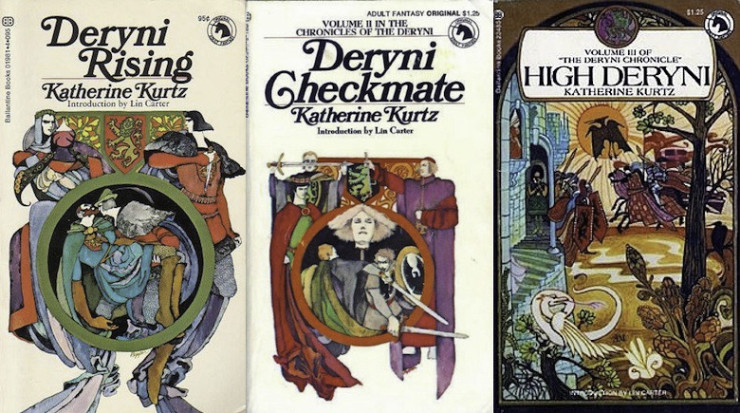

As I think about the reread of Katherine Kurtz’s first published trilogy before I move on to the second published series (which actually moves backward in time), what strikes me is that, for all their problems, their wobbles and plotholes, the first three books hold up amazingly well. I still love many of the things I loved then, and I see where my own writing picked up not only ideas and characters, but also Don’ts and No’s—things that made me say, even then, “Hell, no. It should be this way instead.”

And that’s all to the good. A baby writer should take inspiration from her predecessors, but also find ways to tell her own stories in her own way.

I’ve talked about the problems in the various reread posts: The times when the plot falls into a chasm of “What in the name of—?”; the twists that gave me whiplash; the character shifts that just did not make sense. And of course there’s the big one: the lack of fully rounded, credible female characters.

That last is all too much of its time. The feminist movements that were just really getting going when these books were written do not appear to have made any kind of dent, but more than forty years later, we can really see the shifts in attitudes and expectations.

Women in the post-Fifties world were appendages. They existed to serve men. Their lives and concerns didn’t matter, except insofar as they impinged on Important Male Things. Hence the silly, flighty servants; the evil or misguided sorceresses; the queen who could do no right; and even the Love Interest whose sole purpose for her husband was to produce a son who could conveniently be abducted, and for the hero was to look beautiful, be mysterious, and offer a chance for angsting about Honor. Because a woman has to be owned by a man, and someone else owns this one. Until he’s conveniently disposed of. Then Our Hero can own her instead.

There still are legions of men writing books with women as objects and trophies, for whom the female world is completely invisible except when it intersects the male world. But in fantasy, at least, the tide has long since turned.

The male characters are dated to a degree as well, though not so badly. The villains have few redeeming features, but they’re fun in a campy costume-drama way. The good guys have such panache, such sweep and swash. And oh, they’re pretty. They’re straight out of the movies.

Of course now we roll our eyes at Morgan’s utter self-absorption, but while he hasn’t held up so well, the supporting characters are lovely. Kelson is both a believable child (especially in his awkwardness around women) and a heroic boy-king, and Duncan and Derry are amazingly well-rounded, complex, sympathetic characters.

The ecclesiastical characters are notable I think for the way in which they’re depicted as both human beings and men of the Church. They operate on all sides of the good-to-evil spectrum, and there’s a certain sense of, not ordinariness, but of completely belonging to this world. The Church is an integral part of everyone’s life. It’s real, it’s strong, and it matters. And it’s not either monolithic Good or monolithic Bad.

So much of our fictional medievalism is distorted through a lens of Protestantism and the Reformation, slanted even further through Victorian anti-Catholicism. The depiction of actual medieval attitudes toward the Church is remarkably rare. The pervasiveness of it; the acceptance of its rightness, even while individual clerics and their dogma may be twisted or wrong.

This is not a secular world. It’s hard for moderns to understand this, especially modern Americans. Even those raised in very religious environments are used to living in a culture that they perceive, rightly or wrongly, as not innately religious. Separation of Church and state was a radical idea when the US was first founded, but it’s become The Way Things Are.

At the same time, Kurtz’s Church is more High Anglican than Roman. There’s no Pope to get in the way of kings and synods appointing bishops and decreeing Interdicts. Her world is not truly medieval in terms of technology (and outfits); it’s closer to Tudors than Plantagenets. But there’s been no Reformation, and there are no Protestants. Everyone buys into Church rule and dogma, even the oppressed and religiously persecuted Deryni. The question is not whether the Church is wrong or bad, but whether Deryni can be a part of it.

Most modern fantasy slides around the issue of organized religion in general. Kurtz goes at it head-on, builds her magical system around its ritual, and grounds her world deeply in its structure and beliefs. It’s a deeply felt, deeply internalized worldview, and there’s nothing else quite like it.

It’s not all high heroism, either. As easily and obliviously as Morgan manipulates humans, he still has the occasional moral dilemma. Duncan has a genuine conflict between not only his Deryniness and his religious vocation, but his religious vocation and his position as the last surviving heir of a duke. The latter gets rather drowned in the former, but it’s there. It exists.

And then there’s Kelson, who is young enough to be a true idealist, but mature enough, and smart enough, to know that he can’t always do the ethical thing and still be an effective king. This all comes to a head in the surprise twisty ending of High Deryni, when everything we thought we knew turns out to be off by an inch or a mile, and the last big magical blowout is roundly spiked by the completely unknown and unsuspected double agent in Wencit’s camp.

As one of the commenters last week observed, we never really get to know Stefan Coram, and yet he’s one of the most important characters in the whole trilogy. He gives his life to hand total victory to Kelson, on both the human and the Deryni sides. He comes out of nowhere and boom, it’s over.

I’m still not sure how I feel about that. It feels like a letdown, and clearly Kelson agrees. It’s quite a bit like cheating. There’s no solid payoff for this lengthy and verbose book, or for the series. Mostly it seems we’re here for the descriptions and the outfits, and we get some swashes buckled, and Morgan finally meets The One He’s Meant To Love, but. And but.

Even as wordy and rambly as this volume is compared to the other two—which are much more tightly and coherently written—it feels a bit thin at the end. We learn a lot about the Deryni underground, which doesn’t seem to be underground except in Gwynedd, and we get answers to some ongoing questions, such as the identity of the mysterious and helpful apparition of not!Camber. We get some dramatic Derry torture and some spectacular mustache-twirling on the part of the villains.

What we don’t get is an ending that allows Morgan and Kelson some real agency. Deryni manipulate humans over and over again. Humans with any approximation of agency are always either killed off or given Deryni powers or both.

I don’t know that I ever wanted to live in this world. There’s no real role for women, for one thing—even the ladies of the Council are ciphers. For another, unless you’re Deryni, you really don’t have much to live for. We’re told over and over again that humans persecute Deryni, but we never really see it. We see humans wiping out human towns and armies, but when they’re torturing our heroes, they’re using Deryni drugs or demonstrating supernatural powers. And then at the end, humans don’t matter at all. It’s Deryni, and Deryni-powered humans, all the way.

At the time I mostly bitched about the prose, which was serviceable in the first two books and overblown in the third, and I wanted something more, I wasn’t totally sure what, in the world and the characters. I didn’t consciously set out to give the humans greater agency, and I never stopped to think about making the women, you know, human. The fact that it happened when I tried writing my own medievalist fantasy was pretty much subliminal.

But there’s still something about these books. They’re compulsively readable now as they were then. The male characters are lively and engaging, and they feel remarkably real, even with their (not always intentional) faults. I had a grand time with the reread. I’m glad I did it, and I’m happy that the books hold up so well. I still love them, even if I recognize that they’re far from perfect. They’re still heart books.

Next week I’ll be moving on to Camber of Culdi. This series didn’t sink as deeply into my psyche as the first three did, but I enjoyed them and I appreciated the light they shed on the history and the mysteries of the Morgan books. I’ll be interested to see how they come across, all these years later.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, a medieval fantasy that owed a great deal to Katherine Kurtz’s Deryni books, appeared in 1985. Her most recent novel, Forgotten Suns, a space opera, was published by Book View Café in 2015, and she’s currently completing a sequel. In between, she’s written historicals and historical fantasies and epic fantasies, some of which have been reborn as ebooks from Book View Café. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed spirit dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.