The people of Gaant are telepaths. The people of Enith are not. The two countries have been at war for decades, but now peace has fallen, and Calla of Enith seeks to renew an unlikely friendship with Gaantish officer Valk over an even more unlikely game of chess.

From the moment she left the train station, absolutely everybody stopped to look at Calla. They watched her walk across the plaza and up the steps of the Northward Military Hospital. In her dull gray uniform she was like a storm cloud moving among the khaki of the Gaantish soldiers and officials. The peace between their peoples was holding; seeing her should not have been such a shock. And yet, she might very well have been the first citizen of Enith to walk across this plaza without being a prisoner.

Calla wasn’t telepathic, but she could guess what every one of these Gaantish was thinking: What was she doing here? Well, since they were telepathic, they’d know the answer to that. They’d wonder all the same, but they’d know. It would be a comfort not to have to explain herself over and over again.

It was also something of a comfort not bothering to hide her fear. Technically, Enith and Gaant were no longer at war. That did not mean these people didn’t hate her for the uniform she wore. She didn’t think much of their uniforms either, and all the harm soldiers like these had done to her and those she loved. She couldn’t hide that, and so let the emotions slide right through her and away. She felt strangely light, entering the hospital lobby, and her smile was wry.

Some said Enith and Gaant were two sides of the same coin; they would never see eye to eye andwould always fight over the same spit of land between their two continents. But their differences were simple, one might say: only in their minds.

The war had ended recently enough that the hospital was crowded. Many injured, many recovering. In the lobby, Calla had to pause a moment, the scents and sounds and bustle of the place were so familiar, recalling for her every base or camp where she’d been stationed, all her years as a nurse and then as a field medic. She’d spent the whole war in places like this, and her hands itched for work. Surely someone needed a temperature taken or a dressing changed? No amount of exhaustion had ever quelled that impulse in her.

But she was a visitor here, not a nurse. Tucking her short hair behind her ears, brushing some lint off her jacket, she walked to the reception desk and approached the young woman in a khaki uniform sitting there.

“Hello. I’m here to see one of your patients, Major Valk Larn. I think all my paperwork is in order.” Speaking slowly and carefully because she knew her accent in Gaantish was rough, she unfolded said paperwork from its packet: passport, visa, military identification, and travel permissions.

The Gaantish officer stared at her. Her hair under her cap was pulled back in a severe bun; her whole manner was very strict and proper. Her tabs said she was a second lieutenant—just out of training and the war ends, poor thing. Or lucky thing, depending on one’s point of view. Calla wondered what the young lieutenant made of the mess of thoughts pouring from her. If she saw the sympathy or only the pity.

“You speak Gaantish,” the lieutenant said bluntly.

Calla was used to this reaction. “Yes. I spent a year at the prisoner camp at Ovorton. Couldn’t help but learn it, really. It’s a long story.” She smiled blandly.

Seeing the whole of that long story in an instant, the woman glanced away quickly. She might have been blushing, either from confusion or embarrassment, Calla couldn’t tell. Didn’t really matter. Whatever it was, she covered it up by examining Calla’s papers.

“Technician Calla Belan, why are you here?” The lieutenant sounded amazed.

Calla chuckled. “Really?” She wasn’t hiding anything; Valk and her worry for him were at the front of her mind.

The other Gaantish soldiers in the lobby were too polite to stare at the exchange, but they glanced over. If they really focused they could learn everything about her. They were welcome to her history. It was interesting.

“What’s in your bag?” the lieutenant said.

Some food, a couple of paperbacks for the trip, her chess set in its small pine box. Calla couldn’t help but think of it, and the woman saw it all. Calla could only smuggle in contraband if someone had put it there without her knowledge, or if she had forgotten about it.

The lieutenant’s brow furrowed. “Chess? That’s a game? May I see it?”

It still startled Calla sometimes, the way they just knew. “Yes, of course,” she said, and opened the flap of her shoulder bag. The lieutenant drew out the box, studied it. Maybe to reassure herself that it didn’t pose a threat. The lieutenant could see, through Calla, that it was just a game.

“Am I going to be able to see Major Larn?” With a glance, the lieutenant would know everything he meant to her. Calla waited calmly for her answer.

“Yes. Here. Just a moment.” The lieutenant took a card out of her drawer and filled out the information listed on it. The card attached to a clip. “Pin this to your lapel. People will still stop you, but this will explain everything. You shouldn’t have trouble. Any more trouble.” The young woman was too prim to really smile, but she seemed to be making an effort at kindness. Calla was likely the first real Enithi the young woman had ever met in person. To think, here Calla was, doing her part for the peace effort. That was a nice way of looking at it, and maybe why Valk had asked her to come.

“Go down that corridor,” the young woman directed. She consulted a printed roster on a clipboard. “Major Larn is in Ward 6, on the right.”

“Thank you.” The gratitude was genuine, and the lieutenant would see that along with everything else.

Enithi never lied to the Gaantish. This was a known, proverbial truth. There was no point to it. Through all the decades of war, Enith never sent spies—or, rather, they never told the spies they sent that they were spies. They delivered messages without telling the bearers they were messengers. Their methods of conducting espionage had become so arcane, so complex, that Gaant rarely discovered them. Both sides counted on this one truth: Enithi never bothered lying when confronted with telepaths. The Gaantish had captured thousands of Enithi soldiers, who simply and immediately confessed everything they knew. Enithi were known to be a practical people, without any shame to speak of.

Enith kept any Gaant soldiers it captured sedated, drugged to delirium, to frustrate their telepathy. The nurses who looked after them were chosen for their cheerful dispositions and generally straightforward thoughts. Calla Belan had been one of those nurses. Valk Larn had been one of those prisoners when they first met—only a lieutenant then. It had been a long time ago.

Gaantish soldiers continued staring at her as she walked down the corridor. Some men in bandages waited on benches, probably for checkups in a nearby exam room. Renovations were going on—replacing light fixtures, looked like. In all their eyes, her uniform marked her. She probably shouldn’t have worn it but was rather glad she had. Let them know exactly who she was.

On the other hand, she always felt that if the Enithi and Gaantish all took off their uniforms they would look the same: naked.

One of the workmen at the top of a ladder, pliers in hand to wire a new light, choked as she thought this, and glanced at her. A few others were blushing, hiding grins. She smiled. Another blow struck for peace.

Past several more doorways and many more stares, she found Ward 6. She paused a moment to take it in and restore her balance. The wide room held some twenty beds, all of them filled. Most of the patients seemed to be sleeping. She guessed these were serious but stable cases, needing enough attention to stay here but not so much that there was urgency. Patients had bandages at the end of stumps that had been arms or legs, gauze taped over their heads or wrapped around their chests, broken and splinted limbs. A pair of nurses was on hand, moving from bed to bed, adjusting suspended IV bottles, checking dressings. The situation’s familiarity was calming.

The nurses looked at her, then glanced at each other, and the loser of that particular silent debate came toward Calla. She waited while the man studied her badge.

“I’m here to see Major Larn,” Calla said carefully, politely, no matter that the nurse would already know. By now, Calla was thinking of nothing else.

“Yes,” the nurse said, still startled. “He’s here.”

“He’s well?” Calla couldn’t help but ask.

“He will be. He—he will be glad to see you, when he wakes up. But you should let him sleep for now.” Between Calla and Valk, how much was the nurse seeing that couldn’t be put into words?

“Oh, yes, of course. May I wait?”

The nurse nodded and gestured to a stray chair, waiting by the wall for just such a purpose.

“Thank you,” Calla said, happy to display her gratitude, though she was afraid this only confused them. They could see that Valk was more important to her than other considerations, even patriotism. They could not see why, because Calla was confused about that herself. Calla fetched the chair and looked for Valk.

And there he was, in the last bed in the row, a curtain partially pulled around him for privacy. He’d been like this the first time she’d seen him, lying on a thin hospital mattress, well-muscled arms at his sides, his face lined with the worries of a dream. More lines now, perhaps, but he was one of those men who was aging into a rather heart-stopping rough handsomeness. At least she thought so. He would laugh at her thought, then wrinkle his brow and ask her if she was thinking true.

An IV fed into his arm, a blanket lay pulled over his stomach, but it didn’t completely hide the bandage. He’d had abdominal surgery. Before settling in, she checked the chart hanging on a clipboard at the foot of the bed. She’d never really learned to read Gaantish, but could read medical charts from when she was at Ovorton and they’d put her to work. Injuries: Internal bleeding, repaired. Shrapnel in the gut. He’d been cleaned and patched up, but a touch of septicemia had set in. He was recovering well, but had been restricted to bed rest in the ward, under observation, because past experience showed that he could not be trusted to rest without close supervision. He was under mild sedation to assist in keeping him still. So yes, this was Valk.

She settled in to wait for him to wake up.

“Calla. Calla. Hey.”

She woke at her name, shook dreams and worries away, and opened her eyes to see Valk looking back. He must have been terribly weak—he only turned his head. Didn’t even try to sit up.

He was smiling. He said something too quickly and softly for her to catch.

“My Gaantish is rusty, Major.” She was surprised at the relief she felt. In her worst imaginings, he didn’t recognize her.

“I’ll always recognize you,” he said, slowly this time. He switched to Enithi, “I said, this is like the first time I saw you, in a chair near my bed.”

She felt her own smile dawn. “I wasn’t asleep then. I should know better than to fall asleep around you people.”

“They tell me the cease-fire is holding. The treaty is done. It must be, if you’re here.”

“The treaty isn’t done but the peace is holding. My diplomatic pass to see you only took a week to process.”

“Soon we’ll have tourists running back and forth.”

“Then what’ll they do with us?”

His smile was comforting. It meant the bad old days really were done. If he could hope, anyone could hope. And just like that, his smile thinned, or became thoughtful, or something. She couldn’t tell what he was thinking. Never could, and usually it didn’t bother her.

She said, “They—people have been very polite to me here.”

“Good. Then I will not need to have words with anyone. Calla—thank you for coming. I’d have come to find you, if I’d been able.”

“I worried when you told me where you were.”

“I have been rather worried myself.”

His telegram had said only two things: I would like to see you, and Bring the game if you can. A very strange message at a very strange time. Strange to anyone except her, anyway. It made perfect sense to her. She had explained it to the visa people and passport department and military attachés like this: We have a history. He had been her prisoner, then she had been his, and they had made a promise that if peace ever came they would finish the game they had started. If they finished the game it meant the peace would last.

Calla suspected that none of the Enithi officials who reviewed her request knew what to make of it, but it seemed so weird, and they were so curious, they approved it. On the Gaantish side, Valk was enough of a war hero that they didn’t dare deny the request. Out of such happenstances was a peace constructed.

She looked around—there was a bedside table on wheels that could be pulled over for meals and exams and such. Drawing the chess set from her bag, she set it on the table.

“Ah,” Valk said. He started to sit up.

“No.” She touched his shoulder, keeping him in place with as strong a thought as she could manage. This made him grin. “There’s got to be some way to raise the bed.”

She’d moved to the front of the bed to start poking around when one of the nurses came running over. “Here, I’ll do that,” he said quickly.

Calla stepped out of his way with a wry look. Gaantish hospitals didn’t have buzzers for nurses. It had driven her rather mad, back in the day. In short order, the man had the bed propped up and Valk resting upright. He seemed more himself, then.

The chess set opened into the game board, painted in black and white alternating squares, and a little tray that slid out held all the pieces, stylized carvings in stained wood. Valk leaned forward, anticipation in his gaze. “I haven’t even seen anything like this since we played back at Ovorton.”

Gaant did not have chess. They did not have any games at all that required strategy or bluffing. There was no point. Instead, they played games based on chance—dice rolls and drawn cards—or balance, pulling a single wooden block out of a stack of blocks, for example. And they never cheated.

But Calla had taught Valk chess and developed a system for playing against him. Only someone from Enith would have thought of it. The two countries had approached the war much the same way.

“I’m rusty as well. We’ll be on even footing.”

Valk laughed. They’d never been on even footing and they both knew it. But they both compensated, so it all worked out.

“I made a note of where the last game left off. Or would you rather start a new one?”

“Let’s finish the last.” He might have said it because she was thinking it, too.

She arranged the pieces the way they had been, and reminded herself how the game had gone so far. There was a lot to recall. She didn’t remember some of the details, but given the rules and given the pieces, she only had so many choices of what to do next. She considered them all.

“It was your move, I think,” she said.

He studied her rather than the board. The Gaantish didn’t have to see someone to see their thoughts—a blind Gaant was still telepathic. But looking was polite, as in any conversation. And it was intimidating, in an interrogation. This idea that they could see through you. Enithi soldiers told stories about how when a Gaantish person read your mind, it hurt. That they could inflict pain. This wasn’t true. Gaant encouraged the stories anyway, along with the ones about how any one of them could see the thoughts of every person in the world, when they couldn’t see much past the walls of a given room.

Valk was going to decide, by seeing her thoughts, what move he ought to make, what move she hoped he would, based on her knowledge and experience. He would try to deduce for himself the best choice. And then he would know, almost as soon as she did herself, how she would counter. She kept her expression still, as if that mattered. He moved a piece, and she saw her thoughts reflected back at her—it was just what she would have done, if the board had been reversed.

Next came her turn, and it was no good staring at the board, analyzing the rooks and pawns and playing out future moves in her mind. All such planning would betray her here. So, almost without looking, almost without thought, she reached, put her hand on a piece—any piece, it hardly mattered—and moved it. A bishop this time, and she only moved one square, and yet it was as if a bit of chaos had descended on the board and disrupted everything. No sane chess player would have made that move, and she herself had to pause and consider what she’d done, what new lines of play existed, and how she could possibly go forward from here.

But, and this was the point, the telepathic Valk had not been expecting what she’d just done.

Playing at random was no way to play chess, and she was sure her old teachers were turning in their graves. Unless, she would explain to them, you’re playing with a Gaantish commander. Then the joy in the game became watching him squirm.

“I am glad you are enjoying this,” Valk said.

“I am. Are you?”

“I am,” he said, looking at her. “This gives me hope.”

She had traveled here because she had nothing left. Because she was unhappy. Because her whole life had been spent in this uniform, for all the pain it had brought her, so what did she do now? She hadn’t had an answer until Valk sent that telegram.

And now he was frowning. She’d been able to keep up a good front before this.

“We are all of us wounded,” he said softly.

“It’s your move.”

He chose his piece, a pawn, a completely different move than the one she’d been thinking of, which made her next choices more interesting. This time, she took the correct one, the one she’d do if she’d been playing seriously.

“This isn’t serious?” he asked.

“I’m never serious.” Which he’d know was a lie, but he smiled anyway.

She’d taught him to play when she was his prisoner, but he asked to learn because of what he’d seen when he was her prisoner. She’d had a game running in the prison ward with one of the other nurses. They’d slip in plays between their rounds, in odd down moments, to clear their minds and pass the time. This job wasn’t real nursing, when all they had to do was administer medications, make sure no one had allergies or bad reactions to the drugs, and keep their patients muzzy-headed. Their board had been set up in Valk’s ward that day. Calla had been grinning because her opponent was about to lose, and he was studying the board with furrowed brow and deep concentration, looking for a way out.

A voice had said, “Hey. Hey. You.” He might have been speaking either Enithi or Gaantish. Hard to tell with so few words. Their handsome prisoner was waking up, calling for their attention. Because it wasn’t her turn, Calla had been the one to jump up and get her kit. They’d had trouble getting the dosage right on Valk; he had a high tolerance for the stuff. But they couldn’t have him reading minds, so she made a mark on his chart and injected more into his IV lead.

“No,” he’d protested, watching the syringe with a helpless panic. “No, please, I just want to talk—” He spoke very good Enithi.

“I’m sorry,” she said, and she really was. “We’ve got to keep you under. It’s better, really. I know you understand.”

And he did, or at least he’d see what she understood, that it wasn’t just about keeping information from him. It also kept the Gaantish prisoners safe, when otherwise they’d be outnumbered and battered by hostile thoughts. He still looked very unhappy as he sank back against the bed and his eyelids shut inexorably. As if something fragile had slipped out of his hand.

“Poor things,” Calla said, brushing a bit of lint off the man’s forehead.

“You’re very weird, Cal,” her chess partner said, finally making his move. “They’re Gaantish. You pity them?”

“I just think it must be hard, being so far from home in a place like this.”

She found out later that Valk hadn’t quite been asleep through all that.

Valk made his next move and winced, just as a nurse came over with a hypodermic syringe and vial on a tray, sensing his pain before he even knew it was there.

“No,” Valk said, putting up a hand before the nurse could set the tray down.

“You’re in pain; this will help you rest,” he said.

“But Technician Belan is here.”

“Y-yes sir.” The man went away without administering the sedative.

So much conversation didn’t need to be spoken when the participants could read each other’s minds. They would only say aloud the conclusion they had come to, or the polite niceties that opened and closed conversations. The rest was silent. Back at Ovorton it had often left her reeling, when she was meant to be working with a patient and two nearby doctors came to a decision, only ten percent of which had been spoken out loud, and they stared at her like she was some idiot child when she didn’t understand. She had learned to take delight in saying out loud, forcefully, “You have to tell me what you want me to do.” They’d often be frustrated with her, but it served them right. They could always send her back to the prisoner barracks. But they didn’t; they didn’t have enough nurses as it was. She had accepted an offer to trade the freedom of the rest of her unit for her skills—send the others home in a prisoner swap and she would work as a nurse for the Gaantish infirmary. They trusted her in the position because they would always know if she meant ill. Staying had been harder than she expected.

The nurse lingered near the game. It made Calla just a little bit nervous, like those days at the camp, surrounded by telepaths, and she the only person who hadn’t brought a spear to the war.

“This is a very complicated game,” the nurse observed, and that made Calla smile. That was why Valk told her he wanted to learn—it was very complicated. The thoughts people thought while playing it were methodical, yet rich.

“It is,” Valk said.

“May I watch?” the nurse asked.

Valk looked to Calla to answer, and she said, “Yes, you may.”

Enithi troops told awful stories about what it must be like in Gaantish prisoner camps. There’d be no privacy, no secrets. The guards would know everything about your fears and weaknesses, they could design tortures to your exact specifications, they could bribe you with the one thing that would make you break. No worse fate than being captured by Gaant and put in one of their camps.

In fact, it worked the other way around. The camps were nightmares for the guards, who spent all day surrounded by a thousand minds who were terrified, furious, hurt, lonely, angry, and depressed.

As a matter of etiquette, Gaantish people learned—the way that small children learned not to take off their pants and run around naked just anywhere—to guard their thoughts. To keep them close. To keep them calm, so they didn’t disrupt those around them. If they often seemed expressionless or unemotional, this was actually politeness, as Calla learned.

To the Gaantish, Enithi prisoners were very, very loud. The guards working the camps got hazard pay. They didn’t, in fact, torture their prisoners at all. First, they didn’t need to. Second, they wouldn’t have been able to stand it.

When her unit had been captured, processed, and sent to the camp, she had been astonished because Lieutenant Valk Larn—now Captain Larn—had been one of the officers in charge. Her shock of recognition caused every telepath in the room to stop and look at her. They would have turned back to their work soon enough—that she and Valk had encountered each other before was coincidental but maybe not remarkable. What made them continue staring: Calla revealed affection for Valk. Not outwardly, so much. She stood with the rest of her unit, stripped down to shirts and trousers, wrists hobbled, hungry and sleep-deprived. No, outwardly she’d been amazed, seeing her former patient upright and in uniform, steely and commanding as any recruitment poster. Her expression looked shocked enough that her sergeant at her side had dared to whisper, “Cal, are you okay?”

The Gaantish never asked each other how they were doing. She’d learned that back in the ward, looking after Valk. During his brief lucid moments she’d ask him how he was feeling, and he’d stare at her like she was playing a joke on him.

The emotion of affection was plain to those who could see it—everyone in a Gaantish uniform. And she was, under all that week’s pain and discomfort and unhappiness and uncertainty, almost happy to see him. She was the kind of nurse who had a favorite patient, even in a prison hospital.

He couldn’t not see her, not with every Gaantish soldier staring at her, then looking at him to see his reaction. She couldn’t hide her astonishment; she didn’t want to and didn’t try. She did realize this likely made the meeting harder for him than it did for her—whatever he thought of her, his staff would all see it. She didn’t know what he thought of her.

He merely nodded and waved the group on to continue processing, and they were washed down, given lumpy brown jumpsuits and assigned quarters. Later, she suspected he’d been the one to arrange the deal that won the rest of her unit’s freedom.

Calla had always thought it strange that people asked if prisoners were treated “well.” “Were you treated well?” No, she thought. The doors were locked. The guards all had guns. Did it matter if they had food and blankets, a roof? The food was strange, the blankets leftover from what the army used. Instead she answered, “We were not treated badly.”They were treated appropriately. War necessitated prisoners, since the alternative was slaughtering everyone on both sides, which both sides agreed was not ideal. You treated prisoners appropriately so that your own people would be treated appropriately in turn. That meant different things.

She was treated appropriately, which made it odd the day, only a week or so into her captivity, that Valk had her brought to his office alone. It wasn’t so odd that the guards hesitated or looked at either of them strangely. But she had been afraid. Helpless, afraid, everything. They left the binders around her wrists. All she could do was stand there before his desk and wonder if he was the kind of man who enjoyed hurting his prisoners, who enjoyed minds in pain. She wouldn’t have thought so, but she’d only ever known him when he was asleep and the brief waking moments when he seemed so lost and confused she couldn’t help but pity him, so what did she know?

“I won’t hurt you,” he said, after a long moment when he simply watched her, and she tried to hide her shaking. “You can believe me.” He asked her to sit. She remained standing, as he must have known she would.

“You were one of the nurses at the hospital. I remember you.”

“Not many remember their stays there.”

“I remember you. You were kind.”

She couldn’t not be. It was why she’d become a nurse. She didn’t have to say anything.

“You were playing a game. I remember—two people. A board. You enjoyed it very much. You had the most interesting thoughts.”

She didn’t have to think long to remember. Those afternoon games with Elio had been a good time. “Chess. It was chess.”

“Can you teach me to play?”

“Sir, I’d lose every single time. I’m not sure you’d enjoy the game. Not much challenge.”

“Nevertheless, I would like to learn it.”

This presented a dilemma. Could it be interpreted as cooperating with the enemy? More than she already was? He couldn’t force her. On the other hand, was this an opportunity? But for what? She was a medic, not a spy. Not that Enith even had spies. Valk gave her plenty of time to think this over, waiting patiently, not revealing if her mental arguments and counterarguments amused or irritated him.

“I don’t have a board or pieces.”

“What would you need to make them?”

She told him she would have to think about it, which would have been hilarious if she hadn’t been so tired and confused. The guards took her back to her cell, where she talked to the ranking Enithi officer prisoner about it. “Might not be a bad thing to have a friend here,” he advised.

“But he’ll know I’m faking it!” she answered.

“So?” he’d said, and he was right. Calla was what she was and it wouldn’t do any good to think differently. She asked for a square of cardboard and a black marker and did up a board, and drew rudimentary pieces on other little squares of cardboard. She’d rather have cut them out but didn’t bother asking for scissors, and no one offered, so that was that. It was the ugliest chess set that had ever existed.

Valk learned very quickly because she already knew the rules and all she had to do was think them and he learned. The strategy of it was rather more difficult to teach. He’d get this screwed-up look of concentration, and she might have understood a little bit of what attracted him to the game: There was a lot to think about, and Valk liked the challenge of so much thought coming out of one person. And yes, he always knew what moves she was planning. Which was when she started playing at random. If she could surprise herself, she could surprise him. Then she agreed to the deal to get her people released, she worked in their hospital, they played chess, and she got sick.

She could not learn to marshal her thoughts and emotions the way these people learned to as children. She tried, as a matter of survival, and only managed to stop feeling anything at all.

The diagnosis was depression—Gaant’s mental health people were very good. She, who had been so generally high-spirited for most of her life, had had no idea what was happening or how to cope and had grown very ill indeed, until it wasn’t that she didn’t want to play chess against Valk. She couldn’t. She couldn’t keep her mind on the game, couldn’t recognize the pieces by looking at them, couldn’t even think of how they moved. One day, walking in a haze between one ward and another at the hospital, she sank to the floor and stayed there. Valk was summoned. He held her hand and tried to see into her, to see what was wrong.

She didn’t remember thinking anything at the time. Only seeing the image of her hand in his and not understanding it.

He arranged for her to be part of another prisoner swap, and she went home. Before the transfer he took her aside and spoke softly. “I forget that this is all opaque to you, that you don’t know most of what’s going on around you. So, since I didn’t say it before: Thank you.”

“For what?” she’d replied. He’d looked at her blankly, because he didn’t seem to know himself. Not enough to be able to explain it, and she couldn’t see.

Others came to watch the game—drawn, Calla presumed, by the tangle of thoughts she and Valk were producing. He was getting frustrated. She was playing with the giddy abandon of the six-year-old she had been when her mother taught her the game. And now the whole room shared her fond memories, and the fact that her mother had died in one of the famines that wracked Enith when food production had been disrupted by the war. Ten years ago now. Everyone on both sides had stories like that. Let us share our stories, she thought.

“You won’t win, playing like that,” one of the observing doctors said. After half an hour of watching they probably all understood the rules completely and could play themselves. They’d have no idea how the game was really supposed to be played, however. She wasn’t playing properly at all, which was rather a lot of fun.

“No, but I may not lose,” she said.

“I’m still not sure what the point of this game is,” said a nurse, her confusion plain.

“This game, right now? The point is to annoy Major Larn,” Calla said. This got a chuckle from them—those who’d been looking after him knew him well. Valk, however, smiled at her. She had not spoken the truth, precisely. Everyone else was too polite to say anything.

“The point,” Valk said, addressing the nurse, “is to fight little wars without hurting anyone.”

And there was silence then, because yes, they all had stories.

He made his next move and took his hand away. Her gaze lit, her heart opening. Even the way she played with him, all messy and at random, a moment like this could still happen, where the board opened up as if by magic and her way was clear. Because it was her turn it didn’t matter if he knew what she was thinking, because he couldn’t do anything about it. She moved the rook, and his king was cornered.

“Check.”

It wasn’t mate. He could still get out of it. But he really was backed into a corner, because his next moves and hers would all lead back to check, and they could chase each other around the board, and it would be splendid. Neither could have planned for this.

He threw up his hands and settled back against his pillow. “I’m exhausted. You’ve exhausted me.” She laughed a gleeful, satisfied laugh.

The observers looked on. “This is how you won,” one of them said, amazed. He wasn’t talking about the game.

“No,” Calla said. “This is how we failed to lose.”

“I learned the difference from her,” Valk said, and was that a bit of pride in his tone? She might never know for certain.

Calla started resetting the board for the next game, not even realizing that meant she was having a good time. The nurse interrupted her.

“Technician Belan, the major really must rest now,” he said kindly, recognizing Calla’s eagerness when she herself didn’t.

“Oh. Of course.”

“I promise I’ll rest in just a moment,” Valk said. He was speaking to the doctors and attendants, who’d expressed a concern she couldn’t see. They drifted away because he wanted them to.

That left them studying each other; he who could see everything, and she who could only muddle through, being herself, proudly and unabashedly.

She asked, abruptly, “Do you still have that old cardboard set I made?”

“No. When Ovorton closed, I lost track of it. Probably got swept away with the trash.”

“Good,” she said. “It was very ugly.”

“I miss it,” Valk said.

“You shouldn’t. I’m glad it’s all over. So glad.”

That dark place that she barely remembered opened up, and she started crying. She had thought to pretend that none of it ever happened, and so carried around this blackness that no one could see, and it would have swallowed her up if Valk hadn’t sent that telegram. She got that message and knew it was all true, knew it had all happened, and he would be able to see her.

She scrubbed tears from her face and didn’t try to hide any of this.

“I wasn’t sure how much you remembered,” Valk said softly.

“I wasn’t sure either,” she said, laughing now. Laughing and crying. The darkness shrank.

“Are you sorry you came?”

“Oh, no. It’s just . . .” She put her hand in his and tried to explain. Discovered she couldn’t speak. She had no words. And it didn’t matter.

“That Game We Played During the War” copyright © 2016 by Carrie Vaughn

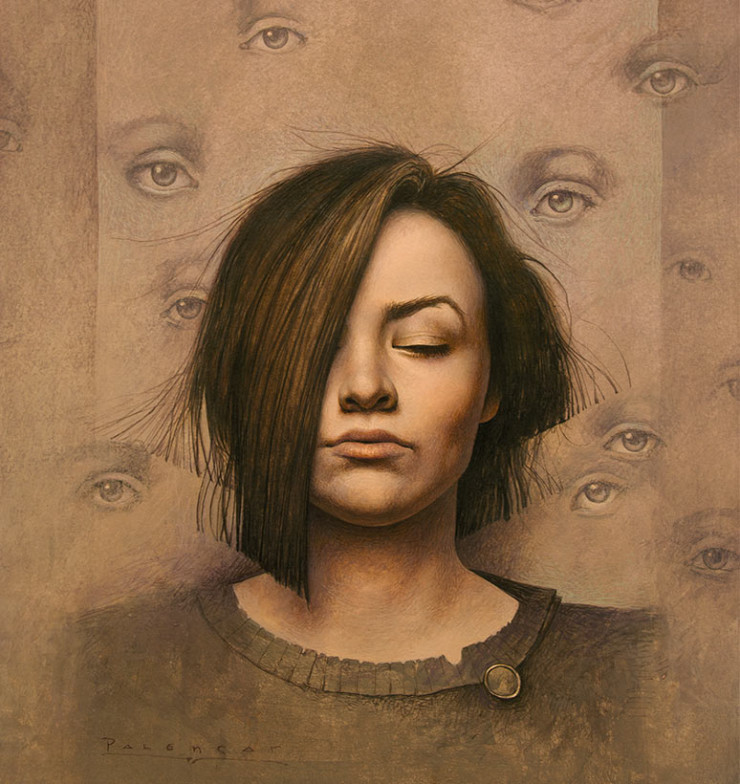

Art copyright © 2016 by John Jude Palencar