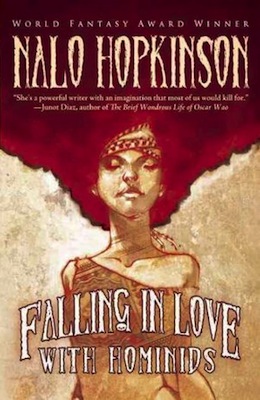

Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a space for conversation about recent and not-so-recent short stories. While we’ve had a bit of a hiatus, I’m glad to be back—and discussing a recent short story collection by a writer whose work I usually very much enjoy, Nalo Hopkinson. Falling in Love with Hominids contains one original story, “Flying Lessons,” and seventeen reprints spanning the past fifteen or so years. It’s a wide-ranging book, though as Hopkinson’s introduction argues, it is possible to trace the development of the writer’s appreciation for our human species throughout.

This, for me, was also a fascinating look back at reading I’ve done over the past several years. Five of the stories I’ve discussed here previously (“Left Foot, Right” from Monstrous Affections; “Old Habits” from Eclipse 4; and “Ours is the Prettiest” from Welcome to Bordertown; “Shift” and “Message in a Bottle” from Report From Planet Midnight). However, I’d previously read at least half in previous publication—more than usual for most collections.

As for the stories that stuck out to me the most from this delightful smorgasbord, there are a handful. I tended to appreciate the longer pieces more than the flash work, but the flash work remains interesting, often for what it reveals about Hopkinson’s pet projects and the things she finds enjoyable as a writer.

“The Easthound” (2012) is the first piece in the collection and also one of the ones that stood out most to me—both because I hadn’t encountered it before and because it’s a strong showing. As a post-apocalyptic piece, it combines a few familiar tropes: a world of children, where the coming of adulthood is also the coming of the disease that turns them into werewolf-like monsters who consume their nearest and dearest. Hopkinson combines the Peter-Pan-esque attention to staying a child as long as possible with a much darker set of notes, like the children starving themselves intentionally to slow their development. The language-game the protagonists play to occupy themselves in the fallen future is intriguing as well. Overall, I felt that the ending was a bit obvious in coming—of course it’s her twin; of course she’ll change right after—but that the emotional content of the story doesn’t suffer for it. The payoff just isn’t in the actual conclusion.

“Message in a Bottle” (2005) is perhaps my favorite of the collection—even though I’ve covered it once before, reading it again was still a pleasure. It’s multifaceted in terms of its character development, action, and emotional arc. The protagonist’s interactions—with his friends, his girlfriends, the child Kamla, and others—do the work of building a deep and often conflicted character in a very short space. I also appreciated the science fictional elements: the children aren’t actually children, and art is what fascinates the humans of the future, but not art the way that we might think of it. Kamla and Greg’s interactions in the last part of the story are spot-on in terms of the discomfort, the difficulty communicating over age and generations and social position, and the ways that people speak past each other. It feels like a solid and coherent whole as a narrative.

“The Smile on the Face” (2005), a young adult story, mixes mythology with personal growth. It’s a lighter touch after some of the previous stories, and gives the reader a glimpse into Gilla’s understanding of embodiment, race, and desire as a young woman in contemporary teen culture. It has its typical elements, particularly in the form of the rude and abusive young men who mistreat Gilla and the pretty popular girls who are willing to believe rumors about her, but it’s the other bits that make it stand out: the way that even those boys and girls aren’t stereotypes, for example. The boy who Gilla does like, Foster, still speaks with and is friends with boys who aren’t as kind—because people are complicated and difficult and fucked up, particularly as kids. The representation of friendships, desire, and self-love are the best parts, here.

“A Young Candy Daughter” (2004), one of the flash stories, is tight and compelling. In it, Hopkinson explores the “what if god were one of us” theme—by giving divine power to a young girl, daughter of a single mother, who meets our protagonist as he’s collecting donations for the Salvation Army. The child wants to give people sweets, and her mother is long-suffering in trying to help her understand how to help people without causing them harm; the protagonist is awed by the instance of a miracle in his daily life, and also by the prettiness of the mother, whom he will likely be seeing again (or so the end implies). It’s short, sweet, and a neat exploration of a familiar “what-if.”

“Snow Day” (2005) is more fun for what the author’s note tells us it is: a challenge piece where Hopkinson had to include the titles of five “Canada Reads” nominee books in the text of the story. As a story, it’s brief and treading a little close to too quaint—talking animals, aliens coming to allow us to go explore other possible worlds (even the tropical fish)—but as a prose experiment, it’s impressive. The only title I picked out was the difficult-to-manage Oryx and Crake; the rest blend in admirably well. Sometimes these little pieces are enjoyable just for what they show of an author’s style.

“Flying Lessons,” the only original story to the book, wasn’t one of my favorites though—it’s a flash piece that, so far as I can tell, is primarily illustrating the protagonist’s experience of child sexual abuse by her neighbor. I expected more from it, particularly since the topic is so intimately awful, but it doesn’t quite get there.

“Men Sell Not Such in Any Town” (2005/2015) is the closing story, another flash piece. This one deals with the work and worth of poetics, and the pulling out of emotions—an insightful note to close a short story collection on, particularly a collection that has run an emotional gamut from coming-of-age to horror. It’s another good example of the shortest form: fast, a good punch of feeling and concept.

Overall, Falling in Love with Hominids is a worthwhile collection that goes together well—and these are some of the stories I liked best. Hopkinson is a talented writer, whose interest in topics like embodiment and desire comes through in many of these stories; I appreciated reading it quite a bit.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.