For the fairest. Past, present, and future. Again.

For Sonya Taaffe

The goddesses came to him three, when he was already thinking about numbers. One had her hair high-crowned with peacock’s feathers woven together, and her mouth sardonic. One had hair the color of a yellow sun above the noontide sea, foam-fine, her eyes sideways smiling. And the last was tapping a war beat upon the helmet under her arm, one-two, one-two-three, one-two.

He didn’t see them at first, lost in sandglass musings, and polygons begetting polygons, and infinite sums. In one-to-one correspondences and sheep counted by knots upon cords. An abacus, resting on his knee, dreamed of binary numbers and quantum superpositions; harmless enough, in this slant of time. It wasn’t so much that Paris was a mathematician. Rather, it was that Ilion was a creation of curvatures and angles and differential seductions, and he was the city’s lover.

Then the first visitor said, quietly but not gently, “Paris,” and he looked up.

Paris set his stylus aside, trailing smudged thumbprints and a candle-scatter of photons. “I must remember to get drunk more often,” he said quizzically, “if the results are always this agreeable.”

The first goddess gave him a smile like leaves curling under frost. “What a pity for you,” Hera said. “You’d like this much better if it were about pressing wine from your fancies.”

“Where are my manners?” he said, although he had already figured out that if having one god in your life was iffy luck, three was worse. “I doubt anything I could offer would be worthy of your palates, but maybe the novelty of mortal refreshments would suffice? I still have liquor of boustrophedon laments around here somewhere.”

“Oh, what’s the harm,” Aphrodite said. Her voice was sweet as ashes, and Paris kept his face carefully polite despite the heat stirring in him. Futile, of course, especially the way she was looking at him with that knowing quirk of the lips. “A glass?”

“No, I want this done,” Hera said. “Indulge yourself later, if you want.”

Athena spoke for the first time. “I have to agree,” she said gravely.

“Then—?” Paris said. “You can’t be here because you’re looking for my charming company. At least, I can’t imagine that charming company is difficult for you to find.”

“Hasn’t your father ever warned you about being glib?” Hera said.

He only smiled, on the grounds that opening his mouth would just irritate her. Hera was high on his list of people not to irritate.

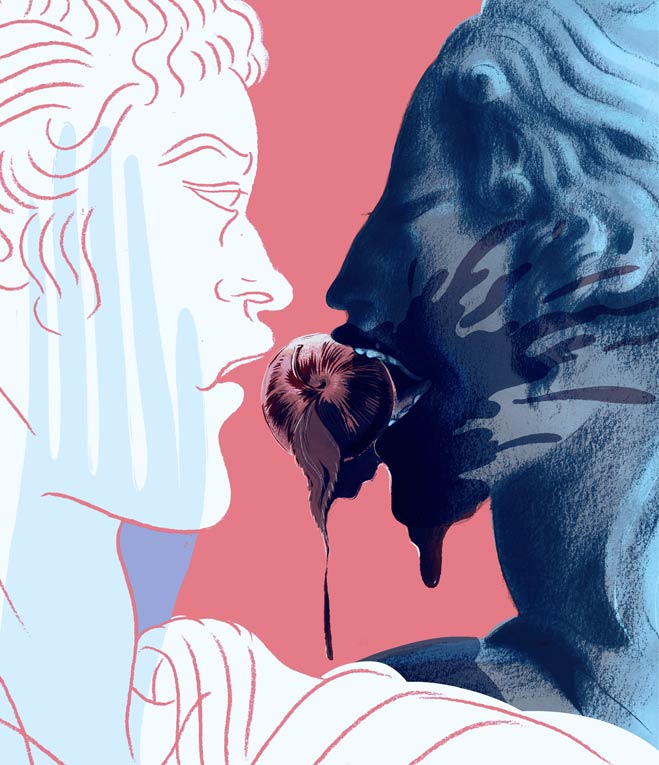

It was then that Hera produced the apple. Its brightness was such that everything around it looked dimmer, duller, drained of succulence. “What a prize,” she said softly, bitterly. “No one wants the damn thing, except being uncrowned by its light is even worse. Someone has to claim it.”

“Choose by random number generator?” Paris said, because someone had to.

“As if anything is truly random in the stories we write for ourselves,” Athena said. Because of the apple, even her voice was gray, not the clear gray of a sky forever breaking dawnward, but the gray of bitter smoke.

Uninvited, Aphrodite took up the abacus, sank down onto Paris’s bed, and stretched out a leg. Her ankle was narcissus-white, neat, the arch of her foot as perfect as poems scribbled into sand and given to the tides. She shook the abacus like a sistrum. The rhythms were both profane and profound, and he could not escape them; his heartbeat wound in and around the beats. Then she put it down and he could think again. Her sideways eyes did not change the whole time.

“Why me?” Paris asked, the next obvious question. Or maybe the first one, who knew.

“Because there’s a siege through the threads of time,” Athena said, “and you are knotted into it. Not that you’re the only one, but that’s not yours to know, not yet.”

Paris looked yearningly at the abacus, but it had no answer for him. “I am under no illusions that Ilion will stand forever,” he said. “Still, I had hoped it would last a little longer.”

“If that’s your wish,” Hera said, “choose accordingly.”

“Indeed,” Athena murmured.

Aphrodite said nothing, only continued to smile with her sideways eyes, and Paris went hot and cold, fearing that the puzzle had no solution.

A few words need to be said about the apple at this point.

It had no fragrance of fruit, or even flowers, or worm-rot. It smelled of diesel hearts and drudgery and overcrowded colonies; of battery acid gone bad and bromides and foundered courtships. Intoxicating, yes, but in the way of verses etched unwanted upon the spirit’s cracked windows. The smell was so pervasive that, once the apple showed up in the room, it was hard to imagine life without it. Not inaccurate, really.

The apple was not precisely the color of gold. Rather, it looked like bottle glass worn smoothly clouded, and if you examined it closely you could see the honey-haze of insincere endearments inside-out and upside-down and anamorphically distorted shining on the wrong side of the skin, waiting for you to bite in and drink them in, juice of disasters dribbling down your chin. Paris didn’t have to take the bite to know how the apple tasted.

Paris could have awarded the apple to Hera. (For the fairest, it proclaimed, as though partial ordering was possible.) A lifetime’s empire, and the riches to go with it. A prince, he was no stranger to the latter, even if (especially in time of war) there was no such thing as too much wealth. But he knew that it was one thing to scythe down the world with your shadow, and another to build ships, schools, roads; to gird your conquests with the integument of infrastructure. Even if the queen of the gods felled nations for him, conquest was never the hard part. As his mother often said, a hundred dynasties guttered out every day, from fire or famine or financial collapse.

He could have done the obvious and given it to Aphrodite, either because he ached for some phantasm of heart’s yearning, or because he wanted to warm himself with a moment’s kindling of appreciation in those sea-shadowed eyes. But that’s an older story by far than this one.

That left Athena, gray-eyed, giver of wisdom. Athena, who leaned down to whisper in his ear that there were mysteries even greater than the ones he jousted with. Books of sand; tessellations of dart and kite, never-repeating; superpositions of sines in a siren’s song ever-descending.

And here was where Paris did something even the farsighted warrior goddess didn’t predict. He refused her too.

After the goddesses left, the room was full of shadows athwart each other, and mosaics unraveling into fissures, and sculptures scavenged from ruined starships. Paris saw none of them. Instead, he only had eyes for the apple. They had left it with him; they knew his decision, and they had no reason to believe that he would renege on it.

The apple did not burn his hands. It did, however, leave a prickling residue, which he could not see but which clung to his skin. He hoped the effect was temporary.

Ilion, nine-walled Ilion, spindled Ilion with its robed defenses. Outside and inside, the city-fort shone black, girded with lights of pearling white and whirling gold. He walked through its halls now, listening to the way his footsteps were swallowed by expanses of silence, toward its heart of honeyed metal and striated crystal. As he traversed the involute path toward Ilion’s center, the apple whispered to him of radioactive decay and recursive deaths, of treaties bitcrushed into false promises.

No one said this was going to be easy, Paris told himself ironically, and avoided looking at his blurred reflection in the sheening walls, the way his shadow stretched out before him as though yearning toward the dissolution past a singularity’s boundary.

At last he came to Ilion’s heart. The doors were open to him; they always were. He paused, adjusting to the velvet air, the sweetness of the warm light.

“Paris,” Ilion said. He sat with his feet crossed at the ankles, on a staircase that led down to nowhere but a terminus of gravitational escapades. Today he was a dark youth, clear-eyed, with curls that always fell just so. Two days ago he had been a tawny girl with long lashes and small, neat hands, the fingernails trimmed slightly too long for comfort. (Paris had the scratches down his back to prove it.)

Paris hesitated. The usual embrace would be awkward with the apple in hand, and setting the thing down struck him as unsafe, as though it would tumble between the chinks of atoms and disperse into a particle-cloud of impossibilities. “I have a gift for you,” he said, except his throat closed on gift.

“An ungift, you mean,” Ilion said. His voice was light, teasing, accented precisely the way that Paris’s was.

“Don’t,” Paris said. “Don’t make this a joke.”

“I wasn’t going to,” Ilion said, but the crookedness of his mouth suggested otherwise. Unhurriedly, he rose and ascended step by step, barefoot, crossing to clasp Paris’s upper arms. “So tell me, what possessed you to bring this particular treasure here, instead of letting someone else have nightmares over it?”

No one had ever accused Ilion of having a small ego. Paris supposed that if he were as old, with an accompanying habit of kaleidoscope beauty, he’d be conceited, too. More conceited than he currently was, anyway. “Because it’s for the fairest,” Paris said. He met Ilion’s eyes. “And, frankly, because if anyone has a chance of keeping the wretched thing contained, it’s the oldest and greatest of fortresses.”

“Flatterer,” Ilion said, smiling. “Do you never listen to your brother when he goes on about strategy? Only an idiot picks a fight when they could avoid it instead.”

“You are walls upon walls,” Paris said. “It’s you or no one.”

“Give it here,” Ilion said after a moment’s pause.

Paris didn’t want to let go of the apple, despite its whispers. He felt it clinging to his skin. Clenching his jaw, he dropped it into Ilion’s outstretched hand.

For a moment, nothing. Then the city was lit by the apple’s light, as though it was a lantern of condensed evenings. Everything was painted over with the jitter-tint of unease, from the factories where cyborgs labored with their insect arms to the academies with their contests of wit and strength, from the flower-engraved gun mounts to the gardens where fruits breathed of kindly intoxications.

“It’s not without its charm,” said Ilion, who had odd ideas about aesthetics. “Have you talked to your parents?”

“I didn’t exactly have the time for lengthy consultations,” Paris said. “And besides, all their protestations don’t mean anything if you’re not agreeable.”

“Too bad you’re too old to be flagellated,” Ilion said, but he was smirking, and for a moment a silhouette-flicker of scourges twined around his ankles.

Paris resisted the urge to roll his eyes.

Ilion cocked his head. “I can hear the war fleets drumming their way through the black reaches even now,” he said. “Will you love me when all that’s left is a helter-skelter of molten girdings and lightless alloys? And the occasional effervescing vapor of toxic gas?”

“At that point I’ll be dead too,” Paris said, unsympathetic.

“It’s a bit late to get you to think this through,” Ilion said dryly. “Well, I suppose it was high time we enjoyed a challenge.”

With that, he tossed the apple up in the air, high, high, until it was a glimmer-mote of malicious amber. Paris’s heart nearly stopped. Then it plummeted to land with a smack in Ilion’s hand. He brought it up to his mouth and bit into it. Paris almost gagged at the sudden sweetness of the apple’s stench, the overwhelming pall of juice that evaporated as soon as it was released from the apple’s pale flesh.

“You’re crazy,” Paris said.

“No crazier than you are,” Ilion retorted. “I’m merely reifying the situation.”

Ilion ate the entire apple, core and all, or perhaps, more likely, it had never had any core except a mist of recriminations. Paris was willing to bet that its seeds were everywhere, and always had been.

“Come here,” Ilion said, barely loud enough for Paris to hear him over the taut silence. His lips curved, asymmetrical; his eyes were shadowlit with desire.

Paris was not known for moderation or good sense, but he said, “I don’t think this is the time—”

Ilion grasped his shoulders and dragged him closer. He was sometimes taller and sometimes shorter. Right now Paris couldn’t tell, drunk as he was on the apple perfume on Ilion’s breath. The kiss lasted a long time. I am never going to surface, he thought at one point, before giving himself over to the taste of candied massacres.

“There,” Ilion said, releasing Paris so suddenly he stumbled backwards and only just caught himself against a column crowned with translucent leaves. “I wanted to give you an appetizer of what we’re about to go through.” There was the merest undercurrent of pity in his voice. “You could have made a pretty face the focus of all the troubles coming for us, I suppose, but the end result is the same.”

“I have no idea what you’re talking about,” Paris said, lying. Shades stood around the two of them, a veil of suffocating possibilities. “I must take my leave of you. My parents are not going to be in a forgiving mood.”

“Since when have you ever cared about their opinion?”

“I’m sure they’re going to be asking themselves the same thing,” Paris said, and left.

Paris didn’t make it to the hall of halls before his sister intercepted him.

The passages of metal brightened with pattern-mazes of snaking circuitry, pulsing in on-off foreboding. “Paris,” Cassandra said in encrypted flashes. The effect was not unlike taking a scalpel through the retina. “Tell them the truth.”

There was no point in hiding anything from her if she knew this much already. “I’m going to,” Paris said, a little wearily. The unfortunate problem with Cassandra’s binary existence was that, for all the things she saw, her version of reality never seemed entirely compatible with the one that everyone else experienced.

“Tell them it’s about a woman,” Cassandra said. “She’ll be the death of us, Paris.”

“I’m not going to endanger us for some new lover,” Paris said with the patience of long practice. “I have Ilion. Unless Ilion is the woman you mean.”

“Not Ilion,” Cassandra said. “The one who has your heart.”

He reached out and pressed his hand against the wall. The light had no heat, although he fancied the warmth of kinship passed between them anyway. “Sister-sweet,” he said, “there’s love and there’s love, and I would never betray us that way. I glimpsed what Aphrodite offered, and she was beautiful the way a stellar furnace is beautiful, but please think better of me than that.”

Cassandra said nothing.

“Cassandra.”

“Well,” she said, “I suppose it is not as if she, too, didn’t have her choices.”

“I have no idea what you mean by that. Please, Cassandra.”

The lights unsnaked, and he was left alone in the hall. Telling the rest of his family came easily, compared to that. Dutifully, he reported Cassandra’s misgivings as well, but no one else knew what she was getting at, either.

They saw the ships coming from a long way off.

Every evening Paris looked through Ilion’s unoccluded eyes at the fleets setting out for the fortress. “I am the fruit of fruits now,” Ilion had said the other day, their lips smiling, “and they’ve come to pluck me.”

Paris had been lying in Ilion’s arms. “You sound so pleased,” he muttered.

“Shouldn’t I be?” Ilion said reasonably. “I have my pride too. Let them shatter themselves against my walls. Or, more prosaically, against high-velocity kinetic projectiles.”

“Hector likes to say you can’t win a war on the defensive.”

“Hector is as loyal to me in his way as you are in yours,” Ilion said, pleased as a cat. “He’ll be happy to fight when I require it.”

“He’s more ship than human, these days. I hear him singing when he’s out there. The hot sweep of flight. One of these days he won’t come back.”

Ilion prodded him uncomfortably close to his groin. “Now you’re being unfair,” they said. “He comes home each time, punctually as you please.”

“Fine,” Paris said. “Fine.” There was nothing to argue: Hector did, in fact, come back punctually every time.

Time passed like vapor, or foam, or yearning dust. And the ships: during that time the ships gathered in great fleets. Some of them were the same color as the night, silhouettes as predatory as silence. Some of them were gaudy-bright, phoenix-bronzed. Some burned as they flew. Ships that had once been moons, digested and regurgitated into their present form by choral nanites. Ships that named each gun after a different genocide. Ships crewed by the dead, their expertise distilled into decision trees of astonishing agility.

All of them were coming for Ilion.

Discord. War of wars.

A few ways the war transpired:

In one version of the story, Ilion took on the garments of nine-tailed fox spirits, robing itself in their keen eyes and their curling riddles. Vast armies, with sun chariots and fire arrows and star spears, rode across forever shores of smoke and scratchless glass, never reaching their goal; rode in random walks across maps that changed each time they took a reckoning. Their generals conferred among themselves. Chief among them was a woman old in battle but young in the ways of cities. Her counsel, to the others’ dismay, was to withdraw instead of wandering across the mire of their own impatience. After many days of argument they finally agreed. All that time Ilion whispered into her visions, wearing the face of her own ambitions.

In the meantime, Ilion of the many shapes, Ilion of the nine-veiled walls, was overtaken by a procession of numerate factions. Every plant in the spinward gardens hung with fruit whose flesh had the texture of cooked eyes. The Nines went about in fox-masks, and a civil war ensued between those who poured libations to prime numbers upon silicate altars and those who poured libations to composite numbers. Paris parted ways with his family in the early days, withdrawing behind the fortress’s occlusions to design improved defenses. He studied Zhuge Liang and Vauban and Mardi bin Ali al-Tarsusi, he steeped his dreams in the properties of degenerate matter, and for all his care he was caught half-drowsing in Ilion’s arms when at last bird-cloaked insurgents caused the fortress to fold in on itself like crushed paper.

The generals waited, and waited, and waited, and at last their chief sacrificed her face to the sky and sea and liminal shore. Concealed by a helmet from which three eyes stared lidlessly, she went before her lieutenants and told them the time had come to sack the city-fortress. Even now Ilion’s fame had not waned. Songs of its treasures, of its metal heart and petal beauty, were still chanted in the sky courts and hell chasms and the surfeit of night roads.

By the time they arrived, they were much diminished in number, but great in glory. Ilion itself welcomed its new rulers. “We are the same,” it said to the chief, and smiled at her with her own face. She realized then how she had been tricked, but it was too late. Her generals were only too content to become part of the prize they had sought so long.

This victory was not without its price. Ilion’s people took up the obeisances and rituals of their new masters, and even the numerate factions fell into disarray.

In another version of the war, Ilion descended upon an immense artificial world of ocean, concealing itself in its depths like a belated pearl-irritant. Braids of kelp became her hair, and during the festivals of war preparation, she decorated herself with the whorled dances of transparent eels and algal blooms.

Fleets upon fleets came to orbit the world of ocean, intending to boil away the waters layer by layer. Instead, they were subsumed by the sea reverie. Spherical dreadnoughts condensed into whale shapes. Flights of missiles became voracious finned schools, themselves consumed by carriers that sprouted anemone banners. It was not long before the invaders had joined Ilion’s ecology of untided longings.

Ilion’s children learned the undulant languages, applied themselves to the study of fluid dynamics, and wrote disparaging treatises that, misconstrued in realities slightly aslant their own, birthed legends of sunken civilizations.

In yet another, Ilion, like a great maw, began digesting the beings sentient and non-sentient who dwelt within it. As it did so, it encrusted itself with minerals and mirrors, an armor of prolix crystallography. The voices of its victims thundered through the space-time membrane, threnody absolute. Every guidestar that knew Ilion’s name was unmoored from the firmament and crushed into singularity specks. Of Ilion itself, nothing remained but a vast jeweled simulacrum of apple-plague.

We could go on in this manner, but these examples suffice to demonstrate Ilion’s inability to escape the apple’s nature.

It was the tenth year of the siege (the hundredth, the billionth). Paris leaned back in Ilion’s arms and listened to the shield beat and the spear chant, the unsound of missiles and catapulted projectiles hurtling through the black depths. “I can’t imagine what it would be like to sleep in a time of peace anymore,” he remarked.

“Don’t be ridiculous,” Ilion said. “You’re adaptable.” He shifted his leg, and the gown he wore slipped sideways to reveal a tanned expanse of thigh. Ilion’s clothing was a matter of opinion. Every time Paris thought he had eased all of it off, he found another coy fold of tunic, or tassels covering an ankle. There was no such thing as a completely naked city. You could dig and you could dig, you could walk the walls under the night’s unkind eyes; nevertheless, farther down you’d always find some furrowed bone, some scratched potsherd, some hexadecimal couplet stamped on plastic.

“Do you ever wonder what they’re up to, out there?” Paris said.

“You mean besides throwing glorified space rocks at us?”

Paris snorted. “They must live and love and die, the same as we do,” he said, moved by an unaccustomed swell of sentimentality. “They must have children of circuitry or flesh or cunning brass. And some of them must be as sick of this whole conflict as we are.”

Ilion tapped impatiently on the couch. The walls shivered black, then red-gold-pale with the burstlights of the bombardment, the light of local stars glinting off the barding of massed ships. “Yes,” Ilion said, “they’re so sick of it that they’re going home.”

“They must want something concrete out of all this.”

“Glory,” Ilion said. “Vengeance, spite, security, the sheer unadulterated expression of aggression. None of these, I will note, is concrete.”

“You could vomit up that damn apple. I wish—” Paris bit his tongue.

Ilion refrained from an entirely redundant I told you so. This was, at least, an improvement over the first nine years.

“I am going to fall asleep here,” Paris said. “And I’m going to dream of enjoying silence, and waters unblemished by ships, and eating nothing to do with fruit—no sauces, no preserves, no fresh chilled slices, nothing—for the rest of my life.”

Ilion threaded his fingers through Paris’s hair, untangling a lock. It almost didn’t hurt. “Sleep, then,” he said in a voice sweet as water. “It won’t be much longer.”

Paris meant to ask what he meant by that, but his eyelids drooped, and sleep descended upon him. Whether he had the dreams he had wished for, he never remembered.

Late in the last year, some but not all of the enemy fleets withdrew. Hector and the defense fleets were on high alert for weeks afterward, patrolling Ilium behind the cover of its flanged force-screens. Paris edited out his need for sleep, as much as he longed for the escape, and oversaw the city’s artillery defenses. Far-archer, Ilion’s guns said of him, mostly with affection, where he could hear them. (They called him other things behind his back, in the way of soldiers and commanders everywhere.)

“I don’t trust it,” Paris said to Ilion as he stared over the pattern-maps and their mystifying gaps. He almost knocked over a tall glass of wine.

Ilion deftly caught the glass. “You need to quit pruning your need for sleep,” she said. “If it’s regenerating this fast, you need the rest more than we need you awake obsessing over the invaders’ whimsies.”

“You’re taking this too lightly.”

Ilion fixed him with an interested stare. “Excuse me,” she said, “somebody is forgetting who’s responsible for coordinating all the systems around here. Even when I’m busy feeding you grapes because you’ve forgotten to show up for dinner again.”

Paris gave it up. He didn’t like the fact that none of their intelligence had anticipated this development. They had spent long hours tracing through what they knew of the invaders’ councils—depressingly little, in spite of their studies of signal traffic, and repeated attempts to crack the encryption—in an attempt to decipher its significance. So far they had a lot of speculation and little evidence to back up any of the going hypotheses.

“Stop that,” Ilion said.

Paris realized he had been tapping his foot in a querulous one-two, one-two-three, one-two rhythm. “Sorry,” he said, mostly sincerely.

“Look,” Ilion said, leaning over him. She was tall now, even allowing for the fact that he was slouched in his chair. “If there’s a pattern in there, any shred of meaning or menace, I’ll find it. The young are so”—she smoothed his hair back and kissed the side of his brow—“impatient. We will prevail.”

“Other than the kiss,” Paris said, unimpressed, “you’re starting to sound like my brother. You’re more succinct, though.”

Ilion laughed. “He does like his rallying speeches, doesn’t he? It’s a harmless foible, as these things go.” Her hands trailed lower, began massaging the knots in Paris’s neck. The calluses on her fingers were oddly soothing.

“I would feel so much better if you showed any sign of concern,” Paris said.

“No, you wouldn’t,” she returned, and he couldn’t refute her. But she smiled at him, dangerously. In the light-dark of her eyes he saw the enormous edifices of calculation, systems and subsystems dedicated to analyzing the anomaly in the enemy’s behavior.

As it turned out, he shouldn’t have been reassured after all—not because she wasn’t devoted to the problem, but because she was.

Everyone in Ilion with a shred of understanding of strategic analysis dedicated a certain amount of their cognitive allocation to the problem of the vanished ships and whether they had, say, gone for reinforcements, or were skulking around doing something even worse, whatever that might be. (The sole exception was Cassandra; even Ilion gave up on coaxing her into joining the effort.) As a result, the enemy general’s mimetic attack, inscribed in the notation of negative space, penetrated the city-fort’s every level, from Ilion’s highest heuristics to the sub-sentient routines that ran the simplest defense grids. And at the appointed time, all of Ilion’s gates flowered open at once.

Even Paris, with his interest in matters mathematical, had been acculturated by the long siege to think of attack in terms of triremes and trebuchets, mass drivers and missiles. When he woke (having fallen asleep, without meaning to, while looking up a theorem concerning network topology), it took him a muddled hour to figure out what was going on.

By then it was too late.

Paris didn’t recognize the conquering general until she deigned to visit him. He was the last, although he would never know that. She dispensed of the rest of the royal family by fire and sword and bullet, by her annihilating brilliance.

“So you’re the cause of all this trouble,” the general said. She was made of articulated metal, shining in the gray light of the prison. Each time she moved, she made a metal-scrape whisper of bells.

Her voice was familiar and unfamiliar. Nevertheless, he was certain he had never heard it before. His bonds of gravity-weave at least permitted him to raise his head enough to look her in the eye.

The face, now—he knew that face. Once, through a scatter-veil of possibilities, he had seen it, golden-fair and blessed by goddesses three, beautiful in the way of bone and bullets and polished coins.

“I am Helen,” the general said, “and you’ve wasted ten years of everyone’s lives by sparking off a general war. Congratulations.”

Paris laughed painfully, contemplating her. “Damn,” he said. “The fairest isn’t a goddess after all, or a city, even. It’s a general with a slide rule for a heart. That’s a compliment, by the way.”

“You idiot,” Helen said. “You know as well as I do that the gods eavesdrop on everything. I can’t spare you now.”

“Sometimes it’s worth it just to say the truth as you see it,” Paris said.

“It’s over,” she said. “Your city will be dismantled into its constituent quarks, and no more people will have to die for its sake. Until the next fruit’s sprouting, anyway; there’s always some gardener of human dissent. But that’s a problem for the next general.”

“I should have chosen you,” Paris said. In that moment he fell in love the way you fell into a singularity, a moment spun into forever lingering.

Helen’s masked face held no expression except Paris’s own, faintly reflected. “Still an idiot,” she said, and this time there was real pity in her voice. “I know your story. Do you think you were the only one offered a choice?”

He had no answer for her. Even so, when she brought the gun up to his head, he did not close his eyes. His last thought was that Ilion had never had a chance.

“Variations on an Apple” copyright © 2015 by Yoon Ha Lee

Art copyright © 2015 by Wesley Allsbrook