Writing horror almost killed me. But it saved my life too.

It has saved my life more than once.

I’ll start with the almost-killing. Me, eleven years old and fresh from reading my first Stephen King (Pet Sematary, and even the thought of that book still brings a grin to my face). I suddenly knew what I wanted to do with my life, I wanted to be a horror writer. I wanted to tell scary stories and get paid to do it. In my eyes I was already a professional, I had five years experience under my belt after writing my first gothic masterpiece, The Little Monster Book, at six years old. I was ready to shift things up a gear, though. I wanted to write something that would terrify people.

Back then, I had a huge advantage. I believed in horror. In fact, that’s how I thought writing worked: authors didn’t just sit down and imagine things, they went out into the world and found real ghosts, and real monsters, then used those experiences as nightmare fuel. I couldn’t quite comprehend how something as good as Pet Sematary could exist without some kernel of truth at its heart, some secret, real-life horror. I was convinced that there was a conspiracy of horror authors who had witnessed the supernatural, a cabal of paranormal detectives who shared their experiences as fiction. And I wanted in. At eleven years old I didn’t just suspect that the supernatural existed, I knew that it did. I had a desperate, unshakable faith in it. That was my modus operandi, then, to find real horror and then use that experience to create a truly unforgettable story.

The other part of my plan involved a murder house, a flashlight, and my best friend Nigel.

As you can probably guess, it didn’t end well.

The house wasn’t actually a murder house, it’s just what we all called it at school—a huge, crumbling, long-abandoned English manor home about a fifteen-minute cycle ride from my house. It was at the centre of so many of the spooky stories we all told each other at school: the witch that had cursed the house, the doll maker whose creations click-clacked down the corridors, hungry for souls, the serial killer convention that met there every year, and so on. Nobody knew the truth of this place, and I believed that it was my job to find out.

After much planning, the day finally came. I told my mum I was staying at Nigel’s and Nigel told his mum he was staying at mine. We met after dark (although it was the middle of winter, so it was only about half past six), and cycled out to this house, entering through a broken window. I remember it like it was yesterday, the eye-watering stench of rat piss, the hum of the wind, and the dark, it was a kind of darkness I’d never experienced before, absolute and unfriendly.

The terror was something else too, my whole body sang with it. Because I knew, without a shadow of a doubt, that we were going to find something here. A ghost was going to flit down the hallway, caught in our flashlight beam. Or we would walk past a room and see a blood-eyed crone crouched in the corner, gnawing on somebody’s finger bones. I believed with every frantic beat of my heart that we were about to come face to face with something supernatural.

I guess that explains why it all fell apart so quickly. There was a point when we walked through a door to be greeted by the sound of a ticking clock. Cue a very ungraceful meltdown from yours truly that saw me running from the room, shrieking. Of course Nigel began to scream too, and I assumed he’d been caught by whatever malevolent force kept a grandfather clock ticking inside an abandoned house. Rather shamefully, I was running down the corridor screaming over my shoulder, “You can have him! You can have Nigel! Just let me go!” I was in such a state that I tried to exit, at speed, from the wrong window, freefalling from the mezzanine level and landing, thankfully, in mud.

Another window, another floor, another day, and my tale might have ended right there.

That experience reinforced my belief in the supernatural, although I wouldn’t venture into that haunted house—or any other—for many years. It taught me something about how powerful horror is, too. When you’re a kid and somebody tells you that there is a monster under your bed, you believe it with every piece of yourself. You assimilate that knowledge as part of your worldview, it becomes as much of a fact as anything else in your life. This can be terrifying, yes. But it’s also wonderful, isn’t it? Because if there can be a monster under your bed, then surely anything else can be possible too. And that’s what I most loved about being a child: the thought that you can walk out of your front door, and the impossible can happen.

To the eleven-year-old me, covered in my own puke and pushing my bike home that night because I was shaking too much to ride it, that experience in the house was incredible. I didn’t appreciate it for a while, of course, but those few minutes of terror (yes, I worked it out: from entering the house to me falling out the window was a little shy of eight minutes) took everything I knew was real and validated it. There had been a ghost inside that house, it had all been real. I think that’s what I remember most vividly—crashing down on my bed with a grin that made my cheeks ache. I felt as light as air, because the world was infinitely larger than it had been that morning. The horizon had been blown back. I was living in a place of limitless possibilities, and it made me laugh and laugh and laugh.

I knew then what horror meant to me. Horror was an adventure, pure and simple. Horror was that voyage into the unknown, the moment you open a door onto a brand new mystery. Horror was about accepting that there is far more to the world, to the universe, to ourselves, than the humdrum here and now. Every time I started reading—or writing—a new horror book I’d feel like the genre had picked me up and hurled me, I felt like I was spinning towards some new reality. And the beautiful thing about it was that, to me, there was a chance it could all be real.

Horror has that power no matter how old you are, I think. You could be the most rational human being in existence, but there will still be times when you read a scary story, or watch a movie, and you can feel those truths and assumptions you’ve built your whole life on start to crumble. I don’t know anyone who hasn’t felt that way at some point, lying in bed after watching a horror movie, knowing that there is no monster under the bed, knowing that there is no serial killer in the wardrobe, knowing that there is no ghost about to float down from the ceiling, but at the same time knowing for a fact that there is some terrible ghost monster in the room and you are about to die the most gruesome death of all time. Yes, it’s a horrible feeling, but it’s amazing too, because right there is that childhood you, the one who believes anything can happen. For those few minutes—or hours—until you drift into an uneasy sleep, the rules of the universe have fundamentally changed. Horror does that, it makes the impossible possible, it opens up our minds again.

The first time horror saved my life I was in my mid-twenties. I’d just gone through one of the most awful experiences of my life—I won’t go into details, but anyone who’s read the dedication to my first book, Lockdown, will know—and I was reeling. I felt like a prisoner, like I’d been locked inside this terrible reality, left to rot. I couldn’t talk to anyone, I couldn’t share it with anyone, and with each passing day I felt life shrinking around me, closing up like a fist.

I was desperate, so I did the only thing I could think of—I started to write. I knew it would help. I’d written horror stories as therapy back when I was a teenager. I don’t think there’s a more terrifying time in your life than those years. Everything is changing—your body, your mind, your friends, not to mention the way the world looks at you. Life spins in wild, wild circles and you have no control.

Writing let me slam on the brakes. Every time something scared me, every time something bad happened, every time I felt like screaming myself into oblivion, every time I felt like I was being consumed by my own rage, I wrote a story. It allowed me to channel my emotions, to focus that churning, howling mass of teenage angst into something else, something I had an element of power over. Seeing those characters battling their problems, and knowing that their solutions came from my own head, let me understand that however bad things seemed I had what it took to overcome, to survive.

Something weird happens when you write about your worst fears, even if you’re writing fiction. They stop being these unfathomably, impossibly huge things that hide in the shadowy corners of your mind. They become words, they become concrete—or, at least, paper. They lose some of their power, because when they’re laid down like that then you have the control. If you want, you can pick up those stories and tear them into pieces. You can set fire to them, flush them down the toilet. They’re yours to deal with however you want.

Back to my twenties, and I picked up a pen and just wrote. In this case, it was the Escape From Furnace books—the story of a fourteen-year-old boy, Alex, who is accused of murdering his best friend and sent to Furnace Penitentiary, the world’s worst prison for young offenders. I had no idea what I was doing, I just punched my way into this story of a boy buried alive at the bottom of the world. It was astonishing, because after just a couple of chapters I felt better. I no longer felt like I was on my own. I was right there with those guys, I was the ghost inside Alex’s cell, never seen but always present. I knew that if Alex didn’t escape this awful place, if he didn’t survive, then neither would I. Suddenly I had a war to wage, I had purpose again. I threw myself into the story in a white-hot fury, fighting tooth and nail to get us both out of Furnace. Three weeks later and, without wanting to give too much away, we both took that desperate, choking, sobbing breath of fresh air.

Writing that book saved my life. Writing horror saved my life. Partly because of the story, and the character of Alex. Furnace is a place of many horrors, but there is always hope. For me, that’s what lies at the heart of so much good horror: hope, humanity, heroism—even if that heroism is just standing up to your own, everyday life. When things are at their worst we see people at their best, we see people standing shoulder to shoulder even as the world crumbles around them. I didn’t intend to write a book about hope, but somehow, from that tragedy, this story was born. And I know, from the letters I have received, that it isn’t just my life these books have saved. Fear is contagious, but hope is too.

It goes beyond the mere story, though. There’s more to it than that. The fact that I was sitting down to write a horror story, to write about something supernatural, made me feel like I could breathe again. That fist of depression began to open, because the real world started to seem bigger. I was writing a story where literally anything could happen—I didn’t plot a single thing—and in doing so I began to feel it again, that wonderful thrill I’d had as a child, as a teenager, that reality wasn’t as solid as I’d been led to believe. For a while, the bad things I’d gone through were the complete sum of my life, they were my one, inescapable truth. But writing horror reminded me that there was so much more, that my life had infinite possibly. Once again the horizon was blown back, and in rushed the light, the air. It’s so weird, but that’s what horror is. So much darkness, so much fear, and yet this is what it brings us—the light, the air.

H orror makes us children again, in the best possible way. We’re incredibly resilient when we’re kids, because our imaginations are so vast, so powerful. They cannot be defeated. When we go through bad things, we have the emotional intelligence to recover, because we know that anything can happen. If there can be monsters under the bed then there can be miracles, too. There can be magic. There can be heroes. We understand that we can be those heroes. And yes, it’s about believing that dragons can be beaten, to paraphrase Neil Gaiman, but I think, more importantly, it’s about believing that they can exist at all. When we write horror—or read it, or watch it—we’re children again, and the world feels huge, and full of infinite possibility. When I’m lying there, waiting for the monster’s hand to creep out from under the bed, or the ghostly face to push down from the ceiling, my body once again singing with terror, I’m always grinning.

orror makes us children again, in the best possible way. We’re incredibly resilient when we’re kids, because our imaginations are so vast, so powerful. They cannot be defeated. When we go through bad things, we have the emotional intelligence to recover, because we know that anything can happen. If there can be monsters under the bed then there can be miracles, too. There can be magic. There can be heroes. We understand that we can be those heroes. And yes, it’s about believing that dragons can be beaten, to paraphrase Neil Gaiman, but I think, more importantly, it’s about believing that they can exist at all. When we write horror—or read it, or watch it—we’re children again, and the world feels huge, and full of infinite possibility. When I’m lying there, waiting for the monster’s hand to creep out from under the bed, or the ghostly face to push down from the ceiling, my body once again singing with terror, I’m always grinning.

I’m afraid of everything, but that’s a good thing. For one, it means I always have something to write about. But I’m always expecting the unexpected, too. I still have that desperate, unshaking faith in the impossible. I have that unshaking faith in horror, too, as something that’s good for the soul. I know it gets a bad rap, and I’ve had to defend my genre from countless parents over the years. But every time I hear from a fan who’s struggling, who’s going through a bad time, I give them the same advice: write a horror story. You don’t have to make it autobiographical, it doesn’t have to be a diary, just write, go wild, remind yourself how big the world is. I’m sure it doesn’t work for everyone, but more often than not the response I get is overwhelmingly positive. Writing horror is catharsis, it’s exploration, it’s a channel. It gives you ownership over your fears, some control over your life. It gives you light, and air, and hope. It makes the impossible possible, and isn’t that what we all need, sometimes? Because when you believe the impossible of the world, of the universe, then you start to believe the impossible of yourself, too.

And that’s when the true magic happens.

Oh, and for those who were wondering, Nigel made it out of the murder house too—he’d only started screaming because I was holding the flashlight, and I’d just run off and left him in the dark.

We didn’t speak much after that.

Top image from the first season of American Horror Story.

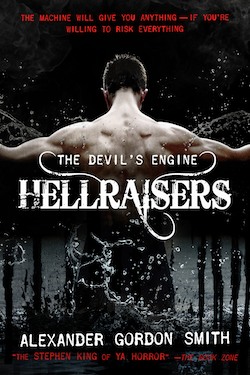

Alexander Gordon Smith lives in Norwich, England. He is the author of the Escape from Furnace and Hellraisers series.