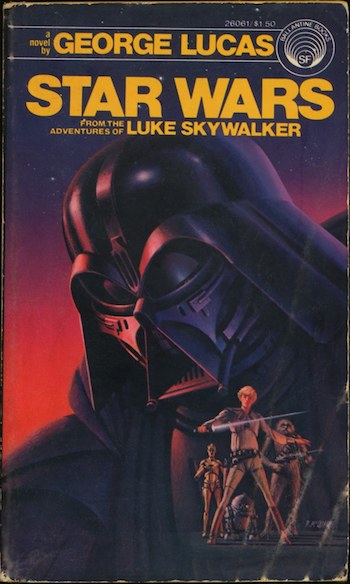

At this point, it’s pretty well known that the novelization of Star Wars: A New Hope was not written by George Lucas himself, but ghostwritten by Alan Dean Foster. George Lucas admitted in a foreword written during the mid-90s that he hoped the book would be a modest success, just the way he hoped the film would be. The book sold just fine… and then the movie came out, and the book started flying off shelves.

The book is an odd piece of work for many reasons. Foster was clearly given background from Lucas’ notes that never made it onto to the screen, but he also gives the story very specific world-building, the sort that you normally wouldn’t get from a film novelization. It might be a little too specific. In fact, the novel doesn’t feel much like Star Wars at all; most of the same actions take place (and a few extra from cut scenes and the like), but the descriptions, the motivations, the overall arc of the story feels more like a traditional fantasy novel with a lot of tech speak thrown in. This makes sense when we see the sort of sequel that Foster created in the event that Star Wars didn’t do as well commercially, but it’s plain odd to read these days.

Lucas pointed out that the novel’s prologue contains an outline for the universe that’s quite similar to the one we see in the Star Wars prequels, proving that he had the vague shape of the Republic’s fall in mind when he put the original trilogy together. Ryan Britt wrote an article on this very site concerning the differences between this book and the film, which pointed out the ways in which that prologue diverges from the story the prequels gives us–the primary one being that Palpatine isn’t technically supposed to be in charge. A fake historical text excerpt informs us that he’s being controlled by the people who were once his assistants and yes-men. The prologue then gives us this quote before it launches into the action:

“They were in the wrong place at the wrong time. Naturally they became heroes.”

Leia Organa of Alderaan, Senator

It’s odd because it seems to indicate that Leia’s talking about Luke and Han to the exclusion of herself. As though she wasn’t a hero in this story as well. Sure, they have to bail her out of the prison, but she’s the one who gets the Death Star plans safely into a small crafty droid. She also holds up under torture. Oh, and watches her whole planet get destroyed, and still refuses to give up the Rebels. I dunno. I guess this snippet could be from an interview where the reporter just keeps nagging Leia about her compatriots. But it seems likely instead that the Foster considered Leia to be more of a diplomat and politician than these films eventually make her out to be.

One thing that always catches my attention here is probably weird to point out, but I’ll do it anyway: this book spells the droids’ names out as Artoo Detoo and See Threepio. Using the phonetic spelling for our beloved duo’s names is a tradition in Star Wars books, and it’s fascinating to me that it’s a tradition that started with the very first tome… which was released before the film came out.

Perhaps the book’s greatest success is in giving a clearer picture of life on Tatooine, making the planet seem far more hostile and unforgiving. We find that Uncle Owen trades the bad R2 unit the Jawas sell them for Artoo–rather than causing a scene–because there’s every chance that the Jawas might roll their sandcrawler right over his home, leading to an outbreak in hostilities between the human and non-human population of the planet. (The book also says that some scientists believe Jawas to be mature versions of the Sandpeople, though, which is outright laughable. They shrink as they get older?) We also get all the information from the film’s deleted scenes with Luke and his friends, including that first scene with Biggs Darklighter, and his admission that he’s leaving the Academy to join the Rebels.

Luke’s character is more fleshed out in this book, and he is every inch a teenager. His interest in anything that would take him far from home, his need to do something useful with his life is what drives the story forward, as it should. He’s also more obviously from the sticks; there’s nothing quite so amusing as his exclamation when Obi-Wan tells him to come with him to Alderaan: “Alderaan! I’m not going to Alderaan. I don’t even know where Alderaan is.” Aw, Luke. It’s okay. You’ll get a few galactic maps and be up on this stuff in no time.

Obi-Wan is hilariously irascible, even more so when he’s given more to say. His explanations of the Force (strangely not a capitalized word in this book) are weirdly vague and unhelpful. Han is introduced with a “humanoid wench” in his lap at the Mos Eisley Cantina. So that’s a thing. The Jabba deleted scene makes it in as well, but this time Hut (with one ‘t’) is described as a “great mobile tub of muscle and suet.”

Oh! And while every good Star Wars fan knows the reason why Han says the Falcon has made the Kessel Run in less than twelve parsecs when a parsec is a measure of distance, in the book, he claims the Falcon made the Run in “less than twelve standard timeparts.” Wonders never cease. The banter between Han and Luke is decidedly improved once we hit the Death Star, Ben wanders off, and the farm boy tries to convince his new pal to go rescue a princess with him:

“Where’s your sense of chivalry, Han?”

Solo considered. “Near as I can recall, I traded it for a ten-carat chrysopaz and three bottle of good brandy about five years ago on Commenor.”

“I’ve seen her,” Luke persisted desperately. “She’s beautiful.”

“So’s life.”

On the other hand, we’ve got maximum awkwardness from Foster clearly believing that Luke and Leia were meant for each other. Luke’s crush is given far too much attention, making everything an extra layer of gross. It’s like Star Wars in an alternate universe, where different aspects of the story were meant to come true. On the positive end, Foster actually bothers to detail how little consideration droids are given by humans, with Luke marveling at how much personality Threepio has, and feeling surprised at how attached he’s growing to the droid. He also notes how reverently Artoo is handled by Rebels technicians when they take him away to unearth the Death Star plans, the first time he has ever witnessed a robot being handled with such care by men. In that way the book manages to touch on one of the more uncomfortable aspects of the universe that’s never well-addressed.

There’s a jarring moment before the Battle of Yavin where one of the Rebel pilots tells Luke that he knew his father… which I sort of wish was in the actual film, seeing as very few people know the true identity of Vader. It’s entirely possible that some of the older Rebel fighters were around during the Clone Wars, and encountered Anakin as some point. The battle sequence draws out the road to Biggs’ demise so that it hurts far worse than you’d expect (his final words in the hangar are actually given to Luke following his death–“We’re a couple of shooting stars, Biggs, and we’ll never be stopped”), and Luke’s use of the Force is made far clearer in the narrative; he fires that final torpedo in a daze, and barely remembers doing it at all.

It’s an interesting companion, but it simply doesn’t do what the film does. And that’s the way it should be–something that works so well on film doesn’t have to be a good book. It’s an interesting exercise for completists, and more interesting still for the fact that some fans read this book before they ever saw the film. But it’s not “essential” Star Wars in any sense… more a strange window in time.

Emmet Asher-Perrin really never needed to have Jabba described that way to her. You can bug her on Twitter and Tumblr, and read more of her work here and elsewhere.