The villagers in the sleepy hamlet of Lychford are divided. A supermarket wants to build a major branch on their border. Some welcome the employment opportunities, while some object to the modernization of the local environment.

Judith Mawson (local crank) knows the truth—that Lychford lies on the boundary between two worlds, and that the destruction of the border will open wide the gateways to malevolent beings beyond imagination. But if she is to have her voice heard, she’s going to need the assistance of some unlikely allies…

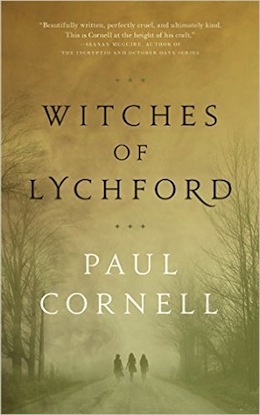

We’re pleased to present an excerpt from Paul Cornell’s Witches of Lychford, publishing in paperback and ebook September 8th from Tor.com!

1

Judith Mawson was seventy-one years old, and she knew what people said about her: that she was bitter about nothing in particular, angry all the time, that the old cow only ever listened when she wanted to. She didn’t give a damn. She had a list of what she didn’t like, and almost everything—and everybody—in Lychford was on it. She didn’t like the dark, which was why she bit the bullet on her energy bills and kept the upstairs lights on at home all night.

Well, that was one of the reasons.

She didn’t like the cold, but couldn’t afford to do the same with the heating, so she walked outside a lot. Again, that was only one of the reasons. At this moment, as she trudged through the dark streets of the little Cotswolds market town, heading home from the quiz and curry night at the town hall at which she had been, as always, a team of one, her hands buried in the pockets of her inappropriate silver anorak, she was muttering under her breath about how she’d get an earful from Arthur for being more than ten minutes late, about how her foot had started hurting again for no reason.

The words gave her the illusion of company as she pushed herself along on her walking stick, past the light and laughter of the two remaining pubs on the Market Place, to begin the slow trudge uphill on the street of charity shops, towards her home in the Rookeries.

She missed the normal businesses: the butcher and the greengrocer and the baker. She’d known people who’d tried to open shops here in the last ten years. They’d had that hopeful smell about them, the one that invited punishment. She hadn’t cared enough about any of them to warn them. She was never sure about calling anyone a friend.

None of the businesses had lasted six months. That was the way in all the small towns these days. Judith hated nostalgia. It was just the waiting room for death. She of all people needed reasons to keep going. However, in the last few years she’d started to feel things really were getting worse.

With the endless recession, “austerity” as those wankers called it, a darkness had set in. The new estates built to the north—the Backs, they had come to be called—were needed, people had to live somewhere, but she’d been amazed at the hatred they’d inspired, the way people in the post office queue talked about them, as if Lychford had suddenly become an urban wasteland. The telemarketers who called her up now seemed either desperate or resigned to the point of a mindless drone, until Judith, who had time on her hands and ice in her heart, engaged them in dark conversations that always got her removed from their lists.

The charity shops she was passing were doing a roaring trade, people who’d otherwise have to pay to give things away, people who couldn’t otherwise afford toys for their children. Outside, despite the signs warning people not to do so, were dumped unwanted bags of whatever the owners had previously assumed would increase in value. In Judith’s day . . . Oh. She had a “day” now. She had just, through dwelling on the shite of modern life, taken her seat in the waiting room for death. She spat on the ground and swore under her breath.

There was, of course, the same poster in every single window along this street: “Stop the Superstore.”

Judith wanted real shops in Lychford again. She didn’t like Sovo—the company that had moved their superstores into so many small towns—not because of bloody “tradition,” but because big business always won. Sovo had failed in its initial bid to build a store, and was now enthusiastically pursuing an appeal, and the town was tearing itself apart over it, another fight over money.

“Fuss,” Judith said to herself now. “Fuss fuss bollocking fuss. Bloody vote against that.”

Which was when the streetlight above her went out.

She made a little sound in the back of her throat, the closest this old body did to fight or flight, halted for a few moments to sniff the air, then, not sure what she was noting, carefully resumed her walk.

The next light went out too.

Then, slightly ahead of her, the next.

She stopped again, in an island of darkness. She looked over her shoulder, hoping someone would come out of the Bell, or open a door to put their recycling out. Nobody. Just the sounds of tellies in houses. She turned back to the dark and addressed it.

“What are you, then?”

The silence continued, but now it had a mocking quality. She raised her stick.

“Don’t you muck about with me. If you think you’re hard enough, you come and have a go.”

Something came at her out of the darkness. She sliced the flint on the bottom of her stick across the pavement and made a sharp exclamation at the same instant.

The thing hit the line and enough of it got past to bellow something hot and insulting into her face, and then it was gone, evaporated back into the air.

She had to lean on the wall, panting. Whatever that had been had almost got past her defences.

She sniffed again, looking around, as the street lights came back on above her. What had it been, to leave a smell of bonfire night? A probe, a poke, nothing more, but how could even that be? They were protected here. Weren’t they?

She looked down at a sharper smell of burning, and realised that had been a closer run thing than she’d thought: the line she’d scratched on the pavement was burning.

Judith scuffed it over with her boot—so the many who remained in blissful ignorance wouldn’t see it—and continued on her way home, but now her hobble was faster and had in it a sense of worried purpose.

* * *

It was bright summer daytime, and Lizzie was walking by the side of the road with Joe. They were messing around, pretending to have a fight. They had decided on something they might one day fight about and they were rehearsing it like young animals, she knocking him with her hips, him flapping his arms to show how useless he’d be. She wanted him so much. Early days, all that wanting. He looked so young and strong, and happy. He brought the happy, he made her happy, all the time. A car raced past, horn tooting at them, get a room! She feinted at his flailing, ducked away, eyes closed as one of his fingers brushed her cheek. She shoved out with both hands and caught him on the chest, and he fell back, still laughing, into the path of the speeding car.

She opened her eyes at the screech and saw his head bounce off the bonnet and then again on the road. Too hard. Much too hard.

She woke slowly, not suddenly with a gasp like in the movies. She woke slowly and took on slowly, as always, the weight of having dreamed about him. She recognised her surroundings, and she couldn’t help but look over to what, until just over a year ago, had been his side of the bed. Now it was flat, and there were still pillows, pristine, and he still wasn’t there.

She found the space in her head where she prayed and she did that and there was nothing there to answer, as there hadn’t been for a while now, but after a minute or so she was able—as always—to get up and begin her day.

Today there was a parochial church council meeting. In Lychford, judging from the three she’d been to so far, these always involved whizzing through the agenda and then having a lengthy, intricate debate about something near enough to the bottom of it to make her think that this time they’d get away early. Before this afternoon’s meeting she had a home communion visit with Mr. Parks, who’d she’d been called to administer the last rites to last week, only to find him sitting outside his room at the nursing home, chatting away and having tea. It had been a bit hard to explain her presence. Vicars: we’re not just there for the nasty things in life. Before that, this morning, she was due to take the midweek Book of Common Prayer service. She looked at herself in the mirror as she put on her crucifix necklace and slipped the white strip of plastic under her collar to complete the uniform: the Reverend Lizzie Blackmore, in her first post as new vicar of St. Martin’s church, Lychford. Bereaved. Back home.

The Book of Common Prayer service was, as usual, provided for three elderly people with a fondness for it and enough clout in the church community to prevent any attempt to reschedule their routine. She’d known them all years ago when she was a young member of the congregation here.

“I wouldn’t say we’re waiting for them to die,” Sue, one of the churchwardens, had said, “oh, sorry, I mean I can’t. Not out loud, anyway. “ Lizzie had come to understand that Sue’s mission in life was to say the things that she, or indeed anyone else, wouldn’t or couldn’t. Just as well Lizzie did little services like this one on her own, except for the one elderly parishioner out of the three whose turn it was to read the lessons, boomingly and haltingly at the same time, hand out the three prayer books and collect the nonexistent collection.

When Lizzie had finished the service, trying as always not to interject a note of incredulity into “Lord . . . save the Queen,” she had the usual conversations about mortality expressed through concern about the weather, and persuaded the old chap who was slowly collecting the three prayer books that she’d do that today, really, and leaned on the church door when it closed behind them and she was alone again.

She would not despair. She had to keep going. She had to find some reason to keep going. Coming home to Lychford had seemed like such a good idea, but . . .

From the door behind her there came a knock. Lizzie let out a long breath, preparing herself to be the reverend once again for one of the three parishioners who’d left her glasses behind, but then a familiar voice called through the door. “Lizzie? Err, vicar? Reverend?” The voice sounded like it didn’t know what any of those words meant, her name included. Which was how it had always sounded since it and its owner had come back into Lizzie’s life a week ago. Despite that, though, the sound of the voice made Lizzie’s heart leap. She quickly restrained that emotion. Remember what happened last time.

She unlatched the door, and by the time she swung it back she had made herself seem calm again. Standing there was a woman her own age in a long purple dress and a woollen shawl, her hair bound with everything from gift ribbons to elastic bands. She was looking startled, staring at Lizzie. It took Lizzie a moment to realise why. Lizzie raised her hand in front of her clerical collar, and Autumn Blunstone’s gaze snapped up to her face. “Oh. Sorry.”

“My eyes are up here.”

“Sorry, only that’s the first time I’ve seen you in your . . . dog . . . no, being respectful now—”

“My clerical collar?”

“Right. That. Yes. You . . . okay, you said to come to see you—”

Lizzie had never thought she actually would. “Well, I meant at the vicarage . . .”

“Oh, yes, of course, the vicarage. You don’t actually live here at the church. Of course not.”

Lizzie made herself smile, though none of her facial muscles felt up for it. “Come on in, I won’t be a sec.” She made to go back to the office to put in the safe the cloth bag that didn’t have a collection in it, but then she realised Autumn wasn’t following. She looked back to see the woman who’d used to be her closest friend poised on the threshold, unwilling to enter.

Autumn smiled that awful awkward smile again. “I’ll wait here.”

* * *

They’d lost touch, or rather Autumn had stopped returning her calls and emails, about five years ago, just after Lizzie had been accepted into theological college, before Lizzie had met Joe. That sudden cessation of communication was something Lizzie had been astonished by, had made futile efforts to get to the bottom of, to the extent of showing up on Autumn’s doorstep during the holidays, only to find nobody answering the door. She’d slowly come to understand it as a deliberate breaking of contact.

It made sense. Autumn had always been the rational one, the atheist debunker of all superstition and belief, the down-to-earth goddess who didn’t believe in anything she couldn’t touch. The weight of being judged by her had settled on Lizzie’s shoulders, had made thoughts of her old friend bitter. So, on coming back to Lychford to take up what, when she’d come here to worship as a teenager, had been her dream job, she hadn’t searched for Autumn, had avoided the part of town where her family had lived, even. She had not let thoughts of her enter her head too much. Perhaps she would hear something, at some point, about how she was doing. That had been what she’d told herself, anyway.

Then, one Friday morning, when she’d been wearing civvies, she’d seen a colourful dress across the Market Place, had found the breath caught in her throat, and had been unable to stop herself from doing anything except marching over there, her stride getting faster and faster. She’d hugged Autumn before she knew who it was, just as she was turning, which in Lizzie’s ideal and desired world should have been enough to begin again with everything, but then she had felt Autumn stiffen.

Autumn had looked at her, as Lizzie had let go and stepped back, not as a stranger, but as someone Autumn had expected to see, someone she’d been worrying about seeing. Lizzie had felt the wound of Joe open again. She’d wanted to turn and run, but there are things a vicar cannot do. So she’d stood there, her best positive and attentive look locked on her face. Autumn had quickly claimed a previous engagement and strode off. “Come to see me,” Lizzie had called helplessly after her.

Lizzie had asked around, and found that the guys down the Plough knew all about Autumn, though not about her connection to Lizzie, and had laughed that Lizzie was asking about her, for reasons Lizzie hadn’t understood. She’d looked for Autumn’s name online and found no contact details in Lychford or any of the surrounding villages.

Now, Lizzie locked up, and went back, her positive and attentive expression again summoned, to find Autumn still on the threshold. “So,” Lizzie said, “do you want to go get a coffee?” She kept her tone light, professional.

“Well,” said Autumn, “Reverend . . . I want to explain, and I think the easiest way to do that is if you come to see my shop.”

* * *

Autumn led Lizzie to the street off the Market Place that led down to the bridge and the river walk, where the alternative therapy establishments and the bridal shop were. Lizzie asked what sort of shop Autumn had set up. She was sure she’d already know if there was a bookstore left in town. Autumn just smiled awkwardly again. She halted in front of a shop Lizzie had noted when she first got here and stopped to look in the window of. Autumn gestured upwards at the signage, a look on her face that was half “ta daa!” and half kind of confrontational. Witches, the sign said in silver, flowing letters that Lizzie now recognised as being in Autumn’s handwriting, The Magic Shop.

“You . . . run a magic shop?” said Lizzie, so incredulous that she wondered if the gesture might mean something else, such as “Oh, look at this magic shop, so against everything I’ve ever espoused.”

“Right,” said Autumn. “So.”

“So . . . ?”

“So I’m sure this isn’t the sort of thing you’d want to associate yourself with now that you’re a reverend.”

Lizzie didn’t know if she wanted to hug Autumn or slap her. Which was a pretty nostalgic feeling in itself. “If this is the new you,” she said, “I want to see it. I’m happy to step over your threshold.”

Autumn gave her a look that said “yeah, right” and unlocked the door.

* * *

Inside, Lizzie was pleased to find herself in a space that said her old friend, scepticism apart, didn’t seem to have changed all that much. The displays of crystals, books about ritual and healing, posters and self-help CDs were arranged not haphazardly, but in a way which said there was a system at work here, just one that would make any supermarket customer feel they’d been slapped around by experts. Crystal balls, for example, which Lizzie thought would be something people might want to touch, rolled precariously in plastic trays on a high shelf. Was there an association of magic shop retailers who might send a representative to tut at the aisle of unicorn ornaments, their horns forming a gauntlet of pointy accidents waiting to happen? She was sure that, as had been the case with every room or car Autumn had ever been in charge of, she would have a reason why everything was as it was.

Autumn pulled out a chair from behind the cash desk for Lizzie, flipped over the sign on the door so it said “Open” again, and marched into a back room, from where Lizzie could hear wineglasses being put under the tap. At noon. That was also a sign Autumn hadn’t changed.

“You can say if you’re not okay with it,” she called.

“I’m okay with it,” Lizzie called back, determinedly.

“No, seriously, you don’t have to be polite.” Autumn popped her head out of the doorway, holding up a bottle. “Rosé? Spot of lady petrol? Do you still do wine? I mean, apart from in church when it’s turned into—if you think it does turn into—”

“Do you have any tea?”

Autumn stopped, looking as if Lizzie had just denounced her as a sinner. “There’s an aisle of teas,” she said.

“Well, then,” Lizzie refused to be anything less than attentive and positive, “one of those would be nice.”

Autumn put down the bottle, and they went to awkwardly explore the aisle of teas, arranged, as far as Lizzie could see, in order of . . . genre? If teas had that? “So . . . this is . . . quite a change for you.”

Autumn halted, her hand on a box of something that advertised itself as offering relaxation in difficult circumstances. “Look who’s talking. You were Lizzie Blackmore, under Carl Jones, under the Ping-Pong table, school disco. And now you’re a . . . reverend, vicar, priest, rector, whatever.”

“But I always . . . believed.” She didn’t want to add that these days she wasn’t so sure.

“And I always thought you’d get over it.”

Lizzie nearly said something very rude out loud. She took a moment before she could reply. “Autumn, we are standing in your magic shop. And you’re still having a go at me for being a believer. How does that work? Are you, I don’t know, getting the punters to part with their cash and then laughing at them for being so gullible? That doesn’t sound like the Autumn I used to know.”

Autumn wasn’t looking at her. “It’s not like that.”

“So you do believe?”

“I’m still an atheist. It’s complicated.”

“You don’t get that with craft shops, do you? ‘Will this fitting hang up my picture?’ ‘It’s complicated.’”

“Don’t you dare take the piss. You don’t know—!”

Lizzie couldn’t help it. The sudden anger in Autumn’s voice had set off her own. “You dropped me when I went away. You dropped me like a stone.”

“That was complicated too. That was when things got . . . messed up.”

Lizzie felt the anger drain from her. One facet of Autumn’s character back in the day had been that she came to you when she needed something. She was always the one who knocked on your door in the middle of the night, sobbing. Had something bad happened to make her come to Lizzie’s door again today? “Did you stay in Lychford back then? Or did you go away too?”

“A bit of both.” A clenched grin.

“Where did you go?”

Autumn seemed to think about it. Then she shook her head. “I shouldn’t have come to see you. I’m sure you’re busy, Reverend, I’ve just got to . . .” She gestured towards the inner door. “You see yourself out.”

Lizzie desperately wanted to argue, but just then the shop bell rang, and a customer entered, and Autumn went immediately to engage with her. Lizzie looked at the time on her phone. She needed to go to see Mr. Parks. “If you need me, Autumn,” she called as she left, and it was on the verge of being a yell, “you let me know.”

* * *

The following evening, Judith decided to do something she had never deliberately done before. She was going to participate in the civic life of the town. Which meant that first she had to negotiate getting out of her house. She went to put the recycling out, having spent a relaxing five minutes crushing cans with her fingers, and found that her neighbour, Maureen Crewdson, was putting hers out too. Maureen had found herself running for mayor, unopposed, because nobody wanted to do it. “By accident,” she’d said, having one night had a few too many Malibus down the Plough. Of all the people Judith had to put up with, she was one of the least annoying. She had, tonight, the same weight about her shoulders that Judith had seen for the last few weeks. “I’m coming to the meeting tonight,” Judith told her, and watched as, imperceptibly, that weight increased.

“I didn’t think you’d be bothered with all that. Are you for or against the new shop?”

“I’ve decided I really don’t like it.” Since summat had had a go at scaring and then attacking her for considering voting against, that was.

The weight on Maureen’s shoulders increased again. “Oh. It’s going to bring so many jobs to . . . sod it, can we please not talk about it?”

There was some strangling emotion wrapped around her, something only Judith could sense, that would take a bit of effort to identify. Judith didn’t feel up for poking into her business that much at this point. She knew better than to go rummaging into private pain. Looks like it’s going to rain, dunt it?” Judith felt the relief as she left Maureen to it, and went back inside to make herself a cup of tea while considering her exit strategy. She waited until a few minutes before she had to go, then took a deep breath and called up the stairs. “I’m off to the meeting.” Silence. That was odd. What had happened to the noise from the telly? “Arthur? You hear what I said?”

This silence had something aware in it. Mentally girding her loins, Judith set off up the stairs.

* * *

Arthur was sitting where he always sat—in the bedroom, in his favourite chair, which he’d had her haul up here, the sound of his ventilator sighing and heaving. It was normally obscured by the constant noise of the telly, but the mute was on, and Arthur was fiddling with the remote, trying to get the sound back. He was watching some quiz show. That and ancient whodunits were all he watched, the older the better. Judith kept the Sky subscription going just for him. He didn’t acknowledge her arrival. “Arthur, I said—”

“I heard you, woman. You’re leaving me again.”

She didn’t let her reaction show. “It’s only for an hour, and your programme’s on in a minute.” Waking the Dead. He loved gory mortuary dramas. Of course he did. She took the remote off him and tried to find the button to unmute it, which was hard in this light.

He looked up at her with tears in his eyes. “You’ll be sending me away soon. Your own husband. You’ll be putting me where you don’t have to see me.”

“If only I could!”

His face contorted into a sly grin, his cheeks still shining. “Will your boyfriend be there tonight, full of Eastern promise? Oh, that accent, he’s so lovely, so mobile!”

She kept on trying to work out the remote, not looking at him. “You don’t know what you’re talking about, you old fool.”

“That’d make it easy to send me away, wouldn’t it, if I was going mental? You reckon he can make you feel young again? You’re planning to get rid of me!”

“I bloody can’t, though, can I?” Judith threw the remote at somewhere near him, turned on her heel and marched out of the door, only for her conscience to catch up with her, along with his howls of laughter, on the first step of the stairs. With an angry noise in her throat, she went back in, managed to switch the sound back on, slapped the remote back into his hands, and then left the cackling old sod to it. She put on her coat. As she got to the front door she heard his laughter turn to stage sobs, or real sobs, but still she made herself get outside and close the door without slamming it behind her.

Excerpted from Witches of Lychford © Paul Cornell, 2015