I owe the readers of my Craft Sequence a brief apology.

When I wrote Three Parts Dead, I knew it was one piece of a larger mosaic—that while the characters I’d introduced were awesome, I wanted to tell the story of a larger world across many times and cultures. The epic fantasy tradition’s usual approach to this sort of challenge is to send Our Heroes on a road trip that would put Sal Paradise to shame, ping-ponging around a killer, super-detailed map with stops in every port roughly proportional to that port’s political or geomantic influence. Or the number of Pokemon you can catch in the neighboring forest, or whatever.

(Sidebar: You know those crazy population- or GDP-based projections of the world map, where the world is funhouse mirrored to make space proportional to a chosen metric? How cool would it be to see a version of that for, say, Randland or Fionavar based on page count? I guess if you wanted to do Fionavar you’d have to include an insert for Toronto. Anyway.)

The On the Road approach to epic fantasy is great, and I love that kind of book, but I wasn’t sure it was the right path for what I had in mind. For example, it takes a long time for a person to learn a new culture to the point where her statements about it transcend gross generalization. What country, friends, is this? It’s Illyria, the captain says, and now Viola’s out to solve the mystery of Illyria. Who lives here, what are they like? She meets three lovesick fools, and concludes that the people of Illyria are lovesick fools—this is the kind of logic that causes people returning from a three day trip to Thailand to say things like “The Thai people are so (protip—it doesn’t matter what word or phrase you put here, they’re all cringeworthy).” So I wanted to write about groups of people embedded in communities, which meant either a single enormous plot that could affect people all over the world (thereby maybe rendering irrelevant the same cities and cultures I wanted to explore—there may be eight million stories in the naked city, but when Godzilla’s in town the only stories that matter star him, or her depending on your feelings about the 1999 Godzilla), or a bunch of different plots that formed a larger image when seen from a distance.

(From a distance, the world looks blue and green….)

Mosaics operate in at least two dimensions; the paint-chip variety use the horizontal and vertical, while I wanted to use time and space, skipping from setting to setting and year to year to chart the growth and transformation of organizations over decades. “But books have maps to help people figure out where everything is, Max,” interjected my subconscious at this point. “And it’s hard to track timelines! You love Bujold and you still can’t quite figure out where Cetaganda fits in the Miles books without reference to Wikipedia. You should help people orient themselves in time so they can figure out where events stand in causal relationship to one another, who’s dead, who’s alive, and suchlike. Because Kant.”

Once I got done hitting my subconscious with a golf club for the Kant reference, I took a shower, which is something writers do after they’ve beaten people with golf clubs. So I’m told.

“What if,” said my subconscious, which was still there because ideas turn out to be golf-club-proof as well as bulletproof, “you actually included the temporal order of the books in their titles? Publication order is easy to check, so you don’t need to worry about telling people where a given book falls in that; sliding the number into the title will let readers know where the books fall causally. Also, it frees you of the need to work in direct temporal order. You can ratchet back and forth along the number line, describe effects before causes, and do all sorts of fun structural stuff. If you wanted, you could explore the God Wars one book, bounce forward a decade in the next, and then return to the ‘present.’ Easy-peasy.”

Dear reader, never trust anyone who uses phrases like ‘easy-peasy,’ especially if they’re your subconscious.

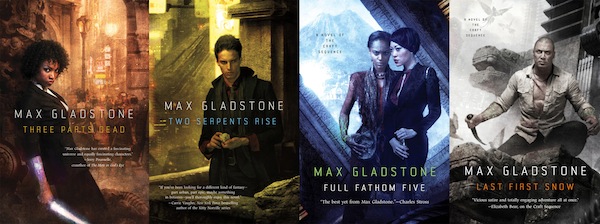

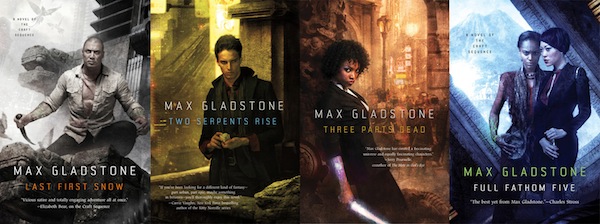

But that was (and remains) the idea: to reduce readers’ reliance on timelines, and give myself more of a challenge when coming up with titles, since titles aren’t hard enough already. While Three Parts Dead was first in publication order, it falls sort of in the middle of the timeline of books I’ve written thus far. Two Serpents Rise, despite containing none of the same characters (though the King in Red is referenced once in Three Parts Dead—blink and you’ll miss it), is set a couple years earlier. Full Fathom Five, which comes out this July, takes place a couple years after Three Parts Dead, while Last First Snow, the fourth book, is about twenty years before Two Serpents Rise, and… well, that’s before I even break into imaginary and irrationals! Though I’m not sure whether my editors will let me get away with i, Necromancer, or e Parts Dead.

So maybe it wasn’t that brief an apology after all. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I need to go clean my metaphorical golf clubs.

Max Gladstone writes books about the cutthroat world of international necromancy: wizards in pinstriped suits and gods with shareholders’ committees. You can follow him on Twitter.