Today’s bestsellers are tomorrow’s remainders and Forgotten Bestsellers will run for the next six weeks as a reminder that we were once all in a lather over books that people barely even remember anymore. Have we forgotten great works of literature? Or were these books never more than literary mayflies in the first place? What better time of year than the holiday season for us to remember that all flesh is dust and everything must die?

Everyone thinks they’ve read a Robin Cook novel.

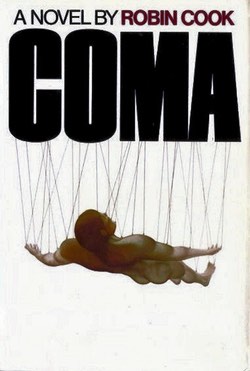

Brain, Fever, Outbreak, Mutation, Toxin, Shock, Seizure…an endless string of terse nouns splashed across paperback covers in airports everywhere. But just when you think you’ve got Robin Cook pegged, he throws a curveball by adding an adjective to his titles: Fatal Cure, Acceptable Risk, Mortal Fear, Harmful Intent. Cook is an ophthalmologist and an author, a man who has checked eyes and written bestsellers with equal frequency, but the one book to rule them all is Coma, his first big hit, written in 1977, which spawned a hit movie directed by Michael Crichton. With 34 books under his belt he is as inescapable as your annual eye appointment, but is he any good?

Consider Coma.

It wasn’t actually Cook’s first book. Five years previously he’d written The Year of the Intern, a sincere, heartfelt novel about life as a medical resident, which no one cared about. Stung by its failure he vowed to write a bestseller, so he sat down with a bunch of blockbuster books (Jaws for one) and tried to figure out their formula. I hardly need to point out that this is exactly what you would expect a doctor to do. And if Coma is anything, it’s formulaic.

The engine that drives this bus is Cook’s realization that organ transplant technology was well on its way to being perfected, but the problem with the procedure was a supply-side one: there simply weren’t enough raw materials. Couple that with the fact that, “I decided early on that one of my recurrent themes would be to decry the intrusion of business in medicine,” and the only thing surprising about the plot of Coma is that no one had come up with it before.

Susan Wheeler is one of those beautiful, brilliant, driven medical students who is constantly either inspiring double takes in her male colleagues or looking in the mirror and wondering if she’s a doctor or a woman, and why can’t she be both, dammit. In other words, she’s a creature of 70’s bestselling fiction. On her first day as a trainee at Boston Memorial she decides that she’s a woman, dammit, and she allows herself to flirt with an attractive patient on his way into surgery for a routine procedure. They make a date for coffee, but something goes wrong with the anesthesia and he goes into…a COMA.

Determined not to be stood up for coffee, Susan researches what happened to her date and discovers Boston Memorial’s dirty secret: their rates for patients lapsing into coma during surgery are above the norm. Susan believes that she might be on the trail of a new syndrome but her teachers and supervisors tell her to drop this mad crusade. Instead, she uses com-pew-tors to analyze her data and the shadowy figures running this conspiracy decide that enough is enough. If com-pew-tors are getting involved then Susan Wheeler must be stopped! So they hire a hitman to attack Susan, then change their minds and decide to send him back to murder her also too and as well. In the meantime, Susan’s falling in love with Mark Bellows, the attractive and arrogant surgery resident who is her supervisor.

Cook wasn’t kidding when he said that he had figured out the formula. There’s a chase, a narrow escape, a betrayal by a trusted authority figure, and a final scene with a striking standout image which you’ve seen on the posters for the movie: a massive room with comatose patients suspended from wires stretching out into the distance. Formula isn’t always bad, however, and Cook makes sure that the climax of his book happens in the last 20 pages, about three pages from the end he puts Susan in mortal peril that seems inescapable, then he brings in a previous plot point, now forgotten, that turns out to be the hinge that leads to her dramatic rescue as the police arrive, the bad guy is arrested, and quite literally before the bad guy even gets a chance for a final dramatic monologue, the book is over.

Coma is nothing if it’s not efficient, and the whole “Big business is stealing organs from comatose patients to sell to rich Arabs” conspiracy is realistically thought out. He originally wrote the novel as a screenplay, a format whose influence can still be seen in the fact that the novel begins each chapter with a scene description rather than dialogue or action, which gives it a brisk, businesslike tone and keeps too much personal style from intruding. Cook has also figured out that other part of the bestseller formula: readers like to learn things. Read a John Grisham and you’ll learn about the legal system, read a Tom Clancy and you’ll learn (way too much) about military hardware, read a Clive Cussler and you’ll learn about deep sea diving, and read a Robin Cook and you’ll learn about medicine. A lot about medicine. A whole lot about medicine.

In the section of his Wikipedia page marked “Private Life” it reads, “Cook’s medical thrillers are designed, in part, to keep the public aware of both the technological possibilities of modern medicine and the ensuing socio-ethical problems which come along with it.” Cook hammers this home in interview after interview: he wants to educate people. This is an admirable goal but it means that his books feature dry lectures on every aspect of medicine, and in Coma this tendency is already evident. Cook views his books as teaching tools and that causes them to lapse into the plodding rhythms of a lecturer unaccustomed to interruption. It’s a failing he shares with Michael Crichton, another MD-turned-author.

Coma spent 13 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list when it came out, mostly lingering around position 13 or 14, occasionally rising as high as position eight. It was made into a movie, and launched Cook’s brand, and the rest has been a long string of books with plots that sound suspiciously like Coma:

- “Lynn Pierce, a fourth-year medical student at South Carolina’s Mason-Dixon University, thinks she has her life figured out. But when her otherwise healthy boyfriend, Carl, enters the hospital for routine surgery, her neatly ordered life is thrown into total chaos.” (Host, 2015)

- “Dr. Laurie Montgomery and Dr. Jack Stapleton confront a ballooning series of puzzling hospital deaths of young, healthy people who have just undergone successful routine surgery.” (Marker, 2005)

- “A medical student and a nurse investigate medulloblastoma cases. By the time they uncover the truth about seemingly ground-breaking cures, the pair run afoul of the law, their medical colleagues, and the powerful, enigmatic director of the Forbes Center.” (Terminal, 1995)

- “A gigantic drug firm has offered an aspiring young doctor a lucrative job that will help support his pregnant wife. It could make their dreams come true—or their nightmares…” (Mindbend, 1985)

- “Charles Martel is a brilliant cancer researcher who discovers that his own daughter is the victim of leukemia. The cause: a chemical plant conspiracy that not only promises to kill her, but will destroy him as a doctor and a man if he tries to fight it…” (Fever, 1982)

There’s nothing wrong with this formula, and Coma is probably the book in which it feels freshest. But it’s interesting to note that Cook only turned to his formula after his first, non-formulaic novel was rejected by the reading public, and it’s even more interesting that the success of Coma didn’t make him want to repeat it right away. His follow-up novel? Sphinx, about Erica Baron, a young Egyptologist investigating the mysteries of an ancient Egyptian statue in Cairo. It wasn’t a hit. His next book? Well, you don’t have to teach Robin Cook the same lesson thrice. It was Brain, in which, “Two doctors place their lives in jeopardy to find out why a young woman died on the operating table—and had her brain secretly removed.”

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today and his latest novel is Horrorstör, about a haunted Ikea.