A missing eye. A broken wing. A stolen country… The last job didn’t end well.

Years go by, and scars fade, but memories only fester. For the animals of the Captain’s company, survival has meant keeping a low profile, building a new life, and trying to forget the war they lost. But now the Captain’s whiskers are twitching at the idea of evening the score.

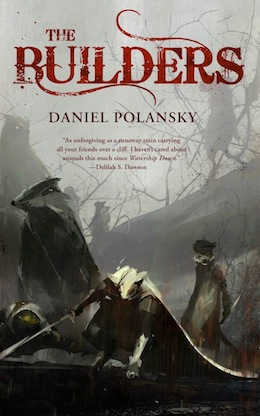

We’re pleased to present an excerpt from Daniel Polansky’s upcoming novella, The Builders—available in paperback, ebook, and audio format November 3rd from Tor.com!

1

A Mouse Walks into a Bar…

Reconquista was cleaning the counter with his good hand when the double doors swung open. He squinted his eye at the light, the stub of his tail curling around his peg leg. “We’re closed.”

Its shadow loomed impossibly large from the threshold, tumbling over the loose warped wood of the floorboards, swallowing battered tables and splintered chairs within its inky bulk.

“You hear me? I said we’re closed,” Reconquista repeated, this time with a quiver that couldn’t be mistaken for anything else.

The outline pulled its hat off and blew a fine layer of grime off the felt. Then it set it back on its head and stepped inside.

Reconquista’s expression shifted, fear of the unknown replaced with fear of the known quite well. “Captain…I… I didn’t recognize you.”

Penumbra shrunk to the genuine article, it seemed absurd to think the newcomer had inspired such terror. The Captain was big for a mouse, but then being big for a mouse is more or less a contradiction in terms, so there’s not much to take there. The bottom of his trench coat trailed against the laces of his boots, and the broad brim of his hat swallowed the narrow angles of his face. Absurd indeed. Almost laughable.

Almost—but not quite. Maybe it was the ragged scar which ran down half his face and through the blinded pulp of his right eye. Maybe it was the grim scowl set on his lips, a scowl that didn’t shift a hair as the Captain moved deeper into the tavern. The Captain was a mouse, sure as stone; from his silvery-white fur to his bright pink nose, from the fan-ears folded back against his head to the tiny paws he held tight against his sides. But rodent or raptor, mouse or wolf, the Captain was not a creature at whom to laugh.

He paused in front of Reconquista. For a moment one had the impression the ice which held his features in place was about to melt, or at least unsettle. A false impression. The faintest suggestion of greeting offered, the Captain walked to a table in the back, dropped himself lightly into one of the seats.

Reconquista had been a rat, once. The left side of his body still was, a firm if aging specimen of Rattus norvegicus. But the right half was an ungainly assortment of leather, wood and cast iron, a jury-rigged contraption mimicking his lost flesh. In general it did a poor job, but then he wasn’t full up with competing options.

“I’m the first?” the Captain asked, a high soprano though none would have said so to his face.

“Si, si,” said Reconquista, stutter-stepping on his peg-leg out from behind the bar. On the hook attached to the stump of his right arm was slung an earthenware jug, labeled with an ominous trio of x’s. He set it down in front of the Captain with a thud. “You’re the first.”

The Captain popped the cork and tilted the liquor down into his throat.

“Will the rest come?” Reconquista asked.

A half-second passed while the Captain filled his stomach with liquid fire. Then he set the growler back on the table and wiped his snout. “They’ll be here.”

Reconquista nodded and headed back to the bar to make ready. The Captain was never wrong. More would be coming.

2

A Stoat and a Frenchman

Bonsoir was a stoat, that’s the first thing that needs to be said. There are many animals that are like stoats, similar enough in purpose and design as to confuse the amateur naturalist—weasels, for instance, and ferrets. But Bonsoir was a stoat, and as far as he was concerned a stoat was as distinct from its cousins as the sun is the moon. To mistake him for a weasel, or, heaven’s forbid, a polecat—well, let’s just say creatures that voiced that misimpression tended not to do so ever again. Creatures who voiced that misimpression tended, generally speaking, not to do anything ever again.

Now a stoat is a cruel animal, perhaps the cruelest in the gardens. They are brought up to be cruel, they must be cruel, for nature, who is crueler, has dictated that their prey be children and the unborn, the beloved and the weak. And to that end nature has given them paws stealthy and swift, wide eyes to see clear on a moonless night, a soul utterly remorseless, without conscience or scruple. But that is nature’s fault, and not the stoat; the stoat is what it has been made to be, as are all of us.

So Bonsoir was a stoat, but Bonsoir was not only a stoat. He was not even, perhaps, primarily a stoat. Bonsoir was also a Frenchman.

A Frenchman, as any Frenchman will tell you, is a difficult condition to abide, as much a privilege as a responsibility. To maintain the appropriate standards of excellence, this SUPERLATIVE of grace, was a burden not so light even in the homeland, and immeasurably more difficult in the colonies. Being both French and a stoat had resulted in a more or less constant crisis of self-identity—one which Bonsoir often worked to resolve, in classic Gallic fashion, via monologue.

And indeed, when the Captain entered the bar he was expounding on his favorite subject to a captive audience. He had one hand draped around a big-bottomed squirrel resting on his knee, and with the other he pawed absently at the cards lying face-down on the table in front of him. “Sometimes, creatures in their ignorance have called me an ermine.” His pointed nose trailed back and forth, the rest of his head following in train. “Do I look like an albino to you?”

There were five seats at the poker table but only three were filled, the height of Bonsoir’s chip stack making clear what had reduced the count. The two remaining players, a pair of bleak, hard looking rats, seemed less than enthralled by Bonsoir’s lecture. They shifted aimlessly in their seats and shot each other angry looks, and they checked and rechecked their cards, as if hoping to find something different. They might have been brothers, or sisters, or friends, or hated enemies. Rats tend to look alike, so it’s tough to tell.

“Now a stoat,” Bonsoir continued, whispering the words into the ear of his mistress, “a stoat is black, black all over, black down to the tip of his…” he goosed the squirrel and she gave a little chuckle, “feet.”

The Swollen Waters was a dive bar, ugly even for the ugly section of an ugly town, but busy enough despite this, or perhaps because of it. The pack of thugs, misanthropes and hooligans that thronged the place took a good hard look at the Captain as he entered, searching for signs of easy prey. Seeing none they fell back into their cups.

A swift summer storm had matted down the Captain’s fur, and to reach a seat at the bar required an ungainly half-leap. Between the two he was more than usually perturbed, and he was usually quite perturbed.

“You want anything?” The server was a shrewish sort of shrew, as shrews tend to be.

“Whiskey.”

A miserly dram poured into a stained glass. “We don’t get many mice in here.”

“We’re not partial to the stench of piss.” The captain said curtly, throwing back the shot and turning to watch the tables.

Back at the table the river card had been laid, and Bonsoir’s lady-friend rested on the vacant seat next to him. One rat was already out, the stack of chips on the table too much weight for his wallet to support. But the other had stayed in, calling Bonsoir’s raise with the remainder of his dwindling finances. Now he triumphantly tossed his cards down on the table and reached for the pot.

“That is a very fine hand,” Bonsoir said, and somehow when he had finished this statement his paw was settled atop the rat’s, firmly keeping him from withdrawing his winnings. “That is the sort of hand a fellow might expect to get rich off.” Bonsoir flipped his own over, revealing a pair of minor nobles. “Such a fellow would be disappointed.”

The rat looked hard at the two thin pieces of paper which had just lost him his savings. Then he looked back up at the stoat. “You’ve been taking an awful lot of pots tonight.” His partner slid back from the table and rested his hand on a cap-and-ball pistol in his belt. “An awful lot of pots.”

Bonsoir’s eyes were cheery and vicious. “That is because you are a very bad poker player,” he said, a toothy smile spreading across his snout, “and because I am Bonsoir.”

The second rat double-tapped the butt of his weapon with a curved yellow nail, tic tic, reminding his partner of the play. Around them the other customers did what they could to prepare for the coming violence. Some shifted to the corners. Those within range of an exit chose this opportunity to slip out of it. The bartender ducked beneath the counter and considered sadly how long it would take to get the bloodstains out of his floor.

But after a moment the first rat blinked slowly, then shook his head at the second.

“That is what I like about your country,” Bonsoir said, merging his new winnings with his old. “Everyone is so reasonable.”

The story was that Bonsoir had come over with the Foreign Legion and never left. There were lots of stories about Bonsoir. Some of them were probably even true.

The rats at least seemed to think so. They slunk out the front entrance faster than dignity would technically allow—but then rats, as befits a species subsisting on filth, make no fetish of decorum.

The Captain let himself down from his high chair and made his way to the back table, now occupied solely by Bonsoir and his female companion. She had resumed her privileged position on his lap, and chuckled gaily at the soft things he whispered into her ear.

“Cap-i-ton,” Bonsoir offered by way of greeting, though he had noted the mouse when first he entered. “It has been a long time.”

The Captain nodded.

“This is a social call? You have tracked down your old friend Bonsoir to see how he has accommodated to his new life?”

The Captain shook his head.

“No?” The stoat set his paramour aside a second time and feigned wide-eyed surprise. “I am shocked. Do you mean to say you have some ulterior motive in coming to see Bonsoir?”

“We’re taking another run at it.”

“We are taking another run at it?” Bonsoir repeated, scratching at his chin with one ebony claw. “Who is we?”

“The gang.”

“Those who are still alive, you mean?”

The Captain didn’t answer.

“And why do you think I would want to be rejoin the…gang, as you say?”

“There’ll be money on the back end.”

Bonsoir waived his hand over the stack of chips in front of him. “There is always money.”

“And some action. I imagine things get dull for you, out here in the sticks.”

Bonsoir’s shivered with annoyance. So far as Bonsoir was concerned, whatever space he occupied was the center of the world. “Do I look like Elf to you, so desperate to kill? Besides—there are always creatures willing to test Bonsoir.”

“And of such caliber.”

Bonsoir’s upper lip curled back to reveal the white of a canine. “I am not sure I understand your meaning, my Cap-i-ton.”

“No?” The Captain pulled a cigar out of his pocket. It was short, thick and stinky. He lit a match against the rough wood of the chair in front of him and held it to the end. “I think you’ve grown fat as your playmate. I think wine and females have ruined you. I think you’re happy here, intimidating the locals and playing lord. I think this was a waste of my time.”

The Captain was halfway to the door when he felt the press of metal against his throat. “I am Bonsoir,” the stoat hissed, a scant inch from the Captain’s ears. “I have cracked rattlesnake eggs while their mother slept soundly atop them, I have snatched the woodpecker mid-flight. More have met their end at my hand then of corn liquor and poisoned bait! I am Bonsoir, whose steps fall without sound, whose knives are always sharp, who comes at night and leaves widows weeping in the morning.”

The Captain showed no signs of excitement at his predicament, or surprise at the speed and quiet with which Bonsoir had managed to cross the distance between them. Instead he puffed out a dank blend of cigar smoke and continued casually. “So you’re in?”

Bonsoir scooted frontside, his temper again rising to the surface. “Do you think this is enough for Bonsoir? This shithole of a bar, These fools who let me take there money? Do you think Bonsoir would turn his back on the Cap-i-ton, on his comrades, on the cause!” The stoat grew furious at the suggestion, working himself into a chittering frenzy. “Bonsoir’s hand is the Cap-i-ton’s! Bonsoir’s heart is the Cap-i-ton’s! Let any creature who thinks otherwise say so now, that Bonsoir may satisfy the stain on his honor!”

Bonsoir twirled the knife in his palm and looked around to see if anyone would take up the challenge. None did. After a moment the Captain leaned in close and whispered, “St. Martin’s day. At the Partisan’s bar.”

Bonsoir’s knife disappeared somewhere about his person. His hand rose to the brim of his beret and chopped off a crisp salute, the first he had offered anyone in half a decade. “Bonsoir will be there.”

3

Bonsoir’s Arrival

Bonsoir made a loud entrance for a quiet creature. The Captain had been sitting silently for half an hour when the double doors flew open and the stoat came sauntering in. It was too fast to be called saunter, really, Bonsoir bobbing and weaving to his own internal sense of rhythm—but it conveyed the same intent. A beret sat jauntily on his scalp, and a long black cigarette dangled from his lips. Strung over his shoulder was a faded green canvas sack. He carried no visible weapons, though somehow this did not detract from his sense of menace.

He nodded brusquely to Reconquista and slipped his way to the back, stopping in front of the main table. “Where is everyone?”

“They’re coming.”

Bonsoir took his beret off his head and scowled, then replaced it. “It is not right for Bonsoir to be the first—he is too special. His arrival deserves an audience.”

The Captain nodded sympathetically, or as close as he was capable with a face formed of granite. He passed Bonsoir the now half-empty jug as the stoat bounced against a stool. “They’re coming,” he repeated.

4

The Virtues of Silence

Boudica lay half buried in the creek bed when she noticed a figure threading its way along the the dusty path leading up from town. The stream had been dry for years now, but the shifting silt at the bottom was still the coolest spot for miles, shaded as it was by the branches of a scrub tree. Most days, and all the hot ones, you could find Boudica there, whiling away the hours in mild contemplation, a hunk of chaw to keep her company.

When the figure was half a mile out, Boudica’s eyebrows elevated a tick above their resting position. For the opossum, it was an extraordinary expression of shock. Indeed, it verged on hysteria. She reflected for a moment longer, than resettled her bulk into the sand.

This would mean trouble, and generally speaking, Boudica did not like trouble. Boudica, in fact, liked the absolute opposite of trouble. She liked peace and quiet, solitude and silence. Boudica lived for those occasional moments of perfect tranquility, when all noise and motion faded away to nothing, and time itself seemed to still.

That she sometimes broke that silence with the retort of a rifle was, in her mind, ancillary to the main issue. And indeed, it was not her steady hands that had made Boudica the greatest sniper who had ever sighted down a target. Nor her eyes, eyes that had picked out the Captain long moments before anyone else could have even made him for a mouse. It was that she understood how to wait, to empty herself of everything in anticipation of that one perfect moment—and then to fill that moment with death.

As an expert then, Boudica had no trouble abiding the time it took the mouse to arrive, spent it wondering how the Captain had found her. Not her spot at the creek bed; the locals were a friendly bunch, would have seen no harm in passing on that information. But the town itself was south of the old boundaries, indeed as south as one could go, surrounded by an impenetrably barren wasteland.

Boudica spat a jet of tobacco juice into the weeds and set her curiosity aside. The Captain was the sort of creature who accomplished the things he set out to do.

Finally the mouse crested the little hill that led up to Boudica’s perch. The Captain reacted to the sight of his old comrade with the same lack of excitement that the opossum had displayed upon picking him out some twenty minutes prior. Though the heat was scorching, and the walk from town rugged, and the Captain no longer a pinky, he remained unwinded. As if to fix this, he reached into his duster and pulled out a cigar, lit it and set it to his mouth. “Boudica”

Boudica swatted away a fly that had landed on the top of her exposed tummy. “Captain,” she offered, taking her time with each syllable, as she did with everything.

“Keeping cool?”

“Always.”

It was a rare conversation where the Captain was the more active party. He disliked the role, though it was one he had anticipated playing when enlisting the opossum. “You busy?”

“Do I look it?”

“Up for some work?”

Boudica rose slowly from the dust of the creek bed. She brushed a layer of sand off her fur. “Hell, Captain,” the savage grin contrasting unpleasantly with the dreamy quietude of her eyes, “what took you so long?”

5

Boudica’s Arrival

When the Captain returned from the back Boudica was at the table, the brim of her sombrero covering most of her face. Leaning against the wall behind her was a rifle nearly as long as its owner, black walnut stock with an intricately engraved barrel. She was smiling quietly at some jest of Bonsoir’s as if she had been there all day, indeed, as if they had never parted.

He thought about saying something, but decided against it.

6

The Dragon’s Lair

The Captain had been journeying for the better part of three days when he crested the woodland path into the clearing. He was in the north country, where there was still water, and trees, and green growing things—but even so it was a dry day, and the heat of the late afternoon held its grip against the coming of the evening. He was tired, and thirsty, and angry. Only the first two were remediable, or the result of his long walk.

Inside the clearing sat a squat, stone, two-story structure with a thatched roof and a low wall surrounding it. In front of the entrance was a whittled sign which read ‘Evergreen Rest’. Inside a thin innkeeper waited to greet him, and a fat wife cooked stew, and a homely daughter set the tables.

The Captain did not go inside. The Captain swung round to the small garden which lay behind the building.

In recent years these sorts of hostelries had become less and less common, with bandits and petty marauders plaguing the roads, choking traffic and making travel impossible for anyone unable to afford an armed escort. Even the lodges themselves had become targets, and those that remained had begun to resemble small forts, with high walls, and stout doors, and proprietors that greeted potential customers with cocked scatterguns.

The reason the Evergreen Rest had undergone no such revisions—the reason no desperado within five leagues was foolish enough to buy a glass of beer there, let alone make trouble—stood behind an old tree stump, an ax poised above his head. Age had withered his skin from a bright crimson to a deep maroon, but it had done nothing to excise the flecks of gold speckled through his flesh. Apart from the shift in hue the years showed little on the salamander. He balanced comfortably on webbed feet, sleek muscle undiluted with blubber. His faded trousers were worn but neatly cared for. He had sweated through his white shirt, and loosened his shoestring necktie to ease the passage of his breath.

He paused at the Captain’s approach, but went back to his work after a moment, splitting logs into kindling with sure, sharp motions. The Captain watched him dismember a choice selection of timber before speaking. “Hello, Cinnabar.”

Cinnabar had calm eyes, friendly eyes, eyes that smiled and called you ‘sir’ or ‘madam’, depending on the case, eyes like cool water on a hot day. Cinnabar had hands that made corpses, lots of corpses, walls and stacks of them. Cinnabar’s eyes never seemed to feel anything about what his hands did.

“Hello, Captain.” Cinnabar’s mouth said. Cinnabar’s eyes said nothing. Cinnabar’s arms went back to chopping wood.

“It’s been a while,” the Captain added, as if he had just realized it.

“Time does that.”

“Time does.” The Captain agreed. “You surprised to see me?”

Cinnabar took another log from the pile, set it onto the tree stump. “Not really,” the denial punctuated by the fall of his ax.

The Captain nodded. It was not going well, he recognized, but wasn’t quite sure why or how to change it. He took his hat off his head and fanned himself for a moment before continuing. “You a cook?” and while waiting for the answer he reached down and picked up a small rock.

“Busboy.”

“It’s been a long walk. Think I could get some water?”

Cinnabar stared at the Captain for a moment, as if searching for some deeper meaning. Then he nodded and started toward a rain barrel near the back entrance. As he did so the Captain, with a sudden display of speed, pitched the stone he had been holding at the back of his old companion’s head.

For a stuttered second it sailed silently toward Cinnabar’s skull. Then it was neatly cradled in the salamander’s palm. But the motion which ought to have linked these two events—the causal bridge between them—was entirely absent, like frames cut from a film.

“That was childish.” Cinnabar said, dropping the stone.

“I needed to see if you still had it.”

Cinnabar stared at the Captain with his eyes which looked kind but were not.

“You know why I’m here?

“Are you still so angry?”

The Captain’s drew himself up to his full height. It wasn’t much of a height, but that was how high the Captain drew himself. “Yeah,” he muttered. “Hell yeah.”

Cinnabar turned his face back to the unchopped pile of wood. He didn’t say anything.

Gradually the Captain deflated, his rage spent. “So you’ll come?”

Cinnabar blinked once, slowly. “Yes.”

The Captain nodded. The sound of someone laughing drifted out from the inn. The crickets took to chirruping. The two old friends stood silently in the fading light, though you wouldn’t have know it to look at them. That they were old friends, I mean. Anyone could see it was getting dark.

Excerpted from The Builders © Daniel Polansky, 2015