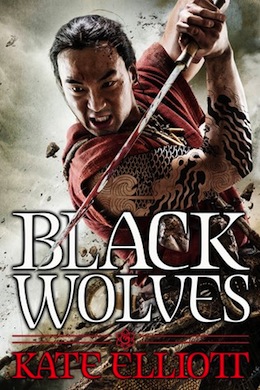

I’m not sure that any review I write can do adequate justice to Kate Elliott’s Black Wolves. Here are the basic facts: it’s the first book in a new series. It’s set in the same continuity as her “Crossroads” trilogy (begun in 2007 with Spirit Gate), but several decades on, and with an entirely new cast of characters. It’s out today from Orbit. And it’s the work of a writer who’s reached a new peak in skill and talent, and has things to say.

On one level, this is good old-fashioned epic fantasy. A kingdom in turmoil; young men and young women in over their heads, secrets and lies and history, power struggles and magic and people who ride giant eagles. It has cool shit.

On another level, this is a deconstruction of epic fantasy. An interrogation of epic fantasy: it turns the staple tropes of the genre upside down and shakes them to see what falls out. It reconfigures the landscape of epic fantasy, because its emotional focus is not—despite initial impressions—on kingship and legitimacy, inheritance and royal restoration. So much of the epic fantasy field accepts the a priori legitimacy of monarchy—or the a priori legitimacy of power maintained through force—invests it with a kind of superstitious awe, that to find an epic fantasy novel willing to intelligently interrogate categories of power is a thing of joy.

Because Kate Elliott is very interested in power, in Black Wolves. Kinds of power, and kinds of violence. Who has it, who uses it, who suffers from it, who pays the price for it—and how. Each of her five viewpoint characters are a lens through which we see power and violence play out from different perspectives: Kellas, a warrior and spy whom we first meet as a man of thirty, with his loyalty to his king just about to be challenged, and whom we see again later as a septuagenarian with a mission; Dannarah, the daughter of a king, whom we see first as a stubborn adolescent and meet later as a marshal among the giant-eagle-riders who serve the king’s laws, a leader in her sixties with a complicated relationship to her royal nephew and greatnephews; Gil, a young nobleman from a disgraced family who must marry for money; Sarai, the young woman whose mother’s disgrace means her family is willing to marry her to Gil; and Lifka, a young woman whose poor family adopted her as a child from among the captives brought back from war, and who comes into Dannarah’s orbit when her father becomes the victim of royal injustice.

Elliott examines the role of violence, actual or implied, in the operation of power; and the role of power in the use of violence. Black Wolves is a book that looks at state violence, in the exaction of tax and tribute and the creation of an order that upholds the powerful; political violence, in the conflict between the king’s wives over which of his children will inherit his throne; and the violence of cultural erasure, as the laws and customs of the Hundred are remade to better suit the desires of the king and his court and their foreign supporters. (Black Wolves is, too, a novel that’s deeply interested in the effects and after-effects of colonisation.)

For all this interest in violence, however, it is significant—and in some ways radical—that when we see sexual violence on the screen, it is as a tool of punishment deployed by men against other men, and not against women. There is a near-complete absence of sexual violence and constraint directed against women. Indeed, Sarai’s storyline includes consensual and mutually enjoyable relationships both with her former lover, the woman Elit, and with her present husband, Gil—though both of these are complicated by war, separation, and conflicting obligations. (I will confess to rooting for an eventual ending that lets them have a happy triad, if Elliott lets them all stay alive to the ultimate conclusion.) The women in Black Wolves are shown as not just having agency and influence, but having sexual agency—which the narrative doesn’t diminish or punish. That’s a choice that’s still fairly uncommon in epic fantasy, and one that delights me.

Speaking of women! The women in Black Wolves, as well as having sexual agency, are shown as the primary political movers, even if living in seclusion like the king’s first wife. Especially the older women. It is their choices that lead to major change—and major upheaval. And among the viewpoint characters, while Gil and Kellas are working to agendas outlined by others, Dannarah, Sarai, and Lifka are significant independent movers of change.

This is a novel about politics. It’s politics all the way down. It’s about families of blood and families of choice, families of chance and family secrets and betrayals. It’s about heritage and inheritance in all senses. It’s also an argument about law, justice, and what happens on the edges of empire. It’s about consequences.

All about consequences.

Also, it has giant fucking eagles.

I think it’s brilliant. If it has one serious flaw, it’s that it takes about a hundred pages (out of seven-hundred-odd) to really find its stride: the first hundred pages are set forty years before the next six hundred. Eventually, it becomes clear why Elliott made this choice, and how it works in looking back to the “Crossroads” trilogy and forward to what she’s doing here: but it takes a little time before the reader’s patience is rewarded.

But damn is patience rewarded. This is a really excellent epic, and I’m on tenterhooks to see what happens next.

Unfortunately, there’s another year to wait…

Black Wolves is available now from Orbit.

Liz Bourke is a cranky person who reads books. She has recently completed a doctoral dissertation in Classics at Trinity College, Dublin. Find her at her blog. Or her Twitter.