allowed, sometimes taking classes at Berkeley but often having to support himself and his mother. Because of this, it was vitally important to him that his writing earn him a living.

When World War II started, Vance was told he was too nearsighted to enlist. He memorized an eye chart so he could make it into the Merchant Marine, and served throughout the War, writing short stories (using a clipboard as a portable desk) on the decks of his ships.

He became an engineer, and, like Heinlein, spent large amounts of time building things—in Vance’s case, he built his house, tearing sections down and then rebuilding to suit his family’s needs or his moods. He also built a houseboat, which he shared with Frank Herbert and Poul Anderson; the three writers used to sail around Sacramento Delta together.

He traveled constantly in his youth, and incorporated the travel and the writing into his home life in an extraordinary way, as his son, John related to the New York Times:

“They traveled often to exotic locales—Madeira, Tahiti, Cape Town, Kashmir—where they settled in cheap lodgings long enough for Vance to write another book. ‘We’d hole up for anywhere from a couple of weeks to a few months,’ John told me. ‘He had his clipboard; she [Vance’s wife, Norma] had the portable typewriter. He’d write in longhand, and she’d type it up. First draft, second draft, third draft.’”

He loved P.G. Wodehouse at least as much as Weird Tales.

An (extremely incomplete) list of his admirers includes: Neil Gaiman, George R.R. Martin, Dean Koontz, Michale Chabon, Ursula K. Le Guin, Tanith Lee, Paul Allen, and Gary Gygax, who based much of the magic system in Dungeons & Dragons on Vance’s work.

Here are some of the awards Jack Vance received: 3 Hugo Awards, for The Dragon Masters, The Last Castle, and his memoir This is Me, Jack Vance!; a Nebula Award for The Last Castle; a World Fantasy Award for Lyonesse: Madouc; a ‘Best First Mystery’ Edgar Award for The Man in the Cage; and a World Fantasy Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1984. The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America made him its 14th Grand Master in 1997, and he was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 2001

Jack Vance played many instruments, including ukulele, harmonica, washboard, kazoo, and cornet, and occasionally played with a jazz group in Berkeley.

He wrote three mystery novels under the “Ellery Queen” moniker: The Four Johns, A Room To Die In, and The Madman Theory

He created many sci-fi and fantasy landscapes, among them Dying Earth, Lyonesse, Demon Princes, Gaean Reach, and Durdane. The “Dying Earth” subgenre has proved so popular that it’s still in use today—George R.R. Martin recently edited Songs of the Dying Earth, an anthology which included stories by Neil Gaiman, Dan Simmons, Elizabeth Moon, Tanith Lee, Tad Williams, and Robert Silverberg.

Name of the fan-funded, 45-volume set of Vance’s complete works, in the author’s own preferred editions: Vance Integral Edition. Name of the fan-made database you can use to search VIE: Totality. Number of the times the word “mountebank” appears in his fiction: 17

Did we mention that he went blind in the 1980s, but kept writing anyway? His final work, the Hugo-winning memoir mentioned above, was published in 2009.

And of course the most important thing was that in the midst of all of these basic facts, when he wasn’t building houses or making music or packing his family up and moving to Marrakesh, he was writing extraordinary novels, wrestling with language and ideas until he created new worlds. And then he gave those worlds to us.

This post was originally published August 28, 2013.