In “Advanced Readings in D&D,” Tor.com writers Tim Callahan and Mordicai Knode take a look at Gary Gygax’s favorite authors and reread one per week, in an effort to explore the origins of Dungeons and Dragons and see which of these sometimes-famous, sometimes-obscure authors are worth rereading today. Sometimes the posts will be conversations, while other times they will be solo reflections, but one thing is guaranteed: Appendix N will be written about, along with dungeons, and maybe dragons, and probably wizards, and sometimes robots, and, if you’re up for it, even more.

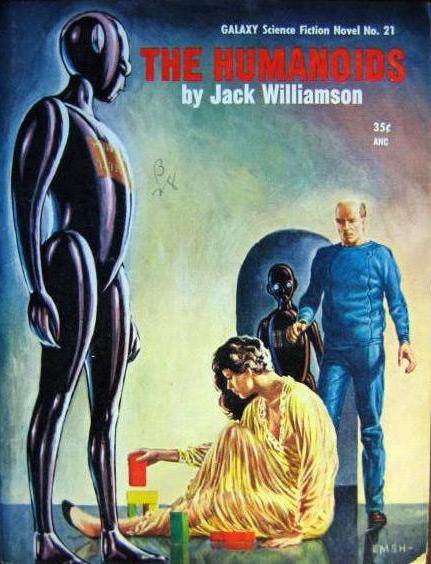

Welcome to the fourteenth post in the series, featuring a look at The Humanoids by Jack Williamson.

Tim Callahan: Well here’s a sci-fi novel in a classic mold. And yet another author I hadn’t read before. Jack Williamson apparently started his career by mashing up The Three Musketeers with Falstaff in the distant future and launching the crew as The Legion of Space. If you start your writing career that way, I will pay attention to you. (Or, I will once I find out that’s how you started your writing career, anyway.) But we didn’t choose The Legion of Space for our Williamson selection. We chose The Humanoids. I don’t remember why—it was probably one of the first books that popped up under his name when I started looking around for Jack Williamson reading material. But The Humanoids is pretty good—unsettling, ambitious, and maybe a bit messy in the end—and though it suffers from some of the sterility of prose that many Golden Age of Sci-Fi novels suffer from, I found it compulsively readable. It has a paranoid cinematic quality to it. Like a Twilight Zone episode blown out to feature-length and blasted onto the big screen.

Unfortunately, the version of The Humanoids I read also contains the 1947 Jack Williamson short story “With Folded Hands,” which is a thematic precursor to The Humanoids and—this is where the problem comes in—it reads like a really good, tightly-focused, panicked episode of The Twilight Zone, so it makes Williamson’s follow-up in The Humanoids seem bloated and digressive in comparison.

I still enjoyed The Humanoids, but I wonder how I would have felt about it if I didn’t begin by reading “With Folded Hands.” Did you read that Williamson story, or did you just jump right into The Humanoids novel itself?

Mordicai Knode: Honestly I just started and I decided to skip right to The Humanoids. I am so far…well, I’d honestly forgotten that we’d picked it! I am in the middle of reading it, all “wait, so…what, Gary?” Honestly though, I think this goes to the point of what we were saying about Carnellian Cube, doesn’t it? Another “high concept” idea, which is the sort of thing that does successfully translate into an adventure or campaign. I will tell you what though; my overwhelming thought while I read through this is just that it reads like a really long, belabored, maybe paid-by-the-word episode of the Outer Limits or Twilight Zone. That, I think, is probably us being spoiled by living in the future! There wasn’t a Twilight Zone when The Humanoids was written, you know?

Alright, thanks to the miracle of “the way writing works,” I’ve finished! You know what, I actually really like the ending. That is a sort of voice that I imagine existing in a lot of science fiction; the “dissenting opinion.” You know, these days you really only get two straw men fighting over each other: consider Avatar, where you have the magical Dances With Wolves guy being like “no, we should be respectful of others and nature” versus a “no, racism is awesome and I love destroying the environment!” argument. Blah. As a sidebar, while watching Avatar I kept pretending that the Na’vi were actually Xenomorphs; it really made the Bad Military Haircut Guy’s opinions make a lot more sense. In a way, Humanoids is like that. It has layers; maybe the bad guys are right, no the bad guys are the worst, no maybe the bad guys are right, repeat until you reach the end.

TC: This novel does delve into the stuff of Philosophy 101, like those at-the-coffee-house post-seminar conversations where you debate what happiness is, and some guy is all like, “yeah, but what if you could achieve perfect happiness but the cost was being hooked up to a machine pumping happy juice into your brain and you could never leave that room? But you were totally happy, you know?”

That’s what The Humanoids essentially asks—only with robots and freedom fighters and a plot that isn’t as strong as its central conceit.

It really does suffer compared to “With Folded Hands,” which turns the concept into a slow unfolding of terror as the super-helpful, humanity-serving robots methodically force a kind of happy contentment on everyone. Told that way, it’s not really about a “dissenting opinion,” since there’s no one rooting for happiness at the expense of personal freedom in the short story, but Williamson does allow his characters to wrestle with their own issues about what it means to be human.

In The Humanoids they wrestle with that, and with the notion of liberty, and with the threat of the inhumanity of the machine (even if the machine will do what is in the best interest of humanity, coldly speaking).

It’s a classic sci-fi concept. It’s a classic literary concept. My son is in middle school and he’s just starting to get to the point where his English teacher will expect some kind of literary analysis (even if its relatively simplistic) as they read books, and I clued him in on the secret of literature: it’s almost always about the individual trying to break away from some kind of system. He laughed when I told him that and said, “I’m not a part of your system!” in reference to the Lonely Islands song “Threw it on the Ground.” But it’s true. That’s what that song’s about. That’s what The Humanoids is about. That’s what life’s about.

MK: That video cracks me up, the one for “Threw It On the Ground.” Good times. Anyhow, I’ve heard it said that there are two different dystopias that the world needs to worry about: the 1984 dystopia where you need to worry about things being taken away from you, and the Brave New World dystopia where you need to worry about things being given to you. Which is a fine moral to a story, an interesting observation that says a lot about, you know, consumerism and advertising or whatever—sure—I’m just unclear on how it relates to Dungeons and Dragons. I mean, you could have a whole campaign about golems or Inevitables or Modrons and co-opt the plot from this book, but I think that is a stretch.

Maybe the lesson you could learn from this book is that making hugely flawed characters is more interesting than making banal superhuman heroes who laugh in the face of danger and never give into the temptation to pry the ruby eyes out of the idol of Fraz-Urb’luu?

TC: Yeah, I don’t see the Dungeons and Dragons link at all, and I am pretty darn sure Gary Gygax didn’t have any Modrons in mind when he generated his list of fave books. The Modrons are wonderful and all—who doesn’t like Rubik the Amazing Cube mashed up with Mr. Spock—but they aren’t central to early D&D. Or any D&D. Ever.

But, to be fair, Appendix N doesn’t specifically name The Humanoids as an influence, but mentions Jack Williamson in general. Probably his pulpier early stuff was what Gygax had had in mind. In retrospect, we should have read the Legion of Musketeers in Space with Falstaff and Friends book. But something called The Humanoids sounds like D&D from a distance. If you squint. And don’t read the back of the book.

MK: Oh man, now I am sort of thinking about the parallel universe where we read Legion of Musketeers in Space with Falstaff and Friends because dang, that is a hell of a title. Still, we picked this up because it seemed like the most germane Williamson, and that says something about the state of pulps, fantasy, and science fiction at the time. People like Williamson were jumping between genre helter-skelter; is it any wonder so much of the early Dungeons and Dragons stuff was similarly all over the map, in terms of tone and material? Spaceships, cowboys, Alice in Wonderland, whatever! Everything was coming from a contextual smorgasbord.

TC: And yet Dungeons and Dragons, devouring that smorgasbord, ended up inspiring countless bland, sterile high-fantasy worlds. Somewhere along the way, everything just became codified into a too-familiar system of signs and signifiers. But we can’t blame Jack Williamson for that. He was warning us about the perils of…the machine!

Tim Callahan usually writes about comics and Mordicai Knode usually writes about games. They both play a lot of Dungeons & Dragons.