Welcome to Freaky Friday, where we’re mining the deepest caverns of paperback horror fiction then dragging what we find to the surface, where it screams and cries tears of blood, begging to be returned to the darkness.

Before British Folk Horror blossomed up out of obscurity again with Michael Reeves’s 1968 Witchfinder General—starring Vincent Price as that deeply unpleasant detector and burner of witches, Matthew Hopkins—there was Satan’s Child. Written in 1968 by Peter Saxon, it kicks off with a suspected witch, Elspet Malcolm, being burned at the stake in a Scottish village sometime back in the early 18th century. Her two children are understandably alarmed and decide it’s unwise to stick around. After almost decapitating their stepfather with a pike, young Iain, her son, and Morag, her daughter, head for the hills. Morag gets sold into service but Iain heads for Tibet (maybe? could also be any vague Eastern locale with occult monks?) and learns to be an actual witch, which his mother wasn’t, then he comes back to the village of Kimskerchan and kills everyone who sent her to the stake. This is what’s known as irony.

Death Wish meets The Witchfinder General—this is cheapjack, lo-fi, grotty potboiler pulp entertainment from start to finish, but that doesn’t mean it’s not good. After all, the national food of Scotland is sheep guts stuffed inside stomach lining with a bunch of oatmeal, and yet that low class cuisine hasn’t stopped Scotland from producing Sean Connery.

Maybe the most macho fictitious person who never existed, Peter Saxon was a pen name used by authors W.Howard Baker, Rex Dolphin, and Wilfred McNeilly, among others, to turn out pulp novels, their efforts overseen by Baker who ensured that the their books about mad Africans (Black Honey, 1972), mad scientists (The Disorientated Man, 1967), and mad surgeons (Corruption, 1968) were full of descriptions of nubile girl-flesh, sadistic violence, and sexy swinging. Saxon was most famously the author of The Guardians series, five books about square-jawed, tweed-and-black briar pipe types investigating haunted houses, underwater vampires, voodoo cults, and Australians. They were the first modern day occult investigating team in the tradition of Carnacki the Ghost Finder and a forerunner of Scooby Doo. But 1967’s Satan’s Child came even before The Guardians existed and although it only runs a scant 189 pages it is one of the first heralds of the folk horror revival.

Folk horror is horror rooted in the landscape, unearthing evil from beneath the soil, dragging it to the surface still caked in dirt, the terror of the lonely wilderness, fear of the vitality of the forces that animate nature. Authors like Arthur Machen and Algernon Blackwood worked this land around the turn of the 20th century, but in the 1960s it bloomed forth from its slumber from the pens of authors like Susan Cooper and in films like The Witchfinder General, Blood on Satan’s Claw, and The Wicker Man. Peter Saxon’s Satan’s Child takes folk horror and cross-pollinates it with ’70s revenge narratives, turning it into a squalling mutant of its own making.

Written in a dank faux-Scots dialect (“She’s a tongue that would clip cloots. She’d gar ye puke.”) it’s set in the early 18th century when people in the remote and crappy village of Kimskerchan still remember the fear of witches fomented by King James VI in 1589 when he embarked on a brutal series of witch trials after suspecting that witches had sent a storm to drown his future wife. Falsely accused of being a witch, then tied to a cart and driven through town, Elspet Malcolm’s humiliation and burning takes time out to dwell on the way the blood “sprayed from her back and buttocks each time the lash fell” and when she burns the narrator pauses to describe the “flaming forest of her pubic hair” giving one of the jealous women who helped frame her an opportunity to make a quip about Elspeth’s “burning bush.”

After young Iain and Morag go on the run, however, the book settles down into a less titillating vein and becomes downright evocative, describing the way a rural community grows and struggles in the years that Iain is oversees learning magic with some kind of vaguely indicated Eastern cult of mystics (not Satanists, the book is clear, even though during his final initiation ceremony he wears the Dread Talisman of Set, which is the severed boner of an ancient Egyptian necromancer). Iain returns to Kimskerchan and the book moves briskly through his revenge murders almost like a stalk n’slash horror movie as he eliminates the men who killed his mother, one by one. It would be boring bloodshed if Iain didn’t cleverly turn each victim’s weaknesses against them. He gives one farmer who helped kill his mother a beautiful, enormous, Black Philip-y bull that he’s eager to breed, but the animal’s enormous penis kills every cow that comes within its reach until ultimately the bull gores his owner to death (its horns “garlanded with her husband’s guts”) and then has sex with the farmer’s wife, which doesn’t end well for her. What’s up with horror fiction and bull/human sex anyways?

Pricker Gill, the witchfinder who fabricated the evidence against Elspeth, has moved to France and become a gentleman of means, but Iain tricks him into accusing his own daughter of witchcraft and torturing her until her thumbs must be amputated. The priest who let his mother go to the stake becomes a gambling junkie and is thereby ruined in a dreamy, hallucinogenic sequence. The rich landlord who orchestrated it all is seduced by Iain himself who has transformed into Lady Mary Cameron of Glenlomond in order to enter into an affair with the man, then destroy him.

Things come to a climax as Iain’s revenge plan runs afoul of a local witch with a secret identity and it ends on a sort of an ersatz Herman Hesse note of spiritual kumbaya. One thing that may account for the high level of the writing and the way the story wastes no time screwing around is that the author behind the Peter Saxon name this time is Wilfred McNeilly, a Scotsman who wrote a comic strip for 15 years and referred to himself in his weekly poetry-reading spot on Ulster TV as the “Bard of Ardglass.” He passed away of a heart attack at age 62 and his granddaughter writes:

“He was a massively contradictory character, outrageous when drunk, and no stranger to magistrates courts in both Ulster and London in the aftermath of a wild binge, yet shy and courteous at all other times…He died as contented a man as any hedonistic novelist could. The contract had been signed days before and an advance been paid, out of which he had bought himself a new word processor and at least one bottle of the whisky that he was so fond of. His one regret would have been that the bottle was still half-full at the time of his attack.”

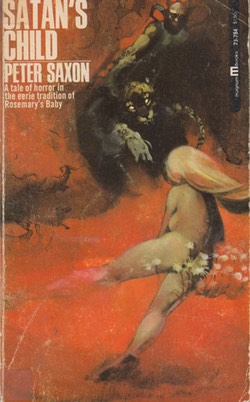

With gorgeous cover art by Jeffrey Catherine Jones, and a blurb that screams “A tale of horror in the eerie tradition of Rosemary’s Baby” in the obligatory manner of the day, Satan’s Child punches above its weight, a folk horror Death Wish for the Swinging Sixties. With additional bull sex. What more could any reader want?

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today; his previous novel was Horrorstör, about a haunted IKEA, and his latest novel, My Best Friend’s Exorcism, is basically Beaches meets The Exorcist.