Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

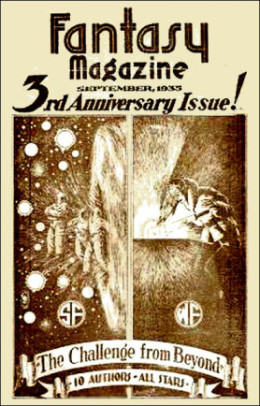

Today we’re looking at “The Challenge From Beyond,” a round robin collaboration between Lovecraft, C.L. Moore, A Merritt, Robert Howard, and Frank Belknap Long. It was commissioned by Fantasy magazine for their September 1935 issue, along with an all-star science fiction collaboration of the same title.

Spoilers ahead.

“The actual nightmare element, though, was something more than this. It began with the living thing which presently entered through one of the slits, advancing deliberately toward him and bearing a metal box of bizarre proportions and glassy, mirror-like surfaces. For this thing was nothing human—nothing of earth—nothing even of man’s myths and dreams. It was a gigantic, pale-grey worm or centipede, as large around as a man and twice as long, with a disc-like, apparently eyeless, cilia-fringed head bearing a purple central orifice.”

1. C. L. Moore

Geologist George Campbell, camping in the Canadian woods, wakes to hear a small animal scavenging his food. He reaches out of his tent for a missile, but finds a rock too interesting to toss: a clear quartz cube rounded nearly spherical by age. Embedded in its center is a disk of pale material, inscribed with wedge-shaped characters reminiscent of cuneiform. It’s too ancient to be man-made—did Paleozoic creatures create it, or did it fall from space while Earth was still molten?

Campbell tries to sleep on the mystery. When he turns off his flashlight, the cube seems to glow momentarily at its core.

2. A. Merritt

Campbell muses on the lingering glow. Did his beam waken something, making it suddenly intent on him? He experiments, focusing the flash on the cube until threads of sapphire lightning glow at its core. The embedded disk seems to grow larger, its markings shifting shape. He hears harp strings plucked by ghostly fingers.

His concentration’s broken by an animal scuffle outside the tent, predator versus prey. The natural tragedy’s over before he can investigate; he returns to find the cube’s glow fading. Evidently it needs both the light and the observer’s concentration to activate it. But to what alien end? For yes, the thing must be alien.

Conquering his trepidation, Campbell lights and stares into the cube. Again bathed in blue lightning, the disc swells into a globe, its markings come to life. The quartz walls melt into mist, the harp strings sound, and Campbell finds himself sucked into the mist and whirled toward the disc-globe.

3. H. P. Lovecraft

The globe, sapphire light, and music merge into a grey, pulsing void, through which Campbell flies with cosmic swiftness. He faints, wakes floating in impenetrable blackness, a disembodied intelligence. He realizes the cube must have hypnotized him, and that long ago he’d read about something similar.

The Eltdown Shards were unearthed from pre-Carboniferous strata in England. The occultist Winter-Hall translated them from a prehuman language known only to certain esoteric circles. According to his brochure, the Shards were created by the Yith and describe its encounter with a race of worm-like beings. These “Yekubians” conquered their native territory but can’t travel bodily across intergalactic voids. However, they do travel psychically. They launch talisman-loaded crystals out of their galaxy; a tiny percentage eventually fall on inhabited worlds. When an intelligence activates a crystal, it’s forced to exchange minds with a Yekubian investigator . Shades of Yith, except the Yekubians don’t always reverse the transfer, nor do they mass-project their minds only to self-preserve. They may exterminate races too advanced for Yekubian comfort or set up outposts using captured alien bodies, thus extending the Empire. It’s a good thing their transfer-cubes can be made only on Yekub itself.

When a cube arrived on Earth 105 million years ago, the Yith recognized the dangers and locked it away for experimentation, like a particularly vicious vial of smallpox. But 50 million years ago the cube was lost.

Campbell wakes in a blue-lit room. Narrow window-doors pierce its walls; outside, he sees alien buildings of clustered cubes. A pale gray creature half-worm, half-centipede crawls in, bearing a metal box. In its mirrored surface, Campbell glimpses his own body, and it’s that of a great worm-centipede!

Almost at once Campbell gets over the horror of his situation. What has Earth given him but poverty and repression? Freshly embodied, he can revel in new physical sensations; freed from human constraints and law, he can rule like a god! Enough of his host’s memory remains for Campbell to plan his next steps. Using a Yekubian tool as a weapon, he slaughters the scientist who approaches. He races to a temple, where an ivory sphere hovers atop an altar. This is the god of Yekub. He slaughters the priestly centipede, clambers up the altar, and seizes the sphere, which turns red as blood….

Back in the Canadian woods, Campbell’s body alters into a werebeast, amber froth dripping from its mouth. Meanwhile on Yekub, centipede Campbell bears his trophy through worshipping centipede multitudes.

Earth: The Yekubian mind cannot control the primitive instincts of Campbell’s body. It kills and devours a fox, then stumbles toward a lake.

Yekub: Centipede Campbell ascends a throne. The god-sphere energizes his body, burning away all animal dross.

Earth: A trapper finds a drowned body in the lake, its face blackened and hairy, its mouth welling with black ichor.

Yekub: The sphere god informs Campbell that no Yekubian mind can control a human body, for only millenia of slow civilization have conquered man’s bestial instincts. Campbell’s old form will raven–then, driven by death-instinct, will kill itself. No matter—purged now of all human desire, centipede Campbell rules his empire more wisely, kindly and benevolently than any human ever ruled an empire of men.

What’s Cyclopean: Frank Belknap Long, perhaps startled that his mentor neglected to leave his usual signature, describes George running “between cyclopean blocks of black masonry” with his newly acquired deity.

The Degenerate Dutch: Lovecraft gives us genocidal worms; Howard and Long promptly insist that humans are so uniquely violent and bestial that a random college professor could become god-king in less than an hour. Meanwhile, no body-switching alien can control those instincts well enough to avoid going full-on werewolf and drowning in a bog. (Except the Yith, because they’re just that awesome.)

Mythos Making: Coming in mid-story, Lovecraft wastes no time proving that in a contest of creepy body-switching genocidal alien versus creepy body-switching genocidal alien, the Yith remain masters of conflict avoidance.

Libronomicon: The Eltdown Shards, and an extremely well-informed translation of same, provide a key infodump.

Madness Takes Its Toll: George nearly matches Houdini’s record for shock-induced plot-convenient fainting.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I’ll get into the inter-author dynamics of “Challenge” in a moment. But first, I have to talk about the most important thing in this story which is that IT HAS YITH YOU GUYS HOW COME NO ONE TOLD ME. Ahem. Everyone has their favorites.

Yith who save the Earth from wormy destruction, too. Admittedly, in the process they incite wormy genocidal rage, but the odds of cold and unemotional genocide were 2/3 to begin with. That trade-off seems reasonable, especially since the rage in question is pretty impotent. Aren’t you glad to share a planet with the very nice cone-shaped beings who wipe out whole species to preserve themselves? It’s really for your own good. Besides, they have the best library.

Also, Yith would never put up with a newly arrived captive mind going on a murderous rampage. They plan for this stuff, and also don’t let Robert Howard write about them ever.

Right, so, the story. Collaborative writer games are a lot of fun. I’ve seen exactly one work as a story: the delightful Sorcery and Cecilia, born of a letter game between Pat Wrede and Caroline Stevermere. A five-way round robin is not a good set-up for narrative coherence. I hope no one’s ever gone into “Challenge” expecting anything but a close-up contrast between authorial styles, and a few rewarding moments of WTF, all of which it provides in spades.

“Challenge” starts weakly. Moore offers the basic set-up of a strange artifact. Merritt adds little but intuition that the artifact might be alien, and the conceit that attention + light = activation. But Moore’s sensuality is on full display—and without an inhumanly sexy woman in sight, just a decadent description of R&R. Merritt offers beautiful language, shifting from Moore’s academic object descriptions to “tiny fugitive lights” “like threads of sapphire lightnings.” On the other hand, it’s clear neither author particularly bothered to proofread, leading to clunkers like Merritt’s “It was alien, he knew it; not of this earth. Not of earth’s life.” Thank you, we figured out what you meant the first time.

Lovecraft kicks it up several notches, pushing the plot—or at least the worldbuilding—into high gear. For a story that he didn’t start and won’t get to finish, he tosses out a brand new species, body plan, and efficient body-switching-and-genocide strategy for universal conquest. Then he throws his new species against the Yith—created scant months before–answers the eternal question of “who’d win,” and sticks George into a worm-critter body. You can see where this would go if Lovecraft remained on task, but he’s covered that ground already in “Shadow Out of Time” and the more forgettable “Through the Gates of the Silver Key,” so he hands the thing off…

To Robert Howard, who promptly goes full Conan. I laughed out loud at the whiplash from “OH GOD THE BODY HORROR” angst to “I AM A GOD OF ADVENTURE AND RAMPAGE” delight. I also pondered George’s statement that he’s exhausted the physical possibilities of his earthly body—all that and an academic career too!

But the contrast grew grating. PSA: universal conquest and genocide begin at home. The worm-critter’s failure to anticipate violence in newly arrived captives, the unique bestiality and benevolent leadership of Homo sapiens, raised more eyebrows than chuckles.

Not that we’re looking for narrative consistency or anything—but the sharp divide brought home the degree to which this human superiority complex remained typical (and played totally straight) in speculative fiction from the earliest pulps through the Campbellian Silver Age through 90% of space opera into the modern day. For all that Lovecraft found humanity’s minor place in the universe unacceptable and horrifying, at least his fiction admitted it. No wonder cosmic horror still manages to unsettle, almost a century later.

Anne’s Commentary

My mind travels unfathomable literary distances from this story to the round robin game in Little Women, which tells more about the participants than it does about the patchwork story they concoct. The five contributors to “Challenge from Beyond” churn out a relatively coherent plot, a semi-coherent protagonist, and an amusing variety of tones and thematic slants. What’s most important with this type of collaboration, they seem to be having fun—and in the case of Lovecraft and Howard, to be deliberately lampooning themselves.

I don’t know how the collaboration came about, though some of our erudite commenters probably will! I’d guess the writers started with a title, or at least with the idea of a challenge from beyond. Moore’s task was to set the stage and create the challenge, which she did with the initium of an accidental discovery. Her protagonist is just the fellow to find a Yekubian cube. One, he’s a geologist and so realizes how old the cube must be, how impossible it could be shaped by intelligent intent. No overly rigid rationalist, he’s imaginative enough to posit prehuman makers for the cube, to envision the artifact falling from space while earth was still molten. The setting does two jobs. It gives us a bracing, earthy atmosphere to contrast with the utterly alien cube. It also isolates the protagonist, leaving no one to interfere with his fate.

The way Campbell finds the cube, eh. It’s lying right by the entrance to his tent—wouldn’t he have noticed it earlier? Like when he was crawling around pitching the tent? What about the scavenger among the tins? It’s kind of a red herring, a toss-away device to wake Campbell. But two of the other writers build on the animal detail and give it a bit of thematic importance.

Merritt picked up on the cube’s glow as the obvious route into his contribution and a serviceable starch to thicken the plot. He adds sapphire lightning and expanding disc visuals. His Campbell realizes that a combination of electric light and fixed attention is the way to activate the cube, and is curious enough to overcome instinctive qualms. Again a serviceable approach—cautious characters do not a quick thriller make. Say Campbell had tossed the cube into the woods, or worse, the lake. Either the end of the story, or Lovecraft would have had to create a whole new cube-finding protagonist.

Merritt didn’t do that to him. Instead (after a brief diversion of animal mayhem in the bushes) he started Campbell on his mental dive toward the quartz-embedded disc-globe aaaaaand—on to you, Howard! Perfect pass. Lovecraft instantly put Campbell through the usual dizzying trip through infinite chaos and out into a calm bodiless limbo conducive to info-dumping. I can imagine Lovecraft grinning as he contrived Campbell’s sudden memory: Ah! Here’s why I had a passing twinge of fear over the cube! I read about that sort of thing in the Eltdown Shards, er, that is, in the supposed translation of them by an occultist clergyman, and now that I’m floating in limbo, I’ve nothing to do but remember every detail about those worm-beings and their empire and their habit of seeding the universe with mind-transfer devices.

Only one thing could be better, and since “Challenge” was written in 1935, the same year as “Shadow Out of Time,” he seized the chance to weave the Yith into the history of our cube!

A final giggle for Lovecraft—he gets to describe a new sentient race! Realizing worms aren’t all that interesting visually, he throws in some centipede and a purple orifice and a necklace of “speaking” red spikes, and ew, yeah, scary-cool. The finish is a favorite Lovecraft moment: the protagonist realizes he’s become the monster. And faints. In fact, under Lovecraft’s care, Campbell faints three times.

Robert Howard continues the individual tropefest with gusto. The first three George Campbells remain professorial types. Howard gleefully remakes Campbell into Conan the Centipede, formerly poor and repressed and jaded with the physical pleasures of Earth, eager to try out Yekubian sensations and to make himself its king, even as “of old barbarians had sat on the thrones of lordly empires.” Rawr, enough of this slavish fainting! Campbell seizes a sufficiently blade-like tool and slaughters all bugs in his path. Entrails spill! Life is ripped out of horror-frozen priests! Ivory spheres turn blood-red in the grasp of his mighty thews!

What’s Frank Belknap Long to do with that? He’s got the closing segment, and has to make sense out of the rollicking hash, both on Yekub and on Earth. I think he pulls it off. He combines that little wild animal motif from Moore and Merritt with Howard’s version of Campbell as suddenly liberated savage. Back in the woods, Campbell’s human shell retains its animal instincts, and the Yekub usurper can’t handle them. Their shared body morphs into a werebeast, exuding ichors, and rampages to its death in the lake. On Yekub, ironically, Campbell’s lawless act of taking a god hostage burns all “animal dross” from him and makes him a benevolent ruler over the (formerly?) malevolent Yekubians—a superhumanly benevolent ruler, at that. So happy ending all around. Well, except for the drowned centipede investigator and traumatized trapper.

Whew, challenge met!

Next week, we can finish up (or at least continue) our conversation about what’s really happening in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper.” In preparation for future weeks, we’re offering a squid to anyone who can identify availability for Joanna Russ’s “My Boat” that doesn’t involve out-of-print dead trees.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint in April 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.