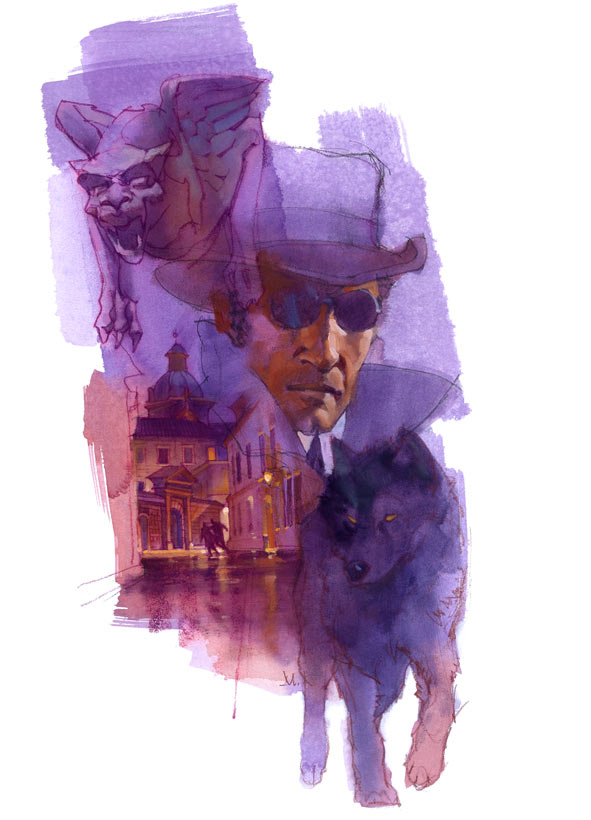

The Wizard has swallowed more and more of Europe–and inside his shuttered realm are magic and mass death. “The Pyramid of Krakow” is the sixth of Michael Swanwick’s “Mongolian Wizard” tales.

The man who got off the coach from Bern—never an easy trip but made doubly uncomfortable thanks to the rigors and delays of war—had a harsh and at first sight intimidating face. But once one took in his small black-glass spectacles and realized he was blind, pity bestowed upon him a softer cast. Until the coachman brought around his seeing-eye animal and it turned out to be a wolf.

The blind Swiss commercial agent took the wolf by the leash, placed a coin in the coachman’s hand, and then, accepting the leather tote containing toiletries, two changes of clothing, and not much else, strode into the cold and wintry streets of Krakow. On the rooftops, the gargoyles which the city tolerated because they kept down the rat population squinted and peered down at him, as if sensing something out of the ordinary. He did not, of course, look up at them.

Unassisted, the man made his way to a small hotel on Kanonicza Street, under the Royal Palace, where a modest room awaited him. There, after performing his ablutions, he got out his dip pen and a bottle of ink and composed a note on the hotel stationery:

Sir:

I have arrived in Krakow and await your pleasure.

Respectfully yours,

Hr. Mstz. Johann Fleischer

A modest bribe of a few copper coins sent the hotelier’s boy running out into the streets. Then Franz-Karl Ritter returned to his room to wait. Because the consequences of being discovered as an imposter and a spy were so dire, he did not take off his opaque glasses but remained in character. At a mental nudge, however, Freki put both paws on the sill of the lone window and stared intently into the smoky sky. Looking through his wolf’s eyes across the rooftops of the city, Ritter saw in the distance a cluster of smokestacks and, among them, the very top of a stepped pyramid.

There was an odd taint to the air but, try though they did, neither the wolf nor his master could identify it.

***

The next morning, by appointment, Ritter waited in the anteroom of an office whose appointments were of the finest, Freki lying by his feet, alert and patient.

A door opened and someone said, “Herr Fleischer.”

Ritter rose and, turning in the direction of the voice, said mildly, “Herr Meisterzauberer Fleischer, please. The title of archmage cost me years of my life and all of my vision, so I am afraid that I must insist upon its use.”

“Of course, Herr Meisterzauberer, of course. Józef Bannik, at your service. I am the Under Assistant Minister of Industry for the new government.”

“Ah, yes. The man who sent my superiors the remarkable request.”

“The very same. We shall talk in the carriage, assuming it is ready.” He raised his voice. “Kaśka! Have the preparations been made?”

A mousy brunette appeared in a side doorway, murmured, “All is as you required, Minister,” and withdrew, quietly closing the door behind her.

“My secretary,” Bannik said. “Quite efficient, considering. But not very personable. Well! Shall we go, then? To the carriage? I can offer you my arm if that would—”

“I will have no difficulty seeing my own way. That is what my animal is for.”

Outside, a carriage did indeed await them. Out of consideration for his host, Ritter took the center seat, so that Bannik would not have to sit next to his wolf. Freki studied the Under Assistant Minister of Industry with unblinking orange eyes. The man himself barked an order to the driver and the coach clattered off down the cobbled streets.

After some time it became obvious that Bannik was reluctant to resume their discussion, so Ritter said, “Your letter spoke of a pest problem, and also of a need for great quantities of a chemical for dealing with it. I presume you mean rat poison.”

Bannik cleared his throat. “Rat poison will not do. The animals we wish killed are considerably larger than that.”

“Farm animals? I should caution you that there are reasons why abattoirs do not employ chemicals. Reasons of safety for both the workers and, ultimately, the consumers of the meat.”

“Oh, no one will be eating the flesh of these animals—no, no, no,” the minister said with a chuckle so obviously false as to be alarming. “The very thought is laughable.”

Ritter responded to this sally with the smallest of noncommittal nods and once again an uncomfortable silence filled the cabin.

The carriage left the city and entered the countryside. When Ritter judged that enough time had passed for a master sorcerer to feel that he could utter such words without any loss of gravitas, he said, “I think I understand the sort of animal you mean. The kind that often troubles new governments.” Ritter could see nothing through his black eyeglasses of course. But looking through Freki’s eyes, he could see that Bannik was relieved not to have to put the thing into explicit words.

The minister tapped the side of his nose and winked. “I perceive that you are a man of the world. Yes, exactly so. Now, as to the qualities and quantities—”

Ritter held up a hand. “Before I could answer such questions, I would have to examine the facilities where the chemical is to be employed. In technical applications, context is all.”

“That is exactly what we are doing at this very moment. We are going to the site itself. The Great Pyramid,” Under Assistant Minister Bannik said, “of Krakow. In fact, we are arriving at the compound now.”

Indeed, the carriage was passing into what in Ritter’s experienced judgment must surely be an internment camp. Overhead floated a gateway with a banal and uplifting slogan spelled out in metal letters. Through the coach windows flooded an effluvium of misery and sickness, of excreta and vomit and pus, overlaid with coal smoke strongly flavored with the same unidentifiable smell that in lesser concentration permeated the air of Krakow. Only now, Ritter feared that the odor was not unidentifiable at all.

The carriage rattled by long rows of windowless barracks, triangular in cross section, each with a single padlocked door. “The pyramid is hollow, of course,” Bannik said, “supported by internal buttresses. We did not have decades in which to build it, as the ancient Egyptians did. Even then, tremendous amounts of labor were required but—ha! ha!—we do not lack for idle hands, do we?” He nodded at the barracks, acknowledging them for the first time.

The carriage lurched to a stop.

“Ah,” Bannik said. “We are here.”

***

Freki did not like climbing the pyramid. Nor, for that matter, did Ritter. Nothing was visible but lifeless stone, not even sky, so that it was as if the stairs led up a tremendous cliff face, and since the pyramid was new the air was raw with rock dust. Going up the steps was like ascending a mountain, but without the physical challenge or the mental exultation. All that remained was the drudgery and a wearying dread of what might be discovered at the top.

“This is the Way of Magisters and Acolytes,” Bannik commented.

“Eh?” Ritter said distractedly.

“The west face of the pyramid is reserved exclusively for officers and government officials—of which class you are an honorary member—and those brought up for special training. Inmates must ascend the east face. These steps remain unsullied.”

“Ah.”

There was a hypnotic quality to their ascent. The steady tedium of the climb, combined with the unvarying sameness of stone before him, soothed Ritter’s mind into a sort of dull quietude, as if he had stepped outside of his own body and were watching it from the outside, no longer fully invested in its welfare. He pictured a captive working upward on the other side, chained and shackled and guarded, falling into a similar bleak unthinkingness. He imagined it would be something of a blessing for the poor soul. Though naturally the pyramid’s designers would not have intended it as a mercy but rather as a means to promote docility.

Again Bannik spoke. “The acolytes’ ascent is made in ceremonial garments, to the accompaniment of music, the emotional and intellectual effect of which can well be imagined. Every possible detail has been carefully thought through.”

Ritter barely heard the man. The face of the pyramid lurched monotonously downward, one step following another. He found himself thinking back to when he was last in London.

***

“The Mongolian Wizard’s provisional government have made a fortress of Krakow,” Sir Toby had said. “It is what the Russians call a ‘closed city,’ where one requires official permission to enter or to leave. Nobody knows why—though of course there are many conflicting theories, all presented as solemn fact. Of them, the report you brought back from the Polish wizard is the most alarming.”

“It is nonsense,” Ritter said. “I say this as the man who was captured, tortured, and almost driven mad in the course of retrieving that report and consequently would prefer to believe that all my suffering was to some purpose. But it was not. Our source was deluded, or else an agent of the Polish underground feeding us misinformation in order to promote our enthusiasm for the liberation of his country. There is no third possibility.”

Sir Toby looked, as he so often did, pained. “It must be wonderful to live inside so certain a place as that thick skull of yours. Tell me, exactly what facts did you base your conclusion upon?”

“Surely the absurdity of the charges is self-evident. We are talking about Europe, after all, not some benighted heathen continent. Necromancy and human sacrifice! Those are exactly the sorts of slanders a nation levels against its enemy as propaganda. We may be at war, but we are still civilized peoples—and that includes the Russians. I’ve known several officers of the deposed tsar’s army and they were literate fellows with excellent manners who would never involve themselves in such actions.”

“Oh, Ritter. One would think that I would not have to lecture an officer in the Werewolf Corps on what evils men are capable of.” Sir Toby began lifting stacks of documents from his desk and depositing them atop other stacks, knocking an ashtray to the floor in the process. “Wherever did I put . . . ? Ah!” He produced a leather portfolio and then slapped down upon it three books, two fat and one lean, from his shelves. “Here is your documentation and a biography of the man you will be pretending to be. Two of the books cover the basics of chemistry and the third is A. G. Alchimie’s industrial catalog for chemicals in bulk. Memorize as much as you can and make sure you can bluff your way through the rest. You leave for the continent in the morning.”

Ritter eyed the books with distaste. “I was never very good at natural philosophy in school.”

“Well, now you’re being given a second chance. A great deal of bother and expense went into putting together your cover identity, so it is important that you determine as much as you can by the evidence of your own senses. Hearsay will not suffice. Also, I would appreciate it if you refrained from squandering our efforts by getting yourself killed.”

“I am certain,” Ritter said, “that I will not be confronted with anything I cannot handle.”

***

Neither Ritter nor Bannik spoke on the way down the pyramid. Ritter was silent in part because that was how his assumed character would behave, but mostly because he could not trust himself to speak. Bannik had his own reasons, apparently, which was fortunate for him. Ritter prided himself on his iron control; nevertheless, had the Under Assistant Minister said a word, he would surely have strangled the man.

Their carriage passed the barracks and then the tall chimneys of the crematoria at the edge of the camp. The smell of charred human flesh was almost unbearable there and, though it lessened as they passed through the countryside and back into town, it never quite dwindled to nothing. Freki, sensitive to his master’s mood, whined unhappily. Ritter laid a hand on the wolf’s back but did not touch his mind. By slow degrees, his resolve was returning. He had seen what he had come to see; now all that mattered was that he reported it to his superiors.

***

The bulk of the provisional government’s offices were, naturally, in the Royal Palace. However, the Ministry of Industry occupied overspill rooms in the Collegium Maius, the oldest building in the newly-closed university and one where, centuries before, the archmage Copernicus had been a student. The carriage pulled up in the courtyard and, once they had gotten by the plentiful and suspicious guards, Bannik led them back to his suite.

In the hallway, a young man rushed forward. “Herr Minister! I have a letter of commendation from—”

“Yes, yes,” Bannik said with a weary wave. “Czesław, isn’t it? I know your father. Take your letter to the mailroom and one of our fine lads will deliver it to Kaśka, who will know what to do with it.”

“But I—”

Bannik shut the door in the petitioner’s face. “The scion of a noble family,” he explained. “He wants to be a magician—a pyromancer, no doubt, or a levitator—but despite his lineage he has not the slightest talent for it. He thinks we can make a turnip out of a stone.” He continued into his office and sat down behind his desk. “Like so many of the young today, he’ll believe in any sort of rubbish.”

“He is not the only one,” Ritter said harshly.

Bannik raised an eyebrow. “Oh? You do not approve of what you saw atop the Great Pyramid? You think, perhaps, that we are returning to the Dark Ages?”

“I am a man of science,” Ritter said, because that was what his character would have said. “What I saw has no possible practical purpose whatsoever. None!”

“On the contrary, it is the very source of the empire’s power.” A small, moist smile blossomed on the Under Assistant Minister’s lips. “I see I have your attention.” He rang a small silver bell, and his secretary appeared. “Tea, Kaśka, if you please. For two.” Returning to his narration, he said, “It is not for nothing that our leader”—he meant the Mongolian Wizard—“is known as the Great Alienist. In his native land, there are no hereditary bloodlines of magicians as there are here, you see. Individuals with potential are taken under the care of shamans specially trained to the task and, through a combination of drugs and tantric techniques, have their talents opened for them. The process is slow and difficult, however. Our leader discovered that if trained alienists entered into the mind of an acolyte at the same time that it experienced great trauma—and now you know why the executions were so brutal—they could break the entrenched thought-habits of a lifetime, and impose new structures upon the brain. If one has the potential to be a magician, then the combination of a few atrocities and skilled mental surgery will in short order do the job.”

“It . . . seems impossible.”

“It is why our empire has so many more magicians than the decadent European nations. And why, ultimately, nobody is capable of standing against the Mongolian Wizard.” Bannik patted Ritter’s hand. “It was hard on all of us the first time. But one grows used to it.”

There were voices in the anteroom, all but inaudible through the heavy wooden door. They ceased and, shortly after, Kaśka reentered with the tea service on a silver tray.

“Who was that in the front office?” Bannik asked.

“A self-important nobody who wanted to see you. I sent him away with a flea in his ear.” Kaśka poured a cup of tea and presented it to Ritter. “Sugar? Milk?” When Ritter shook his head, she prepared a cup for Bannik, stirring in extra milk and sugar. He took a sip.

“Let’s get back to the topic of chemicals.” Bannik put down his cup in its saucer and said no more.

“Yes?”

The man did not speak. Nor did he move.

“Herr Bannik?”

“He’s dead,” Kaśka said. “And you are in terrible danger, Kapitänleutnant Franz-Karl Ritter.”

“Who are you?” Ritter asked.

“Someone who does not love the Mongolian Wizard. The man I sent away was a Hexenjäger—a witch finder—and he was looking for you. I told him you had gone back to your hotel. My deceit will not buy us much time.” Slamming open file cabinets, she swiftly assembled a thick bundle of papers. “These will document what you have seen.” There were heavy drapes before the window and a medieval hanging on one wall. Kaśka opened her superior’s desk, removed a box of matches, and set fire to both, as well as to a fringed sofa and a stack of papers she dropped onto the carpet. “And this should provide us with some distraction.”

“Give me the matches,” Ritter said. Kaśka looked at him curiously, but did as he said. They stepped out into the hall, closing the door firmly behind them.

As Ritter had expected, the fool outside hurried forward the instant they emerged. “Miss Kaśka, you must speak to the minister for me. From earliest childhood it has been my dream to be a magic-worker—”

“Then this is your lucky day,” Ritter said without stopping, “for I am the Director of Recruitment and Training of a new program that will transform you from a nobody into somebody useful to our cause.” Elated, the young man fell into step alongside him. “We are in need of fresh blood, and I believe you will do quite nicely.”

“Sir, I am . . . that is, thank you! You cannot imagine how much this means to me. I will do everything possible to justify your faith in me. I . . . Do I smell smoke?”

“You do not,” Ritter said, and saw Czesław automatically nod in agreement. The lad was as eager as a puppy and twice as guileless. He reminded Ritter of his younger self: idealistic, ambitious, and so eager to embrace his future that he’d swallow any lie, however transparent, that promised to get him there.

Now, however, there were shouts, and clerks began peering out of doorways and abandoning their offices. As they approached the main doors, Ritter could see the guards calmly ushering people out. As he’d feared, even as ministers and their underlings trotted down the halls toward freedom and somebody began hammering on the fire gong outside, they had kept their heads and were stopping and questioning all those carrying portfolios or papers.

Ritter slid his mind inside Freki’s and then tucked away his black-glass spectacles in a pocket. “Hold this,” he said, thrusting the box of matches at the startled Czesław.

Then he launched the wolf, snarling and snapping, directly at the young man’s crotch.

Understandably enough, Czesław ran from the animal, terrified, and was thus driven out the front door, matches in hand.

“Stop that man!” Ritter bellowed, simultaneously calling Freki to heel. “He is the arsonist!”

Smoke darkened the air and fleeing functionaries shoved past Ritter and Kaśka as they stepped briskly but without panic into the open and down the street. Behind them, the guards converged upon the hapless Czesław and began beating him senseless.

***

Ritter and the secretary had not gone far when Kaśka murmured, “We have been spotted. Whatever you do, don’t look.”

Ritter did not look. But Freki paused to sniff at an interesting doorstep and in doing so glanced back the way they had come. Through his eyes, Ritter saw a stocky man in a black cloak, a civilian, who stood with his back to the burning Collegium, staring intently after them.

Ritter said a bad word. “I thought I’d lost him in Switzerland.” Then he stumbled and almost fell as a spear of pain pierced his skull.

“A Hexenjäger cannot be lost, once he’s gotten a taste of your mind. Why are you grimacing so?”

“My head . . .”

Kaśka’s expression would have terrified a basilisk. “Idiot. I told you not to look. Can your wolf fend for himself?”

“Freki has experience passing as a stray.”

“Then send him away. Can you follow my lead or must I carry you?”

Ritter was a Teuton, an officer, and of noble blood to boot. He forced himself to hold his head high. “Pain is of no significance to me.”

“Very well. We are going to walk briskly and take many twists and turns. So long as he thinks we are trying to evade him, the witch finder will be in no hurry to catch us. Like any other hunter, he will conserve his strength while we expend ours. I have no allies I dare call upon within the city. He, meanwhile, is on home territory and very sure of himself. All his focus will be on disabling you. So we may confidently expect him to underestimate me.”

“You have a talent?” Ritter said with sudden hope.

Kaśka yanked him into a dank alleyway. “Of course not. My total lack of magic is my greatest asset.”

Through a maze of medieval streets they fled, over walls, through archways, down stone steps. Ritter was a lover of both cities and antiquities; under other circumstances he would have very much enjoyed this impromptu tour of the old town of Krakow. But the witch finder had his mental claws in Ritter’s brain, and the pain steadily increased until he could only see straight before himself through a narrowing tunnel of blackness.

Kaśka seized Ritter’s hand and tugged him onward. “Through this door,” she said. “Up these stairs.” Ritter stumbled up three flights and down a long hallway. Keys rattled. Through the fog of pain, he saw that Kaśka was unlocking the door to a small, low-roofed room. “My home,” she said, “such as it is.” Then, with grim humor, “When my landlady learns I’ve had a man up, there will be hell to pay.”

The room held a dresser with a pitcher and washbasin atop it, a wooden chair, and a narrow bed covered with a quilted white comforter. There was a single window, extending from knee-height almost to the ceiling. Ritter realized that this entire section of the floor was an afterthought, and had once been the upmost third of a much grander space.

Ritter moved yearningly toward the chair but Kaśka shoved him onto the bed instead. His body crashed down on it, making the rope supports under its mattress tick groan. He struggled to rise but could not.

“A garret is a terrible place to hide,” Ritter said weakly. Unseen hands of steel clasped his head and squeezed it so hard that he could no longer feel anything below his neck.

“Not in Krakow.” Kaśka went to the window and threw it open. There was a heavy barred grille behind it which she unlocked and, with a grunt of effort, flung wide. Ice-cold air gushed in.

With tremendous effort, Ritter managed to sit up. “What are you doing?”

“Lie back down, you fool! Lie down and don’t move a muscle. Are you incapable of following a woman’s instructions?”

“Kaśka,” Ritter said. “There is no sense in us both being caught. You can still escape.”

“First of all, my name is Katarzyna Skarbek,” the woman said with some asperity. “Kaśka is a baby name, a diminutive. Bannik employed it because he was a pig and I put up with it because I was working undercover. These conditions no longer apply. So I will appreciate your never using it again.”

“As you wish, Miss Skarbek. I was going to say . . .”

“Secondly, your survival is the entire point. You should not even be here. The resistance went through a great deal to compile a report and pass it on to your Willoughby-Quirke. Did he even receive it?”

“It was received but not believed.”

“Gods! I should—hark! The witch finder is coming up the stairs.”

Swiftly, Skarbek made sure the door was slightly ajar. Then she went to the window and stood facing outward, listening and waiting.

There were footsteps in the hall outside. They stopped. The door was cautiously pushed open. A stocky man in black appeared in the doorway, pistol in hand. He gave Ritter a cursory glance, then looked toward the window. His eyes widened.

The secretary had one foot on the sill and was about to climb out onto the roof.

Slamming the door behind him, the witch finder crossed the room in three strides. He seized Skarbek by the shoulder and flung her back within. She collided with the dresser, sending the pitcher and washbasin clattering. Then he stood, back to the window, training the gun on her and blocking her only avenue to escape.

A small smile of satisfaction played on the man’s face.

Then it disappeared.

Two stone hands closed about his throat. Then, so fast that he didn’t even have time to scream, he was hauled backwards through the window. Skarbek scrambled to her feet. She slammed shut the metal grate, locked it, and threw down the window.

Blood spattered the glass.

Ritter’s head was clearing now. He shook it and straightened. He looked out the window and saw three gargoyles fighting over the witch finder’s body, tearing open his flesh with talons and beaks. It took only an instant to be sure that the witch finder was dead. Then Ritter turned his back on the distressing scene. “That was an amazing piece of luck,” he observed at last.

“Luck had nothing to do with it,” Skarbek said. “Every day, for months, I have been saving bits of my lunch and dinner and throwing them out on the roof for the gargoyles. The creatures come flocking at the sound of the grate rattling open.”

* * *

It was evening when Ritter arrived in London, so he kenneled Freki and went to report to Sir Toby at his club. The hall porter at Boodle’s led him to a private sitting room where a fire had been lit and two glasses of cognac had been set out on a small table between green leather armchairs. Sitting staring into the hearth and holding the untasted drink cupped in both hands, Ritter thought back to Krakow and marveled that a single world could contain such disparities of condition.

After a time, he saw the second glass rise up from the table. Consequently, he realized that the glass was held by a man sitting in the chair opposite him and that the man was none other than Sir Toby.

Ritter laughed ruefully. “I’d almost forgotten you could do that.”

“Entering rooms unseen is a small talent, but mine own,” Sir Toby said. “It was mere vanity that made me employ it now.” Then, all business, “What do you have for me?”

Ritter relinquished the documents he had brought halfway across Europe and, as his superior perused them, narrated all that he had done and seen. The fire, meanwhile, burned low.

When the report was made, Sir Toby said, “You realize that the young man you denounced as an arsonist was doubtless sent to the same camp you visited, and then killed.”

“I am not proud of what I did,” Ritter said. “But neither do I feel guilty. There were children among those I saw slaughtered atop that damned pyramid.”

“Of course.”

“I do not feel guilty, I tell you!”

“Ritter, I am neither your father nor your priest-confessor. Indeed, it is too often my job to convince you of the necessity of such acts.” Sir Toby slapped his jacket pockets, produced a cigar case, and flipped back the top. “Smoke?”

Wordlessly, Ritter accepted the gift and then a light from his superior. The two puffed in silence for a time. Finally, Sir Toby sighed, evened up the papers, and tied them up in a bundle. “I will have these copied and distributed to the proper officials but . . .”

“But?”

“I believe you, Ritter. But will anybody else?”

As coldly as he could manage, Ritter said, “Then all that I have seen counts for nothing? All the sacrifices that the Resistance made to bring you evidence, the men that had to be killed to get me out of Krakow alive, Miss Skarbek’s being driven into hiding, were just so much lost effort?”

Sir Toby removed the cigar from his mouth and considered it thoughtfully. “You mustn’t think that, Ritter. In all confidence, you have made my job much easier. These past months I have been struggling with myself. There were certain actions which I hesitated to put into effect, some on moral grounds, others because they were simply so very dangerous. But now that I know the nature of what we are fighting, I can only conclude that I could do nothing worse than to let the Mongolian Wizard win this war. I think it is safe to say that absolutely anything is justified. Don’t you agree?”

There was a serene expression on Sir Toby’s face. It was that of a man who had been fighting the darker angels of his nature for a very long time and was at long last given license to set them free.

“The Pyramid of Krakow” copyright © 2015 by Michael Swanwick

Art copyright © 2015 by Gregory Manchess