“Red as Blood and White as Bone” by Theodora Goss is a dark fantasy about a kitchen girl obsessed with fairy tales, who upon discovering a ragged woman outside the castle during a storm, takes her in—certain she’s a princess in disguise.

I am an orphan. I was born among these mountains, to a woodcutter and his wife. My mother died in childbirth, and my infant sister died with her. My father felt that he could not keep me, so he sent me to the sisters of St. Margarete, who had a convent farther down the mountain on which we lived, the Karhegy. I was raised by the sisters on brown bread, water, and prayer.

This is a good way to start a fairy tale, is it not?

When I was twelve years old, I was sent to the household of Baron Orso Kalman, whose son was later executed for treason, to train as a servant. I started in the kitchen, scrubbing the pots and pans with a brush, scrubbing the floor on my hands and knees with an even bigger brush. Greta, the German cook, was bad-tempered, as was the first kitchen maid, Agneta. She had come from Karberg, the big city at the bottom of the Karhegy—at least it seemed big, to such a country bumpkin as I was then. I was the second kitchen maid and slept in a small room that was probably a pantry, with a small window high up, on a mattress filled with straw. I bathed twice a week, after Agneta in her bathwater, which had already grown cold. In addition to the plain food we received as servants, I was given the leftovers from the baron’s table after Greta and Agneta had picked over them. That is how I first tasted chocolate cake, and sausage, and beer. And I was given two dresses of my very own. Does this not seem like much? It was more than I had received at the convent. I thought I was a lucky girl!

I had been taught to read by the nuns, and my favorite thing to read was a book of fairy tales. Of course the nuns had not given me such a thing. A young man who had once stayed in the convent’s guesthouse had given it to me, as a gift. I was ten years old, then. One of my duties was herding the goats. The nuns were famous for a goat’s milk cheese, and so many of our chores had to do with the goats, their care and feeding. Several times, I met this man up in the mountain pastures. (I say man, but he must have been quite young still, just out of university. To me he seemed dreadfully old.) I was with the goats, he was striding on long legs, with a walking stick in his hand and a straw hat on his head. He always stopped and talked to me, very politely, as he might talk to a young lady of quality.

One day, he said, “You remind me of a princess in disguise, Klara, here among your goats.” When I told him that I did not know what he meant, he looked at me in astonishment. “Have you never read any fairy tales?” Of course not. I had read only the Bible and my primer. Before he left the convent, he gave me a book of fairy tales, small but beautifully illustrated. “This is small enough to hide under your mattress,” he said. “Do not let the nuns see it, or they will take it from you, thinking it will corrupt you. But it will not. Fairy tales are another kind of Bible, for those who know how to read them.”

Years later, I saw his name again in a bookstore window and realized he had become a poet, a famous one. But by then he was dead. He had died in the war, like so many of our young men.

I followed his instructions, hiding the book under my mattress and taking it out only when there was no one to see me. That was difficult at the convent, where I slept in a room with three other girls. It was easier in the baron’s house, where I slept alone in a room no one else wanted, not even to store turnips. And the book did indeed become a Bible to me, a surer guide than that other Bible written by God himself, as the nuns had taught. For I knew nothing of Israelites or the building of pyramids or the parting of seas. But I knew about girls who scrubbed floors and grew sooty sleeping near the hearth, and fish who gave you wishes (although I had never been given one), and was not Greta, our cook, an ogress? I’m sure she was. I regarded fairy tales as infallible guides to life, so I did not complain at the hard work I was given, because perhaps someday I would meet an old woman in the forest, and she would tell me that I was a princess in disguise. Perhaps.

The day on which she came was a cold, dark day. It had been raining for a week. Water poured down from the sky, as though to drown us all, and it simply did not stop. I was in the kitchen, peeling potatoes. Greta and Agneta were meeting with the housekeeper, Frau Hoffman, about a ball that was to take place in three days’ time. It would celebrate the engagement of the baron’s son, Vadek, to the daughter of a famous general, who had fought for the Austro-Hungarian emperor in the last war. Prince Radomir himself was staying at the castle. He had been hunting with Vadek Kalman in the forest that covered the Karhegy until what Greta called this unholy rain began. They had been at school together, Agneta told me. I found it hard to believe that a prince would go to school, for they never did in my tales. What need had a prince for schooling, when his purpose in life was to rescue fair maidens from the dragons that guarded them, and fight ogres, and ride on carpets that flew through the air like aeroplanes? I had never in my life seen either a flying carpet or an aeroplane: to me, they were equally mythical modes of transportation.

I had caught a glimpse of the general’s daughter when she first arrived the day before, with her father and lady’s maid. She was golden-haired, and looked like a porcelain doll under her hat, which Agneta later told me was from Paris. The lady’s maid had told Frau Hoffman, who had told Greta, and the news had filtered down even to me. But I thought a Paris hat looked much like any other hat, and I had no interest in a general’s daughter. She did not have glass slippers, and I was quite certain she could not spin straw into gold. So what good was she?

I was sitting, as I have said, in the kitchen beside the great stone hearth, peeling potatoes by a fire I was supposed to keep burning so it could later be used for roasting meat. The kitchen was dark, because of the storm outside. I could hear the steady beating of rain on the windows, the crackling of wood in the fire. Suddenly, I heard a thump, thump, thump against the door that led out to the kitchen garden. What could it be? For a moment, my mind conjured images out of my book: a witch with a poisoned apple, or Death himself. But then I realized it must be Josef, the under-gardener. He often knocked on that door when he brought peas or asparagus from the garden and made cow-eyes at Agneta.

“A moment,” I cried, putting aside the potatoes I had been peeling, leaving the knife in a potato near the top of the basket so I could find it again easily. Then I went to the door.

When I pulled it open, something that had been leaning against it fell inside. At first I could not tell what it was, but it moaned and turned, and I saw that it was a woman in a long black cloak. She lay crumpled on the kitchen floor. Beneath her cloak she was naked: her white legs gleamed in the firelight. Fallen on the ground beside her was a bundle, and I thought: Beggar woman. She must be sick from hunger.

Greta, despite her harshness toward me, was often compassionate to the beggar women who came to our door—war widows, most of them. She would give them a hunk of bread or a bowl of soup, perhaps even a scrap of meat. But Greta was not here. I had no authority to feed myself, much less a woman who had wandered here in the cold and wet.

Yet there she lay, and I had to do something.

I leaned down and shook her by the shoulders. She fell back so that her head rolled around, and I could see her face for the first time. That was no cloak she wore, but her own black hair, covering her down to her knees, leaving her white arms exposed. And her white face . . . well. This was a different situation entirely. It was, after all, within my area of expertise, for although I knew nothing at all about war widows, I knew a great deal about lost princesses, and here at last was one. At last something extraordinary was happening in my life. I had waited a long time for this—an acknowledgment that I was part of the story. Not one of the main characters of course, but perhaps one of the supporting characters: the squire who holds the prince’s horse, the maid who brushes the princess’s hair a hundred times each night. And now story had landed with a thump on the kitchen floor.

But what does one do with a lost princess when she is lying on the kitchen floor? I could not lift her—I was still a child, and she was a grown woman, although not a large one. She had a delicacy that I thought appropriate to princesses. I could not throw water on her—she was already soaking wet. And any moment Greta or Agneta would return to take charge of my princess, for so I already thought of her. Finally, I resorted to slapping her cheeks until she opened her eyes—they were as deep and dark as forest pools.

“Come with me, Your Highness,” I said. “I’ll help you hide.” She stood, stumbling a few times so that I thought she might fall. But she followed me to the only place I knew to hide her—my own small room.

“Where is . . .” she said. They were the first words she had said to me. She looked around as though searching: frightened, apprehensive. I went back to the kitchen and fetched her bundle, which was also soaked. When I handed it to her, she clutched it to her chest.

“I know what you are,” I said.

“What . . . I am? And what is that?” Her voice was low, with an accent. She was not German, like Frau Hoffman, nor French, like Madame Francine, who did the baroness’s hair. It was not any accent I had heard in my short life.

“You are a princess in disguise,” I said. Her delicate pale face, her large, dark eyes, her graceful movements proclaimed who she was, despite her nakedness. I, who had read the tales, could see the signs. “Have you come for the ball?” What country did you come from? I wanted to ask. Where does your father rule? But perhaps that would have been rude. Perhaps one did not ask such questions of a princess.

“Yes . . . Yes, of course,” she said. “What else would I have come for?”

I gave her my nightgown. It came only to her shins, but otherwise fitted her well enough, she was so slender. I brought her supper—my own supper, it was, but I was too excited to be hungry. She ate chicken off the bone, daintily, as I imagined a princess would. She did not eat the potatoes or cabbage—I supposed they were too common for her. So I finished them myself.

I could hear Greta and Agneta in the kitchen, so I went out to finish peeling the potatoes. Agneta scolded me for allowing the fire to get low. There was still meat to roast for the baron’s supper, while Greta made a cream soup and Agneta dressed the cucumber salad. Then there were pots and pans to clean, and the black range to scrub. All the while, I smiled to myself, for I had a princess in my room.

I finished sweeping the ancient stone floor, which dated back to Roman times, while Greta went on about what we would need to prepare for the ball, how many village women she would hire to help with the cooking and baking for that night. And I smiled because I had a secret: My princess was going to the ball, and neither Greta nor Agneta would know.

When I returned to my room, the princess was fast asleep on my bed, under my old wool blanket that was ragged at the edges. I prepared to sleep on the floor, but she opened her eyes and said, “Come, little one,” holding the blanket open for me. I crawled in and lay next to her. She was warm, and she curled up around me with her chin against my shoulder. It was the warmest and most comfortable I had ever been. I slept soundly that night.

The next day, I woke to find that she was already up and wearing my other dress.

“Today, you must show me around the castle, Klara,” she said. Had she heard Greta or Agneta using my name the night before? The door was not particularly thick. She had not told me her name, and I did not have the temerity to ask for it.

“But if we are caught,” I said, “we will be in a great deal of trouble!”

“Then we must not be caught,” she said, and smiled. It was a kind smile, but there was also something shy and wild in it that I did not understand. As though the moon had smiled, or a flower.

“All right,” I said. I opened the door of my room carefully. It was dawn, and light was just beginning to fall over the stones of the kitchen, the floor and great hearth. Miraculously, the rain had stopped overnight. Greta and Agneta were—where? Greta was probably still snoring in her nightcap, for she did not rise until an hour after me, to prepare breakfast. And Agneta, who also rose at dawn, was probably out fetching eggs and vegetables from Josef. She liked to take her time and smoke a cigarette in the garden. None of the female servants were allowed to smoke in the castle. I had morning chores to do, for there were more potatoes to peel for breakfast, and as soon as Agneta returned, I would need to help her make the mayonnaise.

But when would I find such a good opportunity? The baron and his guests would not be rising for hours, and most of the house servants were not yet awake. Only the lowest of us, the kitchen maids and bootblack, were required to be up at dawn.

“This way,” I said to my princess, and I led her out of the kitchen, into the hallways of the castle, like a great labyrinth. Frightened that I might be caught, and yet thrilled at the risk we were taking, I showed her the front hall, with the Kalman coat of arms hanging from the ceiling, and then the reception room, where paintings of the Kalmans and their horses stared down at us with disapproval. The horses were as disapproving as their masters. I opened the doors to the library, to me the most magical room in the house—two floors of books I would never be allowed to read, with a spiral staircase going up to a balcony that ran around the second floor. We looked out the windows at the garden arranged in parterres, with regular paths and precisely clipped hedges, in the French style.

“Is it not very grand?” I asked.

“Not as grand as my house,” she replied. And then I remembered that she was a princess and likely had her own castle, much grander than a baron’s.

Finally, I showed her the ballroom, with its ceiling painted like the sky and heathen gods and goddesses in various states of undress looking down at the dancers below.

“This is where you will dance with Prince Radomir,” I said.

“Indeed,” she replied. “I have seen enough, Klara. Let us return to the kitchen before you get into trouble.”

As we scurried back toward the kitchen, down a long hallway, we heard voices coming from one of the rooms. As soon as she heard them, the princess put out her hand so I would stop. Softly, she stepped closer to the door, which was partly open.

Through the opening, I could see what looked like a comfortable parlor. There was a low fire in the hearth, and a man was sprawled on the sofa, with his feet up. I moved a few inches so I could see his face—it was Vadek Kalman.

“We’ll miss you in Karelstad,” said another man, sitting beyond where I could see him. “I suppose you won’t be returning after the wedding?”

Had they gotten up so early? But no, the baron’s son was still in evening dress. They had stayed up all night. Drinking, by the smell. Drinking quite a lot.

“And why should I not?” asked Vadek. “I’m going to be married, not into a monastery. I intend to maintain a social life. Can you imagine staying here, in this godforsaken place, while the rest of you are living it up without me? I would die of boredom, Radomir.” So he was talking to the prince. I shifted a little, trying to see the prince, for I had not yet managed to catch a glimpse of him. After all, I was only a kitchen maid. What did he look like?

“And if your wife objects? You don’t know yet—she might have a temper.”

“I don’t know a damn thing about her. She hasn’t said two words to me since she arrived. She’s like a frightened mouse, doing whatever her father the general tells her. Just the same as in Vienna. I tell you, the whole thing was put together by her father and mine. It’s supposed to be a grand alliance. Grandalliance. A damn ridiculous word . . .”

I heard the sound of glass breaking, the words “God damn it all,” and then laughter. The princess stood perfectly still beside me. She was barely breathing.

“So he thinks there’s going to be another war?”

“Well, don’t you? It’s going to be Germany this time, and Father wants to make sure we have contacts on the right side. The winning side.”

“The Reich side, eh?” said the prince. I heard laughter again, and did not understand what was so funny. “I wish my father understood that. He doesn’t want to do business with the Germans. Karel agrees with him—you know what a sanctimonious ass my brother can be. You have to, I told him. Or they’ll do business with you. And to you.”

“Well, if you’re going to talk politics, I’m going to bed,” said Vadek. “I get enough of it from my father. Looks like the rain’s finally stopped. Shall we go for a walk through the woods later today? That other wolf is still out there.”

“Are you sure you saw it?”

“Of course I’m sure. It was under the trees, in the shadows. I could swear it was watching you. Anyway, the mayor said two wolves had been spotted in the forest, a hunting pair. They’re keeping the children in at night in case it comes close to the village. You know what he said to me when I told him you had shot one of them? It’s bad luck to kill the black wolves of the Karhegy, he said. I told him he should be grateful, that you had probably saved the life of some miserable village brat. But he just shook his head. Superstitious peasant.”

“Next time, remind him that he could be put in prison for criticizing the crown prince. Things will be different in this country when I am king, Vadek. That I can tell you.”

I heard appreciative laughter.

“And what will you do with the pelt? It’s a particularly fine one—the tanner said as much, when he delivered it.”

“It will go on the floor of my study, on one side of my desk. Now I need another, for the other side. Yes, let’s go after the other wolf—if it exists, as you say.”

The princess pulled me away.

I did not like this prince, who joked about killing the black wolves. I was a child of the Karhegy, and had grown up on stories of the wolves, as black as night, that lived nowhere else in Europe. The nuns had told me they belonged to the Devil, who would come after any man that harmed them. But my friend the poet had told me they were an ancient breed, and had lived on the mountain long before the Romans had come or Morek had driven them out, leading his tribesmen on their small, fierce ponies and claiming Sylvania for his own.

Why would my princess want to marry him? But that was the logic of fairy tales: The princess married the prince. Perhaps I should not question it, any more than I would question the will of God.

She led me back down the halls—evidently, she had learned the way better than I knew it myself. I followed her into the kitchen, hoping Greta would still be asleep—but no, there she stood, having gotten up early to prepare a particularly fine breakfast for the future baroness. She was holding a rolling pin in her hand.

“Where in the world have you been, Klara?” she said, frowning. “And who gave you permission to wander away? Look, the potatoes are not yet peeled. I need them to make pancakes, and they still need to be boiled and mashed. Who the devil is this with you?”

I looked over at my princess, frightened and uncertain what to say. But as neatly as you please, she curtsied and said, “I’ve come from the village, ma’am. Father Ilvan told me you need help in the kitchen, to prepare for the ball.”

Greta looked at her skeptically. I could tell what she was thinking—this small woman with her long, dark hair and accented voice. Was she a Slav? A gypsy? The village priest was known equally for his piety and propensity to trust the most inappropriate people. He was generous to peddlers and thieves alike.

But she nodded and said, “All right, then. Four hands are faster than two. Get those potatoes peeled.”

That morning we peeled and boiled and mashed, and whisked eggs until our arms were sore, and blanched almonds. While Greta was busy with Frau Hoffman and Agneta was gossiping with Josef, I asked my princess about her country. Where had she come from? What was it like? She said it was not far, and as beautiful as Sylvania, and yes, they spoke a different language there.

“It is difficult for me to speak your language, little one,” she said. We were pounding the almonds for marzipan.

“Do you tell stories there?” I asked her.

“Of course,” she said. “Stories are everywhere, and everyone tells them. But our stories may be different from yours. About the Old Woman of the Forest, who grants your heart’s desire if you ask her right, and the Fair Ladies who live in trees, and the White Stag, who can lead you astray or lead you home . . .”

I wanted to hear these stories, but then Agneta came in, and we could not talk again about the things that interested me without her or Greta overhearing. By the time our work was done, long after supper, I was so tired that I simply fell into bed with my clothes on. Trying to stay awake although my eyes kept trying to close, I watched my princess draw the bundle she had brought with her out from the corner where I had put it. She untied it, and down came spilling a long black . . . was it a dress? Yes, a dress as black as night, floor-length, obviously a ball gown. It had been tied with its own sleeves. Something that glittered and sparkled fell out of it, onto the floor. I sat up, awake now, wanting to see more clearly.

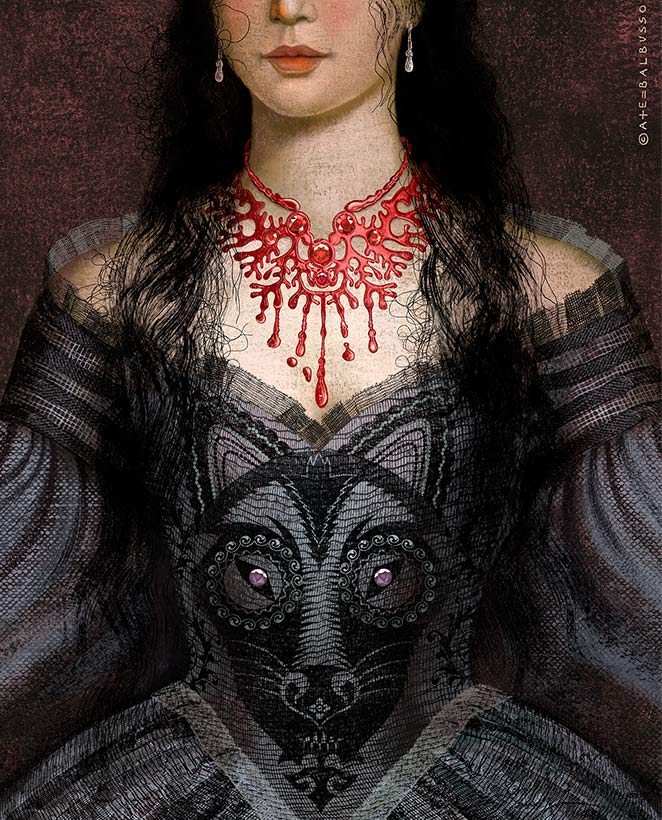

She turned and showed me what had fallen—a necklace of red beads, each faceted and reflecting the light from the single bare bulb in my room.

“Do you like it?” she asked.

“They are . . . what are they?” I had never seen such jewels, although I had read about fabulous gems in my fairy tale book. The beads were each the size of a hummingbird’s egg, and as red as blood. Each looked as though it had a star at its center. She laid the dress on my bed—I reached over and felt it, surreptitiously. It was the softest velvet imaginable. Then she clasped the necklace around her neck. It looked incongruous against the patched dress she was wearing—my second best one.

“Wait, where is . . .” She looked at the floor where the necklace had fallen, then got down on her knees and looked under the bed, then searched again frantically in the folds of the dress. “Ah, there! It was caught in a buttonhole.” She held up a large comb, the kind women used to put their hair up in the last century.

“Will you dress my hair, Klara?” she asked. I nodded. While she sat on the edge of my bed, I put her hair up, a little clumsily but the way I had seen the baroness dress her hair, which was also long, not bobbed or shingled. Finally, I put in the comb—it was as white as bone, indeed probably made of bone, ornately carved and with long teeth to catch the hair securely.

“There,” I said. “Would you like to look in a mirror?” I held up a discarded shaving glass I had found one morning on the trash heap at the bottom of the garden. I used it sometimes to search my face for any signs of beauty, but I had found none yet. I was always disappointed to find myself an ordinary girl.

She looked at herself from one side, then the other. “Such a strange face,” she said. “I cannot get used to it.”

“You’re very beautiful,” I said. And she was, despite the patched dress. Princesses are, even in disguise. That’s how you know.

“Thank you, little one. I hope I am beautiful enough,” she said, and smiled.

That night, she once again slept curled around me, with her chin on my shoulder. I dreamed that I was wandering through the forest, in the darkness under the trees. I crossed a stream over mossy stones, felt the ferns brushing against my shins and wetting my socks with dew. I found the little red mushrooms that are poisonous to eat, saw the shy, wild deer of the Karhegy, with their spotted fawns. When I woke, my princess was already up and dressed.

“Potatoes,” she said. “Your life is an endless field of potatoes, Klara.” I nodded and laughed, because it was true.

That day, we helped prepare for the ball. We were joined by Marta, the daughter of the village baker, and Anna, the groom’s wife, who had been taking odd jobs since her husband was kicked by one of the baron’s horses. He was bedridden until his leg was fully healed, and on half-salary. We candied orange and lemon peels, and pulled pastry until it was as thin as a bedsheet, then folded it so that it lay in leaves, like a book. We soaked cherries in rum, and glazed almonds and walnuts with honey. I licked some off my fingers. Marta showed us how to boil fondant, and even I was permitted to pipe a single icing rose.

All the while, we washed dishes and swept the floor, which quickly became covered with flour. My princess never complained, not once, even though she was obviously not used to such work. She was clumsier at it than I was, and if we had not needed the help, I think Greta would have dismissed her. As it was, she looked at her several times, suspiciously. How could any woman not know how to pull pastry? Unless she was a gypsy and spent her life telling fortunes, traveling in a caravan . . .

There was no time to talk that day, so I could not ask how she would get to the ball. And that night, I fell asleep as soon as my head touched the pillow.

The next day, the day of the ball, we were joined by the two upstairs maids: Katrina, who was from Karberg like Agneta, and her cousin, whose name I have forgotten. They were most superior young women, and would not have set foot in the kitchen except for such a grand occasion. What a bustle there was that day in the normally quiet kitchen! Greta barking orders and Agneta barking them after her, and the chatter of women working, although my princess did not chatter of course, but did her work in silence. We made everything that could not have been made ahead of time, whisking the béchamel, poaching fish, and roasting the pig that would preside in state over the supper room, with a clove-studded orange in its mouth. We sieved broth until it was perfectly clear, molded liver dumplings into various shapes, and blanched asparagus.

Nightfall found us prepared but exhausted. Greta, who had been meeting one last time with Frau Hoffman, scurried in to tell us that the motorcars had started to arrive. I caught a glimpse of them when I went out to ask Josef for some sprigs of mint. Such motorcars! Large and black and growling like dragons as they circled around the stone courtyard, dropping off guests. The men in black tails or military uniforms, the women in evening gowns, glittering, iridescent. How would my princess look among them, in her simple black dress?

At last all the food on the long kitchen table—the aspics and clear soup, the whole trout poached with lemons, the asparagus with its accompanying hollandaise—was borne up to the supper room by footmen. It took two of them to carry the suckling pig. Later would go the cakes and pastries, the chocolates and candied fruit.

“Klara, I need your help,” the princess whispered to me. No one was paying attention—Katrina and her cousin had already gone upstairs to help the female guests with their wraps. Marta, Anna, and Agneta were laughing and gossiping among themselves. Greta was off doing something important with Frau Hoffman. “I need to wash and dress,” she said. And indeed, she had a smear of buttery flour across one cheek. She looked as much like a kitchen maid as a princess can look, when she has a pale, serious face and eyes as deep as forest pools, and long black hair that kept escaping the braid into which she had put it.

“Of course,” I said. “There is a bathroom down the hall, beyond the water closet. No one will be using it tonight.”

No one noticed as we slipped out of the kitchen. My princess fetched her dress, and then I showed her the way to the ancient bathroom shared by the female servants, with its metal tub.

“I have no way of heating the water,” I said. “Usually Agneta boils a kettle, and I take my bath after her.”

“That’s all right,” she said, smiling. “I have never taken a bath in hot water all my life.”

What a strict regimen princesses followed! Never to have taken a bath in hot water . . . not that I had either, strictly speaking. But after Agneta had finished with it, the bathwater was usually still lukewarm.

I gave her one of the thin towels kept in the cupboard, then sat on a stool with my back to the tub, to give her as much privacy as I could while she splashed and bathed.

“I’m finished,” she said finally. “How do I look, little one?”

I turned around. She was wearing the black dress, as black as night, out of which her shoulders and neck rose as though she were the moon emerging from a cloud. Her black hair hung down to her waist.

“I’ll put it up for you,” I said. She sat on the stool, and I recreated the intricate arrangement of the other night, with the white comb to hold it together. She clasped the necklace of red beads around her neck and stood.

There was my princess, as I had always imagined her: as graceful and elegant as a black swan. Suddenly, tears came to my eyes.

“Why are you crying, Klara?” she asked, brushing a tear from my cheek with her thumb.

“Because it’s all true,” I said.

She kissed me on the forehead, solemnly as though performing a ritual. Then she smiled and said, “Come, let us go to the ballroom.”

“I can’t go,” I said. “I’m just the second kitchen maid, remember? You go . . . you’re supposed to go.”

She smiled, touched my cheek again, and nodded. I watched as she walked away from me, down the long hallway that led to other parts of the castle, the parts I was not supposed to enter. The white comb gleamed against her black hair.

And then there was washing-up to do.

It was not until several hours later that I could go to my room, lie on my bed exhausted, and think about my princess, dancing with Prince Radomir. I wished I could see her . . . and then I thought, Wait, what about the gallery? From the upstairs gallery one could look down through a series of five roundels into the ballroom. I could get up to the second floor using the back stairs. But then I would have to walk along several hallways, where I might meet guests of the baron. I might be caught. I might be sent back to the nuns—in disgrace.

But I wanted to see her dancing with the prince. To see the culmination of the fairy tale in which I had participated.

Before I could take too long to think about it, I sneaked through the kitchen and along the back hallway, to the staircase. Luckily, the second-floor hallways were empty. All the guests seemed to be down below—as I scurried along the gallery, keeping to the walls, I could hear the music and their chatter floating upward. On one side of the gallery were portraits of the Kalmans not important enough to hang in the main rooms. They looked at me as though wondering what in the world I was doing there. Halfway down the other side were the roundels, circular windows through which light shone on the portraits. I looked through the first one. Yes, there she was—easy to pick out, a spot of black in the middle of the room, like the center of a Queen Anne’s lace. She was dancing with a man in a military uniform. Was he . . . I would be able to see better from the second window. Yes, the prince, for all the other dancers were giving them space. My princess was dancing with the prince—a waltz, judging by the music. Even I recognized that three-four time. They were turning round and round, with her hand on his shoulder and her red necklace flashing in the light of the chandeliers.

Were those footsteps I heard? I looked down the hall, but they passed—they were headed elsewhere. I put my hand to my heart, which was beating too fast, and took a long breath in relief. I looked back through the window.

My princess and Prince Radomir were gone. The Queen Anne’s lace had lost its center.

Perhaps they had gone into the supper room? I waited, but they did not return. And for the first time, I worried about my princess. How would her story end? Surely she would get her happily ever after. I wanted, so much, for the stories to be true.

I waited a little longer, but finally I trudged back along the gallery, tired and despondent. It must have been near midnight, and I had been up since dawn. I was so tired that I must have taken a wrong turn, because suddenly I did not know where I was. I kept walking, knowing that if I just kept walking long enough through the castle hallways, I would eventually end up somewhere familiar. Then, I heard her voice. A door was open—the same door, I suddenly realized, where we had listened two days ago.

She was in that room—why? The door was open several inches. I looked in, carefully. She stood next to the fireplace. Beside her, holding one of her hands, was the prince. She was turned toward him, the red necklace muted in the dim light of a single lamp.

“Closer, and farther, than you can guess,” she said, looking at him, with her chin raised proudly.

“Budapest? Perhaps you come from Budapest. Or Prague? Do you come from Prague? Tell me your name. If you tell me your name, I’ll wager you I can guess where you come from in three tries. If I do, will I get a kiss?”

“And if you don’t?”

“Then you’ll get a kiss. That’s fair, isn’t it?”

He drew her to him, circling her waist with his arm. She put her arm around his neck, so that they stood clasped together. He still held one of her hands. It was a private moment, and I felt that I should go—but I could not. In my short life, I had never been to a play, but I felt as audience members feel, having come to a climactic moment. I held my breath.

“My name is meaningless in your language,” she said. He laughed, then leaned down and kissed her on the lips. They stood there by the fireplace, his lips on hers, and I thought, Yes, this is how a fairy tale should end.

I sighed, although without making a noise that might disturb them. Then with the arm that had been around his neck, she reached back and took the intricately carved comb out of her hair, so that it tumbled down like nightfall. With a swift motion, she thrust the sharp teeth of the comb into the side of his neck.

The prince threw back his head and screamed, like an animal in the forest. He stumbled back, limbs flailing. There was blood down his uniform, almost black against the red of his jacket. I was so startled that for a moment I did nothing, but then I screamed as well, and those screams—his maddened with pain, mine with fear—echoed down the halls.

In a moment, a footman came running. “Shut up, you,” he said when he saw me. But as soon as he looked into the room, his face grew pale, and he began shouting. Soon there were more footmen, and the baron, and the general, and then Father Ilvan. Through it all, my princess stood perfectly still by the fireplace, with the bloody comb in her hand.

When they brought the prince out on a stretcher, I crouched by the wall, but no one was paying attention to me. His head was turned toward me, and I saw his eyes, pale blue. Father Ilvan had not yet closed them.

They led her out, one footman on each side, holding her by the upper arms. She was clutching something. It looked like part of her dress, just as black, but bulkier. She did not look at me, but she was close enough that I could see how calm she was. Like a forest pool—deep and mysterious.

Slowly, I walked back to the kitchen. In my room, I drew up my knees and hugged them, then put my chin on my knees. The images played in my head, over and over, like a broken reel at the cinema: him bending down to kiss her, her hand drawing the comb out of her hair, the sharp, quick thrust. I had no way of understanding them. I had no stories to explain what had happened.

At last I fell asleep, and dreamed those images over and over, all night long.

In the morning, there was breakfast to prepare. As I fried sausages and potatoes, I heard Greta tell Agneta what had happened. She had heard it from Frau Hoffman herself: A foreign spy had infiltrated the castle. At least, she was presumed to be a foreign spy, although no one knew where she came from. Was she Slovakian? Yugoslavian? Bulgarian? Why had she wanted the prince dead?

She would not speak, although she would be made to speak. The baron had already telephoned the Royal Palace, and guards had been dispatched to take her, and the body of the prince, to Karelstad. They would arrive sometime that afternoon. In the meantime, she was locked in the dungeon, which had not held prisoners for a hundred years.

After breakfast, the baron himself came down to question us. The servants had been shown a sketch of a small, pale woman with long black hair, made by Father Ilvan. Katrina had identified her as one of the village women who had helped in the kitchen, in preparation for the ball. Why had she been engaged?

Because Father Ilvan had sent her, said Greta. But Father Ilvan had no knowledge of such a woman. Greta and Agneta were told to pack their bags. What had they been thinking, allowing a strange woman to work in the castle, particularly when the crown prince was present? If they did not leave that day, they would be put in the dungeon as well. And no, they would not be given references. I was too frightened to speak, to tell the baron that I had been the one to let her in. No one paid attention to me—I was too lowly even to blame.

By that afternoon, Marta, the baker’s daughter, was the new cook, and I was her kitchen maid. In two days, I had caused the death of the prince and gotten promoted.

“Klara,” she said to me, “I have no idea how we are to feed so many people, just the two of us. And Frau Hoffman says the royal guards will be here by dinnertime! Can you imagine?”

Then it was now or never. In an hour or two, I would be too busy preparing dinner, and by nightfall my princess—my spy?—would be gone, taken back to the capital for trial. I was frightened of what I was about to do, but felt that I must do it. In my life, I have often remembered that moment of fear and courage, when I took off my apron and sneaked out the door into the kitchen garden. It was the first moment I chose courage over fear, and I have always made the same choice since.

The castle had, of course, been built in the days before electric lights. Even the dungeon had windows. Once, Josef had shown them to me, when I was picking raspberries for a charlotte russe. Holding back the raspberry canes, he had said, “There, you see, little mouse, is the deep dark dungeon of the castle!” Although as far as I could tell it was just a bare stone room, with metal staples in the walls for chains. From the outside, the windows were set low into the castle wall, but from the inside they were high up in the wall of the dungeon—high enough that a tall man could not reach them. And they were barred.

It was late afternoon. Josef and the gardener’s boy who helped him were nowhere in sight. I crawled behind the raspberry canes, getting scratched in the process, and looked through one of the barred windows.

She was there, my princess. Sitting on the stone floor, her black dress pooled around her, black hair hanging down, still clutching something black in her arms. She was staring straight ahead of her, as though simply waiting.

“Princess!” I said, low in case anyone should hear. There must be guards? But I could not see them. The dungeon door was barred as well. There was no way out.

She looked around, then up. “Klara,” she said, and smiled. It was a strange, sad smile. She rose and walked over to the window, then stood beneath it, looking up at me, her face pale and tired in the dim light. Then I could see what she had been clutching: a wolf pelt, with the four paws and eyeless head hanging down.

“Why?” I asked. And then, for the first time, I began to cry. Not for Prince Radomir, but for the story. Because it had not been true, because she had allowed me to believe a lie. Because when Greta said she was a foreign spy, suddenly I had seen life as uglier and more ordinary than I had imagined, and the realization had made me sick inside.

“Klara,” she said, putting one hand on the wall, as far up as she could reach. It was still several feet below the window. “Little one, don’t cry. Listen, I’m going to tell you a story. Once upon a time—that’s how your stories start, isn’t it? Quietly, so the guards won’t hear. They are around the corner, having their dinners. I can smell the meat. Once upon a time, there were two wolves who lived on the Karhegy. They were black wolves, of the tribe that has lived on the mountain since time out of mind. The forest was their home, dark and peaceful and secure. There they lived, there they hoped to someday raise their children. But one day, a prince came with his gun, and he shot one of the wolves, who was carried away by the prince’s men for his fine pelt. The other wolf, who was his mate, swore that she would kill the prince.”

I listened intently, drying my face with the hem of my skirt.

“So she went to the Old Woman of the Forest and said, ‘Grandmother, you make bargains that are hard but fair. I will give you anything for my revenge.’ And the Old Woman said, ‘You shall have it. But you must give me your beautiful black pelt, and your dangerous white teeth, and the blood that runs in your body. For such a revenge, you must give up everything.’ And the wolf agreed. All these things she gave the Old Woman, who fashioned out of them a dress as black as night, and a necklace as red as blood, and a comb as white as bone. The old woman gave them to the wolf and said, ‘Now our bargain is complete.’ The wolf took the bundle the Old Woman had given her and stumbled out of the forest, for it was difficult walking on only two legs. On a rainy night, she made her way to the castle where the prince was staying. And the rest of the story, you know.”

I stared down at her, not knowing what to say. Should I believe it? Or her? Common sense told me that she was lying, that she was a foreign spy and I was a fool. But then, I have never had much common sense. And that, too, has stood me in good stead.

“Klara, put your hand through the bars,” she said.

I hesitated, then did as I was told.

She put the pelt down on the floor beside her, carefully as though it were a child, then unclasped the necklace of red beads. “Catch!” she said, and threw it up to me. I caught it—and then I heard boots echoing down the corridor. “Go now!” she said. “They’re coming for me.” I drew back my hand with the necklace in it and crawled away from the window. The sun was setting. It was time for me to return to the kitchen and prepare dinner. No doubt Marta was already wondering where I was.

When I got back to the kitchen, I learned that the royal guards had arrived. But they were too late—using the metal staples on the walls, my princess had hanged herself by her long black hair.

When I was sixteen, I left the baron’s household. By that time, I was as good a cook as Marta could teach me to be. I knew how to prepare the seven courses of a formal dinner, and I was particularly skilled in what Marta did best: pastry. I think my pâte à choux was as good as hers.

In a small suitcase, I packed my clothes, and my fairy tale book, and the necklace that my wolf-princess had given me, which I had kept under my mattress for many years.

Perhaps it was not wise, moving to Karelstad in the middle of the German occupation. But as I have said, I am deficient in common sense—the sense that keeps most people safe and out of trouble. I let bedraggled princesses in out of the rain. I pack my suitcase and move to the capital with only a fortnight’s wages and a reference from the baroness. I join the Resistance.

Although I did not know it, the café where I worked was a meeting-place for the Resistance. One of the young men who would come to the café, to drink coffee and read the newspapers, was a member. He had long hair that he did not wash often enough, and eyes of a startling blue, like evening in the mountains. His name was Antal Odon, and he was a descendent of the nineteenth-century poet Amadeo Odon. He would flirt with me, until we became friends. Then he did not flirt with me any longer, but spoke with me solemnly, about Sylvanian poetry and politics. He had been at the university until the Germans came. Then, it no longer seemed worthwhile becoming a literature professor, so he had left. What was he doing with himself now, I asked him?

It was he who first brought me to a meeting of the Resistance, in the cellar of the café where I worked. The owner, a motherly woman named Malina who had given me both a job and a room above the café, told us about Sylvanians who had been taken that week—both Jews and political prisoners. The next day, I went to a jeweler on Morek Stras, with my necklace as red as blood. How much for this? I asked him. Are these beads worth anything?

He looked at them through a small glass, then told me they would be worth more individually. Indeed, in these times, he did not know if he could find a purchaser for the entire necklace. He had never seen such fine rubies in his life.

One by one, he sold them off for me, often to the wives of German officers. Little did they know that they were funding the Resistance. I kept only one of the beads for myself, the smallest. I wear it now on a chain around my neck. So you can see, Grandmother, that my story is true.

As a member of the Resistance, I traveled to France and Belgium and Denmark. I carried messages sewn into my brassiere. No one suspects a young girl, if she wears high heels and red lipstick, and laughs with the German officers, and looks down modestly when they light her cigarette. Once, I even carried a message to a small town in the Swiss mountains, to a man who was introduced to me as Monsieur Reynard. He looked like his father, as far as one can tell from official portraits—one had hung in the nunnery schoolroom. I was told not to curtsy, simply to shake his hand as though he were an ordinary Sylvanian. I did not tell him, I saw your older brother die. I hope that someday you will once again return to Sylvania, as its king.

With my friend Antal, I smuggled political refugees out of the country. By then, we were more than friends . . . We hoped someday to be married, when the war was over. But he was caught and tortured. He never revealed names, so you see he died a hero. The man I loved died a hero.

When the war ended and the Russian occupation began, I did not know what to do with myself. I had imagined a life with Antal, and he was dead. But there were free classes at the university, for those who had been peasants, if you could pass the exams. I was no longer a peasant exactly, but I told the examiners that my father had been a woodcutter on the Karhegy, and I passed with high marks, so I was admitted. I threw myself into work and took my degree in three years—in Sylvanian literature, as Antal would have, if he had lived. I thought I would find work in the capital, but the Ministry of Education said that teachers were needed in Karberg and the surrounding area, so I was sent here, to a school in the village of Orsolavilag, high in the mountains. There I teach students whose parents work in the lumber industry, or at one of the hotels for Russian and Austrian tourists.

When I first returned, I tried to find my father. But I learned that he had died long ago. He had been cutting wood while drunk, and had struck his own leg with an axe. The wound had become infected, and so he had died. A simple, brutal story. So I have no one left in the world. All I have left is my work.

I teach literature and history to the children of Orsolavilag . . . or such literature and history as I am allowed. We do not teach fairy tales, which the Ministry of Education thinks are decadent. We teach stories of good Sylvanian boys and girls who learn to serve the state. In them, there are no frogs who turn into princes, no princesses going to balls in dresses like the sun, moon, and stars. No firebirds. There are no black wolves of the Karhegy, or Fair Ladies who live in trees, or White Stag that will, if you are lost, lead you home. There is no mention even of you, Grandmother. Can you imagine? No stories about the Old Woman of the Forest, from whom all the stories come.

Within a generation, those stories will be lost.

So I have come to you, whose bargains are hard but fair. Give me stories. Give me all the stories of Sylvania, so I can write them down, and so our underground press in Karberg, for which we could all be sent to a prison camp, can publish them. We will pass them from hand to hand, household to household. For this, Grandmother, I will give you what my princess gave so long ago: whatever you ask. I have little left, anyhow. My only possession of value is a single red bead on a chain, like a drop of blood.

I am a daughter of these mountains, and of the tales. Once, I wanted to be in the tales themselves. When I was young, I had my part in one—a small part, but important. When I grew older, I had my part in another kind of story. But now I want to become a teller of tales. So I will sit here, in your hut on goose legs, which sways a bit like a boat on the water. Tell me your stories, Grandmother. I am listening . . .

“Red as Blood and White as Bone” copyright © 2016 by Theodora Goss

Art copyright © 2016 by Anna & Elena Balbusso