Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale is one of the best-known and most widely-read science fiction books in English. It’s taught in high schools, it’s taught in colleges, and its Wikipedia page proudly proclaims its status as one of the ALA’s 100 most frequently banned and challenged books of the Nineties. Along with 1984 and Farenheit 451, it’s one of the holy trinity of sci-fi books that every kid will most likely encounter before they’re 21. Recipient of Canada’s Governor General’s Award and the Arthur C. Clarke Award, one of the bedrocks of Atwood’s popularity, and widely considered a modern classic, it’s both a flag for, and a gateway to, sci-fi. It’s a book the community can point to and say, “See! Science fiction can be art!” and it’s a book that probably inspires a fair number of readers to either read more Atwood or to read more science fiction.

So what the hell happened to Beloved?

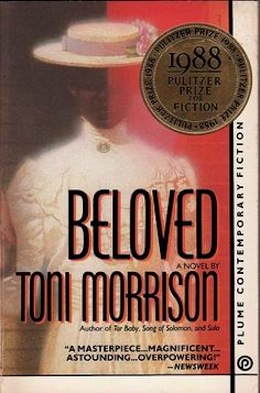

Toni Morrison’s 1987 novel, Beloved, is also on that ALA list, about eight places behind Atwood. It’s also taught in college and in high school, and it’s the book that launched Morrison into the mainstream, and won the Pulitzer Prize. It’s widely considered that Morrison’s Nobel Prize in Literature stems in large part from Beloved‘s failure to win the National Book Award.

But while Handmaid’s Tale appears on lots of “Best Books in Science Fiction” lists, I’ve rarely if ever seen Morrison’s Beloved listed as one of the “Best Books in Horror.” Beloved is considered a gateway for reading more Morrison and for reading other African-American writers, but it’s rarely held up as either a great work of horror fiction, nor do horror fans point to it as an achievement in their genre that proves horror can also be capital “a” Art. And I doubt that many high school teachers make a case for it as horror, instead choosing to teach their kids that it’s lich-a-chure.

Many claim Beloved isn’t horror. A letter to the New York Times gives the basics of the argument, then goes on to state that to consider Beloved a horror novel would do a disservice not just to the book, but to black people everywhere. Apparently, the horror label is so squalid that merely applying it to a book does actual harm not just to the book but to its readers. If horror’s going to be taken seriously (and with some of the Great American Novels considered horror, it should be) it needs to claim more books like Beloved as its own. So why doesn’t it?

Beloved, if you haven’t read it, is about Sethe, an escaped slave living in a haunted house in 1873. Another slave from her old plantation, Paul D, arrives on her doorstep and chases the ghost out of the house. Things get calm, but a few days later a young woman appears. Confused about where she came from, slightly unhinged, and knowing things about Sethe that she’s never revealed to anyone else, this girl, Beloved, could be a traumatized freed slave, or she could be the ghost of the baby Sethe murdered to keep her from being taken back into slavery. Whichever she is, Beloved’s presence soon disrupts the household, chases the healthy people away, and turns Sethe into a zombie, practically comatose with guilt over murdering her baby.

Ghost stories are about one thing: the past. Even the language we use to talk about the past is the language of horror: memories haunt us, we conjure up the past, we exorcise our demons. Beloved is a classic ghost; all-consuming, she is the sins of Sethe’s past coming not just to accuse her, but to destroy her. There has been an argument made that Beloved is just a traumatized former slave that Sethe projects this ghostly identity onto, but Morrison is unambiguous about Sethe’s identity:

“I realized that the only person really in a place to judge the woman’s action would be the dead child. But she couldn’t lurk outside the book…I could use the supernatural as a way of explaining or exploring the memory of these events. You can’t get away from this bad memory because she is here, sitting at the table, talking to you. No matter what anybody says we all know that there are ghosts.”

Literature is fun because everything is always open to multiple interpretations, but the most obvious interpretation of Beloved is that she’s a ghost. Add that to the fact that Sethe is living in a clearly haunted house at the beginning of the book, and that the book is about that most feared and despised figure in Western Civilization, the murdering mother, and that the gory and brutal institution of slavery hangs over everything, and there’s no other way to look at it: Beloved is straight-up, flat-out horror.

So why isn’t it championed more by the horror community as one of their greatest books? Sure, Morrison doesn’t run around saying that she wants to be shelved between Arthur Machen and Oliver Onions any more than Atwood hasn’t spent an infinite number of essays and interviews declaring that she doesn’t write stinky science fiction. Authorial intention has nothing to do with it. So what’s the problem?

One of the problems is that science fiction is still open to what Atwood is doing. Handmaid’s Tale engages in world-building, which is a big part of the sci-fi toolbox, and it features spec fic’s favorite trope of an underground resistance fighting a repressive, dystopian government. Beloved, on the other hand, doesn’t engage in the subject matter that seems to be preoccupying horror right now. Horror these days looks like an endless shuffling and reshuffling of genre tropes—vampires, zombies, witches, possessions, haunted houses—with novelty coming from new arrangements of the familiar pieces.

What Morrison wants to do, as she puts it, is make her character’s experiences felt. “The problem was the terror,” she said in an interview. “I wanted it to be truly felt. I wanted to translate the historical into the personal. I spent a long time trying to figure out what it was about slavery that made it so repugnant…Let’s get rid of these words like ‘the slave woman’ and ‘the slave child’ and talk about people with names, like you and like me, who were there. Now, what does slavery feel like?”

Making experience visceral and immediate is not considered the territory of horror anymore, unless you’re describing over-the-top violence. Writing to convey the immediacy of the felt experience is considered the purview of literary fiction, often dismissed as “stories where nothing happens” because the author isn’t focused on plot but on the felt experience of her characters. Horror has doubled down on its status as genre, and that kind of writing isn’t considered genre appropriate. It’s the same reason Chuck Palahniuk isn’t considered a horror writer, even though he writes about ghosts, witchcraft, body horror, and gore.

There are other reasons, of course, one of them being the fact that we’re all a bit like Sethe, trying hard to ignore the ghost of slavery that threatens to destroy us if we think about it too long. But the bigger reason, as I see it, is that horror has walked away from the literary. It has embraced horror movies, and its own pulpy 20th century roots, while denying its 19th century roots in women’s fiction, and pretending its mid-century writers like Shirley Jackson, Ray Bradbury, or even William Golding don’t exist. Horror seems to have decided that it is such a reviled genre that it wants no more place in the mainstream. Beloved could not be a better standard-bearer for horror, but it seems that horror is no longer interested in what it represents.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today; his most recent novel is Horrorstör, about a haunted Ikea, while My Best Friend’s Exorcism (which is like Beaches meets The Exorcist) will be out from Quirk Books on May 17th.